Embodiment and the Disabled (Extraordinary) Body: Carol Chase Bjerke’s Hidden Agenda and the External Internality of Ostomie

L’incarnation et le corps handicapé (extraordinaire) : Hidden Agenda de Carol Chase Bjerke et l’intériorité externe de l’ostomie

Heather Twele, PhD Candidate

Centre for the Study of Theory and Criticism

Western University

htwele [at] uwo [dot] ca

Abstract

This essay uses critical phenomenology to examine Carol Chase Bjerke’s ostomy art in Hidden Agenda. With an ostomy, the intestine erupts past the skin barrier and interrupts everyday life. Bjerke’s ostomy-centred installation pieces question the boundaries between subject and object, inside and outside, ability and disability, "I can" and "I cannot," clean and unclean. Bjerke molds "misfortune cookies," stoma wallpaper and rose-colored glasses (reading glasses with stoma-shaped lenses) to reframe lived ostomy experience, forcing the viewer to visualize a physical manifestation of the inherent in-betweenness of disability and externalize the hiddenness of the ostomy. Drawing on the personal phenomenological perspectives of Bjerke’s artistic practice, part of her "Art and Healing" trilogy that documents her own response to living with an ostomy after treatment for colorectal cancer, and my own lived experience, I argue that the ostomy as a liminal state of disability not only resists ableist binaries; it also marks a productive site through which to view disability itself as the lived experience of a critical phenomenology. The simultaneity of inside and outside defies precise definition, complicating and overturning the distinction between "fitting" and "misfitting." Playfully reshaping this liminality, this essay also meditates on the phenomenological strangeness of touching my own ostomy for the first time, drawing on the curious shifting between self and other to imagine a more complex intertwined embodiment.

Résumé

Cet essai mobilise la phénoménologie critique pour explorer l’art ostomique de Carol Chase Bjerke dans Hidden Agenda. L’ostomie, en faisant jaillir l’intestin au-delà de la barrière cutanée, bouleverse le quotidien. Les installations de Bjerke, centrées sur cette réalité corporelle, interrogent les frontières entre sujet et objet, intérieur et extérieur, capacité et incapacité, « je peux » et « je ne peux pas », propre et impur. Elle crée des « biscuits de malchance », du papier peint à motif de stomie et des lunettes teintées de rose, dont les verres sont en forme de stomie, afin de reconfigurer l’expérience vécue de l’ostomie. Ces œuvres contraignent les personnes spectatrices à visualiser une matérialisation physique de l’entredeux inhérent au handicap et à extérioriser ce qui est habituellement dissimulé. En m’appuyant sur les perspectives phénoménologiques personnelles issues de la pratique artistique de Bjerke, qui s’inscrit dans sa trilogie Art and Healing documentant sa propre réponse à la vie avec une ostomie après un traitement contre le cancer colorectal, ainsi que sur mon expérience vécue, je soutiens que l’ostomie, en tant qu’état liminaire du handicap, ne se contente pas de résister aux binarités capacitistes. Elle constitue également un espace fécond pour envisager le handicap comme expérience incarnée d’une phénoménologie critique. La simultanéité de l’intérieur et de l’extérieur échappe à toute définition stable, complexifiant et renversant la distinction entre adéquation et inadéquation. Ce texte propose aussi une méditation sur l’étrangeté phénoménologique du premier contact avec ma propre ostomie. En explorant le glissement curieux entre soi et autre, il devient possible d’imaginer une forme d’incarnation plus complexe, plus entrelacée.

Keywords: Critical phenomenology, critical disability studies, ostomy art, embodiment, identity, ability, disability, lived experience

Mots-clés : Phénoménologie critique, études critiques sur le handicap, art ostomique, incarnation, identité, capacité, handicap, expérience vécue

Introduction

Disability is a unique form of “perpetual embodiment” that is constantly shifting (Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception 169). This shifting disabled embodiment constitutes a presence rather than absence, contrary to negative ableist conflations. Embodiment, in general, is a perpetual reworking and reshaping of our flexible body schemas, through which we encounter and engage with the world and other people. To understand the uniqueness of disability embodiment more fully, I discuss Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s theory of embodiment as inhabiting the world in Phenomenology of Perception. I then draw on Merleau-Ponty’s theory of embodiment and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson’s concept of “misfitting” to analyze an artistic intervention into the “lived experience” of the disabled (extraordinary) body. Subjective, but not relative (Fielding, Cultivating 11), the narratorial role of disability experience through art, writing, and conversation is integral to a critical phenomenological inquiry into disabled ways of being (Reynolds 243-44). Disability narratives foreground the lived (phenomenal) disabled body, its locatedness, and its “fit” or “misfit” with societal, political, and economic background systems that structure our engagement with the world and other people.

In an often-jarring jolt(s), disability, acquired or not, disrupts the flexible fluctuating flow of embodiment, and the chiasmic “bodymind” (Price qtd. in Reynolds 244), which usually remains unnoticed in the background, takes centre stage as a dissonant presence (Nielson 2). The shifting disabled body schema is forced to adjust to social, economic, political, and physical barriers, and it can no longer operate smoothly in the background. Reciprocally, the foregrounding of the intersectional disabled phenomenal body also foregrounds systemic ableism among other deeply seated background ideologies. The chiasmic intertwining of body and world becomes a site of tension. I will use critical phenomenology as my method of analysis to flesh out the intricacies of disability experience in a highly ableist society through Carol Chase Bjerke’s ostomy installation Hidden Agenda. I will also explore how disabled and/or chronically ill people become the embodiment of a lived critical phenomenology through the necessity of hyper-awareness and self-reflexivity to navigate bodily and societal challenges. Art opens a necessary dialogue about the intricacies of this disabled embodiment, requiring viewers to imagine disability experience as a unique form of creative expression outside of restrictive ableist binaries.

Art as Experiential Dialogue: Critical Disability Studies and Critical Phenomenology

Art as embodied phenomenological exploration profoundly mediates between the accessible and inaccessible, accentuating the necessary incompleteness of everyday experience. Acknowledging the plurality of existence, art also reveals how we intersubjectively share the experiences of others (however partial). In this sense, art opens a window into the hyper self-reflexivity of disabled people, which is arguably heightened in the case of the ostomy, owing to the protrusion of a delicate internal organ beyond the skin barrier. This forced hyper self-reflexive state throws background systems and environments of ableist culture into relief, often resulting in a series of “misfits” that may or may not become “fits” (Garland-Thomson, “Misfits” 593). Critical phenomenology attempts to reveal and interrogate these background structures that often remain unexamined, especially by white, heterosexual, able-bodied people.

In this paper, I argue that disability is the lived experience of a critical phenomenology, and that art is a medium through which this fluid self-reflexivity is revealed in all its (in)accessible complexities. Critical phenomenology, as practiced by Helen Fielding, Mariana Ortega, and Joel Michael Reynolds, takes up Merleau-Ponty’s theory of habitual embodiment through perceptual experience and inhabitation and “mobilizes phenomenological description in the service of a reflexive inquiry into how power relations structure experience as well as our ability to analyze that experience” (Weiss, Murphy, & Salamon xiv). Focusing on situatedness, critical phenomenology acknowledges that every phenomenological description and inquiry begins from the “limitations and liabilities of its own perspective” (xiv). Within Critical Disability Studies (CDS), phenomenological academic accounts continue to privilege white Western disabled academics from the global North and to ignore voices/issues from the global South (Meekosha 2011, 668; Grech 2015), perpetuating “scholarly colonialism” (Meekosha 2011, 668). Many phenomenological accounts of white Western disability are steeped in privilege. Critical phenomenology remains an important methodology through which to explore disabled embodiment, but disabled academics must remain attune to the rest of the systemic web of oppression in which ableism is entangled.

In her art installation exhibit Hidden Agenda: ARTiculating the Unspeakable, the “limitations and liabilities” of Carol Chase Bjerke’s subjective perspective in her exploration of ostomies is what makes her artistic practice distinctly phenomenological. Her artistic commentary stems from her own experiences of medical intervention in the United States. Bjerke draws from her experiences with an ostomy, an opening in the abdominal wall that expels waste into an external bag. The fact that Bjerke’s art comments on underlying social stigma of ostomies and the taken-for-granted nature of surgical ostomy procedures centers her art within critical phenomenology, in particular. In turn, Bjerke comments on the “barbaric practice” of ostomy surgeries without acknowledging the thousands of people who are denied access to this life-saving procedure. She focuses on the thousands of ostomies created each year, not the thousands of people around the world who do not have access to surgical intervention or ostomy supplies. My own phenomenological account of having an ileostomy is steeped in white Western heterosexual privilege of access to affordable medical intervention and ostomy supplies in Canada. In this article, I focus specifically on Bjerke’s ostomy art, thus centering this phenomenological exploration once again in a white Western framework. In this way, I admit that I participate in the perpetuation of “scholarly colonialism,” and in future phenomenological explorations, I want to try to interrupt this Western academic cycle, which is particularly still predominant in CDS. Although I believe that Bjerke’s and my own experiences reveal important intertwining nuances of disability and chronic illness, other non-Western first-person phenomenological explorations need to interrupt our ethnically privileged accounts of medical access and choice.

Critical phenomenology is a particularly effective method of inquiry for uncovering experiences of disability and/or chronic illness. This reflexive mode of inquiry poignantly reveals the pervasive ableist power structures (among many other power structures) that inform our experiences and point the way to disabled embodiment that rejects restrictive ableist binaries. Several notable academics who employ a critical phenomenological method within Critical Disability Studies include Simon Dickel (2022), Joel Michael Reynolds (2022), Jonathan Sterne (2021), and Corinne Lajoie (2019, 2022). In Embodying Difference: Critical Phenomenology and Narratives of Disability, Race, and Sexuality (2022), Simon Dickel employs a phenomenological lens to explore the intertwining spaces of disability studies, critical race theory, and queer studies, engaging with lived embodied accounts of disability experience. Through a Merleau-Pontian phenomenological framework, Joel Michael Reynolds (2022) also traverses discussions of gender, race, and disability, notably emphasizing the need to break the ableist conflation of disability with pain in The Life Worth Living: Disability, Pain, and Morality. In Diminished Faculties: A Political Phenomenology of Impairment, Jonathan Sterne (2021) explores the “unreliable narrator” who is an integral part of impairment phenomenology. Recounting personal experiences of surgery for thyroid cancer and a paralyzed vocal cord, Sterne describes his own unreliability as a narrator as “my inaccessible-to-myself-self” (40). Focusing on mental illness and phenomenology of spaces, Corinne Lajoie explores how “experiences of disorientation” (2019, 546) highlight the necessary intersubjectivity of human embodiment and how current concepts of access and belonging need to be ‘cripped’ to open spaces up to even more different ways of being (2022, 318). Each of these authors use phenomenology to explore different ways of being that fall outside of ableist normative standards, and although Carol Chase Bjerke does not specifically use the term phenomenology, her ostomy art is distinctly phenomenological.

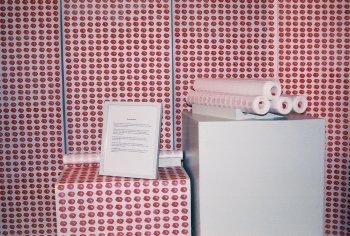

Art, such as Bjerke’s ostomy art, can reveal the (un)intentional practice of critical phenomenology through the disabled body, intertwining form and content in a raw disorienting and defamiliarizing way. Confronting the viewer, art forces recognition and reflectiveness, which often turns into self-reflexivity. Between 2003-2011, visual artist Carol Chase Bjerke created a series of installation pieces centering around ostomies called Hidden Agenda: ARTiculating the Unspeakable.[1] The exhibit Hidden Agenda is part of Bjerke’s “Art and Healing” trilogy, which documents Bjerke’s experience of living with an ostomy after treatment for colorectal cancer. Her ostomy artwork explores her “altered body” after surgery and her re-embodiment journey (xii). Bjerke’s installation of Hidden Agenda in 2009 is both personal and impersonal, hovering between intensely subjective experiences and the clinical sterilized exhibition walls, tables, and medical packaging (Figures 1 & 2). The walls of the installation are papered with long strips of red dotted paper, which upon closer examination are thousands of hand-stamped red ostomies. Beneath a box of plexiglass on a display stand, red clay ostomy-shaped “Misfortune Cookies” line three levels (Figure 1). In the left hand corner, ostomy paper scrolls, like the sheets lining the walls, lie on top of two raised bases, with one scroll partially unrolled (Figures 3-5). On the righthand side, ostomy sizing guides forming an accordion booklet titled “How Long Can I Make It?” stand partially unfolded, protected underneath another plexiglass box (Figure 6). The piece “Privacy Screens” with clear ostomy packaging hanging from red strings stands beside the accordion booklet display and a raised base with informational pamphlets.

Expressing closeness (intimate personal experiences) and distance (plexiglass covers) simultaneously, Bjerke’s installation is a profound physical representation of the benefits and limitations of phenomenological inquiry: other people’s narratives are windows into their personal embodied experiences, but a glass (or plexiglass) window will always be inserted in between not allowing full access, mediating our external understanding of those personal subjective experiences. However, these limitations of phenomenological investigation do not signal phenomenology as useless (or less than other modes of knowledge). The inherent heightened unstable subjectivity of phenomenology, as illustrated in Bjerke’s installation, is a particularly potent method of inquiry into disabled embodiment because it acknowledges and embraces the constantly shifting essence of re-embodiment as our bodies inhabit the world. Disability is hard to pin down, and critical phenomenology’s methodology shifts with these slipping sites of tension, rather than trying to force disability into a preformed normative category.

The “misfitting” body could be considered a critical phenomenological body that performs self-reflexive inquiry into habitual lived experience daily and hourly. Coined by Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, the unstable and flexible terms “fitting” and “misfitting” help to “defamiliarize” and “reframe” (mis)understandings of the disabled body as well as to dispel the “fantasy” of the “stable, predictable, or controllable” body (“Misfits” 592, 603). Rather than locating the source of the “misfit” within the disabled body, as in the medical model, the issue of the “misfit” occurs within the interaction between disabled body and the world, or the disabled body and the able-bodied (593). Thus, to “misfit” is a contextual and relational “juxtaposition” or “discrepancy between body and world” (593). However, “the fragility of fitting,” the possibility of fitting one moment and misfitting the next, extends to the entirety of lived experience, including able-bodied and disabled bodies alike (597). Artist and design researcher Sara Hendren describes Garland-Thompson’s term “misfitting” as “a deceptively casual word” that has become “a bracing shorthand” for disharmonious relationships between body and the built environment (16). For Hendren, the “square-peg, round-hold conundrum” of “misfitting” (21), following Garland-Thomson’s potent metaphor, encompasses the “obvious collisions” as well as “the quieter ones” (16). Taking up “misfitting” from an “adaptive technology” standpoint (25), Hendren discusses making, “unmaking,” and “remaking” the “unfinished” world through useful and creative tools that amplify and extend the body’s grasp on the world, extensions which both disabled and nondisabled people use daily (27-30). The “body-plus” (27) is Hendren’s term for the tools that we use in everyday experience to adapt to the “[c]losures and openings,” barriers and generative opportunities, within lived experience (28). In concert with Garland-Thomson and Hendren, I will focus my discussion of “misfitting” in relation to disabled bodies, specifically the spatial and social “misfitting” that can occur with having an ostomy and the heightened “body-plus” experience of the plastic ostomy appliance glued to one’s abdomen.

Grappling with the fleshly “messiness of bodily variety” (Garland-Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies 8), I illustrate the uniqueness of disability embodiment and identity through Bjerke’s phenomenological exploration of ostomies in her installation exhibit Hidden Agenda and through my own personal experience with an ileostomy. Intertwining Merleau-Ponty, Garland-Thomson, and Hendren’s theories, I investigate how ostomies, as the intestine erupts past the skin barrier, question the boundaries between subject and object, inside and outside, ability and disability, “I can” and “I cannot.” For Merleau-Ponty, the body schema encompasses a person’s experience of the chiasmic (intertwining) intersection between their fleshly body and the world (142). Constantly reworked and renewed, the mediating, sensing, perceiving, and habit-forming phenomenal body often operates smoothly and hovers imperceptibly in the background. The hidden corporeal schema becomes noticeable when body and world clash, causing a “rupture” (or “misfit”) that demands “reflection” (Fielding, “Habit” 157). For bodies that “misfit,” the “‘I can’ of the habitual body,” which allows the corporeal schema to remain in the background, lingers behind the “I cannot” (Fielding, “Habit” 157). In Diminished Faculties, Jonathan Sterne explores this ambiguous liminal space in which he is unable to determine whether he ‘can’ or ‘cannot’ (18). Bjerke’s art hovers in Sterne’s ‘I don’t know whether I can or cannot’ realm, as the individual pieces and collective installation reveal the hidden/shared unstable tensions of ostomy embodiment: Should I change my ostomy appliance already? Will it irritate my skin more? Have I waited too long to change it?

The strangeness of the nerveless fleshy ostomy; the initial oddity of excrement expelling from one’s abdomen rather than one’s rectum; the crinkly plastic bag hanging from abdominal skin; the awkwardness of changing a leaky bag in a public restroom: these are just a few examples of the “misfits” of re-embodiment after ostomy surgery. Some of these “misfits” become “fits” after time; some remain “misfits.”

Embodiment and the Disabled (Extraordinary) Body: Bjerke’s Ostomy Art

The lived experience of disability and illness can be woven into creative expressions that, intentionally or not, are artistic phenomenological investigations. I turn to Bjerke’s artistic phenomenology of the ostomy, where an opening in the abdominal wall expels waste into an external bag, in which she wrestles with the renegotiation of embodiment after surgical trauma to the body. To dialogue with Bjerke’s misfit ostomy art, I will also draw on my own phenomenological account of touching my newly formed stoma for the first time and the “strangeness” of that touch (Kuppers 1). Both Bjerke’s installation and my narrative disrupt normative views of acceptability, cleanliness, and control, examining a liminal form of embodiment that hovers between inside and outside, and self and other. For Petra Kuppers, bodies are “hinges” that link phenomenological experiences and discourses leading people to “respond creatively” to the “pressures” within these hinged spaces of bodily experience in the world (4). These phenomenological “hinges” of “fits” and “misfits,” which Merleau-Ponty, Garland-Thomson, and Hendren develop in their theories of embodied experience, are the productive creative sites that I will explore through installation art and autobiographical narrative.

Undergoing an ostomy surgery places an internal organ (often the intestine) on the outside of the body. As such, an ostomy resides in a fluid liminal space that slips in between interior and exterior, clean and unclean, acceptable and unacceptable. Bjerke describes her own ostomy art installation pieces as “thoughtful, informative, tasteful, and surprisingly beautiful.” For Bjerke, her “provocative” Hidden Agenda installation probes the reality of “the relentless repetition and inconvenience of an ostomy and its care.” Laying the groundwork for “an otherwise unspeakable topic,” Bjerke’s artistic “dialogue” about her “altered body” opens a space for the discussion of harsh realities and messy re-embodiments that may spark uncomfortableness and embarrassment (xiii). Uncontrollable defecation and the potential leakage of liquid excrement if the barrier ring’s seal gives way often amounts to ostomies being simplistically labeled as ‘gross’ and ‘smelly.’ However, Bjerke’s unexpected use of the words “tasteful” and “beautiful” introduces a positive element to her representation of a medical procedure that is often viewed as an unbearable last resort, frequently provoking an “I would rather die than have a permanent ostomy!” Ostomies and ostomy care can be imprecise, messy, and frustrating, but ostomies can also be associated with beauty and freedom. My first ostomy unchained me from the bathroom. I could leave the house without worrying about diarrhea. I could expel waste on the go. Yes, I had to stop and empty my pouch from time to time, which sometimes signalled a misfit with public toilets, but I felt freer without my ulcerous colon weighing me down with pain and inconsistent bowel movements at inconvenient times.

Time gains a materiality in Bjerke’s installations as the medical supplies and packing materials continue to amass. The “passage of time” connects to a medical abdominal appendage, linking her experience of time with one specific part of her body: her ostomy. I too measure time in ostomy supplies: 2-4 days have passed when I change my appliance (unless a leakage occurs), and 1-2 months have passed when my supplies start to dwindle (depending on how often I change my appliance). The weight of my ostomy pouch tells me if I’ve waited too long to eat, the liquid output sloshing as I move. Physical rectal urgency no longer dictates whether I need to expel waste or not; I simply feel my bag, and judging the puffiness and weight, I empty it.

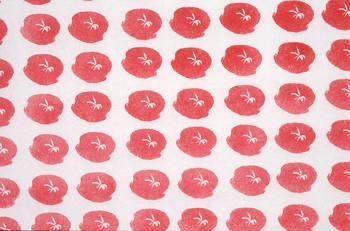

Bjerke writes that her art “is intensely personal and provocative.” Yet, most of her ostomy art focuses on a very specific, small, rose-bud ostomy shape, the generic type of ostomy shown in informational pamphlets to avoid ‘grossing out’ readers. This uniform, rose-bud ostomy shape appears in “Misfortune Cookies” (Figure 1), “Rose-Colored Glasses” (Figure 2), and “Stoma Wall” (Figures 3-5). In its entirety, Bjerke’s installation vacillates between uniformity and uniqueness, provocativeness and the mundane, extraordinariness and ordinariness, rawness and cleanliness, and visibility and hiddenness. The thousands of rose-bud ostomies that dot the installation reveal the common occurrence of a seemingly extraordinary surgical intervention, documenting the thousands of ostomies created each year. To someone unfamiliar with ostomies, the expelling of waste from a surgically constructed hole in one’s abdomen rather than one’s rectum might seem extremely strange and unbearable. But to an ostomate (a person with an ostomy), the strangeness transforms into ordinariness, and I believe that this, along with increased awareness, is the crux of Bjerke’s ostomy art: to understand the simultaneity of the extraordinary and ordinary, cleanliness and messiness, the bearable and the unbearable.

These simultaneities gain a particular materiality in the red polymer clay ostomy “cookies” in “Misfortune Cookies” (Figure 1). Written in the second-person voice, Bjerke’s personal journal entries erupt out of the stoma opening of each clay “cookie.” The long white pieces of paper with varying lengths of black text arch up and out of the stoma opening, curving gently until they reach the neutral-coloured surface of the table. Bjerke’s artist statement reveals that the entries “are transcribed into the familiar second-person voice as a way of communicating information and feelings.” However, the second person “you” also asks the viewer/reader to attempt to identify with the strange looking, puckered, red clay blobs on the table. Bjerke both communicates her feelings through the journal entries and invites her audience to delve into her personal narrative in a very intimate way. An ostomy shape separated from the body foregrounds the extraordinary for a person unfamiliar with ostomies as they become aware of the ordinariness of the ostomy’s everyday function, and the person who accomplishes ostomy care everyday can see the ostomy itself through the lens of the extraordinary. The nearly perfect uniformity of each ostomy “cookie” resists casual medical categorization as the personal entries refuse to be contained within the red clay puckered blob itself.

Although Bjerke does not explicitly state this, the expulsion of the pieces of paper from the stoma opening seem to mimic the (usually) steady flow of ostomy output (excrement), which is a unique and personal experience. The pieces of paper are less messy than actual ostomy output; unlike output that varies in colour and consistency from meal to meal, the paper pieces are clinically white, uniform and defined in shape. Even though the writing on the paper pieces is personal and provocative, the presentation of them spewing from the clay ostomies is, perhaps, calculated to reveal the medicalized nature of the ostomy. Focusing on disability studies and visual art in her article “Unexpected Anatomies: Extraordinary Bodies in Contemporary Art,” Ann M. Fox argues, however, that Bjerke’s “misfortune cookies” “resist photorealism or medicalized documentation” that would “too easily” give way to “voyeurism or revulsion” (88). The red clay “cookies” that remain in a state of undetailed abstraction and the clinical white strips of paper that read personal narratives rather than medicalized text edge Bjerke’s “misfortune cookies” beyond the medical and therapeutic models of disability art (83-84). Creatively calculative, Bjerke’s “cookies” are meant to inform, not to disgust. Although Fox does not explicitly locate Bjerke’s ostomy art within the “activist and aesthetic” models of disability art, the deconstruction of the medical gaze suggests that Bjerke’s art enters this domain.

In Hidden Agendas, Bjerke quotes several notes written on her “misfortune cookies,” requiring the reader to imagine the reality of having an ostomy:

You will be walking across the carpet when your pouch clip lets go and drops down your pant leg, followed by the excrement it had been containing.

will have cleaned the area around your stoma and are drying the skin before attaching a fresh appliance. Excrement emerges from the stoma and soils the skin so you have to repeat the cleaning. And repeat. And repeat. And repeat.

will find that changing the appliance too often is hard on your skin, and not changing the appliance often enough is hard on your skin. And there’s no way of knowing whether it is time to change the appliance without actually changing it.

Although these are frustrating and embarrassing moments, as a person with an ostomy, I find these repetitive instances humorous and exciting to read because they are messy and raw and real. People with ostomies can identify with these “misfortune cookies” that, unfortunately, reveal all too common daily occurrences. Cleanliness can quickly become messiness when liquid output bursts beyond the sticky barrier ring; hiddenness can easily become visible when a leak causes your shirt and/or pants to turn the colour of food you ate last; the bearable can quickly become unbearable when your red irritated skin underneath your appliance itches until you want to rip it off. When you do not have an ostomy, it is hard to imagine all these emotions and sensations wrapped up in a single red blob-like shape, but the words on the white papers accurately describe and accentuate these simultaneities. Bjerke’s cookies are pregnant with small slips of misfortune, inviting us to view the ostomy as a shared, lived experience. The hidden notes spouting from the cookies’ folds announce the hidden agenda of the ostomy: to break the “unspeakable” silence and externalize internal subjective thoughts about the lived ostomy experience.

Image Description: Twelve round red pieces of clay sit grouped on a flat neutral-coloured surface with long thin pieces of paper coming out of the middle of each red clay ostomy “cookie.” The pieces of stark white paper have varying lengths of text printed on them.

Although people without ostomies cannot fully identify with the second-person voice, Bjerke’s work invites them to imagine life with an ostomy. The invisible (or, rather, hidden) intestine that usually remains looped below the skin barrier is exposed, albeit in clay cookie form. As Merleau-Ponty theorizes, the body as a corporeal schema often remains imperceptible. The body moves smoothly, incorporating new gestures as habits and allowing the body to be not just ‘in the world’ but also “toward the world” through inhabitation (103). The body hovers in-between the background and the foreground as a relational entity that constitutes and co-constitutes experience with the world and other people. In these “I can” action moments, in which my body is not physically, emotionally, or socially restricted, I am unaware of all the intricacies of my body’s processes. I eat a salad, and I do not contemplate the progress of my digestive processes. However, with certain illnesses and/or disabilities, pain, motility issues, blockage, and internal surgical scarring, to list a few examples, foreground digestion. In a similar vein, Bjerke’s “misfortune cookies” confront the viewer with images of unprotected intestines visible without the aid of medical imaging, giving us phenomenological glimpses of lived experience with an ostomy. Raising awareness and uniting people with similar experiences, these phenomenological printed snapshots squeezed into crinkled red ostomy openings, unlike the cold objective medical gaze, foreground and personalize the everyday experiences of people with ostomies.

When the mediating, sensing, perceiving, and habit-forming phenomenal body becomes noticeable, as in the case of a newly formed stoma erupting past the skin barrier, the “I can” of the smoothly moving body lingers behind the “I cannot” (Fielding, “Habit” 157). In such an instance, the body experiences a “misfit” which is a contextual, relational, and mediational “juxtaposition,” or a “discrepancy between body and world” (Garland-Thomson, “Misfits” 593). Fielding describes this “rupture” as a demand on our bodies for “reflection” (“Habit” 157). The corporeal schema is forced to renegotiate embodiment. For a person with an ostomy, this renegotiation of embodiment is centred upon a heightened consciousness of a particular section of the abdomen through which the ostomy protrudes. My phenomenal body is thrown into a hyper-aware self-reflexive state. As a vulnerable piece of flesh exposed above the skin envelope, my ostomy becomes a focal point. I mould the barrier ring around this soft, exposed piece of red flesh to protect the stoma, layering the flange on top and sticking the bandage, tape-like on the outer lying skin to provide further adhesion. This plastic, sticky appliance at first feels alien, but eventually it becomes a part of me; I incorporate the appliance into my “body-plus,” which Hendren describes as a constant extension of our bodies into the world (29). For Hendren, “A body is almost never not-extended” (26). However, some extensions are viewed as normative/natural, such as cutlery and cars, whereas other extensions are perceived as extraordinary, such as wheelchairs or guide dogs or ostomy appliances. Since it is attached to my body and I am often aware of its presence, the ostomy appliance becomes more personal than the numerous other instruments incorporated into my daily existence.

Although a physical transformation occurs with an ostomy, the “misfit” that ostomies present is not primarily a physical clash between body and world, such as encountering an inaccessible space. An ostomy is a more nuanced “misfit,” disrupting ableist ideas of body image, cleanliness, and control. After my first ostomy surgery, doctors and nurses enthusiastically emphasized that an ostomy was easy to hide. I felt like I was supposed to hide it. My abdomen was not supposed to bulge out at all. I was not supposed to expose any aspect of my bag in public. I am not supposed to expose my differentness. I was told stories about people with ostomies living completely ordinary lives, doing all the things that they would ‘normally’ do. Often, in normative society, people are expected to control their bowels and wait for an appropriate time to excuse themselves to go to the bathroom. However, with an ostomy (especially an ileostomy), the almost constant flow of fecal matter makes bathroom predictions difficult. The sense of physical defecation urgency is replaced with a purely emotional anxiety since the waste has already left the person’s body and is in the pouch. As an intimate part of my “body-plus,” my ostomy appliance signals a difference that is ‘too different’ and ‘too gross’ for normative society. If I decide to wear a two-piece bathing suit that exposes my scars and my pouch, I will not simply be enjoying a day at the beach or time in the pool, I will be making a statement. My body will not merely be one body among others, falling into anonymity; it will be a different body, an extraordinary body that either sparks awe, amusement, or disgust. My corporeal schema, as with Bjerke’s, is in a constant state of flux, reorientation, and renegotiation as I adjust to a new form of defecation, and as I conform to and resist normative expectations.

Any change to my body will restructure how I inhabit the world, which includes the often-ambiguous transition from the Merleau-Pontian “I can” to “I cannot.” However, as Gail Weiss clarifies, the “I cannot” does not often “lead to an outright rejection of the ‘I can’…but rather, is most often experienced as a tension-filled seesawing between an ‘I can’…and an equally strong feeling that ‘perhaps I cannot’” (79). Jonathan Sterne also experiences this “tension-filled seesawing” between the “I can” and the “I cannot”: “[Merleau-Ponty] is in control enough to delineate the line between ‘I can’ and ‘I cannot.’ I cannot” (18). The shifting, ambiguous in-between space of the ‘I don’t know whether I can or cannot’ reveals the “ambiguities, contradictions, fragments, webs” of a disability/impairment phenomenology (18). The disabled or impaired phenomenal subject is not always sure of itself and cannot be definitively categorized. Sterne’s blunt “I cannot” testifies to this ambiguity. With an ostomy, the “tension-filled seesawing” contains a physical element as Bjerke illustrates in her unvarnished “Misfortune Cookies” notes. Can I walk across the carpet without the seal of my bag breaking and “excrement” soaking my abdomen and running down my legs? Maybe yes, maybe no. Can I know for certain “whether it is time to change the appliance without actually changing it”? Oftentimes, I cannot. If I decide to change my appliance, can I complete the change in a predictable amount of time? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. This constant ambiguous uncertainty, especially when to change an ostomy appliance or how long it will take, is evidenced in Bjerke’s statement, “Excrement emerges from the stoma and soils the skin so you have to repeat the cleaning. And repeat. And repeat. And repeat.” Hovering between “I can” and “I cannot” complete this action, these examples reveal the inherent instability of disability/impairment itself.

The ambiguity between the “I can” and “I cannot,” however, also contains a social normative element: I don’t know if I should do something or not. As I argued above, an ostomy is primarily a normative “misfit” that questions (and challenges) ableist ideology. Initially, I felt like I needed to hide my ostomy at all costs to avoid stigmatization. Can I wear a tighter shirt or dress that accentuates the outline of my bag? To clarify, I am not definitively separating the body and the social environment, as do the medical and social models of disability. Both Merleau-Ponty and Garland-Thomson locate experience at the intersection between the body and the world, and I aim to continue this inclusive approach. An ostomy, as with many disabilities, is a physical impairment with social associations and stigmatizations. Although the social element of an ostomy “misfit” appears primary, the “misfit” itself is an intricate chiasmic interplay between body and social environment.

Normative ableist social conventions are parodied in Bjerke’s piece called “Rose-Colored Glasses” (2005) (Figure 2), which features a similar rose-bud ostomy shape as in “Misfortune Cookies.” Bjerke’s description reads: “Reminder for those who want to look through rose-colored glasses” (34). Five pairs of reading glasses lie on a flat monochrome surface in various positions within the photograph frame, each with a pair of “stoma-shaped plastic additions” plastered on the glass lenses. In their strange chaotic grouped state, as though they have been tossed onto the display table offhandedly, the glasses offer at least four interrelated interpretations: the normative rose-coloured perspective of ableist society, the subversion of the medical gaze, the stoma as a focal point of re-embodiment for a person with an ostomy, and a new lens of awareness and understanding for nondisabled people.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the figurative use of the words “rose-coloured” as “[c]haracterized by cheerful optimism, or a tendency to regard matters in a highly favourable or attractive light” (OED). Often its usage implies that people who look through rose-coloured glasses have an unrealistic view of the world; everything appears idealistically rosy. The ostomy stickered reading glasses remind people who tend toward an unrealistically optimistic view of the world that some things cannot be painted rose-coloured and be given a positive spin. Highly invasive, life-changing surgical operations such as ostomy formations are trauma to the body. One cannot simply dismiss this trauma with a trite ‘At least…’ phrase and all the physical, psychological, (and financial) hardships melt away: At least you’re alive. At least you can hide it. At least you can eat solid food again.

Bjerke’s “Rose-Colored Glasses” also subverts the reductive objectifying medical gaze, foregrounding the mediation of the gaze through the ostomy stickered lenses and suggesting a new type of looking that emphasizes subjective lived experience. In The Birth of the Clinic, Michel Foucault traces the historical transformation of the medical gaze from classificatory medicine, which bracketed the physical body in favour of pathological classification (5), to anatomo-clinical medicine, which reimbued the medical gaze with the tangible thickness of the three-dimensional body through anatomical dissection (200). In anatomo-clinical medicine, the cadaver allows the body to become “transparent” through dissection, whereas life “hides and envelops” the truth of the body and disease (204). Thus, clinical anatomy perception embodies “invisible visibility” (204): invisible during life, but visible after death. In Foucault’s history of medicine The Birth of the Clinic (1963), one begins to see the threads of the myth of transparency that José van Dijck critically analyzes in The Transparent Body. According to van Dijck, medical imaging’s ability to view the inside of the body has “rendered the body seemingly transparent” (x). However, when the increased visualization of the body’s interior is highlighted, the “less visible implications” are thrown into the shadows and forgotten (x). Not every part of the interior of the body is visualizable, and medical imaging itself is often open to interpretation and relies on highly specialized medical practitioners, although in contemporary pop-culture, proliferated by mass media, body scans also become spectacles, viewed by unqualified observers. The ostomy stickers foreground this forgotten mediation of the medical gaze through the supposed transparency of medical imaging. The transparency of the glass is interrupted, and one becomes aware that glass itself is a form of mediation, even though its clarity appears unmediated.

Image Description: Five pairs of glasses (two with black rims and three without) have reddish-pink stoma-shaped plastic stickers on their lenses. They lie on a neutral-coloured flat surface, and a soft light source outside of the picture frame creates interlocking shadows from the glasses’ frames.

The ableist tendency to encounter disability with absolute dread and horror or with an unhelpful optimism that devalues the lived experience of disability reveals the discomfort and stigmatization that accompanies a visible or hidden “misfit.” For Garland-Thomson, the “messiness” of lived experience disrupts the ableist “fantasy” of the “stable, predictable, or controllable” body. The “experience of living” is a series of “fits” and “misfits” that defines humanness (603). Everyone, whether disabled or able-bodied, will have an experience of “misfitting” at some point in their lives. Bodyminds that are different, or perceived as different, will experience more “misfits” than normative bodyminds; however, “the fragility of fitting” means that “[a]ny of us can fit here today and misfit there tomorrow” (597). “Fitting” and “misfitting” is not a static binary but rather a fluid continuum, constantly shifting from a privileged, social position of “material anonymity” to the disruption of an unprivileged position in which “material anonymity” is unattainable (596). The fact remains that, in ableist society, most people prefer stability and predictability and would prefer not to identify as a body that “misfits.” In her artist statement, Bjerke mentions the “active, overjoyed, and smiling” ostomy models in advertisements: “There is no question that many of us living with ostomies routinely do enjoyable things. But this image of extreme ebullience seems insensitive to individual situations, and to the nature of the subject in general” (34). Attempting to show how their ostomy products allow ostomates the freedom to live happy lives, these supply companies tend to dull the gravity of the life-long struggle inherent with an ostomy. The “messiness of bodily variety” that Garland-Thomson writes about can include bodily pain and discomfort (Extraordinary Bodies 23). Bjerke’s “Rose-Colored Glasses” confronts viewers with the constancy of the ostomy, which is sometimes a temporary surgical measure but is often a permanent change to the body. Challenging normate viewers, the rose-coloured ostomies reflect a new lens through which the person with an ostomy views the world.

The treatment of the reality of ostomies as hidden and “unspeakable” experiences is one of the primary themes of Bjerke’s Hidden Agenda installation (19). “Stoma Wall” (Figure 3) is a particularly impactful example of the same rose-bud stoma shape; however, in this piece, Bjerke experiments more explicitly with a juxtaposition between personalization and depersonalization of an “unspeakable” experience. Approximately “75,000 ostomy procedures” (200 per day) “are performed each year” (28). To address “the myriads of anonymous individuals with ostomies,” Bjerke “used a hand-carved rubber stamp to print 210 stomas acknowledging those who were undergoing various types of ostomy surgery that day” (28). For Bjerke, “[t]he ‘Stoma Wall’ is a poignant reminder that even though not much is said about this barbaric practice, it is a fact of life for a significant number of us” (28). In the installation (Figures 4 & 5), long sheets of paper with thousands of stomas stamped onto its neutral-coloured surface line the walls, framing the exhibit and providing a dotted pink/red background for the rest of the installation (including the two previous art pieces). In fact, these sheets simply look like patterned pink wallpaper, until up close one sees the individually stamped stomas (with varying colour densities) appear and confront the viewer with their strangeness. Although the stamp is uniform and exact, the individual stomas that dot the paper strips are slightly uneven at points, some closer together and some further away. This regularity and irregularity of the stoma stamps creates a mesmerizing, almost moving pattern. For Bjerke, the “Stoma Wall defines the installation area, and is a meditation for the myriads of anonymous individuals living with ostomies” (31). The repetitive red ostomy stamp covering the sheets of paper draped on the installation walls directly references the thousands of ostomy surgeries performed each year. One ostomy stamp becomes lost in the thousands of stamps beside, above, and below it; it becomes lost in a sea of red.

Image Description: Several sheets of paper with many roundish red ostomy shapes stamped in neat rows lie partially unrolled on a flat surface.

Image Description: A close-up of the ostomy stamps shows the varying intensity of red ink from stoma to stoma. The white paper peeks through near the center of each ostomy ink stamp to show the intestinal opening of the stoma.

Image Description: Long sheets of paper with hundreds of red ostomy stamps line the wall and lay rolled up on two square metal boxes of different heights.

A “crude and outdated procedure”: The Temporality of Ostomies

Not only does “Stoma Wall” reveal and document the thousands of ostomy surgeries that have changed people’s lives over a few years, but the repetitive generic ostomy shape also comments on the medical/surgical cookie-cutter ostomy formation procedures. In her “Stoma Wall” statement, Bjerke draws our attention to the anonymity of many ostomates as well as “the seemingly mindless acceptance of this practice on the part of scientific, pharmaceutical and medical communities” (28). Bjerke calls the ostomy a “crude and outdated procedure” (xii) that is both “barbaric” and “traumatic” (28). Instead of continuing to accept ostomies as “standard treatment for a variety of gastrointestinal diseases,” Bjerke hopes that “increased awareness will ultimately lead to new solutions” (xii-xiii). As mentioned above, stoma surgery can result from many different gastrointestinal diseases, including colorectal cancer, Crohn’s disease, and Colitis, among others. When non-surgical treatments fail, the stoma is often the next step and the last resort for most patients. Every surgery is a trauma to the body; it is a traumatic (both physically and psychologically) event in which the body is cut while the patient is unconscious and has no control over their body or the surgical team’s actions. An ostomy is a “permanent wound” (Bjerke xii); it is a different kind of “meeting place” between interior and exterior that Petra Kuppers theorizes about skin and scars (1). Bjerke’s ostomy is a “permanent wound” that remains open and unhealed (xii), as are all ostomies. Hopefully, in the future, further non-surgical options will be available. However, as Bjerke recognizes, thousands of people are living with ostomies around the world, and the phenomenological experience of having an ostomy and dealing with the pain, discomfort, messiness, and embarrassment that often accompanies an ostomy should be acknowledged and not simply washed over or diminished. As Bjerke emphasizes, an ostomy is not just a physical procedure, it also affects people psychologically (19).

The body as a “mediator of a world” implies that a person always sees from somewhere, as opposed to the scientific third-person objective gaze (Merleau-Pony, Phenomenology 146). This openness and incompleteness of a person’s horizons/milieus that is grounded through their body schema allows for difference and uniqueness (72). The fluidity and malleability of a shifting body schema that structures and restructures repeatedly reveal the intrinsic universality of the “lived tension” between the “I can” and the “I cannot,” between “fitting” and “misfitting” (Weiss 78, 89). What might be an “I cannot” one day might become an “I can” at a future point in time. Or, as Weiss emphasizes when she engages with Garland-Thomson’s theory of “fitting” and “misfitting,” a “misfit” for one person might be “lived as a fit” for a different person (Weiss 92). In normative society, an able-bodied person might say that they would rather die than have a permanent ostomy, but a disabled person with an ostomy adjusts their engagement with the world through their shifting body schema to incorporate the stoma into their embodied existence. Although other solutions to ostomy procedures would be preferred, the present reality remains that thousands of people live with ostomies and are different and not broken.

Bjerke’s own experiences both dovetail and depart from my own personal experiences with an ostomy. Although an ostomy can be frustrating to take care of and the surgery is traumatic to the body, I personally would not use the term “barbaric” to describe an ostomy surgery. My ostomy surgery made my life 99% better than it was, and even before I knew that I could not undergo an ileostomy reversal, I had determined to never consent to that procedure. The ‘normality’ of returning to defecating out of my rectum did not tempt me to even consider that option. I was readily adjusting to (mostly) less pain and urgency, and the rearrangement of my intestines became less strange with each passing day.

The (Non)Reciprocal Touch

In July 2019, I had my first ileostomy surgery after months of suffering with an autoimmune condition failing medication after medication until there were no other options left. My colon was too diseased to save, inside and outside. The wet, slimy, unclean inside becomes outside and inside simultaneously, clean and unclean, seen and unseen. Laying in a hospital bed preparing my ostomy appliance for the first time, I felt my forearm brush up against the squishy wetness of the new, inflamed stoma protruding from my abdomen. My forearm skin felt the stoma shrink and expand, but the stoma (my stoma) could not feel my forearm. The intestines do not have nerve endings; the stoma cannot ‘feel’ and cannot ‘touch.’ Everything that I learned about my body and sense perception was transformed in that moment: my fingers could feel the wet, soft surface of the intestine, but I did not feel the touch of my finger on my ileum. Here binary distinctions break down: inside meets outside, flesh meets skin, non-touch meets touch— all intertwine and shift in the strange otherness of this non-reciprocal touch. During surgical intervention, the surgeon sews the edge of the intestine to the abdominal skin, and the two surfaces (external and internal) fuse together in the healing process. Unlike Merleau-Ponty’s chiasmic structure of embodiment in which two intertwining threads remain distinct and never fully merge, the fusion of skin and intestine of the ostomy expands the chiasmatic concept: inside and outside fuse yet also remain distinct surfaces.

As Merleau-Ponty argues, there are no binaries or dualities. The most prominent binary that Merleau-Ponty argued against was Cartesian mind-body dualism. For Merleau-Ponty, the mind and body are intricately intertwined just as the body and the world are always interconnected but never fully merged. The “perpetual embodiment” of life is the ambiguous entanglement with the world of “existence” (Phenomenology 169). This continual (re)engagement and (re)structuring of our embodied selves in the process of inhabiting a world with other human beings eliminates the possibility of strict binaries and dualisms. Subject and object; self and other; body and world; mind and body; and inside and outside are fluid, intertwining threads of existence. As in Merleau-Ponty’s explanation of the chiasma, these individual threads never fully fuse together, but they require each other (they are interdependent) through the flow of life.

The strange otherness of my forearm brushing against my nerveless stoma creates a tension for binary systems of thought, such as normative, patriarchal, and heteronormative concepts of able-bodied and disabled, weak and strong, male and female. The inside is now outside; the intestine forms a stoma outside the skin layer, exposed and continuously expelling waste. Does the intestine become part of the outside of the body once it is sewn to the skin as a stoma? Or is the inside simply still the inside but on the outside? Is there a strict binary between inside and outside at all? Merleau-Ponty’s theory of embodiment and his rejection of binaries presents the option of a non-binary idea of the bodily interior and exterior. The body is not simply made up of inside organs and outside layers of skin. It is a complex interplay between all elements of the body (and the mind) in unison. A rearrangement of the intestinal system to expel waste from a stoma is different from the ‘usual’ form of defecation, but the fluidity of the body schema means that I can (re)adjust my form of embodiment and engagement with the world and my own body. However, this does not negate the physical and psychological pain and suffering that occurs after a surgical intervention.

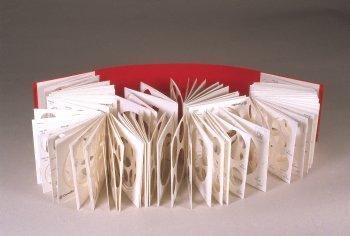

Even if bodily difference can be medically (and socially) categorized, such as the umbrella term ostomy, many different types of ostomies exist, such as ileostomies (end or loop ostomies), colostomies, and urostomies. Within those subcategories, some stomas protrude, some retract, some have more peristalsis, some are large, and some are very small. Every stoma is unique. The beautiful little rose-bud shape is not always what a stoma looks like. Bjerke addresses this difference in stoma size in her piece “How Long Can I Make It?” (Figure 6). Beginning in 2003, Bjerke continued to attach the circular “templates for custom-fitting an appliance” to a piece of red paper in an accordion manner (8). Spread out, the viewer can appreciate the various ostomy sizes which the templates accommodate from 10mm to 76mm. The small red stamp that she used for “Stoma Wall,” representing the quantity and rate at which surgeons create ostomies, must be re-evaluated upon viewing the size range of the stoma templates. “Stoma Wall” acknowledges and represents the thousands of anonymous ostomy procedures done each year, while “How Long Can I Make It?” takes the viewer deeper into the phenomenological realm of the experience of having and taking care of an ostomy. The “permanent wound” that never heals is a constant preoccupation, which requires (as many illnesses/conditions do) that those with ostomies are hyper-aware of a specific part of their abdomen (Bjerke xii, 12). Thus, the constant bodily awareness of an ostomate presents a unique form of embodiment: an inside-outside bodily experience. Even though, as Merleau-Ponty writes, the body is the only way that we can engage with the world as an integral part of it, the phenomenal body itself as a “mediator of the world” (Phenomenology 146) remains the “implied third term of the figure-background structure” (103). The body is not foregrounded; it is “implied,” until something ‘goes wrong’ with it.

When I first accidentally brushed my ostomy, I was fully absorbed with the squishy sensation it produced on my forearm. Only after did I realize how this rearrangement and protrusion of my intestines foregrounded a very specific area of my abdomen. The exposed intestine bleeds easily, and I am hyperaware of not injuring my ileostomy. Itching skin underneath the appliance and increased awareness of peristalsis heightens the foregrounding of this small highly vulnerable area of my body. As my body schema adjusted to this rearrangement, the extraordinary became ordinary, some ‘misfits’ became ‘fits,’ and yet the fluctuating instability of disability experience remains present. Bjerke’s art allows me to view what had transitioned from extraordinary to ordinary as extraordinary again: to realize the simultaneity of the extraordinary and the ordinary. Her critical phenomenological artistic practice hovers in the tension-filled space of subjective experience, revealing the continued need for many types of self-reflexive artistic dialogue in Critical Disability Studies (CDS) and critical phenomenology.

Image Description: White circle templates from boxes of ostomy supplies are folded into an accordion book. A long plain red piece of paper functions as the book cover.

Conclusion

As an embodied phenomenological exploration, art opens a space of intersubjective dialogue that navigates both the accessibility and inaccessibility of embodied experience, preserving the incompleteness and plurality of existence. Reflexivity mingles with self-reflexivity, encouraging viewers to extend beyond ableist tropes and preconceptions of what disability means and to engage with its complexities. Bjerke’s art installation, like disability in general, embodies a unique form of Merleau-Ponty’s “perpetual embodiment” that constantly shifts without equilibrium, requiring a hyper-self-reflexive state. Interrupted in jarring moments before, during, and after surgery, the flow of embodiment undergoes a shifting and reapproximating that affects the body schema and a person’s orientation toward the world. This site of tension between body and world is critical phenomenology’s point of departure, and disabled bodies dwell in these tension-ridden intersections, forcing hyper-awareness and self-reflexivity. In this sense, to be disabled and/or ill means that one is also (un)knowingly a critical phenomenologist. One cannot simply ‘live’; one must examine and reflect upon their embodied experience in order to live.

Weaving moments in time, Bjerke’s art rethinks disability and/or critically ill embodiment as not simply an ever-changing, tension-ridden experience but also as an important avenue of artistic expression. Her ostomy sculptures, stickers, and stamps in Hidden Agenda give mediated presence to the hiddenness of the lived tension between physical disability and subjective lived experience. Art allows creative expression beyond the restrictive ableist binaries of subject and object, inside and outside, ability and disability, "I can" and "I cannot," clean and unclean. When disabled embodiment intertwines with artistic practice, ableist binaries become undesirable and even incomprehensible, requiring both the artist and viewer to examine their own internalized ableism and to imagine life beyond these constructed boundaries.

Endnotes

References

- Bjerke, Carol Chase. “Hidden Agenda: ARTiculating the Unspeakable.” carolchasebjerke.com.

- –. Hidden Agenda:ARTiculating the Unspeakable. Borderland Books, 2008.

- Carman, Taylor. “Forward.” Phenomenology of Perception. By Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Translated by Donald A. Landes, Routledge, 2012.

- Dickel, Simon. Embodying Difference: Critical Phenomenology and Narratives of Disability, Race, and Sexuality. Palgrave Macmillan, 2022.

- Fielding, Helen A. “Introduction.” Cultivating Perception Through Artworks: Phenomenological Enactments of Ethics, Politics, and Culture. Indiana University Press, 2021, pp. 3-23.

- –. “The Habit Body.” 50 Concepts for a Critical Phenomenology. Gail Weiss, Ann V. Murphy, and Gayle Salamon, eds. Northwestern University Press, 2020, pp. 155-60.

- Fox, Ann M. "Unexpected Anatomies: Extraordinary Bodies in Contemporary Art." Critical Readings in Interdisciplinary Disability Studies: (Dis)Assemblages. Edited by Linda Ware. Springer, 2020, pp. 81-92.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. Columbia University Press, 2017.

- –. “Misfits: A Feminist Materialist Disability Concept.” Hypatia, vol. 26, no. 3, 2011, pp. 591-609.

- Grech, Shaun. “Decolonising Eurocentric disability studies: Why colonialism matters in the disability and global South debate.” Social Identities, vol. 21, no. 1, 2015, pp. 6-21.

- Hendren, Sara. What Can a Body Do?: How We Meet the Built World. Riverhead Books, 2020.

- Kuppers, Petra. The Scar of Visibility: Medical Performances and Contemporary Art. University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

- Lajoie, Corinne. “Being at Home: A Feminist Phenomenology of Disorientation in Illness.” Hypatia, vol. 34, no. 3, 2019, pp. 546-569.

- –. “The Problems of Access: A Crip Rejoinder via the Phenomenology of Spatial Belonging.” Journal of the American Philosophical Association, vol. 8, no. 2, 2022, pp. 318-337.

- Meekosha, Helen. “Decolonising Disability: Thinking and Acting Globally.” Disability & Society, vol. 26, no. 6, 2011, pp. 667-682.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Donald A. Landes, Routledge, 2012.

- –. The Visible and the Invisible. Translated by Alphonso Lingus, Northwestern UP, 1968.

- Nielsen, Emilia. “Chronically Ill, Critically Crip?: Poetry, Poetics and Dissonant Disabilities.” Disability Studies Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 4 (2016), pp. 1-24.

- Reynolds, Joel Michael. The Life Worth Living: Disability, Pain, and Morality. U of Minnesota P, 2022.

- –. “The Normate.” 50 Concepts for a Critical Phenomenology. Gail Weiss, Ann V. Murphy, and Gayle Salamon, eds. Northwestern University Press, 2020, pp. 243-48.

- –. “The Normate: On Disability Critical Phenomenology and Merleau-Ponty’s Cezanne.” Chiasmi International: Trilingual Studies Concerning Merleau-Ponty’s Thought, vol. 24, 2002, pp. 199-218.

- "rose-coloured | rose-colored, adj." OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2023, www.oed.com/view/Entry/167530. Accessed 13 April 2023.

- Sterne, Jonathan. Diminished Faculties: A Political Phenomenology of Impairment. Duke University Press, 2021.

- Titchkosky, Tanya. Disability, Self, and Society. University of Toronto Press, 2003.

- –. and Rod Michalko. “The Body as the Problem of Individuality: A Phenomenological Disability Studies.” Disability, Space, Architecture: A Reader. Routledge, 2018, pp. 127-142.

- Weiss, Gail. “The normal, the natural, and the normative: A Merleau-Pontian legacy to feminist theory, critical race theory, and disability studies.” Continental Philosophy Review, vol. 48, 2015, pp. 77-93.