A rapid review informing an assessment tool to support the inclusion of lived experience researchers in disability research

Revue rapide d’un outil d’évaluation pour soutenir l’inclusion des scientifiques ayant une expérience vécue dans la recherche sur le handicap

Damian Mellifont, Ph.D.

Lived experience Postdoctoral Fellow

Centre for Disability Research and Policy, The University of Sydney

damian [dot] mellifont [at] sydney [dot] edu [dot] au

Abstract

Appreciating that progress is being made in terms of valuing researchers with lived experience in research about disability, far more efforts are nonetheless needed to redress ableism and to further advance inclusion. Addressing this policy issue, this rapid review aims to inform researchers with disability and their genuine allies about: a) scholarly discussions concerning the inclusion of researchers with lived experience of disability in lived experience led or co-produced disability research; and b) a practical disability research assessment tool to support this greater inclusion. The review was informed by thematic analysis as applied to 13 publications retrieved from a rapid review of ProQuest Central, Scopus, Education Source, Google Scholar and Google Chrome databases. An additional six publications were identified from peer suggestions and hand searches of citations. The three themes identified each inform about ways of including people with lived experience of disability in research about disability across respective areas of designing disability research, conducting disability research, and disseminating and evaluating disability research findings. This exploratory paper offers a preliminary, evidence-based assessment tool to help to include more researchers with lived experience of disability as leaders and co-producers of disability research.

Résumé

La valorisation des scientifiques ayant une expérience vécue au sein de la recherche sur le handicap a connu de bonnes avancées. Néanmoins, de nombreux efforts supplémentaires sont nécessaires pour remédier au capacitisme et faire progresser davantage l’inclusion. La présente revue rapide vise à aborder cet enjeu politique afin d’outiller les scientifiques handicapé·es et leurs véritables allié·es sur : a) les discussions académiques concernant l’inclusion de scientifiques ayant une expérience vécue du handicap dans la recherche menée ou coproduite sur le handicap; et b) un outil pratique d’évaluation de la recherche sur le handicap pour soutenir cette inclusion élargie. La revue s’est basée sur une analyse thématique appliquée à treize publications extraites d’un examen rapide des bases de données ProQuest Central, Scopus, Education Source, Google Scholar et Google Chrome. Six publications ont été ajoutées grâce à des suggestions de collègues et une recherche manuelle parmi les références bibliographiques. Les trois thèmes identifiés abordent les stratégies permettant d’inclure les personnes ayant une expérience vécue du handicap dans la recherche sur le handicap lors de la conception de la recherche sur le handicap, lors de la conduite de la recherche sur le handicap et lors de la diffusion et de l’évaluation des résultats de la recherche sur le handicap. Cet article exploratoire propose un outil d’évaluation préliminaire fondé sur des données probantes pour aider à inclure davantage de chercheur·ses ayant une expérience vécue du handicap en tant que leaders et coproducteur·trices de la recherche sur le handicap.

Keywords: Co-production; Disability; Employment; Ableism; Inclusion

Mots-cléss: Coproduction; handicap; emploi; capacitisme; inclusion

Introduction

Advocacy has traditionally played an important role in advancing inclusive disability research. In the early 1990s disability activists made strong calls for disability research to confront the isolation and social oppression as experienced by people with disability by embracing critical inquiry and changing relationships between research subjects and researchers (Barnes and Mercer 1997; Oliver, 1992). Within this inclusive approach to disability research, people with disability and their organisations hold greater control over the research process (Barnes & Sheldon, 2007). Inclusive disability research therefore involves the active participation of people with lived experience of disability in informing policies and practices as researchers (Centre for Disability Research and Policy, 2023). The literature has applied many terms in describing people with lived experience of disability who conduct disability research. These include service user researchers, research survivors, consumer researchers, lived experience academics, and Mad researchers (Sin et al., 2010; Landry, 2017; Sweeney, 2016; Byrne, 2014). According to LeFrancois et al. (2013), Mad Studies originated from Canada and involved people who were engaged in activist scholarship and who provided narratives as psychiatric survivors. Regardless of the language that is used to describe researchers with disability, their inclusion and power holdings in contemporary disability research remains as an important area of scholarly investigation. The meaning of researcher with disability that is to be consistently applied throughout this paper is a person with disability who leads or co-produces disability research and who may or may not hold professional research qualifications.

Arnstein’s ladder of participation has described processes at the lower rungs whereby traditional holders of power continue to maintain their control through to the highest rungs where citizens are empowered by their participation in decision making (Arnstein, 1969; Bovill & Bulley, 2011). While not offering a perfect reflection of reality, the model has nevertheless described power holdings across wide-ranging disciplines including those of housing, social care, health, and the environment (Bovill & Bulley, 2011). In terms of disability research, at the lowest rung, people with lived experience of disability are consulted about research design, with non-disabled researchers retaining voice and control, whereas at the highest rung, research is led by people with disability (Aboaja et al., 2021; Arnstein, 1971; Caton, 2020; Jennings et al., 2018). Involvement of people with disability in research about disability can thus range from that which is tokenistic all the way through to meaningful inclusion as highly valued research team members (Bowers et al., 2008; Simpson, 2013).

A number of benefits can flow from the inclusion of researchers with lived experience of disability in disability research. These advantages include the setting of research directions that hold relevance to disability communities, redressing an imbalance of power, promoting the voice of disability in the research agenda, as well as advancing the respectful inclusion of ideas that come more broadly from lived experiences with disability (Boydell et al., 2021; Fothergill et al., 2013; Liddiard et al., 2019; Olsen et al., 2016; Rose, 2015). Landry (2017) has also stressed the capacity of survivor researchers in Canada to address important policy areas including those of employment and housing. The inclusion of researchers with disability is fundamental to supporting the validity of the disability research (Smith & Bailey, 2010; Entwistle et al. 1998). There is also a growing recognition of the value of lived experience in terms of contributing to the generation of knowledge about mental health (Boydell et al., 2021). Such potential for lived experience informed disability research to create pragmatic and positive change in society should not be undervalued. In this context, it is recognised that researchers with lived experience of disability can target socially responsible topics and support the progression of ethical social transformations (Landry, 2017; Sweeney, 2016).

Arblaster (2020) has advised that lived experience informed work is about growing opportunities to draw upon personal experiences and comprehensions for the betterment of other people. Applications of lived experiences are recognised across diverse areas including those of policy, services and research (Sin et al., 2010). Faulkner (2017) has also noted an increase in the number of people with disability who are undertaking PhDs. Despite these positive developments, the strength of support for lived experience-led and co-produced research nevertheless remains open to debate. As the names suggest, lived experience-led research involves disability research that is led by people with disabilities, while co-produced research is conducted with people with disabilities who are often non-academic researchers (Voronka, 2016; Beckett et al. 2018; Darby, 2017). Boydell et al. (2021) have cautioned that lived experience research can be difficult to identify and access. There is also a lack of available funding that is needed to allow more disability research to be led by researchers who have lived experience of disability (Sweeney, 2016; Wykes, 2003). Consequently, Banas et al. (2019) have warned of an ongoing paucity of people with disability who are employed as researchers.

Researchers with lived experience of disability have equitable and legitimate roles in the disability research industry. People with disability need to speak on their own behalf about their lived experiences (Solis, 2006). Ableism (i.e., disability discrimination), however, can play a key role in dismissing the research careers of people with disability. As this ‘ism’ is driven by the belief that disability, including all types of disability, are automatically negative, people with disability can experience coercion and discrimination (Beresford, 2000; Campbell, 2009). Research production can therefore be alienating of people with disability in an academic community that is traditionally conservative (Oliver, 1992; Barnes, 2003). A bio-medically focused academy has treated people with disability as subjects of study with a long-delayed recognition of their rightful positions in research as lived experience experts (Milner & Frawley, 2018). Subsequent to this acknowledgment and aligning with the social model of disability has been an inclusive shift from ‘research on’ to relevant ‘research with’ individuals with disability (Barnes & Sheldon, 2007; Walmsley & Johnson, 2003; Oliver, 1992).

Appreciating the progress that has been made towards a greater inclusion of researchers with disability in disability research, their level of involvement still varies markedly. For example, Landry (2017) has cautioned that ‘research by’ research survivors in the United Kingdom have exceeded those that have been conducted in Canada. Helping to remove these kinds of inconsistencies, far more research efforts are needed to redress ableism and to advance lived experience led and co-produced research in an inclusive academy (Mellifont, 2019; 2019a). Following on, the aims of this rapid review are to inform researchers with disability and their genuine allies about: a) scholarly discussions concerning the inclusion of researchers with lived experience of disability in lived experience led or co-produced disability research; and b) a practical disability research assessment tool to support this greater inclusion.

Method

Rapid reviews are designed to swiftly address a research topic by purposefully constraining the volume of databases that are to be searched and narrowing the inclusion of papers (Harker et al., 2012). Khangura et al. (2012) has also advised that typically completed in five weeks or less, rapid reviews purposefully confine the data sources accessed and the searches applied. Recognising the exploratory nature of this rapid review, a streamlined approach was deemed suitable for expediently addressing the research aims as previously stated. Such streamlining is demonstrated with search terms deliberately confined to publications which specifically refer to ‘lived experience led’ or ‘co-produced’ disability research. Tricco, Langlois and Straus (2017) have also noted that approximately half of rapid reviews are undertaken by a single reviewer, with this approach described as reasonable where the review is conducted by an experienced researcher (as was the case for this exploratory study).

The two search terms as defined above were first applied to Google Scholar and Google Chrome databases. These data sources are appropriate for conducting rapid reviews as they are each described as having powerful search capacity (Deakin University, 2021). Additional scholarly database enquiries included those of Scopus, ProQuest Central and Education Source. These academic databases were purposefully chosen for their potential to inform the research aim. Publications were also identified through peer suggestions and hand searches of citations from included publications. Inclusion criteria consisted of: a) publication type = journal article, report, thesis, conference paper, submission, or book chapter; b) publication date = all years; and c) publication language = English. Exclusion criteria consisted of: a) publication does not inform about the inclusion of researchers with disability in lived experience led or co-produced disability research; or b) no full text is available.

The author exported references from the database searches into EndNote before being importing these into Covidence where duplicates were removed ready for single-reviewer screenings. The author then carried out title and abstract screenings followed by full text screenings. Next, a charting process was carried out to allow for the extraction of relevant information from each included document and included fields of: a) authors; b) publication year; c) publication type; and d) content relating to informing about the inclusion of researchers with lived experience of disability in lived experience led or co-produced disability research. Included references and their PDF files were then imported into NVivo and inductively assessed through the author’s application of thematic analysis. This qualitative analytical approach involved an iterative process of: a) searching for themes, b) naming themes and c) reviewing themes (Braun et al., 2006). Coding continued until a state of theoretical saturation was attained. Supporting research rigor and reliability, references supporting each theme were captured and clearly presented among the results.

Results

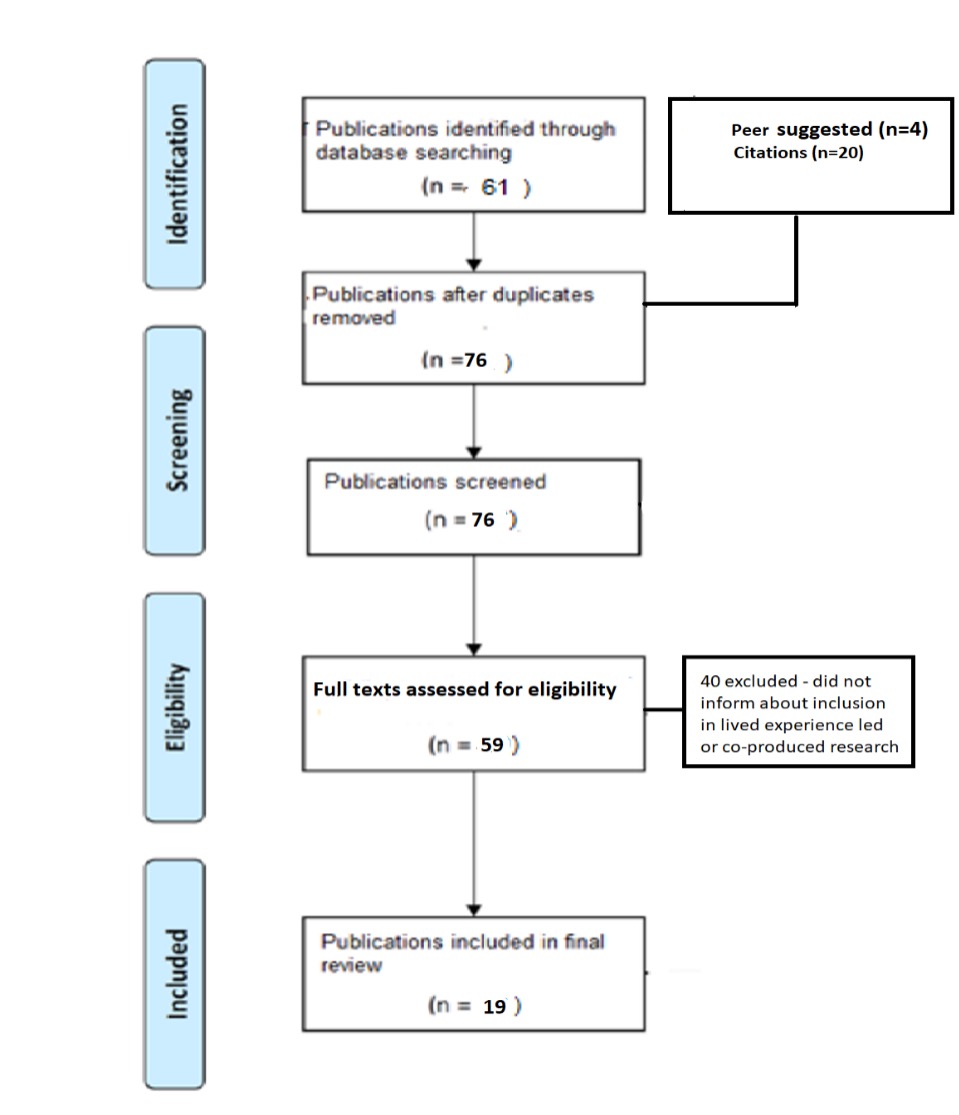

Reflecting the targeted nature of this rapid review, of the 76 possibly relevant documents derived from the searches of Scopus, ProQuest Central, Education Source, Google Scholar and Google Chrome databases as well as publications identified from peer suggestions and citations, 59 full texts were assessed for eligibility. Of these, a total of 19 publications were deemed to be relevant after applying the exclusion criteria (see Figure 1 PRISMA Statement). Table 1 depicts the results of the thematic analysis by recording themes and their associated supporting documents. The three themes identified each inform about ways of including people with lived experience of disability in research about disability across respective areas of: a) designing disability research; b) conducting disability research; and c) disseminating and evaluating disability research findings. Table 2 below describes the publications by publication type.

| Theme | Supporting documents |

|---|---|

| Including lived experience in the design of research about disability | Aboaja et al. (2021); Arblaster (2020); Aubrecht et al. (2021); Boydell et al. (2021); Buettgen et al. (2020); Burghardt et al. (2023); Byrne et al. (2019); Byrne (2014); Caton (2020); Fudge Schormans, Wilton & Marquis (2019); Liddiard et al. (2019); Mellifont (2019) |

| Including lived experience in conducting research about disability | Aboaja et al. (2021); Arblaster (2020); Aubrecht et al. (2021); Boydell et al. (2021); Byrne et al. (2019); Caton (2020); Durose et al. (2011); Fudge Schormans, Wilton & Marquis (2019); Liddiard et al. (2019); Lignou et al. (2019); Mellifont (2019, 2019a); Mellifont et al. (2019); Peer Participation in Mental Health Services (2019); Rhodanthe et al. (2019); Scott et al. (2019) |

| Including lived experience in disseminating and evaluating research about disability | Aboaja et al. (2021); Arblaster (2020); Boydell et al. (2021); Fudge Schormans, Wilton & Marquis (2019); Liddiard et al. (2019); Mellifont (2019, 2019a) |

| Publication type | Reference |

|---|---|

| Journal article | Aboaja et al. (2021); Aubrecht et al. (2021); Byrne et al. (2019); Boydell et al. (2021); Buettgen et al. (2012); Fudge Schormans, Wilton & Marquis (2019); Liddiard et al. (2019); Lignou et al. (2019); Mellifont (2019); Mellifont (2019a); Mellifont et al. (2019) |

| Report | Caton (2020); Durose et al. (2011); Rhodanthe et al. (2019) |

| Thesis | Arblaster (2020); Bynre (2014) |

| Conference paper | Scott et al. (2019) |

| Submission | Peer Participation in Mental Health Services (2019); |

| Book chapter | Burghardt (2023) |

Including lived experience in the design of research about disability

Ten journal articles discussed the relevance of including people with disability in the design of research about disability. Boydell et al. (2021) have recognised that lived experience plays an important role in clearly identifying the research issue that is to be examined. Mellifont (2019) too has reported that by including lived experience early on in the research design process, this inclusion holds potential to reveal research directions that might otherwise remain invisible to non-disabled research teams. Buettgen et al. (2020) discussed the capacity of people with developmental disabilities to shape, guide and clarify the research process. Aubrecht et al. (2021) noted the expertise of co-researchers with lived experience of disability in the advancement of disability research projects. Fudge Schormans, Wilton and Marquis (2019) reported about researchers with disability gaining increased control in the setting research direction. Burghardt et al. (2023) in their book chapter highlighted a need to involve researchers with disability in the setting of research questions. Liddiard et al. (2019) have cautioned in their scholarly article of a need to challenge the norms and ‘rules’ of research so as to enable broader access to and control of the research agenda. Furthermore, lived experience of disability can play a fundamental role in informing about the design of data collection methods, the planning of analysis techniques, as well as how results of the disability research project are to be reviewed and disseminated (Arblaster, 2020). A research report by Caton (2020) has made the following two key points: a) through previous experience in research teams and leadership roles including board membership positions, researchers with disability can confidently voice their opinions and make research decisions; and b) an inclusive and respectful research environment is one where power is shared, people work collaboratively together, and different perspectives are valued. Byrne et al. (2019) have described lived experience led research as supportive of meaningful research design.

Eight publications covered disability research from the perspective of designing of flexible research environments that are accommodating of the needs of people with lived experience of disability. In their journal article, Mellifont et al. (2019) have recognised that universities in Australia need to be more inclusive and accommodating of academics with disability. Supporting these inclusive work settings, a thesis by Arblaster (2020) has argued that researchers with disability should have consistent access to supports wherever required. Aubrecht et al. (2021) have discussed the topic of flexible data collection through which co-researchers with disability utilised Zoom technology in their conducting of interviews. Moreover, a journal article and research report have each respectively highlighted that individual comfort zones need to be established and respected, and choices availed in terms of the intensity of research tasks to be undertaken (Aboaja et al., 2021; Caton, 2020). The design of research team meetings can also support inclusion through a scheduling of times that suit colleagues with disability, allowing breaks in lengthy discussions, and including flexible options to traditional face-to-face meetings by utilising technologies such as Skype (Liddiard et al., 2019). The scholarly literature has cautioned, however, that the design of accommodating research settings for people with lived experience of disability can be constrained by the detrimental impacts of disability stigma and ableism. It is these invisible barriers to inclusion that need to be identified and redressed (Byrne, 2014; Mellifont et al. 2019).

Including lived experience in conducting research about disability

Five journal articles discussed the topic of lived experience-led research. Mellifont (2019a) has purported that there needs to be more persons with lived experience of disability leading research that can generate knowledge about people with disability. These researchers can take a lead in co-creating relevant solutions with and for consumers around issues that are difficult and non-linear (Boydell et al., 2021). Liddiard et al. (2019) has reported that instead of being excluded as leaders, people with disability can be welcomed into meaningful research leadership roles. Byrne et al. (2019) have depicted lived experience led research as an emerging best practice strategy for increasing understanding. While Mellifont et al. (2019) have cautioned about ableism and its destructive role in alienating scholars with disability, the authors have also recognised the power of activism to advance a more inclusive academy that better values lived experience led research.

Eight publications discussed the benefits of research about disability that is co-produced with persons with lived experience. In their journal article, Boydell et al. (2021) have described this research as helping to generate innovative and meaningful interventions. The research report by Caton (2020) has reflected on reciprocity in the sense that researchers with and without lived experience can benefit from working with one another. A research report by Rhodanthe et al. (2019) has also described co-designed research as enabling people with lived experience to undertake research roles where their abilities are best utilised. Mellifont et al. (2019) have called for a greater emphasis in relation to the demand side of disability employment by broadly communicating the benefits of co-produced research. Durose et al. (2011) reported co-production of research in terms of assisting universities to become embedded within their communities. Aubrecht et al. (2021) have described co-researchers with disability enriching the research process through their experiential insight. Fudge Schormans, Wilton and Marquis (2019) reported researchers with lived experience of disability acknowledging the value that they bring to disability research production. Lignou et al. (2019) discussed the potential of co-production to contribute to innovation in the production of knowledge in mental health research.

Five publications discussed the importance of developing the capacity of people with lived experience to do research. In their conference paper, Scott et al. (2019) have advised that training should be provided to meet the needs of some people with disability who might have limited experience in conducting research. Aboaja et al. (2021) in their scholarly article have described a Discovery Group program consisting of eight sessions that were each designed to encourage patient-led research in a mental health facility. Furthermore, Arblaster (2020) has suggested that lived experience research training programs can assist to inform theoretical knowledge about research. The report of Caton (2020) too has underlined the importance of valuing persons with lived experience and taking the necessary measures to unleash their potential. Nonetheless, a submission to the Australian Productivity Commission Inquiry into Mental Health has cautioned that lived experience roles still tend to be misunderstood and poorly supported (Peer Participation in Mental Health Services, 2019).

Two publications have raised the issue of recompensing people with disability for their research work together with their lived experience expertise. In their research article, Aboaja et al. (2021) have asserted a best practice recommendation that people with lived experience who participate in research be commensurately reimbursed for their contributions and time. The thesis by Arblaster (2020) has also recognised that practical experience should be remunerated.

Including lived experience in disseminating and evaluating research about disability

Four scholarly publications discussed the inclusion of lived experience in the context of disseminating and/or evaluating research findings. Aboaja et al. (2021) have noted that lived experience can assist in identifying policy areas for improvement. Mellifont (2019a) having cautioned that disability research conducted by non-disabled researchers do not occur in an ideologically free vacuum, also recommended the participation of researchers with lived experience of disability in the dissemination of validated and culturally relevant information. Fudge Schormans, Wilton and Marquis (2019) described researchers with disability as feeling a sense of empowerment through their involvement in research dissemination activities. Furthermore, the disability inclusion mantra of ‘nothing about use without us’ underlines the need to include lived experience of disability in the dissemination stage of research (Arblaster, 2020).

Three scholarly publications described the role of researchers with lived experience supporting evidence-based policy that can improve the lives of people with disability. Liddiard et al. (2019) recognised that co-researchers with lived experience can hold a desire to support change at a societal level. Arblaster (2020) reported about a policy expectation for the inclusion of lived experience of disability in research about mental health. Service user led research was also said to be powerful in terms of its capacity to broadly impact upon how mental health services are to be delivered by encouraging these services to be respectful of service users (Mellifont, 2019).

Two scholarly publications reported about how researchers with lived experience of disability can help to deliver research findings that are accessible and understandable. Arblaster (2020) noted that participatory research approaches help to ensure that research is accessible and acceptable to the target audience. Lived experience was also said to inform information translation strategies (i.e., Plain English summaries) to assist understanding among a diverse population of individuals who experience mental ill health (Boydell et al., 2021).

Inclusion of lived experience in disability research assessment tool

Addressing the second of the research aims, Table 3 provides a practical, fourteen-question assessment tool. Being informed by this rapid review, this evidence-based tool is designed to be applied prior to the commencement of disability research. Mapping against Arnstein’s model of citizen participation, the tool supports an inclusion of researchers with disability at levels matching with their fullest abilities in disability research. For some, this will be on the highest level (i.e., rung) of participation as lead researchers, while others can actively participate and be valued as co-researchers. On occasions where answers to assessment questions are recorded as ‘yes’, the research team is said to be taking pragmatic steps to being inclusive of researchers with lived experience of disability. Conversely, where responses are in the negative or are uncertain (i.e., ‘not sure’), an additional question is warranted. This question is, to what possible extent has ableism influenced these decisions? Through a consistent answering of questions in the affirmative, this pragmatic tool endeavours to encourage disability research teams to be more inclusive of researchers with disability.

| Theme (Topic) | Yes | No | Not sure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Including researchers with disability in the design of disability research: | |||

| 1) is the research direction/ aim(s)/ question(s) to be informed by researchers with disability? | □ | □ | □ |

| 2) is the design of methods to be informed by researchers with disability? | □ | □ | □ |

| 3) will researchers with disability be reasonably accommodated throughout the research project? | □ | □ | □ |

| 4) are funding sources targeted that require the inclusion of researchers with disability in disability research teams? | □ | □ | □ |

| 5) is the work environment designed to be inclusive of researchers with disability by redressing potential for stigma or discrimination? | □ | □ | □ |

| 6) is the work environment accessible for researchers with disability? | □ | □ | □ |

| Including people with disability in conducting disability research: | |||

| 7) is the disability research to be led by researcher(s) with disability? | □ | □ | □ |

| 8) are researchers with disability to be included as co-researchers? | □ | □ | □ |

| 9) are researchers with disability to be fairly recompensed for their abilities and research contributions through financial payments? | □ | □ | □ |

| 10) are researchers with disability to be given opportunities to develop their research skills and capacity? | □ | □ | □ |

| Including people with disability in disseminating and evaluating disability research findings: | |||

| 11) are researchers with disability to be involved in disseminating research findings? | □ | □ | □ |

| 12) are research findings to be disseminated in accessible and understandable ways that are informed by researchers with disability? | □ | □ | □ |

| 13) are researchers with disability to be included in evaluating research outcomes? | □ | □ | □ |

| 14) will lived experience-led or co-produced research findings inform disability policy at international, national and/or state levels? | □ | □ | □ |

Discussion

Addressing the first of the study aims, the results of this rapid review are to be critically discussed across five topic areas. These topics include a review of disability research funding criteria within an inclusive assessment framework, the sharing of power between researchers with and without disability, addressing a lack of career pathways in the academy for researchers with lived experience of disability, and the skills development of researchers with disability where needed and desired.

A greater inclusion of people with lived experience in research about disability commences with a recognition of this experience in disability research funding criteria. Researchers with disability, however, continue to be undervalued in the formulation of this criteria (Mellifont, 2019). Consequently, Banas et al. (2019) have warned of inflexible assessment frameworks that potentially exclude people with lived experience from participating in disability research teams as researchers. An inclusive alternative involves disability research applications having to explain how researchers with lived experience of disability have been included to their fullest abilities. Under this inclusive assessment framework, research funding submissions that fail to include lived experience among research teams who intend to conduct research about disability would be rejected. A consistent application of these inclusive and ethical research funding assessment requirements would assist to redress the current scarcity of people with disability who are employed as researchers in a timely manner.

A focus on creating and maintaining relationships among researchers with and without lived experience is fundamental to the successful sharing of power (Caton, 2020). This sharing of power is reflected in the Australian Government’s 12.5 million dollar National Disability Research Partnership (NDRP). While the NDRP is a good practice example of lived experience led and co-produced research requirements being successfully built into disability research funding criteria (National Disability Research Partnership, 2023), such inclusion is far from commonplace. Future research is therefore needed to examine the possible extent to which non-disabled researchers might be unwilling to share the power and prestige that they currently hold in conducting disability research via their rejection of inclusive research assessment processes. Importantly, while the research work of genuine disability allies needs to be recognised and valued, such research about disability should not occur in isolation (i.e., isolated from the benefits that researchers with disability can bring to the research team, research direction and research outcomes).

Research that is conducted about communities often fail to include the people from these communities (Caton, 2020; Durose et al., 2012). As applied to disability communities in Canada and abroad, this rapid review has revealed that the research careers of people with disability can be given modest attention or ignored entirely. This is not to suggest that all researchers with lived experience of disability will necessarily want to be involved in conducting disability research. But for those who do desire to follow this career path and who currently find themselves on the outside of an academy where ableism continues to survive or in some cases, even thrive (Mellifont et al. 2019), more opportunities for inclusion are clearly needed.

People with disability can benefit from opportunities to develop their research skills wherever such development is needed and desired. This qualification of ‘where needed and desired’ is important as it is ableist to assume that researchers with and without disability are mutually exclusive groups or that researchers with disability will necessarily require skills development. Strnadová et al. (2014), however, have warned that skills training is still largely overlooked among the literature about advancing inclusive disability research. Crucially, this rapid review has revealed a paucity of scholarly literature not only on this particular topic, but more broadly throughout publications specifically referring to lived experience led or co-produced disability research.

Limitations

Being exploratory in nature, this rapid review was purposefully confined to the search terms applied and the databases selected. In addition to a small sample of publications informing this review, examples of limitations as reported among the scholarly texts include: a small volume of articles informing analysis, diversity gaps in the study samples, and a generally small sample size applied (Aboaja et al., 2021; Arblaster, 2020; Mellifont et al., 2019). Hence, the assessment tool as informed by this rapid review, while evidence-based, should nonetheless be considered preliminary in nature. The author thus openly acknowledges the need for testing and evaluation of this tool.

Conclusion

This exploratory review offers a practical tool for researchers (including researchers with disability) who are conducting research about disability and who want to be more inclusive of people with lived experience in their research teams. Crucially, questions need to be asked of researchers who elect to answer in the negative to the prompts that are raised in this paper. If ableism is found to be driving any of these responses, and should there be no desire on behalf of the decision-makers to become educated about the benefits of lived experience led and co-produced research, perhaps it is their research careers that need to be brought into question. Such questioning holds compatibility with an enlightened academy as an inclusive, progressive, and open-minded place. A place that proudly shines as a beacon of diversity and inclusion for others to follow.

References

- Aboaja, A., Atewogboye, O., Arslan, M., Parry-Newton, L., & Wilson, L. (2021). A feasibility evaluation of Discovery Group: determining the acceptability and potential outcomes of a patient-led research group in a secure mental health inpatient setting. Research Involvement Engagement, 7.

- Arblaster, K. (2020). Investing in the Future: Integrating Lived Experience Perspectives in Mental Health Curriculum Design and Evaluation in Entry-Level Occupational Therapy Education. Sydney: University of Sydney.

- Arnstein, S.R. (1969) A ladder of citizen participation, Journal of the American

- Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216-224.

- Arnstein, S. R. J. C. p. E. c. c. (1971). Eight rungs on the ladder of citizen participation. Citizen participation: Effecting community change, 66-91.

- Aubrecht, K., Barber, B., Gaunt, M., Larade, J., Levack, V., Earl, M., & Weeks, L. E. (2021). Empowering younger residents living in long-term care homes as co-researchers. Disability & Society, 36(10), 1712-1718.

- Banas, J. R., Magasi, S., The, K., & Victorson, D. E. J. Q. H. R. (2019). Recruiting and retaining people with disabilities for qualitative health research: Challenges and solutions. Qualitative Health Research, 29(7), 1056-1064.

- Barnes, C., & Mercer, G. (1997). Breaking the mould? An introduction to doing disability research. Doing disability research, 1, 1-4.

- Barnes, C., & Sheldon, A. (2007). Emancipatory disability research and special educational needs. The Sage handbook of special education, 233-246.

- Beckett, K., Farr, M., Kothari, A., Wye, L., & Le May, A. (2018). Embracing complexity and uncertainty to create impact: exploring the processes and transformative potential of co-produced research through development of a social impact model. Health research policy and systems, 16(1), 1-18.

- Beresford, P. (2000). What have madness and psychiatric system survivors got to do with disability and disability studies? Disability & Society, 15(1), 167-172.

- Bowers, L., Whittington, R., Nolan, P., Parkin, D., Curtis, S., Bhui, K., . . . Simpson, A. J. T. B. J. o. P. (2008). Relationship between service ecology, special observation and self-harm during acute in-patient care: City-128 study.The British Journal of Psychiatry193(5), 395-401.

- Bovill, C., & Bulley, C. J. (2011). A model of active student participation in curriculum design: exploring desirability and possibility. In Rust, C. Improving Student Learning Global theories and local practices: institutional, disciplinary and culturalvariations. Oxford: The Oxford Centre for Staff and Educational Development.

- Boydell, K. M., Honey, A., Glover, H., Gill, K., Tooth, B., Coniglio, F., . . . Health, P. (2021). Making Lived-Experience Research Accessible: A Design Thinking Approach to Co-Creating Knowledge Translation Resources Based on Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9250.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. J. Q. r. i. p. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology.Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Buettgen, A., Richardson, J., Beckham, K., Richardson, K., Ward, M., & Riemer, M. (2012). We did it together: A participatory action research study on poverty and disability. Disability & Society, 27(5), 603-616.

- Burghardt, M., Breton, N., Findlay, M., Pollock, I., Rawlins, M., Woo, K., & Zinyk, C. (2023). Sol Express in the Time of COVID-19: Reflections from a Creative Arts Participatory Research Project. In Disability in the Time of Pandemic(Vol. 13, pp. 175-192). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Byrne, L. (2014). A grounded theory study of lived experience mental health practitioners within the wider workforce. Central Queensland University. PhD thesis 2013. Retrieved from http://www. cqu. edu. au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/100052 …,

- Byrne, L., Wang, Y., Roennfeldt, H., Chapman, M., & Darwin, L. (2019). Queensland framework for the development of the mental health lived experience workforce. Retrieved from https://www.qmhc.qld.gov.au/engage-enable/lived-experience-led-reform/peer-workforce

- Campbell, F. (2009). Contours of ableism: The production of disability and abledness. UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Caton, S. (2020). Evaluation of the Experiences of the Greater Manchester Growing Older with Learning Disabilities (GM GOLD) Co-Researchers. In: Manchester, UK: Manchester Metropolitan University.

- Centre for Disability Research and Policy, (2023). A better life for people with disability around the world. Retrieved from https://www.sydney.edu.au/medicine-health/our-research/research-centres/centre-for-disability-research-and-policy.html

- Darby, S. (2017). Making space for co‐produced research ‘impact’: learning from a participatory action research case study. Area, 49(2), 230-237.

- Deakin University. (2021). HDR Literature Review Plan. Retrieved from https://deakin.libguides.com/c.php?g=929473&p=6716905

- Durose, C., Beebeejaun, Y., Rees, J., Richardson, J., & Richardson, L. (2011). Towards co-production in research with communities. Swindon: AHRC.

- Entwistle, V. A., Renfrew, M. J., Yearley, S., Forrester, J., & Lamont, T. (1998). Lay perspectives: Advantages for health research. British Medical Journal, 316(7129), 463.

- Faulkner, A. (2017). Survivor research and Mad Studies: the role and value of experiential knowledge in mental health research. Disability & Society, 32(4), 500-520.

- Fothergill, A., Mitchell, B., Lipp, A., & Northway, R. J. J. o. R. i. N. (2013). Setting up a mental health service user research group: a process paper. Journal of Research in Nursing, 18(8), 746-759.

- Fudge Schormans, A., Wilton, R., & Marquis, N. (2019). Building collaboration in the co‐production of knowledge with people with intellectual disabilities about their everyday use of city space. Area, 51(3), 415-422.

- Harker, J., & Kleijnen, J. (2012). What is a rapid review? A methodological exploration of rapid reviews in Health Technology Assessments. International Journal of Evidence‐Based Healthcare, 10(4), 397-410.

- Jennings, H., Slade, M., Bates, P., Munday, E., & Toney, R. J. B. p. (2018). Best practice framework for Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) in collaborative data analysis of qualitative mental health research: methodology development and refinement. BMC psychiatry, 18(1), 1-11.

- Khangura, S., Konnyu, K., Cushman, R., Grimshaw, J., & Moher, D. (2012). Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic reviews, 1(1), 1-9.

- Landry, D. (2017). Survivor research in Canada:‘Talking’recovery, resisting psychiatry, and reclaiming madness. Disability & Society, 32(9),1–21.

- LeFrançois, B. A., Menzies, R., & Reaume, G. (Eds.). (2013). Mad matters: A critical reader in Canadian mad studies. Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Liddiard, K., Runswick‐Cole, K., Goodley, D., Whitney, S., Vogelmann, E., Watts MBE, L. J. C., & Society. (2019). “I was Excited by the Idea of a Project that Focuses on those Unasked Questions” Co‐Producing Disability Research with Disabled Young People. Children & Society, 33(2), 154-167.

- Lignou, S., Capitao, L., Hamer-Hunt, J. M., & Singh, I. (2019). Co-production: an ethical model for mental health research?. The American Journal of Bioethics, 19(8), 49-51.

- Milner, P., & Frawley, P. (2019). From ‘on’to ‘with’to ‘by:’People with a learning disability creating a space for the third wave of inclusive research. Qualitative Research, 19(4), 382-398.

- Mellifont, D. (2019). Shifting neurotypical prevalence in knowledge production about the mentally diverse: a qualitative study exploring factors potentially influencing a greater presence of lived experience-led research. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 8(3), 66-94.

- Mellifont, D. (2019a). Non-disabled Space Invaders! A Study Critically Exploring the Scholarly Reporting of Research Attributes for Persons With and Without Disability. Studies in Social Justice, 13(2), 304-321.

- Mellifont, D., Smith-Merry, J., Dickinson, H., Llewellyn, G., Clifton, S., Ragen, J., & Williamson, P. (2019). The ableism elephant in the academy: A study examining academia as informed by Australian scholars with lived experience. Disability & Society, 34(7-8), 1180-1199.

- National Disability Research Partnership (2023). About the NDRP. Retrieved from https://www.ndrp.org.au/about

- Oliver, M. (1992). Changing the social relations of research production?. Disability, handicap & society, 7(2), 101-114.

- Olsen, A., & Carter, C. J. T. L. D. R. (2016). Responding to the needs of people with learning disabilities who have been raped: co-production in action. Tizard Learning Disability Review.

- Peer Participation in Mental Health Services. (2019). Submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry into Mental Health. Retrieved from https://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/240395/sub179-mental-health.pdf

- Rhodanthe, L., Emery, W., & Robyn, M. (2019). All I need is someone to talk to. Perth: Curtin University.

- Rose, D. (2015). The contemporary state of service-user-led research. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(11), 959-960.

- Scott, P., & Koslowski, A. (2019). Negotiating independent ethical review of co-produced disability research: issues and lessons. Retrieved from https://the-sra.org.uk/common/Uploaded%20files/SRA/Presentations/Annual%20Conference%202019/AM/scott%20and%20koslowski.pdf

- Simpson, A. (2013). Setting up a mental health service user research group: A process paper. Journal of Research in Nursing, 18(8), 760-761.

- Sin, C. H., & Fong, J. J. C. s. g. (2010). Commissioning research, promoting equality: reflections on the Disability Rights Commission's experiences of involving disabled children and young people. Children's geographies, 8(1), 9-24.

- Smith, L., & Bailey, D. (2010). What are the barriers and support systems for service user-led research? Implications for practice. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 5(1), 35–44.

- Solis, S. (2006). I'm “coming out” as disabled, but I'm “staying in” to rest: Reflecting on elected and imposed segregation. Equity Excellence in Education, 39(2), 146-153.

- Strnadová, I., Cumming, T. M., Knox, M., Parmenter, T., & Disabilities, W. t. O. C. R. G. J. J. o. A. R. i. I. (2014). Building an inclusive research team: The importance of team building and skills training. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(1), 13-22.

- Sweeney, A. (2016). Why mad studies needs survivor research and survivor research needs mad studies. Intersectionalities: A Global Journal of Social Work Analysis, Research, Polity, and Practice, 5(3), 36-61.

- Tricco, A. C., Langlois, E., Straus, S. E., & World Health Organization. (2017). Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. World Health Organization.

- Voronka, J. (2016). The politics of 'people with lived experience' Experiential authority and the risks of strategic essentialism. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 23(3), 189-201.

- Walmsley J and Johnson K (2003) Inclusive Research with People with Learning Disabilities Past, Present and Futures. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Wykes, T. (2003). Blue skies in the Journal of Mental Health? Consumers in research. Journal of Mental Health, 12(1), 1-6.