Natural Support for Canadians with Disabilities: A Scoping Review

Soutien naturel pour les Canadiennes et Canadiens handicapés : une étude de la portée

Julia Jansen-van Vuuren

Post-Doctoral Fellow, Rehabilitation Therapy

Queen's University

17jmjv [at] queensu [dot] ca

Monique Nelson

Director of Community Engagement

posAbilities

Queen's University

1MNelson [at] posabilities [dot] ca

Heather Plyley

PhD Candidate, Sociology

Queen's University

heather [dot] plyley [at] queensu [dot] ca

Donna Thomson

Family Advisor

McMaster University

donna4walls [at] gmail [dot] com

Caitlin Piccone

PhD Candidate, Rehabilitation Therapy

Queen's University

0cm54 [at] queensu [dot] ca

Linda Perry

Special Projects Coordinator

Vela Canada

lindaperry [at] velacanada [dot] org

Navjit Gaurav

PhD Candidate, Rehabilitation Therapy

Queen's University

19ng7 [at] queensu [dot] ca

Xiaolin Xu

Research Coordinator, Rehabilitation Therapy

Queen's University

xx4 [at] queensu [dot] ca

Rebecca Pauls

Executive Director

Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network

rpauls [at] plan [dot] ca

Heather M. Aldersey

Associate Professor, Rehabilitation Therapy

Queen's University

hma [at] queensu [dot] ca

Abstract

Background: Natural supports provide crucial emotional, informational, and instrumental support for people with disabilities and can facilitate social inclusion and belonging. Minimal research explores natural support in Canadian contexts for people with disabilities. Purpose: This scoping review identifies how natural supports for adults with disabilities in Canada are described in published research literature. Method: Using Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework, coupled with recommendations from Levac et al., and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for scoping reviews, we searched a range of academic databases for relevant empirical studies related to the following research question: How are natural supports for adults with disabilities in Canada described in published research literature? Results: Fifteen articles met the inclusion criteria. Family and non-family support systems and other social networks provided crucial natural support to Canadians with disabilities. We organized content related to the role of natural supports into the categories of: (a) being financially secure; (b) contributing to and participating in caring and inclusive communities; (c) being respected and empowered to make decisions; (d) knowing the loving support of friends and family; and (e) choosing a place to live and call home. Caregiver burnout and stigmatization of disability were reported as barriers to natural support, and formal and natural support provision at times, overlapped. There was a notable absence of information related to having a well-planned future, and limited diverse representation in the studies. Conclusion: Support is vital to the wellbeing of individuals with disabilities in many different life domains. This scoping review reveals a dearth of research on natural supports in Canada, and calls for increased engagement with and recognition of natural supports from a diversity of perspectives.

Résumé

Contexte : Les proches aidant·es sont une source de soutien émotionnel, informationnel et instrumental crucial pour les personnes handicapées. Ces personnes peuvent faciliter leur inclusion et leur sentiment d’appartenance au sein de la société. Peu d’études explorent le rôle de ce soutien naturel pour les personnes handicapées en contexte canadien. Objectif : Notre étude de la portée caractérise la manière dont le soutien naturel pour les adultes handicapés au Canada est décrit dans la littérature scientifique publiée. Méthodologie : À partir du cadre d’étude de la portée développé par Arksey et O’Malley, en association avec les recommandations de Levac et coll. et les lignes directrices PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) spécifiques aux études de la portée, nous avons fouillé une gamme de bases de données universitaires à la recherche d’études empiriques pertinentes en lien avec la question de recherche suivante : Comment décrit-on le soutien naturel pour les adultes handicapés au Canada dans la littérature scientifique publiée? Résultats : Quinze articles répondaient aux critères d’inclusion. Les systèmes de soutien familial et non familial ainsi que d’autres réseaux sociaux ont fourni un soutien naturel crucial aux Canadiennes et Canadiens handicapés. Nous avons divisé le contenu en lien avec le rôle des proches aidant·es dans les catégories suivantes : (a) se dote d’une sécurité financière; (b) contribuer et participer à des communautés bienveillantes et inclusives; (c) être respecté et habilité à prendre des décisions; (d) connaitre le soutien affectueux de ses ami·es et de sa famille; et (e) choisir un endroit où vivre et appeler chez soi. L’épuisement professionnel des proches aidant·es et la stigmatisation du handicap ont été signalés comme des obstacles au soutien naturel, et les prestations de soutien formel et naturel se chevauchaient parfois. Les études démontraient une absence notable d’informations relatives à la bonne planification du futur ainsi qu’une représentation diversifiée limitée. Conclusion : Le soutien est essentiel au bienêtre des personnes handicapées dans de nombreux domaines de la vie. Cette étude de la portée révèle un manque de recherche sur les proches aidant·es au Canada et appelle à une meilleure mobilisation et reconnaissance des sources de soutien naturel, et ce, sous divers angles.

Keywords: Natural support, Canadians with disabilities, access to support, family support network, non-family support, social support, social networks, social inclusion, scoping review.

Mots clés : Soutien naturel, Canadien·nes handicapé·es, accès au soutien, réseau de soutien familial, soutien non familial, soutien social, réseaux sociaux, inclusion sociale, étude de la portée.

Introduction

Relationships are foundational for human flourishing and wellbeing and provide an important source of emotional and practical support to enhance function. In the realm of disability studies, support is a multifaceted concept characterized by the types of networks and the nature of assistance provided to individuals with disabilities. Research often distinguishes between formal and natural or informal support (hereafter we will exclusively use the term ‘natural support’). Formal support is typically defined as paid private or government-funded, professional services; and natural support is defined as incorporating a broad range of unpaid or voluntary support, often from family or friends (Duggan & Linehan, 2013; Reynolds et al., 2018). Bigby (2008) described natural support as “derived from relationships with family, friends, neighbours and acquaintances, and is based on personal ties rather than payment” (p.148). Similarly, Swedish families of children with disabilities described natural support in terms of relationships with others and “as an expression for a life-enriching togetherness” (Lindblad et al., 2007, p. 244). Another study categorized natural support into care network types – lone spouse, children at home, spouse and children, close kin and friends, older diverse, younger diverse (Keating & Dosman, 2009). Based on previous literature, we defined natural support broadly as unpaid support provided in a relational capacity to persons with disabilities.

Despite the distinctions made between natural and formal support, the terms used to describe these supports are varied. While some studies explicitly categorized supports as formal, informal, or natural (Keating & Dosman, 2009; Friesen et al., 2010; Lapierre & Keating, 2013; Rudman et al., 2016; Naganathan et al., 2016; Potvin et al., 2016; Petner-Arrey et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2019; Heifetz et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021), others discussed them in terms of social support, supportive social relationships, social circles, or social networks (King et al., 2006; Casey & Stone, 2010; Berry & Domene, 2015; Sallafranque-St-Louis & Normand, 2017; McConnell et al., 2022). Groups of people who voluntarily but intentionally provide natural support to people with disabilities have also been referred to as ‘personal support networks’ (Hillman et al., 2013; Shelley et al., 2018) or ‘circles of support’ (Araten-Bergman & Bigby, 2022). Regardless of terminology, the literature highlights the significance of interpersonal and community connections in supporting individuals with disabilities.

Building personal support networks of diverse but committed people around individuals with disabilities can help them to achieve a ‘good life’, including happiness, safety, being listened to and respected, contributing to society, having meaningful relationships, autonomy, life-long development, and a balanced life (Hillman et al., 2012). Various disability support and advocacy organizations promote a ‘good life’ in their vision and mission. For example in Canada, Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network (PLAN) and Vela Canada seek to support individuals with disabilities and their families to think about and define what a good life looks like and support them in their goals and priorities (PLAN, 2023; Vela Canada, 2022). Similarly, posAbilities has a vision for “Good and full lives. For everyone”, including “physical and mental health, relationships, financial security, and living a virtuous life… having a breadth and depth of life experience, overcoming fears, introspection, gratitude, positivity and self-realization” (posAbilities, 2018, p. 1). According to PLAN (2023), a ‘good life’ consists of (a) being financially secure; (b) contributing to and participating in caring and inclusive communities; (c) being respected and empowered to make decisions; (d) knowing the loving support of friends and family; (e) choosing a place to live and call home; and (f) having a well-planned future. We drew on PLAN’s concept of a ‘good life’ specifically, to organize the reporting of our results as we believe this approach creates a clearer link to the reality of people and communities engaged in natural support on the ground – ideally enabling results from this study to be relevant and actionable for natural support advocates.

Historically, the bulk of research about support in disability centres on understanding and improving formal support (e.g., psychosocial interventions, occupational therapy, social work, government benefits). We argue that similar explorations of natural supports – both what is working and what could be improved or expanded – is equally, if not more, important for the lives of persons with disabilities and their families. To inform this exploration, we conducted a scoping review which aimed to understand how natural supports for people with disabilities in Canada are described in published literature. Our goal to understand the state of existing research on natural supports in the Canadian context was twofold: (a) to inform future research directions related to natural supports in Canada; and (b) to inform policy and practice by equipping natural support advocates with information they can use to drive future conversations.

Methods

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) seminal guidelines for scoping reviews, coupled with recommendations from Levac et al. (2010), and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018). In particular, we sought engagement from important stakeholders in the Canadian disability context, including persons with disabilities, family advocates, and leaders of disability support organizations (Levac et al., 2010). We initially identified the research question – How are natural supports for adults with disabilities in Canada described in published research literature? However, we recognized the ambiguity of current definitions and anticipated that our search would help to refine our understanding of natural support. Hence, we included terms such as natural support, informal support, personal support network, community network, and circle of support, to capture different terminologies that describe similar types of support.

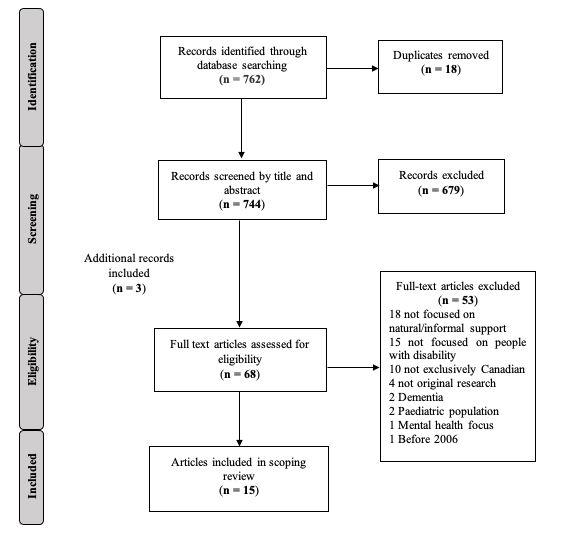

For the second and third steps, identifying relevant studies and study selection, we consulted Health Sciences and Sociology librarians to search databases and identify appropriate keywords. We developed inclusion and exclusion criteria iteratively through discussion amongst the authors and the larger research team (Table 1). Once keywords were confirmed, we searched the following databases: CINAHL, Medline, PsycInfo, Web of Science, and Sociological Abstracts. Using Covidence software, two authors independently screened articles by title and abstract, and a third author screened and decided on articles where there was a conflict. Again, two authors independently screened full-text articles according to our inclusion criteria, and a third author resolved any conflicts. The authors also screened the reference lists of included articles and used Google Scholar and conversations with natural support advocates to identify other potential sources. Figure 1 (PRISMA diagram) depicts the article selection process.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| • Focus of support is on adults with disabilities (ages 18+) | •Support primarily for family/caregivers or for children with disabilities (under age 18) |

| •Describes provision of natural support | •Individuals with HIV/AIDS, Dementia, acute illness, chronic disease, or cancer without a focus on disability |

| •Published after 2006 | •Published before 2006 |

| •Peer-reviewed original research (i.e., empirical studies reporting original findings/results, regardless of the study design: qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods) | •Theoretical paper/editorial/reviews/short report/author recommendations/grey literature |

We included 15 full-text, peer-reviewed, original articles from 2006 onwards, as this aligned with the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN, 2007), which explicitly affirmed the human rights of people with disabilities to receive both formal and natural support. In the next stage of charting the data, the authors systematically analyzed the included articles to extract relevant information related to the definition or description of natural supports. We used a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet with pre-determined headings to extract data. Authors independently extracted data from the included articles before meeting regularly to discuss the extraction process and theme development.

Results

General Description of Studies

Within the 15 included studies the ages of participants ranged from 19 years to 65+. Most research was conducted in Ontario (n=8), with other studies conducted in Alberta (n=1), Manitoba (n=1), and in areas across Canada excluding Yukon and Northwest Territories (n=2). Several studies did not state the specific provinces/territories (n=3). No studies explicitly included perspectives from Indigenous Peoples or immigrants to Canada. Eleven of the included studies used qualitative design, two studies used a quantitative design, and two studies employed a mixed-methods research design. See Appendix Table 3 for further details about the included studies’ populations, types of disabilities, sample size, research design and study aims. Table 2 highlights some of the characteristics of natural support networks described in the included studies.

| Family support systems | Parents | King et al., 2006; Potvin et al., 2016; Petner-Arrey et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2019; Heifetz et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021 |

| Partners/spouses | Keating & Dosman, 2009; Friesen et al., 2010; Naganathan et al., 2016; Heifetz et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021 | |

| Children | Keating & Dosman, 2009; Rudman et al., 2016; Naganathan et al., 2016; Potvin et al., 2016 | |

| Siblings | King et al., 2006; Potvin et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2019; Heifetz et al., 2019 | |

| Extended Family | Keating & Dosman, 2009; Potvin et al., 2016; Heifetz et al., 2019 | |

| Non-family support systems | Neighbours | Friesen et al., 2010; Lapierre & Keating, 2013; Rudman et al., 2016; Naganathan et al., 2016; McConnell et al., 2022 |

| Church communities | Casey & Stone, 2010; Friesen et al., 2010; Berry & Domene, 2015; Rudman et al., 2016; Petner-Arrey et al., 2016 | |

| Cultural communities | Rudman et al., 2016 | |

| Educational institution staff | King et al., 2006; Berry & Domene, 2015 | |

| Employers/coworkers/employees | Friesen et al., 2010; Berry & Domene, 2015; Petner-Arrey et al., 2016 | |

| Other social network supports | Volunteer opportunities | Petner-Arrey et al., 2016 |

| Disability-specific support groups | Casey & Stone, 2010 | |

| Online platforms | Sallafranque-St-Louis & Normand, 2017; Heifetz et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021 |

Supporting a ‘Good Life’

We categorized findings from the included articles related to the role of natural supports using the elements of a ‘good life’ as described by PLAN (2023); however, we were unable to find data that aligned with PLAN’s concept of “having a well-planned future”. We further classified the findings within the ‘good life’ elements based on the sources of natural support, distinguishing between family support systems and non-family support systems. Outside of the ‘good life’ framework we added several inductively derived themes, including barriers to natural support, and balancing and overlapping natural and formal supports.

Being Financially Secure

Most of the findings under this heading related to natural supports for employment. Studies showed that family support, especially parental support, played a significant role in contributing to the career development and workplace success of individuals with disabilities (Berry & Domene, 2015; Petner-Arrey et al., 2016). Berry and Domene (2015) highlighted the importance of parental support for youth pursuing career-related goals, including holding high expectations, providing emotional and psychological support, and offering encouragement. This, in conjunction with tangible career-related support throughout their education and transition into the workplace, increased individuals’ self-esteem and belief in their ability to succeed (Berry & Domene, 2015). Another study found that parental support was an important factor in securing employment or volunteer opportunities, as parents were instrumental in creating networks for their children to connect them to potential employers/volunteer supervisors (Petner-Arrey et al., 2016). Parental support was also provided throughout employment to help sustain employment opportunities long-term e.g., helping carrying newspapers on a paper route, teaching their child how to use a GPS and accompanying them on early pizza deliveries, modelling expectations for interactions with patrons, as well as explaining job expectations (Petner-Arrey et al., 2016). In some cases, parents would communicate with employers about their child’s strengths and advocate for accommodations or alternative role expectations (Petner-Arrey et al., 2016).

In terms of non-family support systems, the roles of friends and community members and organizations were highlighted as crucial in helping individuals with disabilities succeed in their educational pursuits and career objectives (Berry & Domene, 2015; Petner-Arrey et al., 2016). For instance, peer support assisted students during the transition to higher education and into adulthood and boosted their social interactions (Berry & Domene, 2015). Community members (some natural and some paid) helped students feel connected and supported during their education by increasing their level of community involvement and practical experiences that directly aligned with their vocational aspirations (Berry & Domene, 2015).

Contributing to and Participating in Caring and Inclusive Communities

When looking at the ways that support-receivers understood themselves in relation to those who provided them with support, a common finding was that people wanted to be able to reciprocate and contribute to their communities (Casey & Stone, 2010; Friesen et al., 2010). Regarding the family support that people received, some of them experienced feelings of guilt or unease about over-burdening their spouses, parents, or children and expressed a desire to carry out tasks on their own to the greatest extent achievable (Casey & Stone, 2010; Keating & Dosman, 2009; Naganathan et al., 2016; Rudman et al., 2016).

In terms of the support received from community, individuals with disabilities valued their independence and the ability to give back to their communities. In the study by Casey and Stone (2010), participants “viewed themselves as having something to offer others, and to function as full members of society” and valued the opportunity to be involved in volunteer work (p.357). In a study involving farmers with acquired disability, being able to reciprocate increased feelings of independence and determination, which were seen as positive attributes that aided in adapting to life with a disability (Friesen et al., 2010). Participation in these ways was reported to help with feelings of autonomy (Friesen et al., 2010; Heifetz et al., 2019). In a study with mothers with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), independence was seen as something to be desired, and they valued support from both formal and natural sources that built confidence and enabled independence and autonomy (Heifetz et al., 2019).

Being Respected and Empowered to Make Decisions

Taylor and colleagues (2019) discussed the role of parents in ensuring safe decision-making for individuals with IDD. Parents identified setting limits and scaffolding their level of support based on their family member’s needs so as not to force independence in unmanageable/unsafe ways. This type of collaborative decision making provided encouragement to their family member which increased confidence, but allowed for intervention if needed (e.g., if situations became exploitative/abusive) (Taylor et al., 2019).

While natural support that fostered independence and autonomy was important and appreciated by individuals with disabilities, several studies demonstrated that natural support providers, especially family members, sometimes ignored the support receiver’s wants, needs, and desires (Naganathan et al., 2016; Potvin et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2021). This highlighted how too much involvement may lead to feelings of distrust (Naganathan et al., 2016; Potvin et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2021), as well as the refusal of support or limiting contact with a natural support network to avoid receiving support considered unhelpful (Potvin et al., 2016; McConnell et al., 2022). Despite these insights, the role of non-family support systems in facilitating decision-making and autonomy among individuals with disabilities was not explicitly addressed in included studies.

Knowing the Loving Support of Friends and Family

Multiple studies found that relationships with family and friends were key to social, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing (King et al., 2006; Casey & Stone, 2010; Berry & Domene, 2015; Heifetz et al., 2019). In two studies that looked at the experiences of mothers with IDD, it was found that social relationships with family members provided a combination of emotional support, advice/information sharing, and practical assistance with parental tasks that reduced parenting stress (Heifetz et al., 2019; McConnell et al., 2022). This type of support not only benefitted the individual receiving direct support, but some participants reported that frequent, positive and loving interactions with family members led to similar loving relationships between them and their own children, increasing their parenting satisfaction (McConnell et al., 2022). In addition, family support played a crucial role in improving access to healthcare and other formal support services. Three studies found that family members assisted with transportation and organization of medical appointments, as well as communication with care providers and advocacy (Casey & Stone, 2010; Naganathan et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2021). One of these studies showed that family members travelled long distances to drive the individual with a disability to a different city to give birth (Khan et al., 2021). Other researchers found that mental health support was provided by family members, accompanied by emotional, housing, financial, and childcare support (e.g., respite/childcare, purchasing baby supplies) (Heifetz et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021).

Similar to family support, research showed that friends and online communities were vital in providing social companionship and support (Berry & Domene, 2015; Casey & Stone, 2010; King et al., 2006; Khan et al., 2021). Friendships offered emotional support and fostered feelings of acceptance (King et al., 2006; Berry & Domene, 2015; Casey & Stone, 2010). One study involving postsecondary students with mobility or sensory impairments found that simply having someone to spend time with and talk to was important for an individual’s wellbeing (Berry & Domene, 2015). Other researchers highlighted the value of emotional support from friends who provided active encouragement and belief in individuals with disabilities, as well as the benefit of having a supportive network during challenging times (King et al., 2006; Berry & Domene, 2015).

Additionally, non-kin support providers such as friends and neighbours aided in the safety of the care receiver by ‘keeping an eye out’ for their safety (Naganathan et al., 2016). However, individuals with IDD reported that they had fewer friends and smaller social circles (Khan et al., 2021; Potvin et al., 2016). For them, online socializing was a valuable option, offering a way to overcome the difficulties they faced when trying to connect with others in person (Khan et al., 2021). Three studies found that online platforms aided in a person’s access to connections with friends and family, or making new connections with those in similar situations to themselves (e.g., those with the same type of disability, other mothers with IDD) (Sallafranque-St-Louis & Normand, 2017; Heifetz et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021). With online platforms, there was further access to social companionship, and it was found to be easier for some participants to communicate online rather than face-to-face (Sallafranque-St-Louis & Normand, 2017).

Choosing a Place to Live and Call Home

Three studies reported that natural support systems assisted individuals with disabilities with housing and related needs. Taylor et al. (2019) outlined that adults with IDD were supported by their parents and family in their transition to independent living. The participants noted that support was provided at different stages of independence, with an emphasis on the adult at the centre of the support being able to set the pace of their transition. Support provision included teaching independent living skills such as cooking, cleaning, and general life skills, along with creating an independent living space in their family homes for the family member with a disability to live.

Other findings outlined different types of support that non-kin carers provided with tangible needs, finding that assistance with housekeeping, meals, shopping, and general home maintenance was commonly provided by friends and neighbours (Simplecan et al., 2015). Assistance with personal care and transportation, along with support with bills and banking were found to be beneficial to gaining independence in situations where an individual could potentially feel vulnerable/unsafe (Lapierre & Keating, 2013; Naganathan et al., 2016).

Barriers to Support

Caregiver Burnout

All included studies described barriers to individuals with disabilities receiving or asking for natural support, and burnout of natural supporters was particularly discussed. Studies showed that natural supporter burnout was a result of fatigue, frustration, intensity and involvement of support, and inability to continue balancing/managing many responsibilities (Petner-Arrey et al., 2016; Naganathan et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2019). Support burden was also influenced by the support-receiver over-estimating the capacity of support providers and relying too heavily on their natural support network (Lapierre & Keating, 2013). Increasing age and the emergence of health conditions of the natural support provider were other limiting factors (Naganathan et al., 2016; Keating & Dosman, 2009). Several studies highlighted that families needed to hire external support, but some reported feeling reluctant or guilty to bring in external formal supports, which then added more pressure and expectations on the natural support networks (Keating & Dosman, 2009; Naganathan et al., 2016; Rudman et al., 2016). In some instances, individuals with disabilities limited the amount of natural support they sought because they were aware of the demands this put on family members and did not want to burden them (Rudman et al., 2016; Casey & Stone, 2010).

Stigmatization of Disability

Another barrier to individuals asking for support was stigmatizing attitudes towards disability, both self-stigma and perceived stigma from others. Some individuals resisted asking for assistance with activities they once did on their own, resenting the need to ask others for help (Rudman et al., 2016), or feeling as though asking for help would limit their future independence if they were perceived as incapable (King et al., 2006; Friesen et al., 2010; Petner-Arrey et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2019). Support tended to be avoided by individuals who had previously received unhelpful support, even if well-intentioned (Potvin et al., 2016). Some participants refused support from individuals who expressed negative attitudes about providing support (Potvin et al., 2016), including limiting contact with their families if they were perceived as unhelpful (McConnell et al., 2022). A common theme found in several studies was that some support providers (both formal and natural) disregarded the individual’s wants and needs and ignored/devalued their preferences about how supports should be provided, leading to a lack of trust (Naganathan et al., 2016; Potvin et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2021).

Balancing and Overlapping Natural and Formal Supports

In the majority of studies, natural support was not discussed in isolation. While the focus of this review is on natural support, the included articles made it apparent that it is necessary to balance both formal and natural supports in the lives of most adults with disabilities. For example, older adults with physical disabilities benefited from paid housekeeping support and some felt more comfortable talking about their challenges with a medical professional rather than family (Casey & Stone, 2010). Additionally, pregnant women with IDD described the invaluable support of paid doctors, nurses and case workers for informational, emotional, and instrumental support (Potvin et al., 2016). Several studies discussed emotional support and community connection from paid people within formal institutions and organizations such as educational institution staff (King et al., 2006; Berry & Domene, 2015), employers/coworkers/employees (Friesen et al., 2010; Berry & Domene, 2015; Petner-Arrey et al., 2016), and in some cases, medical and support staff (Berry & Domene, 2015; Potvin et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2021). Some also discussed how formal supports can morph into natural supports. For example, one study found that paid university staff members (e.g., residence assistants, note-takers, instructors) provided support to graduate students with disability and helped foster an inclusive community within the educational setting. This created a network where people would help each other when facing barriers, resulting in social connections/friendships and tangible natural support (Berry & Domene, 2015).

Discussion

This review included 15 empirical studies with adults with disabilities, family members, friends, other non-kin care providers, and formal healthcare providers. Natural support providers were predominantly family members (parents, siblings, partners/spouses, children, and extended family members), but also included friends/peers, and members of the community (church communities, staff at educational institutions, employees/coworkers/employers, volunteer communities, and support groups). These findings reflect general categories of natural support providers in other high-income international contexts, including the USA, Europe, and Australia (Bailey et al., 2020; Kaley et al., 2022; White & Mackenzie, 2015). Our findings emphasize the importance of natural support and offer examples of how natural supports fill a place in a person’s life that in many cases cannot be filled by a formal, paid provider. Along with providing insight into the types of natural supports that people with various disabilities rely on in their daily lives, these findings demonstrate how current research on natural supports in Canada align with the organization PLAN’s articulation of a ‘good life’. These results also highlight barriers to individuals asking for and receiving natural support, including natural support provider burnout and stigma towards disability. Finally, our findings revealed that in most cases, natural support did not exist in isolation from formal supports, and that typically a person must engage with both kinds of supports across their lifespan to meet their disability-related support needs. We identified four main themes from the findings, including the critical role of natural support, the importance of autonomy, reciprocity, and future planning, lack of diverse perspectives, and tensions between formal and natural supports.

The Critical Role of Families and Natural Support Networks

The findings from our review align with global literature demonstrating that, although natural support networks of people with disabilities can be small, they play a crucial role in enhancing quality of life (QOL) and participation, particularly family members (Duggan & Linehan, 2013; Friedman, 2021; Pallisera et al., 2022; Roll & Bowers, 2019; Sanderson et al., 2017; Shelley et al., 2018). Though natural support is important universally, the specific needs and challenges associated with disabilities shape natural support systems differently, setting them apart from those typically seen in the general population. For example, individuals with disabilities can experience more difficulty forming friendships and participating in community activities and often face challenges with social isolation and exclusion (Friedman, 2021). Hence, natural supports provide crucial emotional, informational, and instrumental support for people with disabilities and can facilitate social inclusion and belonging (Simplican et al., 2015). They can support people with disabilities to engage in recreational activities, find and maintain employment, be included in education, or find and maintain suitable housing, amongst other things (Donelly et al., 2010; Kelley & Westling, 2013; Petner-Arrey et al., 2016; Sanderson et al., 2017). Additionally, natural supports, such as friendships, are important for companionship and empathy, mitigating loneliness and improving QOL (Duggan & Linehan, 2013; Tobin et al., 2014). Many individuals with various disabilities rely on families, friends, and non-kin carers primarily for emotional and instrumental support, and these are often intertwined. For example Casey and Stone (2010) described how some older adults with physical impairments had peace of mind knowing they had friends and family available for instrumental support, thus “the provision of instrumental support was simultaneously experienced … as emotional support” (p.353). Our review affirmed that emotional support is essential at every life stage and regardless of disability type, hence trusting, caring relationships need to be nurtured, including with people with profound disability (Hillman et al., 2013; Hughes et al., 2011).

Our review also identified that there can be barriers to natural support such as mismatched expectations, or support provider burnout. It will be important to explore ways to best promote and enable natural support moving forward. For example, formal support providers can facilitate and promote the development of relationships and natural support networks for individuals with disabilities (Araten-Bergman & Bigby, 2022; Duggan & Linehan, 2013). In Canada specifically, there are a number of formal organizations such as PLAN, Vela Canada, and posAbilities, which focus on developing and maintaining ‘personal support networks’ around an individual with disability. These networks are made up of diverse people who genuinely care for the individual and can provide emotional and instrumental support through their various skills and connections (Casey & Stone, 2010). Within these organizations, it is crucial for paid workers to develop meaningful relationships with individuals, becoming part of the natural support networks themselves. Supporting natural supporters is particularly important as well, since caring for others (emotionally and practically) can add responsibilities and burdens that may be difficult to sustain long term, particularly when caregivers’ own health or independence is declining (Bigby et al., 2019; Friedman, 2021). Government policies should also allocate more funding, respite and support for natural supporters, recognising their crucial role in the lives of individuals with disability (Friedman 2021).

Autonomy, Reciprocity, and Support Navigation

Studies in this review highlighted the importance of choice, autonomy, contribution and reciprocity related to the provision of natural support for individuals with disabilities. Like most people, persons with varying disabilities and across the life-span wanted a say in what and how support was given. For example, our findings showed that younger people often valued support with education, independent housing, and parenting, whereas, older adults prioritized support to remain safely at home. Some people with disabilities also resisted always being a ‘care recipient’ and valued the ability to contribute and reciprocate support. Other Australian researchers affirm the need for natural support networks to be ‘person-centred’, respecting the individual’s goals, values, needs, autonomy and contribution, to promote a ‘good life’ (Bigby et al., 2019; Hillman et al., 2013; Hillman et al., 2012; Knox et al., 2016; Shelley et al., 2018). This requires people who know and respect the individual deeply, and who genuinely care about empowering and supporting their participation and wellbeing and offering individuals encouragement and ongoing opportunities to self-actualize..

Genuine relationships and supportive, person-centred networks are especially crucial as some of our findings indicated that natural support can be unhelpful, controlling or limiting, and can negatively affect QOL or further isolate individuals with disabilities. For example, some Canadian mothers with intellectual disabilities found family members’ support, while perhaps well-intentioned, was imposed upon them and in fact restricted their independence and autonomy (Heifetz et al., 2019; Potvin et al., 2016). Risk aversion can be more pronounced in natural support provision for persons with disabilities compared to others in the broader population. Regarding individuals with intellectual disabilities in Australia, Hillman et al. (2012) demonstrated how individual rights and autonomy were sometimes violated due to organizational safety regulations, rigidity, and liability concerns, but also by family members’ safety concerns. Safety is a necessary and important consideration; however, natural support networks must carefully balance autonomy and risk to empower rather than hinder people with disabilities (Araten-Bergman & Bigby, 2022; Hillman et al., 2012; Shelley et al., 2018).

Future planning is another important consideration in supporting autonomy and ensuring a ‘good life’ both in the present and for the future of an individual with a disability. This can involve discussing future options with the individual and other family members/friends, establishing guardianship or power of attorney, arranging housing and finances, and ensuring adequate emotional and instrumental support (Burke et al., 2018; Tomasa & Williamson, 2021). In British Columbia, Representation Agreements (RA) are similar to power of attorney, however they do not have a capacity requirement. An RA is preferred to guardianship as the latter is an instrument that assumes full control over the person with disabilities’ decision making. However, natural support in ‘future planning’ was largely missing from the studies in our review, highlighting a need for greater recognition and development in the Canadian context.

In a recent systematic review on future planning for families of individuals with IDD, Lee and Burke (2020) found that most families did not have concrete future plans. The authors found several barriers to future planning, such as emotional demands, inertia, limited information and communication between family members, changing support needs, conflicts between individuals with IDD and their family members, and challenges for siblings balancing their own lives. Additionally, systemic barriers including lack of professionals, options, resources, funding and challenges navigating the formal service systems, also contributed to limited future planning. When considering support’s interface with formal future planning, it is important to consider that for persons experiencing social isolation, those persons who are closest to them may not be able to serve as a representative in the absence of natural supporters due to conflict of interest from being in a paid relationship. Future research might explore how to foster and engage natural support networks in particular for those experiencing social isolation.

Tomasa and Williamson (2021) indicate that person-centred future planning is important for individuals with various disabilities, where the individual should have “a central role in creating a team or network of individuals that support their desire to engage in the community and live as independently as possible” (p. 125). Again, this is where integration of formal and natural supports can optimize outcomes for individuals with disabilities and their families. For example, one of PLAN’s goals is to ensure peace-of-mind to families by developing future plans; this involves providing information, workshops and legal support to families (PLAN, 2018). Further research is needed, specifically in a Canadian context, to explore how to support families and prioritize future planning. There is a wealth of experience and knowledge from families about planning and how to effectively transition care and decision making supports from a parent to another family member or network member; and so much of this knowledge has yet to be formally studied or documented.

Lack of Diverse Perspectives

Equally as interesting as what we found in this scoping review is what we did not find. In addition to minimal information about the role of natural supports in future planning, our review also demonstrated a lack of diversity of populations and perspectives on natural support. Despite a broad search strategy, we were disappointed to find limited published literature on the nature and role of natural support for individuals with disabilities in Canada. In particular, none of the included studies explicitly discussed the particular needs or role of natural support for people from Indigenous, rural, LGBTQIA+ or racial and ethnic minority communities. This lack of representation of diverse perspectives is concerning, as specific communities may have very different approaches and values related to natural support, which could deeply benefit and inform the enablement and flourishing of natural supports in the Canadian context. In fact, Indigenous communities have been providing nurturing natural support systems for centuries – this is not ‘innovative’ or ‘novel’. Stienstra et al. (2018) described the mixed experiences of Canadian Indigenous women with disabilities, where some were isolated from family and friends (often in order to access other formal, colonial services), but others experienced inclusion and natural support; “There are very real tensions for Indigenous women with disabilities as a result of Indigenous relational ontologies that focus on inclusion and the effects and implications of colonial practices together with a medical model of disability… that have eroded their place and value as integral members of society” (p. 1401). A recent review on Indigenous community-based social care models found that, in contrast to dominant white populations, “family caregiving is central to many Indigenous models … [but] several Indigenous models integrate family care within disability services through various forms of support to caregivers, rather than imposing distinctions between formal and informal, non-remunerated caregiving” (Puszka et al., 2022, p. 3727).

Thus, we caution that the results of our review are not representative of the diverse experiences and roles of natural support across Canada, and can not be generalizable to all Canadian communities. Rather, this review should be seen as a call to finance and otherwise enable further explorations of natural support from Indigenous, rural, LGBTQIA+ or racial and ethnic minority communities, ideally by researchers who identify with these communities. In order to develop government policy and provide greater recognition and support for natural supporters, it is important to consider different perspectives and learn from those with different models and deep expertise in how to provide natural, loving support in the community

Tensions between Formal and Natural Supports

Though dependent on the nature and extent of impairment and disability, persons with disabilities often require a more intensive natural support approach, which can lead to significant pressures and challenges for natural supporters (Naganathan et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2019). This review highlighted that support provider burnout is detrimental to flourishing natural care, and can also induce feelings of guilt both for support recipients and providers. Currently, the Canada Health Act seeks to ensure that all Canadians have free access to basic medical services; however, many additional supports required by individuals with disabilities are not covered under the Act, such as Home Care which supports individuals who are unable to manage independently at home (Yakerson, 2019). Hence, as formal services become increasingly privatized in Canada, the responsibility of care falls heavily on unpaid support from family, friends, and communities, and carers often lack recognition or support themselves (Alberio, 2018; Barken, 2017; Yakerson, 2019). Although natural support can decrease service expenditure, Friedman (2021) cautions that this should not be a reason to replace formal supports, and more funding is needed to provide formal services to individuals with disabilities and their families. The requirement of being fully responsible for care cannot fall solely on families and other natural supporters who also need support and respite to flourish (Fullana et al., 2020; Reynolds et al., 2018).

Accordingly, we recommend that future research explores how national and provincial policy can be appropriately designed to support natural supports and enable the best balance of both formal and natural supports, as determined by the person with the disability. Researchers have highlighted how both formal and natural support play important roles in sustainable care provision (Peckham et al., 2021; Law et al. 2021), and we would argue that often natural supports are not given the same importance (in terms of legitimacy, funding, value) as formal supports. Overall, we suggest that Canadian policy must better reflect the vital role that natural supports provide to Canadians with disabilities, and thus better accommodate the time, financial, and emotional resources necessary to build and maintain relationships and community networks and to provide support to loved ones.

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations which should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the articles included were original sources published in English, thus we may have missed important information written in other languages. Second, while the research in our review was conducted in different geographical locations across the country, we are missing the perspectives of Canadian Indigenous peoples, those who have immigrated to Canada, and residents of Canada’s northern territories/regions. Moreover, community partner co-authors on this study indicate a depth and breadth of knowledge and practice around natural supports that has not yet been incorporated in academic literature[1] and these could be incorporated to inform future studies. This lack of diversity limits our ability to truly see a clear picture of natural supports in a Canadian context, and indicates that the picture presently offered by empirical, peer-reviewed literature is incomplete, and lacking true reflection of national experiences or expertise. Nevertheless, we see this scoping review as an initial assessment of what is currently featured in the literature and a call to action for more research – particularly implemented and informed by those with deep lived experience in natural support in all its forms.

Conclusion

Support is vital to the wellbeing of individuals with disabilities in many different life domains. Understanding the types of support that are accessed and utilized most frequently is crucial to ensure recognition of natural support networks and their contribution to the lives of those with disabilities. This scoping review demonstrates that natural support networks are invaluable, but supporters need support too; appropriate integration of formal and natural supports can enable flourishing for individuals with disabilities and their families. These findings are important to consider when looking at where funding and services are being directed in Canada, as well as policy surrounding care and resources for Canadians with disabilities. Future research is needed to explore support networks in remote and understudied regions in Canada to include the perspectives of underrepresented communities to better capture the experiences of Canadians with disabilities.

Endnotes

References

- Alberio, M. (2018). Supporting carers in a remote region of Quebec, Canada: How much space for social innovation? International Journal of Care & Caring, 2(2), 197-214.

- Araten-Bergman, T., & Bigby, C. (2022). Forming and supporting circles of support for people with intellectual disabilities – a comparative case analysis. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 47(2), 177–189.

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32.

- Bailey, K. M., Frost, K. M., Casagrande, K., & Ingersoll, B. (2020). The relationship between social experience and subjective well-being in autistic college students: A mixed methods study. Autism, 24(5), 1081-1092.

- Barken, R. (2017). Reconciling tensions: Needing formal and family/friend care but feeling like a burden. Canadian Journal on Aging, 36(1), 81-96.

- *Berry, S. J., & Domene, J. F. (2015). Supporting postsecondary students with sensory or mobility impairments in reaching their career aspirations. Career Development & Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 38(2), 78-88.

- Bigby, C. (2008). Known well by no-one: Trends in the informal social networks of middle-aged and older people with intellectual disability five years after moving to the community. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 33(2), 148-157.

- Bigby, C., Whiteside, M., & Douglas, J. (2019). Providing support for decision making to adults with intellectual disability: Perspectives of family members and workers in disability support services. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 44(4), 396-409.

- Burke, M., Arnold, C., & Owen, A. (2018). Identifying the correlates and barriers of future planning among parents of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities, 56(2), 90-100.

- *Casey, R., & Stone, S. D. (2010). Aging with long-term physical impairments: The significance of social support. Canadian Journal on Aging, 29(3), 349-359.

- Donelly, M., Hillman, A., Stancliffe, R. J., Knox, M., Whitaker, L., & Parmenter, T. R. (2010). The role of informal networks in providing effective work opportunities for people with an intellectual disability. Work, 36(2), 227-237.

- Duggan, C., & Linehan, C. (2013). The role of 'natural supports' in promoting independent living for people with disabilities; A review of existing literature. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(3), 199-207.

- *Friesen, M. N., Krassikouva-Enns, O., Ringaert, L., & Isfeld, H. (2010). Community support systems for farmers who live with disability. Journal of Agromedicine, 15(2), 166-174.

- Friedman, C. (2021). Natural supports: The impact on people with intellectual and developmental disabilities' quality of life and service expenditures. Journal of Family Social Work, 24(2), 118-135.

- Fullana, J., Pallisera, M., Vila, M., Valls, M. J., & Diaz-Garolera, G. (2020). Intellectual disability and independent living: Professionals' views via a Delphi study. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 24(4), 433-447.

- *Heifetz, M., Brown, H. K., Chacra, M. A., Tint, A., Vigod, S., Bluestein, D., & Lunsky, Y. (2019). Mental health challenges and resilience among mothers with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Disability & Health Journal, 12(4), 602-607.

- Hillman, A., Donelly, M., Dew, A., Stancliffe, R. J., Whitaker, L., Knox, M., Shelley, K., & Parmenter, T. R. (2013). The dynamics of support over time in the intentional support networks of nine people with intellectual disability. Disability & Society, 28(7), 922-936.

- Hillman, A., Donelly, M., Whitaker, L., Dew, A., Stancliffe, R. J., Knox, M., Shelley, K., & Parmenter, T. R. (2012). Experiencing rights within positive, person-centred support networks of people with intellectual disability in Australia. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(11), 1065-1075.

- Hughes, R. P., Redley, M., & Ring, H. (2011). Friendship and adults with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities and English disability policy. Journal of Policy & Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 8(3), 197-206.

- Kaley, A., Donnelly, J. P., Donnelly, L., Humphrey, S., Reilly, S., Macpherson, H., Hail, E., & Power, A. (2022). Researching belonging with people with learning disabilities: Self‐building active community lives in the context of personalisation. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 50(3), 307-320

- *Keating, N., & Dosman, D. (2009). Social capital and the care networks of frail seniors. Canadian Review of Sociology, 46(4), 301-318.

- Kelley, K. R., & Westling, D. L. (2013). A focus on natural supports in postsecondary education for students with intellectual disabilities at Western Carolina University. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 38(1), 67-76.

- *Khan, M., Brown, H. K., Lunsky, Y., Welsh, K., Havercamp, S. M., Proulx, L., & Tarasoff, L. A. (2021). A socio-ecological approach to understanding the perinatal care experiences of people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities in Ontario, Canada. Women's Health Issues, 31(6), 550-559.

- *King, G., Willoughby, C., Specht, J. A., & Brown, E. (2006). Social support processes and the adaptation of individuals with chronic disabilities. Qualitative Health Research, 16(7), 902-925.

- Knox, L., Douglas, J. M., & Bigby, C. (2016). Becoming a decision-making supporter for someone with acquired cognitive disability following traumatic brain injury. Research & Practice in Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities, 3(1), 12-21.

- *LaPierre, T. A., & Keating, N. (2013). Characteristics and contributions of non-kin carers of older people: A closer look at friends and neighbours. Ageing & Society, 33(8), 1442-1468.

- Law, S., Ormel, I., Babinski, S., Kuluski, K., & Quesnel-Vallée, A. (2021). “Caregiving is like on the job training but nobody has the manual”: Canadian caregivers’ perceptions of their roles within the healthcare system. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 404.

- Lee, C. e., & Burke, M. M. (2020). Future planning among families of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Policy & Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 17(2), 94-107.

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69.

- Lindblad, B.-M., Holritz-Rasmussen, B., & Sandman, P.-O. (2007). A life enriching togetherness - Meanings of informal support when being a parent of a child with disability. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 21(2), 238-246.

- *McConnell, D., More, R., Pacheco, L., Aunos, M., Hahn, L., & Feldman, M. (2022). Childhood experience, family support and parenting by people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 47(2), 152-164.

- *Naganathan, G., Kuluski, K., Gill, A., Jaakkimainen, L., Upshur, R., & Wodchis, W. P. (2016). Perceived value of support for older adults coping with multi-morbidity: Patient, informal care-giver and family physician perspectives. Ageing & Society, 36(9), 1891-1914.

- Peckham, A., Williams, P., Denton, M., Berta, W., & Kuluski, K. (2021). "It's more than just needing money": The value of supporting networks of care. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 33(3), 201-221.

- Pallisera, M., Fullana, J. N., Vilà, M., Diaz-Garolera, G., Puyalto, C., & Rey, A. (2022). Social networks and personal support from the perspective of young people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Youth Studies, 25(7), 913-930.

- *Petner-Arrey, J., Howell-Moneta, A., & Lysaght, R. (2016). Facilitating employment opportunities for adults with intellectual and developmental disability through parents and social networks. Disability & Rehabilitation, 38(8), 789-795.

- PLAN (2018). Planning for a Good Life: Moving from Unprepared to Peace of Mind. Facilitator's Guide. Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network. Vancouver.

- PLAN (2023). Mission, vision & values. Retrieved from: https://plan.ca/about/mission/

- *Potvin, L. A., Brown, H. K., & Cobigo, V. (2016). Social support received by women with intellectual and developmental disabilities during pregnancy and childbirth: An exploratory qualitative study. Midwifery, 37, 57-64.

- posAbilities (2018). posAbilities’ Strategic Plan 2018–2021. Retrieved from: https://www.posabilities.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2018-2021-posAbilities-Strategic-Plan.pdf

- Puszka, S., Walsh, C., Markham, F., Barney, J., Yap, M., & Dreise, T. (2022). Community‐based social care models for indigenous people with disability: A scoping review of scholarly and policy literature. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), 3716-3732.

- Reynolds, M. C., Palmer, S. B., & Gotto, G. S. (2018). Reconceptualizing natural supports for people with disabilities and their families. In M. M. Burke (Ed.), International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities (pp. 177-209). Elsevier.

- Roll, A. E., & Bowers, B. J. (2019). Building and connecting: Family strategies for developing social support networks for adults with down syndrome. Journal of Family Nursing, 25(1), 128-151.

- *Rudman, D. L., Gold, D., McGrath, C., Zuvela, B., Spafford, M. M., & Renwick, R. (2016). “Why would I want to go out?”: Age-related vision loss and social participation. Canadian Journal on Aging, 35(4), 465-478.

- *Sallafranque-St-Louis, F., & Normand, C. L. (2017). From solitude to solicitation: How people with intellectual disability or autism spectrum disorder use the internet. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 11(1).

- Sanderson, K. A., Burke, M. M., Urbano, R. C., Arnold, C. K., & Hodapp, R. M. (2017). Who helps? Characteristics and correlates of informal supporters to adults with disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities, 122(6), 492-510.

- Shelley, K., Donelly, M., Hillman, A., Dew, A., Whitaker, L., Stancliffe, R. J., Knox, M., & Parmenter, T. (2018). How the personal support networks of people with intellectual disability promote participation and engagement. Journal of Social Inclusion, 9(1), 37-57.

- Simplican, S. C., Leader, G., Kosciulek, J., & Leahy, M. (2015). Defining social inclusion of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: An ecological model of social networks and community participation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 18-29.

- Stienstra, D., Baikie, G., & Manning, S. M. (2018). ‘My granddaughter doesn’t know she has disabilities and we are not going to tell her’: Navigating intersections of Indigenousness, disability and gender in Labrador. Disability & the Global South, 5(2), 1385-1406.

- *Taylor, W. D., Cobigo, V., & Ouellette‐Kuntz, H. (2019). A family systems perspective on supporting self‐determination in young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(5), 1116-1128.

- Tobin, M. C., Drager, K. D. R., & Richardson, L. F. (2014). A systematic review of social participation for adults with autism spectrum disorders: Support, social functioning, and quality of life. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(3), 214-229.

- Tomasa, L. T., & Williamson, H. J. (2021). Belonging and inclusion: Supporting individuals and families throughout the future planning process. In J. L. Jones & K. L. Gallus (Eds.), Belonging and Resilience in Individuals with Developmental Disabilities: Emerging Issues in Family and Individual Resilience (pp. 119-140). Springer, Cham.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., Godfrey, C. M., Macdonald, M. T., Langlois, E. V., Soares-Weiser, K., Moriarty, J., Clifford, T., Tunçalp, Ö., & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467-473.

- United Nations (UN, 2007). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Ch_IV_15.pdf

- Vela Canada (2022). About Vela Canada. Retrieved from: https://velacanada.org/about/about-us/

- White, K., & Mackenzie, L. (2015). Strategies used by older women with intellectual disability to create and maintain their social networks: An exploratory qualitative study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 78(10), 630-639.

- Yakerson, A. (2019). Home care in Ontario: Perspectives on equity. International Journal of Health Services, 49(2), 260-272.

Appendix

| First Author (Year) | Title | Study Population (Age) | Type of Disability | # of Participants | Study Design | Aim of Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berry (2015) | Supporting Postsecondary Students with Sensory or Mobility Impairments in Reaching their Career Aspirations | Postsecondary students (ages 19-32 years) | Various – hearing, mobility, speech, and visual impairments | 15 | Qualitative (interviews) | Explore (a) what kinds of supports were repeatedly identified as important, (b) what types of barriers each kind of support helps with, and (c) why/how each kind of support was beneficial to participants. |

| Casey (2010) | Aging with Long-Term Physical Impairments: The significance of Social Support | Community-dwelling adults (ages 50-65 years) | Various - longer than 15 years (MS, RA, MD, Legg-Calvé Perthes Syndrome, PKD) | 8 | Qualitative (interviews) | Examine the living situations and access to social support for community-dwelling adults. |

| Friesen (2010) | Community Support Systems for Farmers Who Live with Disability | Farmers; (ages 47-75 years); service providers | Various – long term impairments as a result of injury | 28 (11 farmers, 17 service providers) | Qualitative (interviews and focus groups) | Examine barriers and facilitators of returning to work after an injury or acquired disability, and identify community supports (formal and informal) needed and available to farmers. |

| Heifetz (2019) | Mental Health Challenges and Resilience Among Mothers with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities | Women with a previous livebirth (average age 35.3 years) | IDD | 12 | Qualitative (focus groups) | Identify key risk, protective, and resilience factors that affect mental health among mothers with IDD. |

| Keating (2009) | Social Capital and the Care Networks of Frail Seniors | Older adults receiving assistance from family/friends (ages 65+) | Various – long term impairment | 2407 | Quantitative (telephone survey) | Explore the types of care networks of older adults and how they differ in structural characteristics, and how care-potential is actualized. |

| Khan (2021) | A Socio-Ecological Approach to Understanding the Perinatal Care Experiences of People with Intellectual and/or Developmental Disabilities in Ontario, Canada | Women who had given birth in the past 5 years (ages 18+) | IDD | 10 | Qualitative (interviews) | Examine factors that shape the perinatal care experiences of people with IDD using the Socio-Ecological Model. |

| King (2006) | Social Support Processes and the Adaptation of Individuals with Chronic Disabilities | Adults (ages 30-50 years) | Various – ADHD, CP, Spina Bifida | 15 | Qualitative (interviews) | Understand the experience and meaning of social support and its role in adaptation over time. |

| Lapierre (2013) | Characteristics and Contributions of Non-Kin Carers of Older People: A Closer Look at Friends and Neighbours | Non-kin caregivers (Friends or neighbours) providing informal assistance to adults aged 65+ | Various – long term impairments | 324 | Quantitative (telephone survey) | Explore the characteristics of non-kin carers, the types of care tasks, amount and duration of care by non-kin providers, and the interpersonal and socio-demographic factors that predict the amount of time spent providing care. |

| McConnell (2022) | Childhood Experience, Family Support and Parenting by People with Intellectual Disability | Parents (average age 38.87) | ID | 91 | Mixed Methods (structured interviews with scales and open-ended questions) | Understand the biographical and relational context of parenting for people with intellectual disability, including connections between parents’ childhood experiences, perceived social support and interference, and assessments of their own parenting. |

| Naganathan (2016) | Perceived Value of Support for Older Adults Coping with Multi-Morbidity: Patient, Informal Care-Giver and Family Physician Perspectives | Older adults (ages 65+) caregivers, physicians | Various – two or more long-term conditions | 58 (27 older adult-caregiver pairs, 4 physicians) | Qualitative (interviews) | Explore how the perceived value of various formal and informal supports influences the role of social support in the lives of older adults. |

| Petner-Arrey (2016) | Facilitating Employment Opportunities for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disability through Parents and Social Networks | Adults (ages 21-54) and their families or caregivers as proxies | IDD | 114 | Qualitative (interviews) | Understand the experiences of people with IDD gaining and keeping productivity roles. |

| Potvin (2016) | Social Support Received by Women with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities During Pregnancy and Childbirth: An Exploratory Qualitative Study | Women who have had a live pregnancy in the last 5 years (ages 18+) | ID | 4 | Qualitative (interviews) | Explore the structure, functions, and perceived quality of social support received by women with IDD during pregnancy and childbirth. |

| Rudman (2016) | "Why Would I Want to Go Out?": Age-Related Vision Loss and Social Participation | Older adults (ages 65+) | ARVL | 21 | Qualitative (interviews, audio diaries, life space maps) | Examine experiences of rehabilitation and everyday life among older adults with ARVL, specifically to understand the process of social participation. |

| Sallafranque-St-Louis (2017) | From Solitude to Solicitation: How People with Intellectual Disability or Autism Spectrum Disorder use the Internet | Adults (ages 19-40) | Mild ID, ASD | 8 | Mixed Methods (Questionnaire and qualitative interviews) | Understand internet use and experiences of young adults with ID or ASD. |

| Taylor (2019) | A Family Systems Perspective on Supporting Self-Determination in Young Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities | Families with adult family members with IDD (ages 18-30) | IDD | 2 families | Qualitative (Case Study) | Explore the way that families support self-determination in young adults with IDD during life transitions. |