Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on IBPOC with Disabilities and their Networks: A Scoping Review

Impacts de la pandémie de COVID-19 sur les personnes autochtones, noires et de couleur (PANDC) handicapées et leurs réseaux : une revue de la portée

Corresponding Author:

Ramona H. Sharma

Canadian Institute for Inclusion and Citizenship, School of Social Work, University of British Columbia (Okanagan), Kelowna, BC, Canada

1147 Research Road, University of British Columbia Okanagan, Kelowna, BC Canada, V1V 1V7

ramona [dot] sharma [at] ubc [dot] ca

Alexander Fuhrmann

Okanagan School of Business, Okanagan College, Kelowna, BC, Canada

alex [dot] fuhrmann [at] myokanagan [dot] bc [dot] ca

Brettley Mason

Brett Mason Counselling, Vancouver Island, BC, Canada

brettmasoncounselling [at] gmail [dot] com

Clayton March

School of Social Work, University of British Columbia (Okanagan), Kelowna, BC, Canada

marchclayton1 [at] gmail [dot] com

Rachelle Hole

Canadian Institute for Inclusion and Citizenship, School of Social Work, University of British Columbia (Okanagan), Kelowna, BC, Canada

rachelle [dot] hole [at] ubc [dot] ca

Timothy Stainton

Canadian Institute for Inclusion and Citizenship, School of Social Work, University of British Columbia (Vancouver), Vancouver, BC, Canada

timothy [dot] stainton [at] ubc [dot] ca

Abstract

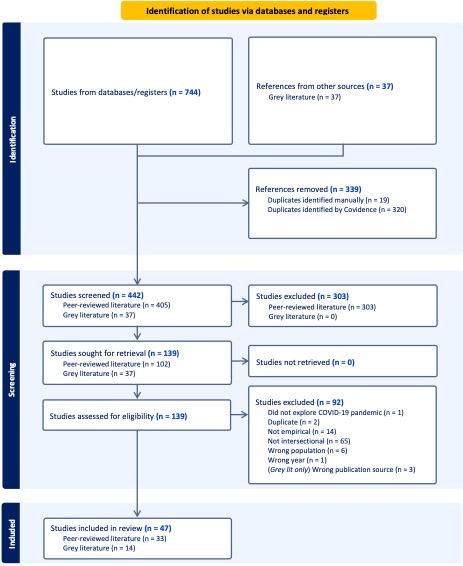

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted Indigenous, Black, and People of Colour (IBPOC) with disabilities, yet intersectional effects remain underexplored. As such, following guidelines from PRISMA and Arksey and O’Malley, this 2024 scoping review examined 47 publications (33 peer-reviewed articles and 14 grey literature reports) from an initial pool of 744 publications to explore the impact of COVID-19 on minority-status IBPOC populations with disabilities and their networks. Covering diverse global contexts, including the USA, Canada, the UK, Finland, the Netherlands, Nepal, among other countries, the review identified varied impacts such as occupational disruptions, barriers to healthcare and education, limited access to resources, adverse effects on families and children, and significant psychosocial challenges. Additionally, findings revealed critical gaps in knowledge, including the predominance of US-based studies, insufficient exploration of intersectional identities beyond binary gender, and a lack of disaggregated data on race and disability. These findings underscore the urgent need for intersectional research methodologies and the development of inclusive public health policies tailored to the unique needs of IBPOC with disabilities. Addressing these gaps will enhance resilience and equity in global health responses, ensuring that marginalized populations receive the support and resources necessary during and after pandemics.

Résumé

La pandémie de COVID-19 a eu des répercussions disproportionnées sur les personnes autochtones, noires et de couleur (PANDC) handicapées, bien que les effets intersectionnels demeurent encore largement sous-explorés. En suivant les lignes directrices PRISMA et le cadre méthodologique d’Arksey et O’Malley, cette revue de la portée réalisée en 2024 a analysé 47 publications, dont 33 articles évalués par des pairs et 14 rapports issus de la littérature grise, sélectionnées à partir d’un corpus initial de 744 documents. L’objectif était d’examiner les impacts de la COVID-19 sur les populations PANDC handicapées minorisées et leurs réseaux. Couvrant une diversité de contextes mondiaux, notamment les États-Unis, le Canada, le Royaume-Uni, la Finlande, les Pays-Bas, le Népal, la revue a mis en lumière une série d’impacts : perturbations professionnelles, obstacles à l’accès aux soins de santé et à l’éducation, accès restreint aux ressources, effets délétères sur les familles et les enfants, ainsi que des défis psychosociaux majeurs. Les résultats ont également révélé des lacunes critiques dans les connaissances, telles que la prédominance des études centrées sur les États-Unis, une exploration limitée des identités intersectionnelles au-delà du genre binaire, et l’absence de données désagrégées sur la race et le handicap. Ces constats soulignent l’urgence de concevoir des méthodologies de recherche intersectionnelles et de mettre en œuvre des politiques de santé publique inclusives, répondant aux besoins spécifiques des PANDC handicapées. Combler ces lacunes contribuera à renforcer la résilience et l’équité dans les réponses sanitaires à l’échelle mondiale, en garantissant que les populations marginalisées bénéficient du soutien et des ressources nécessaires, tant pendant qu’après les pandémies.

Keywords: IBPOC; COVID-19; pandemic; disabilities; scoping review; intersectional disability

Mots-clés : PANDC; COVID-19; pandémie; handicap; revue de la portée; handicap intersectionnel

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic did not affect everyone equally (Barbu et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020b). The ongoing effects of the pandemic, e.g., strained medical care and resource allocation constraints, are noted to have been further exacerbated for specific populations due to existing societal inequities related to disability, gender, minority race, socioeconomic status, and geographic location (DeJong et al., 2020; Evans et al., 2020). Examples of such inequities include disabled individuals needing to defer medical treatment for serious medical conditions unrelated to the coronavirus thereby leading to death and exacerbation of medical complications, women facing greater intimate partner violence (IPV) during lockdowns due to being trapped indoors with their abusers and being unable to connect with supports, and minority-status Indigenous, Black, and People of Colour (IBPOC)[1] communities being unable to receive culturally appropriate support and treatment due to preexisting systemic racism in healthcare (DeJong et al., 2020; Evans et al., 2020).

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, both IBPOC and disabled populations independently faced systemic barriers that compromised their health and well-being. In countries such as Canada, the US, Australia, India, and Nepal, post-colonial inequities have historically been linked to unmet health needs, reluctance to seek care, increased mortality, and the devaluation of traditional knowledge and practices, particularly through discrimination against minority Indigenous peoples within healthcare systems (Cameron et al., 2014; Turpel-Lafond, 2020; Kitching et al., 2020; Nader et al., 2017). As a result, worldwide, Indigenous populations often receive inadequate health services compared to non-Indigenous groups (Nader et al., 2017).

Non-Indigenous ethnic minorities also face systemic challenges due to institutional barriers like gentrification, redlining, systemic and structural racism, and disproportionately low socioeconomic status, which hinder equitable access to healthcare and exacerbate disparities (Charron-Chénier et al., 2018; Henning-Smith et al., 2019). The US and Canada are prevalent examples of this, where Black and Latinx communities experience higher disease exposure, greater mortality rates, reduced outpatient care, and limited access to essential healthcare services (Crouse Quinn et al., 2011; Saadi et al., 2019).

Separately, persons with disabilities encounter numerous systemic barriers to healthcare, such as inaccessible clinic spaces, lack of disability-sensitive training among healthcare providers, inadequate accommodation policies, and challenges in navigating complex healthcare systems (Hwang & Smith, 2023). These systemic issues often lead to delays or avoidance of care, resulting in disproportionately high mortality rates, as evidenced by elevated COVID-related deaths among persons with disabilities (Barbu et al., 2020; Greenwood et al., 2014; Kurre, 2014; Mirza et al., 2014; Pace et al., 2011; Williamson et al., 2017).

The COVID-19 pandemic has likely worsened these pre-existing disparities, intensifying attitudinal barriers (e.g., racism, ableism, sexism, and stigma), institutional challenges (e.g., inaccessible health information and discriminatory legislation), and environmental obstacles (e.g., inaccessible facilities and overcrowding). Addressing these inequities is critical for post-pandemic recovery and the creation of inclusive, equitable healthcare systems.

Existing literature highlights the intersectional challenges of minority IBPOC identity and disability. For instance, disabled refugees face barriers such as limited access to medical insurance, language and communication difficulties, and bureaucratic complexities within dominant health systems (Mirza et al., 2014). Similarly, IBPOC individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are significantly more likely than their White counterparts with IDD to rate their health as 'poor' or 'fair' (Magaña et al., 2016). Despite these observations, there is limited research on the intersectional impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on minority-status IBPOC with disabilities. However, understanding the acute and ongoing impacts of COVID-19 on persons with disabilities within IBPOC communities is vital for identifying and addressing intersecting forms of discrimination, health disparities, and cultural nuances in a post-pandemic landscape. Such knowledge will inform targeted interventions, promote cultural competence, and support advocacy efforts to address the unique challenges faced by disabled IBPOC individuals during and since the pandemic.

As such, the present study conducts a comprehensive scoping review to explore the intersectional impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on minority-status IBPOC individuals with disabilities and their support networks. For the purpose of this review, disability is defined as “long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder full and effective participation in society” (United Nations, n.d.), and minority status is defined as “a category of people who experience relative disadvantage in relation to members of a dominant social group” (Song, 2020). Recognizing the global significance of this issue, this review examined trends from any country where IBPOC populations have historically faced systemic marginalization and continue to hold minority status (e.g., the Dalit population in India); it explores how disability within these groups intersects with systemic inequities, offering a broad and inclusive perspective on the compounded challenges they experience. Specifically, this study sought to answer the following question: “what are the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on minority-status IBPOC with disabilities and their networks (e.g., family members, caregivers, etc.)?”

Methods

The present scoping review was conducted in November 2024 following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018) and the framework outlined by Arksey & O'Malley (2005). The primary objective was to systematically map the existing peer-reviewed and grey literature on the impact of COVID-19 on disabled IBPOC (Indigenous, Black, People of Colour) populations to inform policymakers and social justice advocates for evidence-based decision-making.

Search Strategy

All search strategies were collaboratively developed by all authors in conjunction with a University of British Columbia (UBC) librarian, ensuring comprehensive coverage of relevant terms and concepts. The peer-reviewed search, conducted by three authors (RS, AF, BM) encompassed: (1) disability-related terms, such as "disab*," "IDD," "autism," and "neurodiversity;” (2) IBPOC-related terms, including "IBPOC," "person of colour," "racial*," "ethnic*," "Black," "Hispanic," "Latinx," "Asian," "migrant," "immigra*," "newcomer*," "refugee," "mixed-race," and "biracial*,” and (3) COVID-19-related terms, like "coronavirus," "COVID-19," and "pandemic". A complete search strategy is detailed in Appendix A. Peer-reviewed, English-language articles published between 2019 and 2024 were identified through systematic searches of the following databases: CINAHL, PsycInfo, Medline, Web of Science Core Collection, Business Source Ultimate, Education Source, ERIC, PubMed, Social Services Abstracts, EMBASE, and Academic Search Premier. These databases were selected for their relevance to social sciences, interdisciplinary research, and studies examining disability, IBPOC, and public health (Beaudry & Miller, 2016; Hughes & Sharp, 2021). The search start date of 2019 was selected to capture early surveillance data and pre-print literature, as the first known cases of COVID-19 were reported in December 2019 in Wuhan, China (World Health Organization, 2020a). This timeframe allowed for the inclusion of early documentation of the immediate impacts of SARS-CoV-2 prior to the World Health Organization’s official pandemic declaration in March 2020. A total of 744 peer-reviewed articles were retrieved. After exporting to the online data management system Covidence, 339 duplicate articles were removed, leaving 405 peer-reviewed articles for title and abstract screening.

In addition to peer-reviewed sources, a grey literature search was undertaken to capture reports, policy documents, and other non-academic publications from IBPOC- and disability-focused service providers and advocacy organizations. This search aimed to mitigate publication bias and enhance the comprehensiveness of the review, as well as allow for greater inclusion of research and perspectives from academic institutions and organizations in the Global South, which are often excluded from or underrepresented in Global North publication systems (Abimbola, 2023). Utilizing a similar strategy, the grey literature search employed simplified terms: “disability” AND “race” AND “covid*”. A Google search was conducted by three authors (RS, AF, CM) for English-language publications from 2019 to 2024, yielding approximately 35,800,000 results. Given the volume and heterogeneity of search returns, including duplicates, inaccessible sources, and irrelevant content with respect to study aims, a full census was not feasible; thus, due to the impracticality of reviewing all results, a data saturation approach was adopted where relevant documents were saved, terminating the search once no new relevant documents were identified (Fusch & Ness, 2015).

Study Selection and Screening

Four authors (RS, AF, BM, CM) independently screened all articles against pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Peer-reviewed studies were included if they empirically addressed the intersection of COVID-19, disability, and minority-status IBPOC, and were published in English. Studies were excluded if they did not address or discuss ethnic minorities, the COVID-19 pandemic, or disability; if they failed to explore the intersectionality between these elements; if they were published before 2019; if they utilized non-empirical study designs such as literature reviews, opinion pieces, or editorials, or if they only provided theoretical insights without documenting empirical and/or experiential effects of the pandemic on the selected population or their networks; and if they were not published in English. For grey literature, in addition to applying the exclusion criteria for peer-reviewed literature and the data saturation approach, publications were excluded if they were not published by government agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), health authorities, or academic institutions.

Following this screening, 102 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, with 33 peer-reviewed articles meeting all inclusion criteria for data extraction. 37 grey literature articles were initially screened for relevance, with 14 publications meeting the inclusion criteria. Lastly, we also screened the citations of all included publications for additional relevant sources: no new sources were found. Figure 1 below depicts the study selection process.

Figure 1

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data extraction was performed independently with discussion by four authors (RS, AF, BM, CM) using structured data extraction forms developed in Google Sheets. Extracted data from both peer-reviewed and grey literature encompassed author or organization, year and location of publication, study location, population characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, country of origin, type of disability), definition of disability, study design and methodology, sample size, data collection methods, and main findings related to the impact of COVID-19 on disabled, minority-status IBPOC and their networks.

Extracted data were synthesized by two authors (RS and AF) using thematic narrative analysis, facilitating the identification and categorization of key themes and subthemes related to the intersectional impacts of COVID-19 on disabled IBPOC. This process involved iterative discussions and collaborative refinement to ensure a thorough understanding of the data and the development of a nuanced framework for interpreting the findings. Given the scoping nature of this review, a formal quality assessment of included studies was not conducted, as the primary objective was to map the breadth of existing literature rather than evaluate the methodological rigor of individual studies (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005).

Findings

This scoping review examined 47 publications, including 33 peer-reviewed articles and 14 grey literature reports. Regarding peer-reviewed articles, 29 were from the United States, 1 from the UK, 1 from the Netherlands, 1 from Finland, and 1 from Nepal. Among them, 19 utilized qualitative methods (sample sizes ranging from 1 to 283), 8 were quantitative (sample sizes from 156 to 114,229), and 6 employed mixed-methods designs (sample sizes from 25 to 8,828). Across articles, 28 explicitly focused on IBPOC communities as wholes or examined specific racial/ethnic identities such as Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Indigenous/Native American, Asian, or immigrant communities. Of these, 2 exclusively studied Indigenous or Native American experiences (e.g., rural reservation communities in the USA or Indigenous peoples in Nepal), 3 concentrated exclusively on Latinx families or caregivers, and 1 each focused solely on Black individuals, Korean American individuals, both Black and Latinx participants, respectively. Meanwhile, 4 studies used broader terms like “racial and ethnic minority groups” or “communities of colour.” Regarding gender and age, 6 publications concentrated specifically on women’s or mothers’ experiences, while 12 explicitly examined children or students with disabilities (some overlapping with the women-focused studies). 5 articles targeted older adults, and 14 focused on either mixed-age adult populations or did not specify age.

Grey literature comprised of 10 studies focused solely on findings from individual countries (4 publications from Canada, 2 from Nepal, 2 from the UK, 2 from the USA), as well as 4 studies simultaneously presenting findings from various countries (1 from various European countries (mainly UK and France), 1 from various Asian countries (Nepal, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines), and 2 spanning multiple countries worldwide (Asia, Central America, Oceania and Australia)). These sources included government and NGO websites, statistical data, advocacy reports, and commentary on pandemic-related issues. Of these, 6 focused exclusively on Indigenous communities (e.g., Indigenous peoples in Canada, Nepal, Asia, or globally), while several others examined IBPOC groups more broadly. One publication addressed both Black and Hispanic/Latinx workers, and no references focused only on Black populations. In terms of gender, 2 publications concentrated specifically on women (e.g., Indigenous women with disabilities), 1 centred on children with disabilities, 5 explored general adult populations (including workers), and the rest did not specify an age group. Detailed raw data extraction tables for both peer-reviewed and grey literature are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Across all 47 included publications, disability representation spanned a wide range of impairment types. The majority of studies (n=30) did not disaggregate results by disability type; instead, they used broad umbrella terms such as “people with disabilities”, referencing included individuals as having serious difficulty in self-care, mobility, cognition, and chronic conditions. Among studies that did report disability type, 8 focused on intellectual or developmental disabilities (IDD), 7 addressed physical or sensory impairments (e.g., cerebral palsy, spina bifida, traumatic brain injury, speech-language impairment, vision or hearing loss), 5 examined mental health–related disabilities, and 8 focused on autism (ASD). Many studies used umbrella terms like “people with disabilities,” encompassing individuals with serious difficulty in self-care, cognition, ambulation, or chronic conditions. Within studies with unspecified or mixed disability populations, specific disabilities quoted spanned ASD, IDD, speech-language impairment, visual impairment, paraplegia, spina bifida, cerebral palsy, learning disabilities, traumatic brain injury, hearing impairment, Down syndrome, and Long COVID.

Findings revealed both independent and intersectional impacts of COVID-19 on IBPOC and persons with disabilities. Disabled IBPOC faced heightened stress, mental health burdens, discrimination, and barriers to healthcare, often compounded by systemic racism, poverty, and gender disparities. Globally, disabled individuals from minority backgrounds experienced economic hardships, increased violence, and overrepresentation in high-risk areas during the pandemic, with these impacts exacerbated by pre-existing inequities (Jones et al., 2020; Chakraborty, 2020; Uldry & Leenknecht, 2021). These broad patterns emerged across four interconnected thematic categories, each described in greater detail and with examples in the following subsections: (1) occupational impacts, including overrepresentation in frontline positions and increased risks of exposure; (2) barriers to healthcare access, including facility closures, diminished virtual access, and lack of culturally appropriate resources; (3) impacts on families and children, including caregiver challenges and reductions in specialized pediatric care and education; and (4) psychosocial experiences, including poorer mental health, increased IPV, and experiences of encountering and resisting discrimination. The thematically distinct findings were found to be deeply interconnected, with each theme reciprocally influencing and intensifying the others.

Occupational Impacts: Overrepresentation in Frontline Positions and Increased Risks of Exposure

First, thirteen publications highlighted how minority-status disabled IBPOC in the United States, the United Kingdom, Nepal, and other countries faced disproportionate occupational burdens during the COVID-19 pandemic due to an increased necessity for in-person work (Asia Indigenous People’s Pact, 2020; Brooks & von Schrader, 2023; Chakraborty, 2020; Gurung, 2020; Hahmann, 2021; Millett et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2022; National Disability Institute, 2020; NIDWAN, 2021; Okonkwo, 2020; Pitts, 2020; Schall et al., 2021; Schur et al., 2021). Systemic barriers have historically restricted access to higher-paying “white-collar” occupations for disabled IBPOC, leading to overrepresentation in lower-wage, face-to-face industries such as service, hospitality, care aide, and tourism. This structural inequity left them especially vulnerable to both job losses and heightened exposure to COVID-19 during the pandemic (Schall et al., 2021; Schur et al., 2021).

Studies reported that disabled IBPOC were significantly less able to perform their jobs remotely compared to non-disabled or White counterparts, further amplifying their risks (Brooks & von Schrader, 2023; Schall et al., 2021). For instance, while 35.2% of the general population could work from home, no workers with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) in a specific study sample were afforded this opportunity (Schall et al., 2021). Disabled IBPOC women, particularly those in low-wage, non-remote roles, faced severe job losses and slower re-employment rates, deepening economic hardship (Schur et al., 2021). Nationwide data revealed that IBPOC individuals with disabilities endured a 35% rate of job loss and were largely excluded from pandemic relief efforts, further exacerbating financial insecurity (National Disability Institute, 2020).

Geographic inequities also intensified occupational disparities. Disabled Black, Asian, and Indigenous individuals were more likely to live in regions with high COVID-19 incidence compared to White persons with disabilities (Chakraborty, 2020). In the United States, counties with predominantly Black populations, representing nearly 20% of all counties, accounted for 52% of COVID-19 diagnoses and 58% of deaths, underscoring stark racial and occupational inequities (Millett et al., 2020). Further, worldwide, Indigenous women with disabilities frequently worked in feminized frontline roles, such as nursing, which exposed them to heightened infection risks (Asia Indigenous People’s Pact, 2020). Last, disabled IBPOC often faced barriers to practicing social distancing due to reliance on in-person or at-home physical assistance (Gurung, 2020).

In sum, structural barriers and occupational inequities meant that disabled IBPOC had fewer opportunities for remote work and a greater reliance on high-risk, public-facing roles, increasing their vulnerability to COVID-19 exposure and its severe consequences. This overrepresentation in frontline positions perpetuated systemic disparities, leaving disabled IBPOC disproportionately at risk of illness, hospitalization, and death throughout the pandemic (Brooks & von Schrader, 2023; Schur et al., 2021; Okonkwo, 2020).

Barriers to Healthcare Access: Facility Closures, Diminished Virtual Access, and Lack of Culturally-Appropriate Resources

Second, thirteen publications documented how disabled IBPOC, who often relied on non-emergent health services to maintain overall health, were disproportionately impacted when healthcare systems reallocated resources toward emergency responses during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bergmans et al., 2022; Uldry & Leenknecht, 2021; Hahmann, 2021; Holmes et al., 2024; Holm et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2023; Minority Rights Group, 2020; NIDWAN, 2021; Okonkwo, 2020; Pitts, 2020; Shenk et al., 2024; Umpleby et al., 2023). Service reductions resulted in the suspension or cancellation of vital programs, including screenings, specialized care, and long COVID evaluations, which caused delays in diagnoses, worsened physical health, and increased financial strain (Bergmans et al., 2022). Black and Hispanic individuals with disabilities faced particularly severe consequences due to the intersection of service reductions and preexisting economic inequities (Schur et al., 2021).

A survey of Indigenous persons with disabilities in Canada found that 51–58% reported worsening physical health during the pandemic, compared to 39–54% of non-Indigenous disabled Canadians (Hahmann, 2021). Barriers such as postponed services, reduced transportation options, and limited financial resources further constrained access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and essential care. Similar trends were observed among older Black and Hispanic disabled adults in the United States, who faced delayed COVID-19 testing and heightened health risks due to systemic inequities (Shenk et al., 2024).

In particular, the shift to telehealth created new challenges for disabled IBPOC. Poor internet connectivity, lack of technical support, and telehealth platforms that were not designed to accommodate sensory, cognitive, or linguistic needs disproportionately affected their access to care (Lee et al., 2023; Yoshida et al., 2021). Immigrant-origin individuals with disabilities faced additional hurdles, including unfamiliarity with online healthcare systems and language barriers that increased the likelihood of missed appointments (Holm et al., 2024). Providers under pandemic stress often deprioritized care for disabled IBPOC, citing insufficient training in addressing the intersection of disability, race, and ethnicity (Lee et al., 2023).

Beyond telehealth, the absence of culturally and linguistically appropriate healthcare resources further deepened disparities. In Nepal, for example, quarantine facilities and public health campaigns often failed to incorporate local languages or respect cultural norms, leaving disabled individuals particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 (NIDWAN, 2021). In Canada, Indigenous disabled individuals similarly encountered public health materials that lacked cultural competence (Okonkwo, 2020). Structural inequities were further underscored in cases where disabled IBPOC faced outright denial of care or inaccessible quarantine facilities, reflecting systemic racism and ableism (Uldry & Leenknecht, 2021; Voluntary Organisations Disability Group, 2022). For Black individuals with disabilities, intersecting racial and disability stigma also hindered access to mental health services, as many providers were unprepared to deliver culturally sensitive care (Holmes et al., 2024).

Across global contexts, disabled IBPOC described experiences of being rendered “invisible” within healthcare systems, often facing “double discrimination” due to their race and disability (Umpleby et al., 2023; Minority Rights Group, 2020). This compounded impact of facility closures, inadequate virtual care options, and insufficient cultural and linguistic adaptations left many disabled IBPOC without the essential health services they needed, exacerbating already stark inequities (Lee et al., 2022; Pitts, 2020; Yoshida et al., 2021).

Impacts on Families and Children: Caregiver Challenges and Reductions in Specialized Pediatric Care and Education

Next, children with intellectual and developmental disabilities from Indigenous, Black, newcomer, and low-income families were found to experience profound disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly impacted their families. Ten publications highlighted how the families of disabled IBPOC faced elevated caregiver stress due to pandemic-specific factors, including reduced emotional and financial support, increased social isolation, and the strain of living in close quarters, all of which contributed to heightened psychosocial stress and “cabin fever” (Alba et al., 2022; Cioè-Peña, 2022; Dababnah et al., 2021; Geuijen et al., 2021; Hong et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2023; Luna et al., 2023; Martinez & Correa-Torres, 2023; Neece et al., 2020; Rios et al., 2022). For many parents, balancing work obligations with childcare became particularly challenging as childcare services diminished and social distancing constraints compounded caregiving burdens (Neece et al., 2020; Martinez & Correa-Torres, 2023).

Overwhelmingly, changes in daily routines imposed significant stress, particularly for families supporting children with behavioural needs. Parents reported elevated stress levels as they struggled to manage these challenges (Neece et al., 2020). In Canada, the worsening physical health of Indigenous persons with disabilities, reported by 51–58% of respondents compared to 39–54% of non-Indigenous disabled Canadians, exacerbated caregiving challenges, particularly when combined with economic hardships (Hahmann, 2021). Qualitative research also revealed that many Latinx parents observed signs of emotional and mental health deterioration in their children, including boredom, irritability, restlessness, and difficulty concentrating (Neece et al., 2020). In fact, 85.7% of Latinx caregivers reported noticeable declines in their children’s emotional well-being during lockdowns (Neece et al., 2020). For families reliant on public transportation, such as many IBPOC households, fears of COVID-19 exposure and lack of private vehicles created further obstacles to accessing in-person schooling and other services (Paterson, 2020).

Globally, reductions in specialized pediatric disability care compounded these difficulties. Key resources, such as personnel, durable medical equipment, and personal protective equipment (PPE), were diverted to emergency COVID-19 responses, leading to interruptions in therapy, education, and medical care (Neece et al., 2020; Paterson, 2020). These disruptions left families of disabled IBPOC struggling to navigate increasingly scarce services and deepened preexisting inequities in healthcare and education (Asia Indigenous People’s Pact, 2020; Hahmann, 2021; Dababnah et al., 2021).

In terms of education, school closures and the transition to remote learning exacerbated existing inequities and introduced additional barriers (Aquino & Scott, 2022). Simultaneously, disruptions to specialized pediatric services, including therapies, school-based programs, and healthcare, worsened the challenges faced by caregivers. Parents reported feeling incapable of meeting the educational and developmental needs of their children without access to these essential services (Neece et al., 2020; Paterson, 2020). The pandemic’s effects were most acutely felt by Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and newcomer families, who were already grappling with systemic inequities and limited financial resources (Paterson, 2020; Running Bear et al., 2021). In rural and reservation communities, limited internet access and resource shortages further obstructed access to special education, compounding feelings of isolation and educational setbacks (Running Bear et al., 2021). Separately, for non-pediatric populations, e.g., higher education, the pandemic caused challenges in providing accommodations, maintaining engagement, and addressing the increased mental health needs of minority students with disability (Aquino & Scott, 2022). Overall, the pandemic exposed and intensified the systemic disparities faced by families of disabled IBPOC, heightening caregiving burdens while reducing access to critical resources across healthcare, education, and daily life.

Psychosocial Experiences: Poorer Mental Health, Increased Intimate Partner Violence, and Encounters/Resistance to Discrimination

Lastly, and in line with the previous, nineteen publications detailed how disabled IBPOC experienced exacerbated psychosocial challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, including heightened mental health struggles, increased exposure to violence, and encounters with systemic discrimination (Alba et al., 2022; Cioè-Peña, 2022; Dababnah et al., 2021; Geuijen et al., 2021; Gurung, 2020; Gurung, 2021; Hahmann, 2021; Holmes et al., 2024; Hong et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2023; Luna et al., 2023; Martinez & Correa-Torres, 2023; Minority Rights Group, 2020; Neece et al., 2020; NIDWAN, 2021; Reber et al., 2021; Rios et al., 2022; Suarez-Balcazar et al., 2021; Torres, 2020). Disrupted routines, prolonged social isolation, and pandemic-related stress compounded preexisting inequities, contributing to widespread anxiety, depression, and feelings of disconnection (Dodds & Maurer, 2022; Reber et al., 2021). In the United States, American Indian/Alaska Natives reported a 41% rise in stress levels, compared to a 12% rise among non-Hispanic Whites, while Black individuals with disabilities faced intersecting burdens of racism, inadequate culturally sensitive care, and intensified economic hardships (Jones et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2024).

Disabled Indigenous and racialized women bore a disproportionate share of pandemic-specific psychosocial impacts, such as balancing caregiving responsibilities with work and experiencing increased rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual assault (Hahmann, 2021; NIDWAN, 2021; Minority Rights Group, 2020). In Canada, disabled Indigenous women reported worse mental health outcomes compared to their male counterparts during the pandemic (Hahmann, 2021). Similarly, in Nepal, reports of sexual assaults and murders of disabled Indigenous women surged, with financial barriers, inaccessible shelters, and distancing measures limiting escape options and protective interventions (Gurung, 2020; NIDWAN, 2021; Minority Rights Group, 2020).

Disabled IBPOC were also subjected to overt racism, bias, and distrust in public health guidelines, further isolating them and heightening financial strain (Nvé Díaz San Francisco et al., 2023; NIDWAN, 2021; Asia Indigenous People’s Pact, 2020). Several studies reported increased risks of suicide, depression, and anxiety among disabled IBPOC, compounded by reduced access to therapies and economic challenges (Gurung, 2020; Okonkwo et al., 2020; Hahmann, 2021; Minority Rights Group, 2020). Among Latinx communities, lack of social support and income disparities were associated with worsening mental health, while experiential avoidance contributed to psychological strain (Mayorga et al., 2022; Suarez-Balcazar et al., 2021).

Despite these hardships, disabled IBPOC demonstrated resilience and resistance to systemic oppression. Community organizing shifted online, enabling greater participation in advocacy movements such as Black Lives Matter in the United States (Torres, 2020). Activists and scholars documented their pandemic experiences through storytelling, creative expression, and social media, fostering solidarity and promoting systemic change (Gurung, 2020; Torres, 2020). In Asia, disabled Indigenous women collaboratively advocated for mutual aid and disability rights, showcasing the potential for collective action during crises (Asia Indigenous People’s Pact, 2020). In one instance, a Latina mother with an invisible disability used daily drawings to document her pandemic experience, reflecting on the intersection of personal and political challenges during lockdown (Torres, 2020). In sum, disabled IBPOC faced intensified psychosocial stress, discrimination, and violence during the pandemic while simultaneously resisting and adapting to systemic inequities, demonstrating the complex intersectionality of oppression and resilience within marginalized communities.

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to examine the literature pertaining to the impacts of COVID-19 on disabled IBPOC minorities. Our findings revealed significant health and social inequities faced by this population: overrepresentation in frontline positions, increased exposure to COVID-19, economic and occupational instability, disparities in accessing healthcare and culturally relevant resources, caregiving burdens and reduced access to specialized pediatric services, exacerbated psychosocial stress, increased intimate partner violence (IPV), and encounters with systemic racism and discrimination.

Significance and Short-Term Implications

Our findings highlight the diverse and compounding factors contributing to inequitable outcomes for disabled IBPOC. These factors operate across multiple levels: at the micro or individual level (e.g., worsening mental health, financial strain), mezzo or community level (e.g., barriers to accessing healthcare in underserved areas), and macro or systemic level (e.g., structural inequities in employment and healthcare systems). The interconnected nature of these factors underscores the importance of adopting intersectional approaches to policy and program design that address the complex realities of disabled IBPOC.

The overrepresentation of disabled IBPOC in frontline occupations during the pandemic reflects systemic inequities rooted in historical exclusion from higher-paying, remote-eligible jobs. This occupational disparity not only increased exposure to COVID-19 but also deepened economic precarity, reinforcing cycles of poverty and marginalization (Brooks & von Schrader, 2023; Schur et al., 2021). Addressing these inequities requires structural changes, such as targeted workforce development programs and inclusive hiring practices, to dismantle the systemic barriers that disproportionately confine disabled IBPOC to low-wage, high-risk roles.

Healthcare access challenges during the pandemic further exemplify the structural racism and ableism embedded in public health systems. The lack of culturally competent care, coupled with inadequate telehealth infrastructure, exacerbated health disparities for disabled IBPOC, leaving many without critical medical and mental health support. This highlights the urgent need for healthcare systems to integrate culturally informed and disability-inclusive practices to ensure equitable access to care during public health crises and beyond (Lee et al., 2023; Yoshida et al., 2021).

The compounded caregiving burdens faced by families of disabled IBPOC reveal the systemic failures in addressing the intersection of race, disability, and socioeconomic status. The disruption of pediatric services and education programs placed an immense strain on caregivers, disproportionately affecting families already experiencing economic and social vulnerabilities. These findings underscore the necessity of robust social safety nets, equitable resource distribution, and community-based support systems to mitigate the long-term impacts of such disruptions (Running Bear et al., 2021).

Psychosocial stressors, including worsening mental health and increased IPV, reflect the heightened vulnerability of disabled IBPOC women and other intersectionally marginalized groups during the pandemic. The documented rise in IPV and sexual violence highlights systemic gaps in providing accessible, culturally sensitive support services for survivors. Beyond immediate interventions, these findings point to the need for broader structural reforms to address the intersecting oppressions of racism, ableism, and gender-based violence (NIDWAN, 2021; Minority Rights Group, 2020).

Finally, the resilience and agency demonstrated by disabled IBPOC through mutual aid, community organizing, and creative expression offer critical insights into resistance strategies within marginalized communities. These actions illustrate the importance of centring the voices and leadership of disabled IBPOC in the development of policies and programs aimed at addressing systemic inequities. Their experiences provide a blueprint for fostering community resilience and promoting equity in future public health emergencies (Torres, 2020; Asia Indigenous People’s Pact, 2020).

Above all, this review underscores how systemic racism, colonialism, and ableism intersected with the COVID-19 pandemic to disproportionately harm disabled IBPOC. The implications of these findings extend beyond the immediate impacts of the pandemic, emphasizing the enduring need for intersectional, equity-focused approaches in research, policy, and practice. Addressing these inequities requires sustained efforts to dismantle systemic barriers, foster inclusion, and ensure that recovery efforts are just and equitable.

Long-Term Implications and Unanswered Questions

Given the above, significant gaps remain regarding longer-term consequences of the pandemic. Public narratives declaring the pandemic "over" reflect privileged experiences, overlooking that many racialized and disabled communities continue to experience persistent disruptions as a new baseline of inequity (Reicher et al., 2025). Structural conditions shaped by racism, ableism, and socioeconomic precarity continue to determine who remains at risk of illness, who receives adequate post-COVID care, and who faces lasting economic and social hardships.

First, temporary supports, such as virtual or flexible services, remote work, and expanded relief programs, are now quietly being rolled back, despite continued relevance for many disabled individuals (Abrams, 2022). Initially celebrated as breakthroughs in accessibility, innovations (e.g., telehealth, flexible educational and occupational accommodations, and expanded relief access) revealed limitations for communities lacking high-speed internet, private spaces, or culturally-safe services. Further, many of these resources were never fully accessible due to language exclusion, poor digital infrastructure, and high service thresholds, potentially exacerbating inequities. It remains to be seen how these rollbacks are likely reproducing or deepening existing inequities among racialized disabled populations.

Second, and related to the above, changes to urban life, such as reduced public transit frequency, early business closures, increased cost of living, and cuts to community programming, have not returned to pre-pandemic norms (Nicola et al., 2020). These ongoing changes likely disproportionately isolate disabled and low-income IBPOC communities, intensifying social exclusion and economic hardship during the supposed recovery period; however, not much is documented on this topic thus far.

Third, although mass media coverage has diminished, health risks remain acute for immunocompromised individuals (Del Rio et al., 2020), those continuing to struggle with mental health and related struggles (e.g., burnout, homelessness, addiction) as a result of lockdowns (Panchal et al., 2023), and experiencing ongoing effects from COVID-19 infection (e.g., Long COVID), as well as COVID-19 vaccine delivery (e.g., side effects such as peri-/myo-carditis, reduced vaccine access, vaccine hesitancy) (Khan et al., 2021; Shearn & Krockow, 2023). Few studies have explored how these health complications intersect with systemic racism, ableism, and medical distrust.

Fourth, certain populations remain notably underrepresented in the literature. Despite growing public visibility (Abdelnour et al., 2022), ADHD and other neurodivergences outside of ASD were not explicitly addressed in any included studies. Similarly, refugee populations with disabilities, who face compounded barriers from restrictive policies, language exclusions, surveillance, and threats from immigration enforcement (e.g., ICE), received minimal attention. The evolving sociopolitical context, including anti-immigrant rhetoric, police expansion, and far-right political gains globally, rooted partly in heightened anti-Asian racism emerging from COVID-19, pose continued risks and remain underexplored in formal research despite their tangible influence on IBPOC communities with disabilities (Lee & Johnstone, 2020).

Finally, the literature consistently lacked meaningful consultation with IBPOC disabled communities in policy development and emergency responses. This exclusion undermines effective recovery strategies, equity in service delivery, and trust in public systems moving forward. Without sustained, community-driven involvement, the inequities exposed during the pandemic risk becoming further entrenched in the post-pandemic era.

In sum, lessons from the pandemic risk being overshadowed by dominant narratives of returning to "normal," even though "normal" was never equitable or safe for IBPOC, disabled, and intersectional populations. The impacts of racism, ableism, and colonialism, clearly exposed during the pandemic, will continue to shape health, education, and economic outcomes for years to come.

Recommendations for Practice

Findings from this review demonstrate the profound and multifaceted impacts of COVID-19 on disabled IBPOC and highlight the need for tailored, intersectional supports both during and beyond the pandemic. Addressing these inequities requires immediate and sustained efforts across public health, education, and social policy.

First, ensuring accessible and culturally informed communication is a critical first step. Multilingual, sign-language, and culturally appropriate materials must be prioritized to ensure IBPOC communities are not excluded from vital health information and services (Hassiotis, 2020; Minority Rights Group, 2020; Twardzik et al., 2021). Healthcare systems must improve coordination among governments, hospitals, and suppliers to ensure equitable allocation of resources such as PPE and medical supplies. Policymakers should collaborate with IBPOC community representatives, including Indigenous leaders, to co-develop inclusive policies and partner with local organizations to address intersecting challenges related to race, disability, and socioeconomic inequities (Lee et al., 2023; Paterson, 2020; Minority Rights Group, 2020). Concurrently, healthcare providers must receive training to recognize and mitigate implicit biases, fostering more equitable patient-provider relationships. Collecting disaggregated data on race, disability, gender, and socioeconomic status is equally essential for tailoring interventions and informing equitable policies (Hassiotis, 2020; Kana et al., 2020).

Next, education systems must implement evidence-based practices to enhance teacher competence in disability-inclusive education for both in-person and online settings. Resource disparities in low-income, rural, and reservation communities must also be addressed to ensure equitable access to technology and educational supports for disabled IBPOC children. Beyond education, programs supporting survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) must be accessible and culturally responsive, acknowledging the unique barriers faced by disabled IBPOC women and other marginalized groups (Hahmann, 2021; NIDWAN, 2021).

Further, recovery efforts should prioritize geographic accessibility, ensuring services such as COVID-19 recovery centres are located near IBPOC communities to minimize transportation barriers. Long-term strategies must focus on combating systemic racism, gender-based violence, and disability-based discrimination through advocacy, education, and structural reform. By centring the voices of disabled IBPOC in these efforts, we can build more inclusive, equitable systems capable of addressing the complex needs of this population in future public health crises and beyond (Paterson, 2020; Sholas, 2020).

Study Limitations and Recommendations for Research

While this review highlights significant inequities and areas for intervention, several gaps in the literature remain. While the review applied an inclusive definition of disability and included a wide range of impairments, many studies used general terminology without specifying disability type; the majority that did identify specific disabilities predominantly focused on IDDs and/or ASD. This limited our ability to consistently disaggregate findings across various types of disability and examine outcomes for different disability sub-populations. Furthermore, although our search strategy included terms such as “neurodiversity,” we note that some populations, such as individuals with ADHD, were not explicitly represented at all in any of the included sources. Additionally, research on disabled IBPOC frequently neglected intersectional identities, including nonbinary, trans, or Two-Spirit individuals, whose experiences of racism, ableism, and gender-based violence likely differ markedly from those of cisgender men and women.

A notable limitation is the geographic concentration of peer-reviewed studies, with the majority conducted in the United States. This predominance restricts the generalizability of findings and demonstrates how research often fails to capture the diverse experiences of disabled IBPOC in other regions of Europe and Asia, such as Eastern Europe and the Middle East, as well as regions like South America and Africa. Although grey literature provided a more global perspective, it remained unevenly distributed across different regions, still limiting comprehensive international insights.

Furthermore, disaggregated data on COVID-19-related health outcomes by race and disability were largely absent in most studies. This lack of detailed data not only hampers a nuanced understanding of the pandemic’s impacts on disabled IBPOC but also mirrors broader systemic failures in addressing racism and ableism within research and policy frameworks. Many studies utilized qualitative methods with small, non-representative samples, which may constrain the applicability of their findings. Additionally, there is a scarcity of longitudinal research that examines the long-term impacts of the pandemic on disabled IBPOC populations.

Relatedly, while the grey literature search was guided by explicit inclusion criteria, the unstructured and voluminous nature of results made comprehensive coverage impractical. In line with the scoping aims of this review, this study prioritized conceptual depth over statistical representativeness. The final sample is therefore illustrative, reflecting thematic saturation rather than exhaustive documentation of all possible impacts.

Lastly, variability in the definitions and measurements of race, ethnicity, and disability across studies also posed challenges for comparing and synthesizing findings effectively. Addressing these gaps necessitates greater representation of IBPOC voices in research design and data collection processes, as well as the standardization of definitions and measurements for key variables.

Future research should adopt intersectional approaches that consider the interplay of multiple identities, such as race, gender, disability type, and socioeconomic status. Expanding studies to include diverse geographic contexts will enhance the global understanding of disabled IBPOC experiences. Longitudinal and mixed-methods studies are essential to provide deeper insights into the enduring and multifaceted impacts of the pandemic. Additionally, exploring resilience and coping mechanisms within disabled IBPOC communities can offer a more comprehensive perspective on how these groups navigate and overcome systemic challenges during public health crises. Emphasizing collaboration with IBPOC communities will ensure that research is culturally appropriate and addresses the unique needs of these marginalized subpopulations.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on minority-status IBPOC individuals, families, children, and women with disabilities, who faced heightened stress, mental health challenges, and increased exposure to violence and discrimination, exacerbated by socioeconomic factors such as poverty and limited access to resources. These intersectional vulnerabilities underscore the urgent need for research that adopts intersectional approaches to better understand and address these disparities. In practice, public health policies must prioritize equitable resource allocation and ensure culturally appropriate services tailored to the unique needs of marginalized groups. Additionally, society must actively work to dismantle systemic racism and ableism, fostering inclusive support systems. By addressing these critical areas, we can create more resilient and equitable outcomes for marginalized communities in future crises.

Endnotes

References

- Abrams, A. (2022, April 15). Disabled Americans push to keep accessible pandemic policies. Time Magazine. https://time.com/6166957/disabled-americans-covid-19-policies/

- Abimbola, S. (2023). The foreign gaze: authorship in academic global health. BMJ Global Health, 8(12), e013111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013111

- Abdelnour, E., Jansen, M. O., & Gold, J. A. (2022). ADHD Diagnostic Trends: Increased Recognition or Overdiagnosis?. Missouri medicine, 119(5), 467–473.

- *Alba, L. A., Mercado Anazagasty, J., Ramirez, A., & Johnson, A. H. (2022). Parents' perspectives about special education needs during COVID-19: Differences between Spanish and English-speaking parents. Journal of Latinos and Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2022.2056184

- *Aquino, K. C., & Scott, S. (2022). Disability resource professionals’ perceived challenges in minority-serving institutions during COVID-19: Recommendations for supporting students with disabilities. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 15(5), 542-547. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000428

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- *Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact. (2020, November). Break through the Crisis: Struggle and Strive of Indigenous Women and Indigenous Persons with Disability. COVID-19: A Special Volume on Indigenous Women and Indigenous Persons with Disabilities. https://aippnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Flashupdate-4-FINAL.pdf

- Barbu, M. G., Thompson, R. J., Thompson, D. C., Cretoiu, D., & Suciu, N. (2020). The Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the Most Common Comorbidities–A Retrospective Study on 814 COVID-19 Deaths in Romania. Frontiers in Medicine, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.567199

- Beaudry, J. S., & Miller, L. E. (2016). Research design in the social sciences: Interdisciplinary approaches. SAGE Publications.

- *Bergmans, R. S., Chambers-Peeple, K., Aboul-Hassan, D., Dell’Imperio, S., Martin, A., Wegryn-Jones, R., Xiao, L. Z., Yu, C., Williams, D. A., Clauw, D. J., & DeJonckheere, M. (2022). Opportunities to improve long COVID care: Implications from semi-structured interviews with Black patients. The Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, 15(6), 715-728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-022-00594-8

- *Brooks, J. D., & Von Schrader, S. (2023). An accommodation for whom? Has the COVID-19 pandemic changed the landscape of flexible and remote work for workers with disabilities? Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-023-09472-3

- Cameron, B. L., Carmargo Plazas, M. del P., Salas, A. S., Bourque Bearskin, R. L., & Hungler, K. (2014). Understanding Inequalities in Access to Health Care Services for Aboriginal People. Advances in Nursing Science, 37(3), E1–E16. https://doi.org/10.1097/ans.0000000000000039

- *Chakraborty, J. (2020). Social inequities in the distribution of COVID-19: An intra-categorical analysis of people with disabilities in the U.S. Disability and Health Journal, 14(1), 101007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101007

- Charron-Chénier, R., & Mueller, C. W. (2018). Racial Disparities in Medical Spending: Healthcare Expenditures for Black and White Households (2013–2015). Race and Social Problems, 10(2), 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-018-9226-4

- *Cioè-Peña, M. (2022). Computers Secured, Connection Still Needed: Understanding How COVID-19-related Remote Schooling Impacted Spanish-speaking Mothers of Emergent Bilinguals with Dis/abilities. Journal of Latinos and Education, 21(3), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2022.2051036

- Crouse Quinn, S., Jamison, A. M., Freimuth, V. S., An, J., & Hancock, G. R. (2017). Determinants of influenza vaccination among high-risk black and white adults. Vaccine, 35(51), 7154-7159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.083

- *Dababnah, S., Kim, I., Wang, Y., & Reyes, C. (2021). Brief report: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Asian American families with children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 34(3), 491-504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-021-09810-z

- DeJong, C., Katz, M. H., & Covinsky, K. (2020). Deferral of Care for Serious Non–COVID-19 Conditions. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(2). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4016

- Del Rio, C., Collins, L. F., & Malani, P. (2020). Long-term health consequences of COVID-19. JAMA, 324(17), 1723. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.19719

- *Dodds, R. L., & Maurer, K. J. (2022). Pandemic stress and coping in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities in urban Los Angeles: A qualitative interview study. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(3), 165-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2022.2076960

- Evans, M. L., Lindauer, M., & Farrell, M. E. (2020). A Pandemic within a Pandemic — Intimate Partner Violence during Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(24), 2302–2304. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2024046

- Fusch, P., & Ness, L. (2015). Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. The Qualitative Report, 20(9). https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2281

- *Geuijen, P. M., Vromans, L., & Embregts, P. J. (2021). A qualitative investigation of support workers’ experiences of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Dutch migrant families who have children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 46(4), 300-305. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2021.1947210

- *Gonzales, C. W., Simonell, J. R., Lai, M. H., Lopez, S. R., & Tarbox, J. (2023). The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on therapy utilization among racially/Ethnically and socio-economically diverse autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-023-05905-y

- Greenwood, N. W., Dreyfus, D., & Wilkinson, J. (2014). More Than Just a Mammogram: Breast Cancer Screening Perspectives of Relatives of Women with Intellectual Disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 52(6), 444–455. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-52.6.444

- *Gurung, P. (2020, July 20). Include Indigenous People in COVID-19 response. International Labour Organization. https://labordoc.ilo.org/discovery/delivery/41ILO_INST:41ILO_V1/1271879840002676

- *Gurung, P. (2021). COVID 19 in Nepal: The impact on Indigenous peoples and persons with disabilities. Disability and the Global South, 8(1), 1910-1922. https://dgsjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/dgs08_01_03.pdf

Special Issue: COVID-19 in South Asia (Jawaharlal Nehru University, India; Western Sydney University, Australia) - *Hahmann, T. (2021, February 1). Changes to health, access to health services, and the ability to meet financial obligations among Indigenous People with long-term conditions or disabilities since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (1). Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00006-eng.htm

- Hassiotis, A. (2020). The Intersectionality of Ethnicity/race and Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Impact on Health Profiles, Service Access and Mortality. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 13(3), 171–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2020.1790702

- Henning-Smith, C. E., Hernandez, A. M., Hardeman, R. R., Ramirez, M. R., & Kozhimannil, K. B. (2019). Rural Counties with Majority Black or Indigenous Populations Suffer the Highest Rates of Premature Death in the US. Health Affairs, 38(12), 2019–2026. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00847

- *Holm, M. E., Skogberg, N., Kiviruusu, O., & Sainio, P. (2024). Immigrant origin and disability increase risk for anxiety among youth during COVID-19: The role of unmet needs for support in distance learning and family conflicts. Journal of Adolescent Health, 74(5), 916-924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.12.006

- *Holmes, R., Kearney, L., Gopal, S., & Daddi, I. (2023). ‘Lots of Black people are on meds because they're seen as aggressive’: STOMP, COVID‐19 and anti‐racism in community learning disability services. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 52(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12541

- *Hong, J. Y., Choi, S., Francis, G. L., & Park, H. (2021). Stress among korean immigrant parents of children with diagnosed needs amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The School Community Journal, 31(2), 31-51.

- Hughes, J., & Sharp, C. (2021). Identifying key databases for systematic and scoping reviews in social sciences: Insights and recommendations. Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 45(3), 112-125.

- Hwang, J., & Smith, L. (2023). Barriers to healthcare access among persons with disabilities: A global perspective. International Journal for Equity in Health, 22(1), Article 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-023-02035-w

- *Jones, B., King, P. T., Baker, G., & Ingham, T. (2020). COVID-19, intersectionality, and health equity for Indigenous Peoples with lived experience of disability. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 44(2), 71-88. https://doi.org/10.17953/aicrj.44.2.jones

- Kana, L. A., Shuman, A. G., Helman, J., Krawcke, K., & Brown, D. J. (2020). Disparities and ethical considerations for children with tracheostomies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 13(3), 371–376. https://doi.org/10.3233/prm-200749

- Khan, M. S., Ali, S. A., Adelaine, A., & Karan, A. (2021). Rethinking vaccine hesitancy among minority groups. The Lancet, 397(10288), 1863-1865. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00938-7

- Kitching, G. T., Firestone, M., Schei, B., Wolfe, S., Bourgeois, C., O’Campo, P., Rotondi, M., Nisenbaum, R., Maddox, R., & Smylie, J. (2019). Unmet health needs and discrimination by healthcare providers among an Indigenous population in Toronto, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111(1). https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-019-00242-z

- Kurre, P. A. (2014). Orthopaedic Care Coordination for the Intellectually and Developmentally Disabled Adult in the Residential Care Setting. Orthopaedic Nursing, 33(5), 251–254. https://doi.org/10.1097/nor.0000000000000080

- Lee, E., & Johnstone, M. (2020). Resisting the politics of the pandemic and racism to foster humanity. Qualitative Social Work, 20(1-2), 225-232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325020973313

- *Lee, D., Kett, P. M., Mohammed, S. A., Frogner, B. K., & Sabin, J. (2023). Inequitable care delivery toward COVID-19 positive people of color and people with disabilities. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(4), e0001499-e0001499. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001499

- *Lee, S. H., & Jung, A. W. (2023). Korean American children with disabilities and their at-home distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from a survey of parents. The Journal of International Special Needs Education, 26(1), 36-47. https://doi.org/10.9782/JISNE-D-22-00005

- *Luna, A., Zulauf-McCurdy, C. A., Harbin, S., & Fettig, A. (2023). Latina mothers of young children with special needs: Personal narratives capturing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 42(4), 302-314. https://doi.org/10.1177/02711214221129240

- Magaña, S., Parish, S., Morales, M. A., Li, H., & Fujiura, G. (2016). Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities Among People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 54(3), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-54.3.161

- *Martinez, B., & Correa-Torres, S. (2023). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish speaking families who have children with disabilities. Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 10(1). https://digscholarship.unco.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1119&context=jeri

- *Mayorga, N. A., Manning, K. F., Garey, L., Viana, A. G., Ditre, J. W., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2022). The role of experiential avoidance in terms of fatigue and pain during COVID-19 among Latinx adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46(3), 470-479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-022-10292-2

- *Millett, G. A., Jones, A. T., Benkeser, D., Baral, S., Mercer, L., Beyrer, C., Honermann, B., Lankiewicz, E., Mena, L., Crowley, J. S., Sherwood, J., & Sullivan, P. S. (2020). Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on Black communities. Annals of Epidemiology, 47, 37-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.003

- *Minority Rights Group. (2020, April 27). Statement on the Impact of the Global COVID-19 Pandemic on Persons with Disabilities from Minority, Indigenous and other Marginalised Communities – Riadis | Red Latinoamericana de Organizaciones. RIADIS. http://www.riadis.org/statement-on-the-impact-of-the-global-covid-19-pandemic-on-persons-with-disabilities-from-minority-indigenous-and-other-marginalised-communities/

- Mirza, M., Luna, R., Mathews, B., Hasnain, R., Hebert, E., Niebauer, A., & Mishra, U. D. (2013). Barriers to Healthcare Access Among Refugees with Disabilities and Chronic Health Conditions Resettled in the US Midwest. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16(4), 733–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9906-5

- *Moore, C. L., Manyibe, E. O., Ward-Sutton, C., Webb, K., Wang, P., Washington, A. L., & Peterson, G. (2022). National benchmark study of employment equity among multiply marginalized persons of color with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic: A bootstrap approach. The Journal of Rehabilitation, 88(1), 108-118.

- Nader, F., Kolahdooz, F., & Sharma, S. (2017). Assessing Health Care Access and Use among Indigenous Peoples in Alberta: A Systematic Review. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 28(4), 1286–1303. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2017.0114

- *National Disability Institute. (2020, September 2). Race, ethnicity and disability: The financial impact of systemic inequality. https://www.nationaldisabilityinstitute.org/reports/research-brief-race-ethnicity-and-disability/

- *National Indigenous Disabled Women Association Nepal (NIDWAN). (2021, January 23). National Consultation and Learning Workshop on COVID-19: Issues of Indigenous Youth and Women with Disabilities. International Disability Alliance; National Indigenous Disabled Women Association Nepal (NIDWAN). https://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/covid-Indigenous-youth-women-with-disabilities

- *Neece, C., McIntyre, L. L., & Fenning, R. (2020). Examining the impact of COVID‐19 in ethnically diverse families with young children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 64(10), 739-749. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12769

- Nicola, M., Alsafi, Z., Sohrabi, C., Kerwan, A., Al-Jabir, A., Iosifidis, C., Agha, M., & Agha, R. (2020). The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International journal of surgery (London, England), 78, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018

- *Nolan, S. L. (2021). The compounded burden of being a Black and disabled student during the age of COVID-19. Disability & Society, 37(1), 148-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1916889

- *Nvé Díaz San Francisco, C., Zhen-Duan, J., Fukuda, M., & Alegría, M. (2023). Attitudes and perceptions toward the COVID-19 risk-mitigation strategies among racially and ethnically diverse older adults in the United States and Puerto Rico: A qualitative study. Ethnicity & Health, 29(1), 25-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2023.2243548

- *Okonkwo, Ada Jane. (2020, December 8). Navigating COVID-19 for Indigenous Persons with Disabilities and Their Families. Plan Institute. https://planinstitute.ca/2020/12/08/navigating-covid-19-for-indigenous-persons-with-disabilities-and-their-families/

- Pace, J. E., Shin, M., & Rasmussen, S. A. (2011). Understanding physicians’ attitudes toward people with Down syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 155(6), 1258–1263. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.34039

- Panchal, N., Saunders, H., Rudowitz, R., & Cox, C. (2023, April 25). The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. KFF. https://www.kff.org/mental-health/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/

- *Paterson, J. (2020). Left Out: Children and youth with special needs in the pandemic. Representative for Children and Youth. https://rcybc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CYSN_Report.pdf

- *Pitts, P. (2020, July 16). Including Indigenous People with Disabilities in COVID-19 Responses. Cultural Survival. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/including-indigenous-people-disabilities-covid-19-responses

- *Reber, L., Kreschmer, J. M., DeShong, G. L., & Meade, M. A. (2022). Fear, isolation, and invisibility during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study of adults with physical disabilities in marginalized communities in southeastern Michigan in the United States. Disabilities, 2(1), 119-130. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2010010

- Reicher, S., Clarke, R., Behr, R., & Ryan, F. (2025, March 1). Five years on from the pandemic, how has Covid changed our world? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/mar/01/five-years-covid-first-lockdown-lives-changed

- *Rios, K., & Aleman‐Tovar, J. (2022). Documenting the advocacy experiences among eight Latina mothers of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 20(1), 89-103. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12444

- *Running Bear, C., Terrill, W. P., Frates, A., Peterson, P., & Ulrich, J. (2021). Challenges for rural Native American students with disabilities during COVID-19. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 40(2), 60-69. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756870520982294

- Saadi, A., Himmelstein, D. U., Woolhandler, S., & Mejia, N. I. (2017). Racial disparities in neurologic health care access and utilization in the United States. Neurology, 88(24), 2268–2275. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000004025

- *Schall, C., Brooke, V., Rounds, R., & Lynch, A. (2021). The resiliency of employees with intellectual and developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic and economic shutdown: A retrospective review of employment files. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 54(1), 15-24. https://doi.org/10.3233/jvr-201113

- *Schur, L., Van der Meulen Rodgers, Y., & Kruse, D. (2021). COVID-19 and employment losses for workers with disabilities: An intersectional approach. Center for Women and Work, Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations. https://smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/Documents/Centers/CWW/Publications/draft_covid19_and_disability_report.pdf

- Shearn, C., & Krockow, E. M. (2023). Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in ethnic minority groups: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of initial attitudes in qualitative research. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health, 3, 100210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100210

- *Shenk, M., Hicks, B., Quiñones, A., & Harrati, A. (2023). Racial disparities in COVID-19 experiences among older adults with disabling conditions. Journal of Aging and Health, 36(5-6), 320-336. https://doi.org/10.1177/08982643231185689

- Sholas, M. G. (2020). The actual and potential impact of the novel 2019 coronavirus on pediatric rehabilitation: A commentary and review of its effects and potential disparate influence on Black, Latinx and Native American marginalized populations in the United States. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 13(3), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3233/prm-200722

- Song, M. (2020). Rethinking minority status and “visibility.” Comparative Migration Studies, 8(1).https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0162-2

- *Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Mirza, M., Errisuriz, V. L., Zeng, W., Brown, J. P., Vanegas, S., Heydarian, N., Parra-Medina, D., Morales, P., Torres, H., & Magaña, S. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and well-being of Latinx caregivers of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7971. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157971

- The University of British Columbia. (2023, July 5). Equity and inclusion glossary of terms. UBC Equity & Inclusion Office. https://equity.ubc.ca/resources/equity-inclusion-glossary-of-terms/

- *Torres, L. E. (2020). Straddling death and (Re)birth: A disabled Latina’s meditation on collective care and mending in pandemic times. Qualitative Inquiry, 27(7), 895-904. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420960169

- *Trainor, A., Romano, L., Sarkissian, G., & Newman, L. (2023). The COVID-19 pandemic as a tipping point: The precarity of transition for students who receive special education and English language services. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 58(3), 339-347. https://doi.org/10.3233/jvr-230011

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., ... & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467-473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Turpel-Lafond, M. E. (2020). In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care. In Addressing Racism Review: Full Report. https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2020/11/In-Plain-Sight-Summary-Report.pdf

- Twardzik, E., Williams, M., & Meshesha, H. (2021). Disability During a Pandemic: Student Reflections on Risk, Inequity, and Opportunity. American Journal of Public Health, 111(1), 85–87. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2020.306026

- *Uldry, M., & Leenknecht, A. (2021). European human rights report: Impact of COVID-19 on persons with disabilities (5). European Disability Forum. https://mcusercontent.com/865a5bbea1086c57a41cc876d/files/08348aa3-85bc-46e5-aab4-cf8b976ad213/EDF_HR_report_2021_interactive_accessible.pdf

- *Umpleby, K., Roberts, C., Cooper-Moss, N., Chesterton, L., Ditzel, N., Garner, C., Clark, S., Butt, J., Hatton, C., Chauhan, U. (2023). We deserve better: Ethnic minorities with a learning disability and barriers to healthcare. Race and Health Observatory Report. https://www.nhsrho.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Part-A-RHO-LD-Policy-Data-Review-Report.pdf

- United Nations. (n.d.). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities - Articles | United Nations Enable. United Nations Organization. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html

- *Voluntary Organizations Disability Group (VODG). (2022). A spotlight on injustice: The final report from the Commission on COVID-19, ableism and racism. https://www.vodg.org.uk/resource/a-spotlight-on-injustice-the-final-report-from-the-commission-on-covid-19-ableism-and-racism.html

- Williamson, H. J., Contreras, G. M., Rodriguez, E. S., Smith, J. M., & Perkins, E. A. (2017). Health Care Access for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Scoping Review. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 37(4), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449217714148

- World Health Organization. (2020a, January 21). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation report – 1. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2020b, March 11). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020