(In)visible journeys: experiences of students with disabilities

Le parcours (in)visible : L’expérience d’étudiants en situation d’handicap

Alfiya Battalova

Assistant Professor in the School of Humanitarian Studies

Royal Roads University

alfiya [dot] battalova [at] royalroads [dot] ca

Aleksandra Kovic-Bodiroza

Royal Roads University

aleksandra [dot] kovicbodiroza [at] royalroads [dot] ca

Anu Pala

Royal Roads University

hello [at] anuvision [dot] ca

Margarita Jarrin

Royal Roads University

margajarring [at] gmail [dot] com

Royal Roads University

alfiya [dot] battalova [at] royalroads [dot] ca

Aleksandra Kovic-Bodiroza

Royal Roads University

aleksandra [dot] kovicbodiroza [at] royalroads [dot] ca

Anu Pala

Royal Roads University

hello [at] anuvision [dot] ca

Margarita Jarrin

Royal Roads University

margajarring [at] gmail [dot] com

Abstract

This mixed-methods study explored the experiences of disabled students at a small postsecondary institution in Canada, using data collected through surveys and focus groups. The research project sought to examine attitudinal and educational barriers and the impact these barriers have on students’ experiences. Informed by critical disability studies concepts of (in)visibility, crip time, and intersectionality, the study found that accessibility is complex and shaped by diverse needs, stigma, and systemic obstacles such as inconsistent instructor engagement and inflexible online learning platforms. The study underscores the need for holistic and responsive approaches to truly inclusive education.

Résume

Cette étude à méthodologie multiple explore les expériences des étudiants en situation d’handicap grâce aux informations recueillies par moyens de sondage et groupe de discussion dans une petite institution d’enseignement postsecondaire au Canada. Ce projet de recherche a pour but d’examiner les barrières aux niveaux de l’éducation et de l’attitude, ainsi que leurs impacts sur l’expérience des étudiants. Se basant sur les concepts des études critiques du handicap sur l’(in)visibilité, de temps du handicap et d’intersectionnalité, cette étude montre que l’accessibilité est complexe. Elle est concrétisée par des besoins divers, des stigmates et des obstacles systémiques comme l’engagement inconsistant des instructeurs et instructrices et l’inflexibilité de plateformes d’apprentissage en ligne. Cette étude met en évidence le besoin d’une approche holistique et réceptive pour une éducation véritablement inclusive.

Keywords: (In)visible disabilities; Crip time; Relationality

Mots-clés : Handicaps (in)visibles; temps du handicap; relationalité

Background

The paper focuses on the experiences of students and alumni with (in)visible disabilities in their post-secondary journey at a Canadian university. Despite the willingness of institutions to offer mandated support, there is a lack of knowledge and understanding among different communities on university campuses about the needs of students with (in)visible disabilities. Faculty often show a lack of positive attitudes (Kerschbaum et al., 2017). Such attitudes lead to unfavourable experiences for students with hidden disabilities, resulting in feelings of marginalization and exclusion as well as decreased academic performance (Benkohila et al., 2020; Lindsay et al., 2018). Addressing these attitudinal barriers is crucial for fostering an inclusive and supportive academic environment. The system that is characterized by ableism and sanism are entrenched in neoliberal policies and practices that make the experience of disability more difficult and conditions the solutions within individualized capacities rather than within larger system-wide or structural reforms (Shanouda & Spagnuolo, 2021).

Legally, higher education institutions are obligated to provide reasonable accommodations upon request and submission of satisfactory proof of disability. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006) outlines the aims of the right to education. These aims include ensuring the full development of human potential, dignity, and self-worth and each student’s personality, talents, creativity, and mental and physical abilities. On a provincial level, accessibility legislation has initiated discussions about developing the postsecondary education standards (Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility, 2022).

However, legislation is in place for persons with disabilities for some Canadian provinces, and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms specifically names disability as a protected status. At the same time, legislation does not necessarily shift attitudes to ensure persons with disabilities feel included. There is a difference between providing an accessible space and feeling welcome in the space (Doyle et al., 2023).

According to The State of Postsecondary Education in Canada report (2023), the proportion of students who report having a disability/impairment in Canada has been increasing steadily whether because more students with disabilities were accessing education or because of a reduced stigma in disclosing disabilities (or both). In 2016, the Canadian University Survey Consortium survey about the first-year students in Canada that the above-mentioned report is based on changed the question about disability to explicitly include mental health issues. As a result, the proportion of self-reporting students shot up to 22%. By 2022, this figure had reached 31% (Usher & Balfour, 2023). This increase has not kept up with the level of services, supports, and the overall knowledge we have about navigating post-secondary education with these conditions. Research shows that the current accommodations model is an inefficient use of disability resources (Hills et al., 2022) that mostly focuses on mandating extra time. The concept of time has been explored in critical disability studies using the concept of “crip time.” Crip time does not just recognize the temporal nature of how the medical field talks about disability (e.g., “incidence,” “occurrence,” “remission”) but also foreground crip time as an essential component of disability culture and community (Kafer, 2013). Crip time is an adjustment to a slower gait that makes it longer to get to a destination, a recognition of the reliance on external factors like assistive devices and care attendants, or an ableist encounter that adds extra time to the day. In the post-secondary contexts, crip time can mean an extra time on exams, but more importantly it offers a potential for challenging the normative expectations around pace and scheduling. Samuels (2017) describes crip time as a way to adjust our bodies and minds to new rhythms as well as new patterns of thinking, feeling, and moving through the world. It is about listening to the language of our bodyminds and honoring them.

Research shows that the use of specific academic accommodations, such as extended time or exam modifications, significantly increase disabled undergraduates’ GPA and fostered graduation (Kim & Lee, 2016). Yet, only 35% of undergraduate students who were identified as disabled in high school decided to self-disclose to their postsecondary institution (Newman & Madaus, 2015). At the institutional level, higher education requires and promotes able-bodiedness and able-mindedness (Dolmage, 2017). As a result, disabled students’ needs remain invisible. The study’s framework is informed by the idea of (in)visibility. We conceptualize (in)visibility as an ambivalent and contested category that is shaped and reshaped through individual experiences, institutional policies, and broader societal discussions. “Hypervisibility” in the context of disability invokes the idea of staring, being remarked on, noticed, a concept that has been explored extensively in disability studies literature (Garland-Thomson, 2006; Spirtos & Gilligan, 2020), On the contrary, invisibility discourses bring up the discussions about faking and invalidation of disability experiences. What is often missing in these accounts is ambivalence (Battalova et al., 2022) that highlights the very instability of the category of disability. Disability resists identification through classification because of its instability and particularity rooted in an arbitrary and incomplete process of categorization that is also profoundly influenced by cultural differences (Samuels, 2014).

For example, even people who are considered visible disabled might experience a myriad of invisible challenges (e.g., chronic pain, mental health) that they are not able to convey due to a medicalized understanding of disability. As Brueggemann et al. (2001) suggest,

This is the paradox of visibility, another of disability culture’s great concerns: now you see us; now you don’t. Many of us “pass” for able-bodied—we appear before you unclearly marked, fuzzily apparent, our disabilities not hanging out all over the place. We are sitting next to you. No, we are you. As the saying goes in disability circles these days: “If we all live long enough, we’ll all be disabled. We are all TABs—temporarily able-bodied.” We are as invisible as we are visible. (p. 369)

Davis (2005) writes that “the visibility or invisibility of a disability is something that is determined by the ease of its perception by others, not by its impact on the persons with the disabilities” (p. 203) and ultimately concludes that the social response to those who have invisible disabilities is inadequate and it gives us a good reason to suspect that our commonsense notion of disability itself is fundamentally flawed.

While recognizing the unique needs of students with invisible disabilities, our project is trying to challenge the medicalized divide between what is considered a visible and an invisible disability. The experiences of (in)visibility are common for all people who do not fit the norm. Bodyminds (a neologism proposed by Price [2011] as a way to challenge the separation between physical and mental disabilities) are made invisible as a result of their belonging to marginalized groups (Rajan‐Rankin, 2018; Welle et al., 2006). Pieri (2019) argues that disabled subjects are embedded in systems of power that mark them as deviant and create the political, social, and cultural conditions of invisibility in which they are positioned. In a post-secondary setting, all disabilities on college campuses are invisible—until an accommodation is granted, they have no legal reality (Dolmage, 2017). As Dolmage writes,

So-called invisible disabilities are particularly fraught in an educational setting in which students with disabilities are already routinely and systematically constructed as faking it, jumping a queue, or asking for an advantage. The stigma of disability is something that drifts all over—it can be used to insinuate inferiority, revoke privilege, and step society very freely. (p. 10)

Dolmage demonstrates that (in)visibility of disability and the inherent distrust of people who identify as people with invisible disabilities makes it particularly challenging. Because disability is objectified, it is not seen as an identity, perceived by others additively rather than intersectionally and holistically. Abes and Wallace (2018) argue that students with disabilities are invisible on campus because others see their disability only as a need for an accommodation rather than as an identity, let alone an intersectional identity. Treating disability as a social identity means recognizing it as a socially constructed aspect of a person’s self that intersects with other social identities.

The research project sought to explore attitudinal and educational barriers and the impact that these barriers have on students' experiences. The project also aimed to collect feedback on what can be done to improve accessibility at Royal Roads University (RRU) in British Columbia, Canada. RRU delivers on-campus and online programs. While e-learning provides multiple opportunities for disabled students to pursue postsecondary education, it also presents multiple challenges. More specifically, one of the challenges lies not only in identifying the accessibility needs of students but also in integrating these features into Learning Management System (LMS) platforms in a way that is both functional and user-friendly. Kent (2015) writes that part of the problem related to accessibility through Moodle (that RRU relies on) is that as each person designing a course sets out their own Moodle web interface. Often operating without an existing accessible template these are then constructed in a way that prevents assistive technology such as screen readers to navigate the page.

British Columbia introduced an Accessible BC Act which required public organizations—including post-secondary institutions—to establish an accessibility committee, develop an accessibility plan, and introduce a feedback mechanism. While we recognize that the pace of implementing the changes resulting from the legislation is slow and might not result in new policies and practices, it is an important contextual background that highlights the need for changes. For the purposes of the study, we intended to explore how the undergraduate students experience interaction with systems and services at the university.

Methodology

The paper is a mixed-method study that uses a survey and focus groups. Both methods were launched concurrently with focus groups recruitment taking more time. The study was approved by the Royal Roads University’s ethics office. The recruitment of the students was conducted with support from an accessibility office that shared the poster for the study with current undergraduate students who are completing an on-campus or online program. The language of consent was included in the preamble of the online survey developed in Office 365 Forms. The implied consent used in the survey means that participants agree to participate by completing the survey, rather than signing a separate consent form. The survey respondents were entered a draw to win one of five $50 gift cards.

A total of 74 survey responses were collected, and two focus groups with 10 students and alumni with disabilities were conducted. The focus group participants were recruited from the same people who received an invitation to participate in the survey, however due to the survey privacy, we do not know how many people both completed the survey and participated in a focus group.

Below is a breakdown of some of the survey respondents’ demographics.

Table 1. Survey respondents’ demographics

| Women, Trans, and Nonbinary[1] | 50 |

| Non-white | 21 |

| International student | 7 |

| Currently enrolled | 17 |

| Have more than one disability | 41 |

| Total | 74 |

The survey and focus group questions included questions like the following:

- “Can you describe your experiences commun icating your accessibility needs?”

- “How can support staff, including instructors, improve their knowledge and understanding about accessibility?”

- “What supports you wanted to receive during your time as a student, but did not?”

The analysis was driven by the reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2019).

Focus group discussions offer the potential to engage with students as partners and surface a more authentic voice. Conducting discussions in groups, as opposed to individually, allows for the observation of group dynamics, providing insight into why individuals may agree or disagree on perceptions or ideas and providing a space for the generation of new ideas (Bourne & Winstone, 2021; Kroll et al., 2007). As well, participants have more time to reflect and to recall experiences, especially in response to other group members who comments can trigger recollection and reflection (Lofland et al., 2006). We organized two focus groups of past and current students who could share more in-depth, qualitative stories using a semi-structured approach. We provided honoraria for participation in focus groups.

We applied a reflexive and intersectional analytical approach to this project informed by critical disability studies (CDS), specifically the notions of power, materiality, and intersectionality (Meekosha & Shuttleworth, 2009). For example, in line with the CDS idea that a human identity is multiple and unstable, our conceptualization of (in)visibility as inherently unstable category influenced our approach to recruitment. We did not set any diagnostic criteria allowing any students or alumni who relate to the category of (in)visible disability to participate.

Within reflexive thematic analysis, the coding process was integral to theme development, but coding was not a process for finding evidence for pre-conceptualised themes. Instead, the analytic process involved immersion in the data, reading, reflecting, questioning, imagining, wondering, writing, retreating, and returning (Braun & Clarke, 2021). All the research team members had (in)visible disabilities, and some were former students of the university. These experiences helped inform the analysis by paying more attention to the interaction between the particular structures and policies and the students’ experiences. Considering multiple ways that identities interact, students with disabilities often reveal how intersecting systems of oppression result in them struggling for a sense of wholeness, negotiating others’ perceptions, and managing how oppression shapes their higher education experiences (Abes & Wallace, 2018). The intersectional experiences of disability, gender, immigrant status, race, and ethnicity of the researchers informed the analysis of data.

Findings

The reflective thematic analysis revealed the three themes. The quantitative findings provide a strong empirical foundation for the qualitative data collection that focused more on how students made sense of their experiences.

Unpacking the Complexity of Accessibility

The participants expressed diverse perspectives on what accessibility means. Some participants noted that accessibility is about making changes in the LMS platform (for example, updating the due dates for students with accommodations who might be seeing that their assignments are overdue because the dates, resulting in increased anxiety and a feeling of being “less than”).

And I'm allowed to have that time, just to see it late. I just I couldn't even go in to look at Moodle to see when these, because it just it's such an anxiety driver for me. So I'm glad that I wish more professors would do that where they would go in and change the date. Pending any confusion that that can cause for others. I think that's a really big deal, and that would have, I think, eased some of my anxiety that I had for sure (EH).

In navigating the system to secure supports, international students with disabilities commented on the labeling and stigmatizing nature of the term “disability” that they have a hard time embracing when asking for help. Accessibility can be related to access to food and adequate housing as well as financial support. When thinking about wraparound supports and services, students with disabilities understand the need for holistic approach.

Throughout the focus groups, participants shared seemingly contradictory ideas. Some felt that it was important for them to take ownership of the accommodations process, to be better self-advocates. They did not view their role in educating staff and faculty as a burden. They did not mind playing that role. In arguing for being more proactive, these students wanted to have a choice not to approach an instructor, not to be singled out. At the same time, some felt that they might not even know what they can ask for, what is available for them. In that, these students wanted the post-secondary institution to take more responsibility.

I've learnt to explain my disability and own it, explain it, take responsibility for it, and get support in things I need support in… I don't know if I'd want to be singled up by an instructor even after the letters been given, so I'm almost wondering if there could be a thing for students. Okay, this is what you want included in the letter. Right? So yeah, I'd like the to approach the instructor, or I would like this, or I would like that (JM).

For those who are still learning how to navigate the system, knowing what they can ask for is helpful:

Nobody's really accommodated me in my life until I came to Royal Roads, and so I don't even know what to ask for, or what would be helpful beyond some of those coping strategies that I use (KS).

Ultimately, the learning process is not about assessing what style of learning is better.

It's just like if we try to push people back into this one box and say, this is the way you have to do this. This is when you know you get the slap on the face, and you feel like something is wrong with you, because you're measured on a standard that you just can't achieve…then it's upsetting, because then we are faced with a language that says, something is wrong with us, and like there's like something that is lacking (TP).

TP is reflecting on the failure of the standardization and comparison to respond to the needs of those who can never achieve this “standard.”

There is never going to be an agreement on what accessibility means when applied to individual experiences. Considering the variation across bodymind experiences and the very instability of the concept (in)visibility, it was not surprising to see the different definitions of accessibility. It can be about the responsive systems that do not expect students to constantly self-advocate, it can be a mix of self-advocacy and a system that does not have a standard for what supports can be provided because it forecloses the opportunity to be flexible when someone’s need within their (in)visible disability is not traditionally anticipated.

Practices of (In)Visbility

The liminal nature of invisibility is reflected in how participants discussed their interactions with instructors. It was not consistent in terms of whether instructors reached out once they received a letter of accommodation asking students to provide any other information that might improve their experience in a classroom. Oftentimes, the students do not hear from the instructors during the course. This sense of unpredictability was conveyed by a student:

I only ever had one professor connect with me, overtly saying, Hey, we got your letter. Let me know if there's anything you need…So I thought that was interesting. Given I've taken like 30 courses (RH).

Some students spoke of administrative miscommunication that often resulted in instructors not having information about a student’s accommodations. While the administrative staff of each program usually sends the accommodation letters to the instructors, there are stories of breakdowns in this process. The instructors who teach at Royal Roads University are often contract faculty, and they are often hired very close to the start of the course. Others simply do not have enough knowledge about accessibility, thinking that accommodations letter is sufficient in terms of addressing the students’ needs. While extended time on assignments might be what the letter requests, it does not promote a relational approach that many students would like to have.

Whoever the administrative body is that gets that letter doesn't pass it off to the instructors. There's always a disconnect (RH).

There is an inconsistent approach to accessibility among different instructors.

I had 2 professors in the same course. One would give me transcripts and everything else, and the other wouldn't budge, wouldn't do anything, and I don't understand it (AZ).

The same student requested minimizing background noise and ensuring that closed captioning is available, and despite the instructor’s promise, the changes have not been made.

Ironically, invisibility can have a positive connotation. A student shared that sometimes they do not even need to enact their accommodations because some instructors incorporate the Universal Design in Learning (UDL) principles. Disability becomes both hidden but also recognizable because the instructor proactively embraced different learning styles.

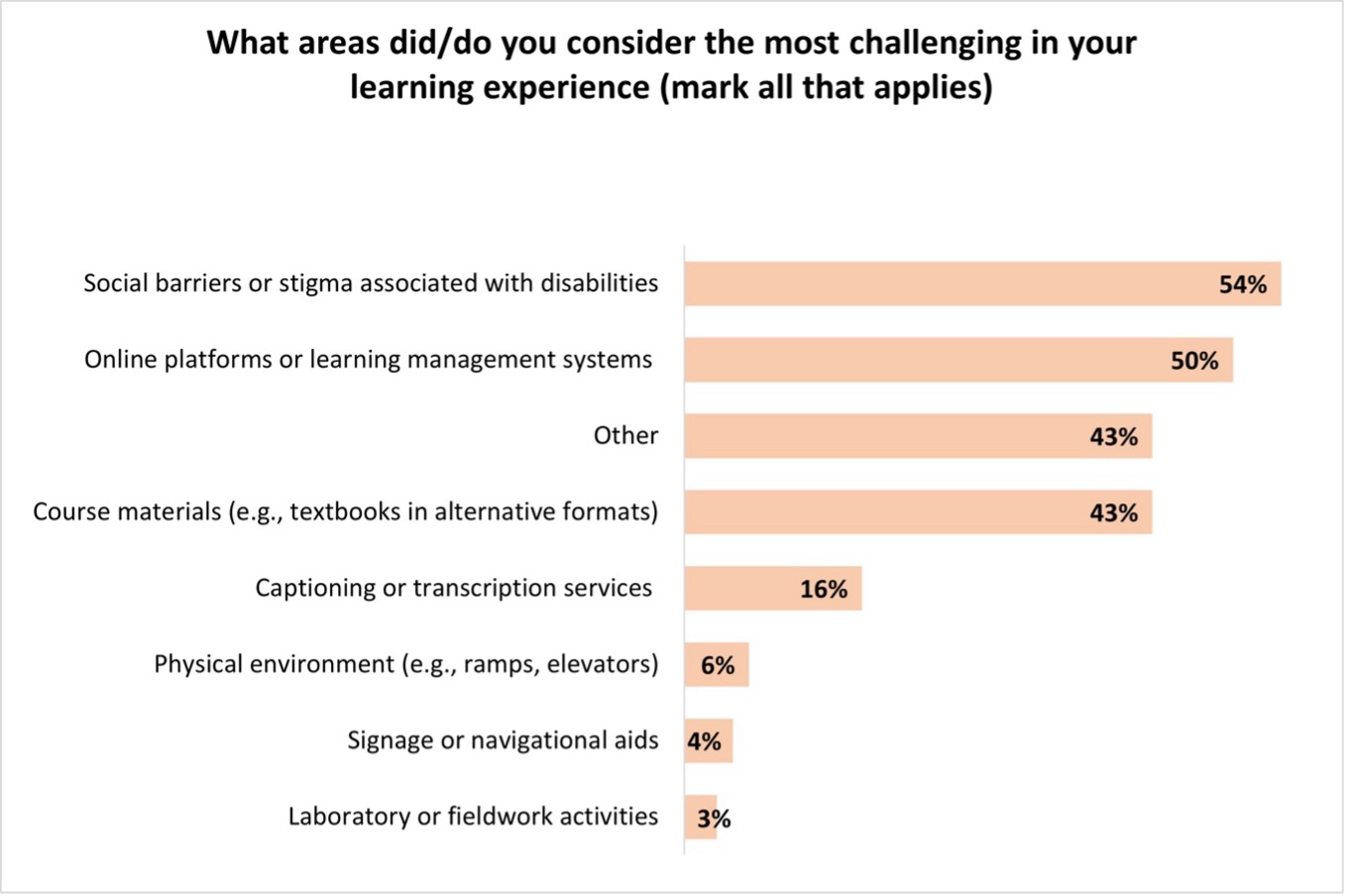

The practice of (in)visibility are discussed in more detail in the survey. When asked to describe the barriers they experienced in their educational journey, the main barrier was social barriers or stigma (54%). The fact that every second student reported this to be their number one barrier suggests that (in)visibility functions as both an internal characteristic and an unstable identity as well as a societal attitude. Disabled people are made to feel invisible through a practice of minimizing or de-valuing of their experiences.

The next most frequently reported barrier is an online course platform (50%). This is not surprising provided that Royal Roads University delivers a significant number of courses online and the inconsistent approach to accessibility within the LMS. Among other barriers mentioned are inconsistencies in delivery of programming when some courses were very accessible and others had a lot of barriers. Respondents also mentioned varying levels of understanding of accommodation among instructors.

Figure 1. What areas did/do you consider the most challenging in your learning experience?

Description: A bar graph that reflects the responses to the question “What areas did/do you consider the most challenging in your learning experience (mark all that applies).” Social barriers or stigma associated with disabilities and online platforms or learning management systems had the most responses (54% and 50% respectively).

(In)visibility is prominent in students’ stories in not being seen by the instructors beyond the accommodation letters. Extended time on assignments is the most common type of accommodation as the survey results demonstrate. Time is a critical component in the structure of today’s postsecondary institutions. The duration of the course and the expectation how long a student can learn about a specific subject matter and deadlines for submitting the assignments place very normative definitions around learning. While providing extensions can be seen as the easiest way to ensure students are able to keep up with the pace of learning, its wide use poses a larger question about time and learning and the ways in which a concept like crip time can challenge that.

Between the Systemic Barriers and Opportunities for Change

The focus group participants commented on the bureaucracy being one of the significant barriers in a postsecondary environment. In addition, participants were aware that many of their instructors are contract faculty who have limited capacity to integrate the UDL principles in their teaching, to reach out to students to discuss their accessibility needs (beyond letters of accommodations) and build their knowledge and skills in the area of accessibility. Reflecting on his experience working with contract faculty in a support role at a different institution, one student commented:

I have 400 students in that class, and I'm teaching 4 sections in one term. And [instructors] want to be on board, but logistically, how do they manage their capacity, their limited capacity? (SK)

Despite recognizing the challenges of addressing these barriers, the participants provided ideas for re-imagining the approaches to accessibility through creating opportunities for open conversations when the issues of accessibility can be discussed between a student and an instructor instead of being looked at from a bureaucratic, non-relational approach. Relationality is a way to challenge the traditional approaches. One participant suggested an informal approach where it is normalized for instructors to ask about what they can do to support the learners.

Just to have that not like a meeting group. But say, hey, like, Tell me what this is like for you, or how can I best support you? (EH)

Ultimately, the change can start with what one participant called “wise practices” (different from best practices):

There's a difference between wise practices and best practices. So best practices are based on evidence and are essentially a past practice, whereas wise practices are what we, as a community and practitioners that support people with disabilities would be recommending (KS).

These wise practices are rooted in empathy. Fully recognizing the slow pace of changes and the imperfect nature of the policies, empathy and understanding were mentioned as good starting points. The concept of wise practices can contribute to the discussion about moving from an accommodation to an accessibility approach through a relational component when an individual needs are not forced into narrow boxes of what is possible but embraced as an opportunity for creativity, deeper connections, and new ways of envisioning learning.

Interestingly, participants mentioned that compliance or a checklist is not necessarily a bad place to start. The important thing is that it cannot be where the conversation about accessibility ends. In support of the qualitative findings, the survey respondents shared that what could help make the classrooms (in-person and virtual) more accessible, they mentioned things like extended timelines or very clear communication about the deadlines, less bureaucracy when navigating funding for more supports, and patience and understanding, something that focus group participants discussed as well.

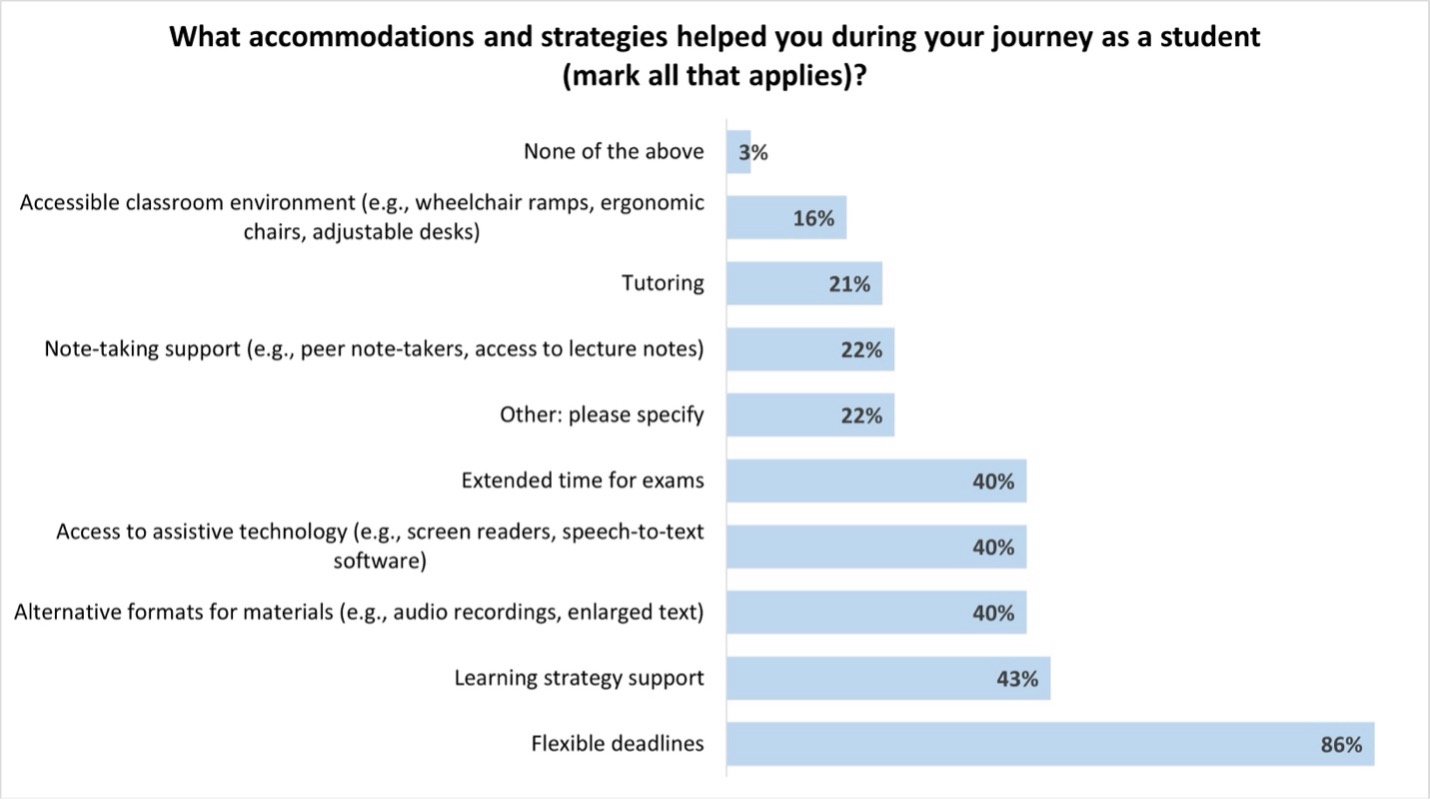

Figure 2. What accommodations and strategies helped you during your journey as a student?

Description: a bar graph that reflects the answers to the question “What accommodations and strategies helped you during your journey as a student (mark all that applies)?” The most popular response was flexible deadlines (86%). The other popular responses were learning strategy support (43%), alternative formats (40%), access to assistive technology (40%), extended time for exams (40%).

By asking survey respondents about the accommodations and strategies that helped them (Figure 2), we wanted to hear about both official accommodations but also personal strategies and tools. For example, many people with sensory disabilities might be using their personal assistive technology that they are used to and that they are most comfortable using. Flexible deadlines were the accommodation mentioned as the most helpful by 86% of respondents.

When asked to describe their experience communicating their accessibility needs to the instructors, respondents did not just comment on whether the communication resulted in their accessibility needs being met. They shared the nuances of this communication that shed light on the importance of clear expectation from a program as a whole (not just an individual instructor) from the start, more responsiveness and engagement in the issue from the instructors, and the need not to have to share the accommodations with every new instructor.

The top three recommendations related to the changes or improvements that students or alumni suggest making for the academic environment to make it more inclusive and supportive for students with disabilities include the following:

- Establish a dedicated disability support office to coordinate accommodations and provide resources (78%)

- Increase awareness and understanding of disabilities among faculty and staff (71%), and

- Provide training and resources for professors on accommodating students with diverse needs (67%).

This theme recognized that despite the significant structural barriers, small and meaningful improvements can be made. A lot of the courses taught at Royal Roads University are online. More can be done to ensure the setup of the courses in LMS is improved in terms of the layout, integration of captions in the videos/podcasts, accessible layout of PDF and other documents, image descriptions, etc.

Discussion

The analysis of survey and focus groups demonstrated that (in)visibility of student experiences is reflected in several ways—from how it is defined to the kind of systemic barriers surrounding the system of academic accommodations. Although the issue of having to provide documentation has not come up for the participants in our study, the medicalized approach to disability is another important systemic issue that cannot be ignored. Students, especially those who do not have a diagnosed disability, are required to provide a medical documentation which is usually accompanied by an expensive and often unaffordable assessment process.

In using (in)visibility as a conceptual category, we gave voice to the current and former students who do not always feel like they are heard. In invoking this category, we want to agree with Davis (2005) who writes,

If we are interested in trying to understand disability, and in trying to formulate disability policies that are both adequate and morally sensitive, we would do well to recognize that energy expended in the attempt to isolate “the facts” of disability from the prevailing moral and social attitudes that influence our understanding of the meaning and salience of these facts is energy misdirected (p. 155).

In other words, the stories of our participants focus on the tangible experiences that such misdirected attempts result in. Instead, more efforts could be made on removing structural barriers, specifically cultural biases that still prevail in the societal perceptions of disability.

Participants shared that extended time for exams and flexible deadlines are the most helpful accommodations for students with (in)visible disabilities. One of the ways in which normative idea of time can be disrupted is crip time, which denotes different temporalities by which disabled people live their lives (Kafer, 2013). Crip time may be slower, non-linear and generally more fluid and flexible (Rodgers et al., 2023). The prescribed timelines fail to account for the many reasons why disabled students' experiences may not align with the normative expectations. Crip time in the context of higher education offers the potential for crip futures in which disabled people can live authentically. Crip time reveals how expectations about pace maintain ableist norms. Timed testing, assignment timelines, and classroom participation are rooted in an assumed pace of a nondisabled student. Crip time in practice rejects the scripts of laziness placed on disabled students, flipping the onus onto educators to examine and transform their practice (Abrams et al., 2024).

A thoughtful course design and a sense of psychological safety were mentioned by the survey respondents as ways to address ableist classroom practices. Communities of practice that can be built across departments, units, and universities were recommended as another solution by the focus group participants.

Self-advocacy was discussed as an important tool to use in the students’ accommodations journey. But this approach expects students to have knowledge of the complicated system and what it can offer. One of the issues that some students, especially with recent or undiagnosed disabilities might experience is not knowing the mandates of university offices and how to navigate the system. Yet, it is an essential element to demonstrating legal inequality or the absence of appropriate accommodation (Jacobs, 2023).

Yes, this option is not available or feasible to everyone. The bureaucratic nature of the system disempowers and provides no guarantee that things will work the way they are expected to.

Insofar as ‘people with disabilities’ can be noticed and understood as ‘the same as’ any other potential participant but still excluded unnecessarily, or excluded through no fault of our own, bureaucratic measures are developed to address this problem of excluding those deemed to be the same as any other includable type. (Titchkosky, 2011, p. 94)

In other words, a system builds on complex processes and procedures will unavoidably exclude and result in some people falling through the cracks. The reliance on contract faculty is one aspect that is rarely explored in terms of how the conditions in which instructors work are not conducive to providing accessible course delivery. Within education, we see neoliberalism’s effects in the reduced funding and corporatization of universities and colleges, and in the influences of market rationalities on planning, investment, and implementation (Shanouda & Spagnuolo, 2021). The neoliberalization of institutions and the proliferation of reliance on precarious adjunct workforce in higher education (Gagnon, 2022) resulted in the reduction permanent staff and faculty and reliance on contract staff and faculty.

In the study of contract faculty and the accessibility needs of neurodivergent students, Faure and Sasso (2023) found that the lack of understanding and limitations of the contract responsibilities prevented contract faculty from ensuring accessibility for neurodivergent students. A failure to secure some of the accommodations, such as access to readings a few days before the start of the course is directly related to often last-minute hiring of the faculty that leaves minimum or no time for them to provide the readings in accessible format before the start of the course.

Disabled students recognize the importance of addressing the attitudinal and cultural barriers first. Most of the recommendations focused on providing training and increasing awareness among instructors as well as adopting more proactive approaches, such as Universal Design in Learning (UDL). For example, disability funding could be better directed to more proactive initiatives, such as a paid, full-time UDL coordinator who could provide sustained help to faculty wishing to make curriculum changes, addressing, at least in part, some of the time and resource constraints that faculty experiences (Hills et al., 2022). There is also recognition that change, such as a wider role of UDL, requires a positive strategic collaboration and alliances amongst key players within institutions from the top-down and bottom-up.

The study explored the experiences of disabled students at a small university and invited them to reflect on their experiences and re-imagine a more accessible postsecondary experience. In addition to conjuring up a non-medicalized approach to accessibility, the students also provided suggestions for change both in classroom and at the institutional level.

Limitations

The study included the students who requested services from an accessibility office; thus, they had some sort of an official diagnosis. Accordingly, the study automatically excluded students who might have an (in)visible disability but could not secure a documentation. Unfortunately, given the limited time we had for data collection and the parameters of the ethics approval, we could not expand our recruitment efforts. In addition, in line with the idea of normative time expectations, we could not run more focus groups or extend the survey data collection limiting the amount of data we collected.

Limitations

Our study brings into conversation multiple concepts of critical disability studies, such as (in)visibility, crip time, and intersectionality providing a strong empirical foundation for how these concepts can be applied in a context of an undergraduate student experience. Future research can look more closely at what wise practices can look like. Other questions that are important to explore focus on how to bridge the gap between the structural rigidity of postsecondary institutions with a call for more relational approach to accessibility. Finally, in a context of neoliberalism that often relies on precarious labour of contract faculty, it is important to understand how they can be supported and not blamed for the inherent gaps in the system.

Conclusion

This study highlights that accessibility in postsecondary education is far more than a set of technical accommodations or compliance checklists—it is a dynamic, relational process shaped by individual experiences, systemic structures, and social attitudes. The findings show that while some students value self-advocacy and ownership of their accommodations, many also desire institutional responsibility, proactive instructor engagement, and a more holistic understanding of accessibility that includes basic needs and emotional well-being. Inconsistencies across courses, administrative gaps, and the pervasive stigma surrounding disability continue to create barriers, particularly in online learning environments. However, the insights offered by participants point to actionable opportunities: fostering open dialogue, adopting “wise practices” rooted in empathy, improving LMS design, and ensuring faculty are equipped and supported to create inclusive learning spaces. Together, these steps can move institutions beyond minimum compliance toward a culture where diverse ways of learning are recognized, valued, and meaningfully supported.

Endnotes

1. Combined due to a small number.References

- Abe, E. S., & Wallace, M. M. (2018). “People see me, but they don’t see me”: An

- intersectional study of college students with physical disabilities. Journal of College Student Development, 59(5), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0052

- Abrams, E. J., Floyd, C. E., & Abes, E. S. (2024). Prioritizing crip futures: Applying crip

- heory to create accessible academic experiences in higher education. Disability Studies Quarterly, 43(4). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v43i4.8270

- Battalova, A., Hurd, L., Hobson, S., Kirby, R. L., Emery, R., & Mortenson, W. B. (2022). “Dirty

- looks”: A critical phenomenology of motorized mobility scooter use. Social Science & Medicine, 297, 1–8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114810

- Benkohila, A., Elhoweris, H., & Efthymiou, E. (2020). Faculty attitudes and knowledge

- regarding inclusion and accommodations of special educational needs and disabilities students: A United Arab Emirates case study. Psycho-Educational Research Reviews, 9(2), 100–111. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1276390.pdf

- Bourne, J., & Winstone, N. (2021). Empowering students’ voices: The use of activity-

- oriented focus groups in higher education research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 44(4), 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2020.1777964

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative

- Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & and Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Brueggemann, B. J., White, L. F., Dunn, P. A., Heifferon, B. A., & Cheu, J. (2001). Becoming

- visible: Lessons in disability. College Composition and Communication, 52(3), 368–398. https://doi.org/10.2307/358624

- Crenshaw, K. (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence

- against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Davis, N. A. (2005). Invisible disability. Ethics, 116(1), 153–213.

- https://doi.org/10.1086/453151

- Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of

- Michigan Press. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/47415

- Doyle, T., Poynton, B., Sukhai, M., & Sinclair, J. (2023). Disability as diversity: Inclusion in

- Canadian higher education. In J. W. Madaus & L L. Dukes III (Eds.), Handbook of higher education and disability (pp. 278–296). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781802204056/book-part-9781802204056-32.xml

- Faure, T., & Sasso, P. A. (2023). Collaborative challenges between educational

- accessibility coordinators and adjunct faculty in supporting autism spectrum students. New York Journal of Student Affairs, 23(1) 1–32. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1401085.pdf

- Gagnon, J. M. (2022). The inaccessible tower: Disability, gender, and contract faculty. In C.

- McGunnigle (Ed.), Disability and the academic job market (pp. 139-161). Vernon Press.

- Garland-Thomson, R. (2006). Ways of staring. Journal of Visual Culture, 5(2), 173–192.

- https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412906066907

- Hills, M., Overend, A., & Hildebrandt, S. (2022). Faculty perspectives on UDL: Exploring

- bridges and barriers for broader adoption in higher education. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotlrcacea.2022.1.13588

- Jacobs, L. (2023). Access to post-secondary education in Canada for students with

- disabilities. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law, 23(1–2), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/13582291231174156

- Kafer, A. (2013). Feminist, queer, crip. Indiana University Press.

- http://muse.jhu.edu/book/23617/

- Kent, M. (2015). Disability and eLearning: Opportunities and barriers. Disability Studies Quarterly, 35(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v35i1.3815

- Kerschbaum, S. L., Eisenman, L. T., & Jones, J. M. (2017). Negotiating disability: disclosure

- and higher education. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9426902

- Kim, W. H., & Lee, J. (2016). The effect of accommodation on academic performance of college students with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 60(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355215605259

- Kroll, T., Barbour, R., & Harris, J. (2007). Using focus groups in disability research.

- Qualitative Health Research, 17(5), 690–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307301488

- Lindsay, S., Cagliostro, E., & Carafa, G. (2018). A systematic review of barriers and

- facilitators of disability disclosure and accommodations for youth in post-secondary education. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 65(5), 526–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2018.1430352

- Lofland, J., Snow, D. A., Anderson, L., & Lofland, L. H. (2006). Analyzing social settings: A

- guide to qualitative observation and analysis (4th ed.). Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

- Meekosha, H., & Shuttleworth, R. (2009). What’s so ‘critical’ about critical disability studies? Australian Journal of Human Rights, 15(1), 47–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/1323238X.2009.11910861

- Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility. (2022). Development of proposed postsecondary

- education standards—Final recommendations report 2022 | ontario.ca. http://www.ontario.ca/page/development-proposed-postsecondary-education-standards-final-recommendations-report-2022

- Newman, L. A., & Madaus, J. W. (2015). Reported accommodations and supports provided to secondary and postsecondary students with disabilities: National perspective. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 38(3), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143413518235

- Pieri, M. (2019). The sound that you do not see. Notes on queer and disabled invisibility.

- Sexuality & Culture, 23(2), 558–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9573-8

- Price, M. (2011). Mad at school: Rhetorics of mental disability and academic life.

- University of Michigan Press.

- Rajan‐Rankin, S. (2018). Invisible bodies and disembodied voices? Identity work, the body

- and embodiment in transnational service work. Gender, Work & Organization, 25(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12198

- Rodgers, J., Thorneycroft, R., Cook, P. S., Humphrys, E., Asquith, N. L., Yaghi, S. A., &

- Foulstone, A. (2023). Ableism in higher education: The negation of crip temporalities within the neoliberal academy. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(6), 1482–1495. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2022.2138277

- Samuels, E. J. (2014). Fantasies of identification: Disability, gender, race. New York

- University Press.

- Samuels, E. (2017). Six ways of looking at crip time. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37(3),

- Article 3. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v37i3.5824

- Shanouda, F., & Spagnuolo, N. (2021). Neoliberal methods of disqualification: A critical examination of disability-related education funding in Canada. Journal of Education Policy, 36(4), 530–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1712741

- Spirtos, M., & Gilligan, R. (2020). ‘In your own head everyone is staring’: The disability

- related identity experiences of young people with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020.1844170

- Titchkosky, T. (2011). The question of access: Disability, space, meaning. University of

- Toronto Press.

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD) |

- Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD). https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd

- Usher, A., & Balfour, J. (2023). The state of postsecondary education in Canada 2023.

- Higher Education Strategy Associates. https://higheredstrategy.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/SPEC-2023_v3.pdf

- Welle, D. L., Fuller, S. S., Mauk, D., & Clatts, M. C. (2006). The invisible body of queer

- youth: Identity and health in the margins of lesbian and trans communities. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 10(1/2), 43–71. https://doi.org/10.1300/J155v10n01_03