Thus, a social model lens advocates re-conceptualizing societal barriers (i.e., environmental and cultural) that marginalize and limit access and opportunities for those with disabilities.

Methods

Design

Narrative approaches and critical discourse analysis undergirded this study. Both methods unveil children’s personal stories and experiences of school life and highlight school inequities. For example, children develop understandings of the self and their worlds through stories (Ahn & Filipenko, 2007; Engel, 2005). Thus, narratives employ stories as a method for exploring personal knowledges and events, and are frequently used to gain insights of marginalized children’s schooling experiences (Barrett, 2009; Chase, 2005; He, Chan, & Phillion, 2008; Hendry, 2007; Patton, 2002). As Chase (2005) explained, narratives may include brief and relevant stories about specific events or people, lengthier stories associated with significant experiences or positions, or life histories or autobiographical stories extending from birth to present day. Throughout this study, narratives allowed a group of minoritized children to provide first-person accounts of provocative and veiled occurrences in their school life, describing specific social experiences within specific contexts.

In this study, the notion of discourse is acknowledged as a social construct, influenced by social relations, histories, and practices. Critical discourse analysis concentrates upon how forms of communication (verbal, written texts, images, etc.) may be utilized to preserve regulated practices of dominant groups (Mills, 2004; Van Dijk, 2004). These regulated practices serve as structures within society and therefore institutions (e.g., schools), sanctioning what is normal, appropriate knowledge, and speech, and as such afford greater power to those following and abiding by these regulated norms. Failing to fit within the dominant regulated practices dictates abnormality and exclusion. Stemming from feminist and post-colonial work, critical discourse analysis aims to challenge dominant discourses, while presenting spaces to access and hear the voices of historically marginalized and silenced groups (Luke, 1997). As such, I explored surfacing discourse within the children’s narratives, investigating how these contribute to forms of school belonging for minoritized children within schools.

Participants

The sample of participants was 6 children (2 girls, 4 boys; ages 10-13) from a non-profit organization for individuals with disabilities in Ontario, Canada. Although some may contend that a sample size of 6 is quite small to draw any kind of research significance, I argue qualitative narrative research is not merely about generalizing results obtained from participants, but rather about valuing voice and varied perspectives that convey others’ experiences of their worlds through their own expressions, with dense details and abounding accounts; this sample size allowed for extensive and more in-depth dialogue and examination of issues related to the children’s schooling experiences. Narrative researchers frequently use smaller sample size groups to strengthen deeper immersion into topics, group cohesiveness, collaboration, and analysis of narratives (Chase, 2005).

All participants were of East Asian ethnic backgrounds (i.e., China and Vietnam) and bilingual in Mandarin and/or Cantonese and English. Four participants were born in Canada, and two emigrated from China to Canada during early childhood (approximately ages 3-5 yrs old). Five participants were diagnosed with ASD along with other disabilities, such as attention deficit disorder, hyperactivity, global developmental delay, cerebral palsy, and speech and language delays. All participants attended segregated special education classes within mainstream public schools, however, 5 participants also received partial integration into “regular” classrooms for certain academic subjects (i.e., gym, mathematics). Participants’ pseudonyms are Gem, Alice, Simon, Mew, Edward, and William.

Data Collection and Analysis

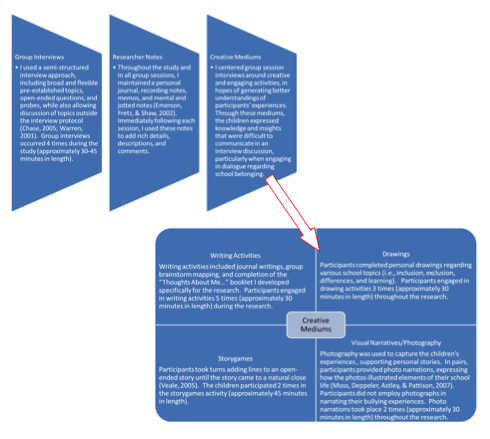

Participants engaged in seven group sessions, approximately 90 minutes/per session, over a four month period. Within the sessions, I collected data through audio taping and various field texts, such as reflective researcher notes, group interviews, and creative mediums – writing activities, drawings, storygames, visual narratives/photography (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mosaic/multi-method research approach to access voices of children with disabilities.

Figure 1 Description. Field texts included: (1) Group Interviews: I used a semi-structured interview approach, including broad and flexible pre-established topics, open-ended questions, and probes, while also allowing discussion of topics outside the interview protocol (Chase, 2005; Warren, 2001). Group interviews occurred 4 times during the study (approximately 30-45 minutes in length). (2) Researcher Notes: Throughout the study and in all group sessions, I maintained a personal journal, recording notes, memos, and mental and jotted notes (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 2002). Immediately following each session, I used these notes to add rich details, descriptions, and comments. (3) Creative Mediums: I centred group session interviews around creative and engaging activities, in hopes of generating better understandings of participants’ experiences. Through these mediums, the children expressed knowledge and insights that were difficult to communicate in an interview discussion, particularly when engaging in dialogue regarding school belonging. Creative mediums employed were (3a) Writing Activities: Writing activities included journal writings, group brainstorm mapping, and completion of the “Thoughts About Me…” booklet I developed specifically for the research. Participants engaged in writing activities 5 times (approximately 30 minutes in length) during the research. (3b) Drawings: Participants completed personal drawings regarding various school topics (i.e., inclusion, exclusion, differences, and learning). Participants engaged in drawing activities 3 times (approximately 30 minutes in length) throughout the research. (3c) Storygames: Participants took turns adding lines to an open-ended story until the story came to a natural close (Veale, 2005). The children participated 2 times in the storygames activity (approximately 45 minutes in length). (3d) Visual Narratives/Photography: Photography was used to capture the children’s experiences, supporting personal stories. In pairs, participants provided photo narrations, expressing how the photos illustrated elements of their school life (Moss, Deppeler, Astley, & Pattison, 2007). Participants did not employ photographs in narrating their bullying experiences. Photo narrations took place 2 times (approximately 30 minutes in length) throughout the research.

In using a multi-method approach to accessing children’s understandings of inclusion, marginalization, and diversity, I obtained a more thorough and clearer understanding of participants’ views on these topics, and it supported participants’ various forms of communication and expression (e.g., some participants preferred journal writing about certain issues, rather than talking about them during interviews). Using such a “mosaic” research approach accessed the children’s multiple views and offered creative participatory techniques (Clark & Moss, 2001). Furthermore, ensuring creative mediums served as research data, I requested that participants verbally explain creative submissions. I also tailored these methods to suit participants’ abilities and developmental level (e.g., providing more visual supports, Picture Exchange Communication Symbols, etc). Regular break periods were held during each session. I also developed a group session itinerary and script guiding facilitation of each session, however, I maintained flexibility within each session, adapting the schedule if necessary to accommodate for the group climate.

To analyze the data, I employed both narrative and critical discourse analysis approaches. Using a narrative approach I made sense of the children’s stories and experiences by identifying emerging elements, highlighting contexts, characters, key events, and conclusions (Creswell, 2005). I analyzed the data in search for patterns and tensions, categorizing the texts, considering language use (e.g., metaphors), and participants’ body language and emotions. This was carried out whilst acknowledging participants’ understandings derive from varying beliefs and values, and accounts of past experiences are embedded within personal cultural, historical, political, and linguistic frameworks (Fox, 2009). Together, as narrative methods underscores, the children and I negotiated between the data, collaboratively telling, re-telling, writing, and re-writing their narratives. Thus, I re-presented to participants multiple versions of their narratives throughout the research, providing opportunities to debate which stories and images to include, verify data interpretations and intended meanings, and ensure narratives were conveyed as they desired.

I then utilized critical discourse analysis to further examine participants’ completed narratives. Based upon the study’s focus on schooling experiences of minoritized groups, general theories and methodologies guiding critical discourse analysis included sociocognitive and discourse-historical approaches (McGregor, 2003; Wodak & Meyer, 2009).

Findings and Discussions

As participants explored notions of school belonging and exclusion, bullying experiences and victimizations emerged from their narratives. This finding demonstrates the escalated prevalence of such school-based encounters during the middle years, particularly among children with disabilities, and more specifically among children with ASD.

Characteristics of Bullies

The children expressed general understandings and characteristics of bullies: (a) they come in a variety of ages and sizes, (b) students mostly from the regular classroom, however can also derive from the special education class, (c) in Grades 5-8, (d) portray negative attitudes, and (e) students mostly with light brown or white skin tones. For instance, as participants engaged in a storygame regarding a Tamil girl with autism, they highlighted her experiences of victimization and described her bullies, “The students telling her this [name calling] are in Grade 7 and Grade 8. These students have light brown skin and they were also white.” Edward similarly acknowledged, “Bullies like to be bad….It's mostly the 8th graders that bully, because they are teenagers,” yet Simon and William asserted bullies do not always emerge as older teens. William contended, “All the bullies are from Grade 5,” and Simon explained his multiple encounters with older and younger bullies:

He [the bully] is in Grade 8. He is in the special needs class….[Also the] Grade 6 boys.... Two of the boys were from the regular class and 1 boy is autistic and he is in the special education class….[But] mostly it's the regular students that say negative stuff….I don't think only teenagers bully, because these bullies are in Grade 6 and they're not 13 yet. This bully was small and younger.

Interestingly, despite bullying incidents rising in middle school years, Berger (2007) reported a United Nations survey, Young People’s Health in Context, found as children (ages 11-15) grew older, progressing through middle and early high school years, the number of bullies increased yet victimization decreased. One plausible reason may be that older bullies select younger victims. Cappadocia et al. (2012) indicated younger children with ASD are also more likely to become victims of bullying, as reported by parents of children with ASD. However, the authors noted this age-related factor may be due to parents’ unawareness of bullying incidents in their older children’s lives (e.g., the older child may not report bullying experiences to parents, specifically as they begin developing greater levels of self-reliance).

Although some children from the study described older bullies from upper middle school (i.e., Grade 8), others explained experiences of victimization by younger bullies in lower middle school (i.e., Grades 5-6); thus, contradicting some of the existing research. Simon and William reported experiences of victimization as older students (i.e., Grades 7-8) being bullied by younger students (i.e., Grades 5-6). Moreover, William, one of the oldest participants in the research group clearly stated that bullies derive from the 5th grade, which was the lowest grade level highlighted by participants.

As Edward and Simon shared their understandings of bullies, they associated bullies with behaving troublesomely and verbalizing negative statements/comments toward students. Cook et al. (2010) reported this aura of bullies acting waywardly and maintaining a negative disposition is one characteristic of the typical bully (i.e., “negative attitudes and beliefs about others” [p. 75]). Participants conveyed strong disapproving feelings toward these typical bullies, and justifiably so, as some participants endured and/or observed frequent bullying experiences throughout their school life. For example, participants reported, “It makes me feel angry and upset. I don't think it's fair, because they are bullies” (Edward), “I think bullies are negative” (Simon), and “Bullies are the WORSE!” (William). Likewise, Norwich and Kelly (2004) demonstrated that 83% of their 101 participants with moderate learning disabilities also recounted some form of victimization, in which 77% of this group capably described their feelings regarding bullies. Similar to Edward, Simon, and William, 56% of Norwich and Kelly’s (2004) participants emphasized negative emotions regarding bullying (e.g., hurt, upset, etc…).

Physical, Verbal, and Social/Relational Aggression

A majority of participants described personal bullying experiences involving “direct” attacks from a bully (i.e., both bully and victim are present during the bullying encounter) (Berger, 2007, p. 95). Evidence suggests children with disabilities experience increased amounts of various forms of victimization compared to their peers without disabilities, including verbal aggression, social exclusion/relational bullying, and physical aggression (Berger, 2007; Rose et al., 2011). Although physical bullying and aggression tend to decrease as children mature (Berger, 2007), studies still report small amounts of physical aggression among middle years children with disabilities (e.g., Norwich & Kelly, 2004). This was also the case for my participants, as they described enduring physical bullying experiences of pushing, spitting, punching, and kicking. Alice explained her confusion and desire to remain composed after being pushed by her locker:

Once, someone pushed me by the locker. I don't know why they pushed me, but I did not cry. I didn't do anything afterwards, except I told the teacher. I don't know what the teacher did to that student who pushed me.

Simon also indicated incidents of pushing and spitting: “Sometimes they [bullies] push me....These boys also try to spit at me.” He further explained:

One time, one of the Grade 6 boys in the regular class ran so fast and pushed me while I was near my locker. It was just before morning recess…that guy, he pushed me purposely. I got hurt. I didn't bully him back. Once that boy pushed me, I told the teacher and the teacher had a conversation with him. He was sent to the principal's office after the conversation. Once he got sent to the principal's office, the regular boy, he will never do that again. He is a bully. It makes me a little bit upset, sad, and mad too. I was not happy with what happened. I wished I did not get hurt.

Simon acknowledged the deliberate attempt for the bully to catch him “off-guard” and cause harm. William also vividly described his experiences and conceptualizations of physical bullying at school:

Bullying is also when someone kicks you.... After someone sticks up their middle finger they will punch you…if they stick up the middle finger, you'll be punched in the face..... Once, I saw Kwai with Rocky at recess, and Kwai punched people in the face, like "pew, pew, pew, pew!" Then, he was sticking up his two middle fingers. Sometimes there is bullying in our lunch room. Like last time at lunch time on Tuesday, Shakira and Devin were having a big fight. They got into a big fight and they were pushing each other, like "pew, pew!" And the lunch lady said, "You're in big trouble! You're going to speak to the teacher!" Devin kept pushing Shakira, and she was like "Oh I want to stop you!" They didn't stop fighting, and finally the two lunch ladies came over and stopped it. This is a mean situation, just the same thing as if you show your middle finger.

From his accounts, William often observes physical aggression at school, and he clearly associates physical aggression with verbal aggression, merging the two forms of bullying into one entity.

Participants’ discussions of physical encounters were reported less frequently and descriptively compared to their reports of verbal aggression. Sweeting and West (2001) suggested some students and teachers stereotypically relate only physical aggression to notions of bullying, often disregarding other forms, such as verbal aggression, and social exclusion. Research highlights educators in particular perceive physical aggression and threats as a more serious concern compared to social and verbal aggression (Rose et al., 2011). Yet, as children mature (e.g., during the middle years) instances of verbal and relational bullying occur more regularly compared to physical bullying, becoming the customary approach for bullies, including among children and youth with ASD, learning disabilities, and verbal/speech communication delays (Berger, 2007; Cappadocia et al., 2012, Crouch, 2010; Norwich & Kelly, 2004; Wickenden, 2011). Moreover, children with disabilities report experiencing forms of social and verbal aggression much more frequently than forms of physical bullying (Rose et al.). Participants’ assertion of prevalent social/relational and verbal aggressive experiences is consistent with the research, reporting incidents of staring, teasing, humiliation, swearing/profanity, inappropriate language, and ostracization.

Wickenden (2011) illustrated the ogling that youth with physical and communicative differences often tolerate from curious observers. Similarly, participants described moments of being stared at by other students, inducing a sense of exclusion, fear, and timidity:

“I think it's negative when people stare at you at school.” (Gem)

“I often feel scared [at school] because people keep looking at me…I don't know why.” (Mew)

“Sometimes I feel shy when I think someone is annoyed and looking at me.” (Edward)

Staring also appeared to be interconnected with other forms of verbal bullying and social exclusion, such as swearing, teasing, and ostracization:

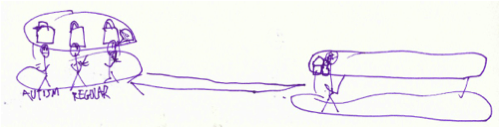

Another time, a group of Grade 6 boys started to bully me in the cafeteria. Two of the boys were from the regular class and 1 boy is autistic and he is in the special education class. They were staring at me for 15 minutes when I was eating lunch. This one is not good. That was negative. I don't know why they were staring at me, but they were staring at me, looking at me for 15 minutes in a row. Also, one day they were eating lunch and they open their mouth and look at me. That makes me feel excluded. I had to sit somewhere else. Once I sit on the other side, they do not look at me anymore. When the teacher looks at those Grade 6 boys they were not staring at me anymore, but when the teacher is not looking at them, they are starting to stare at me. I did not tell the teacher or the lunch helper, but my friends already knew and they helped me. They're all making fun of me, all of them. They sometimes…the two regular boys from the regular class they swear at me, but the autistic boy does not swear. I heard them say the "F" word and I saw them stick up the middle finger. Two of them are sticking up the finger. They were standing and called me the "F" word. I felt very sad, but I did not cry.

Image 1: This is me sitting at the lunch table in the cafeteria. These are the 3 Grade 6 boys. Those 2 guys in the regular class say the "F" word to me. They make fun of me and say the other swear words too. The other guy is the autistic guy. (Simon)

Image 1 Description. Simon conveys his bullying experience in the cafeteria through a drawing. To the left of the page he draws three boys sitting together at a lunch table. They each have lunch boxes in front of them on the table. Simon identifies one boy as a student with autism in his special needs classroom; he writes the word “autism” underneath the boy. The other 2 boys are from the regular classroom; he writes the word “regular” underneath the boys. Simon draws the 2 boys from the regular classroom sticking their middle finger up toward him. To the right of the page Simon draws himself sitting alone at a separate table with his lunch box. He draws an arrow from his table across the page to the table with the three boys.

Simon candidly reported feelings of school exclusion and social bullying from other peers during his lunch periods. Despite his distressed emotions from the ostracization and teasing, he remained composed, perhaps for fear of inciting more teasing and bullying.

The use of profanity and inappropriate language emerged as a segment in participants’ bullying experiences, representing its own form of social bullying. William considered his experiences with verbally aggressive and offensive school bullies:

Kwai makes me feel excluded too. I am annoyed from him. He bullies me and other classmates! He calls people names and swears in school. He says the “F” word…“F-U-C-K.” He also sticks up the middle finger. Kwai makes me feel badly. Elton also makes me feel excluded. He says inappropriate stuff in Chinese. One time I heard him say “Victoria drinks coffee blood.”

Simon also reported another experience of verbal aggression and social exclusion from a student in his special education community class:

There was an autistic kid. He is in Grade 8. He is in the special needs class. He swears at me. I go to that boy to see something, because he was on the computer. He said "Go away" and he swore at me. That made me feel excluded..... This is a picture of the Grade 8 boy being negative. He is at the computer.... Man, that guy makes me feel excluded. This makes me feel excluded.

Image 2 Description. Simon conveys his bullying experience with the Grade 8 boy with autism through a drawing. To the right of the page, Simon draws the boy with autism sitting in front of the computer. The boy is turned around, facing behind, and looking at Simon. Simon draws himself to the left side of the page, with both arms up in the air, and his face turned away from the boy; he draws a frown on his face.

A few participants also described humiliating and embarrassing experiences surrounding specific topics, such as a lack of finances and showing of “private parts.” Edward expressed, “Sometimes people make fun of you and laugh at you. For example, if a student has a broken shoe, bullies might laugh at them.” Edward draws a connection between bullying and students who may not be able to afford new material items. Highlighting the awkwardness of when other students comment on genitalia, William explained, “It's not nice…it's like all the people [bullies] talk about penises…that's a private part.” Furthermore, Edward described pulling students’ pants down as a mortifying form of social bullying, “An example of bullying is when someone pulls your pants down and other kids laugh at you. It's not funny and it's humiliating, but it has not happened to me.”

Strategies to Manage Bullying Encounters

Noticeably, from their descriptions of bullying experiences, participants’ highlighted strategies to manage bullying behaviour. Predominant strategies included, reporting the situation to school authority (i.e., teacher and/or principal) and ignoring the bullying behaviour:

“I think when others bully you, you should tell the principal or ignore it.” (Edward)

“If you are bullied you should tell the teacher.” (William)

“Once, someone pushed me by the locker….I didn't do anything afterwards, except I told the teacher. I don't know what the teacher did to that student who pushed me.” (Alice)

Simon in particular employed a variety of these approaches to deal with his recurrent bullying encounters:

“I went away and I ignored it [the bullying behaviour]….I turned and walked away [from the bully].” ;

“I had to sit somewhere else. Once I sit on the other side, they do not look at me anymore.” ;

“I try to ignore the bullying and I sometimes tell the teacher.” ;

“I didn't bully him back….I don't bully them back, but they think I do.”

Participants’ tactics for managing school-based victimization incidents are consistent with some of the research examining children’s bullying experiences (e.g., Norwich & Kelly, 2004), as well as with adult advice regarding dealing with bullies (Berger, 2007; Ontario Ministry of Education [OME], 2011). Evidently, participants’ responses strongly paralleled the Ontario educational discourse on methods to handle bullying experiences. For example, the OME (2011) developed a bullying guide for parents, in which it advocates, regardless of a child’s age, if s/he is experiencing forms of bullying parents should encourage their child to “walk away,” “don’t hit back,” “tell an adult,” “talk about it,” “find a friend,” and “call kids help phone” (p. 3). Participants reported carrying out four of the six advised suggestions (i.e., walk away, don’t hit back, tell an adult, and find a friend). Although appearing as logical and rational methods for children to employ, these strategies occasionally backfire for victims. From children’s perspectives, reporting the incident to a trusted school adult is an unfavourable tactic for a variety of reasons (Berger, 2007; Ferráns et al., 2012): (a) adults may mismanage the situation, (b) adults make no difference to the situation, (c) adults do not understand the child’s perspectives and feelings, (d) children fear causing trouble for others, and (e) adults sometimes exacerbate the situation. When experiencing bullying, children much prefer seeking support from a friend, rather than school authority. This was demonstrated by Simon, as he explained in one bullying scenario, “I did not tell the teacher or the lunch helper, but my friends already knew and they helped me.” The presence of peers serves as a protective factor during bullying (e.g., defend and assist victim), as well as reduce the risk of victimization, especially among children with ASD (Asher & Gazelle, 1999; Cappadocia et al., 2012). However, considering the social and communicative complexities children with ASD face, including challenges in developing and sustaining peer relationships, they may rarely experience the value of supportive friendships serving as protective factors. Therefore, as participants may not possess steady and established peer groups, they consequently turn to support from school authority, which may not be the best choice.

Mew, on the other hand, denied following suggested procedures for dealing with bullies, and instead seeks physical vengeance. He explained:

I have never been bullied. If someone swears at me at school I would probably use violence against them. I would punch him or break his neck off. I think I bully other kids, because other students bully me, so I bully them back. I would kick their butt off.

Plainly, Mew’s response exhibits his desire for physical revenge against bullies; however, he also contradictorily expressed on one hand never experiencing bullying, yet on the other hand bullying other children as a form of retaliation. Throughout his narrative, Mew reported a sense of fear and embarrassment in school due to others staring at him, highlighting a form of relational aggression. Possibly Mew is ashamed to report experiences of social bullying. Mew’s type of victimization aligns with the bully/proactive victimology, in which some victims develop bullying traits and attack others due to their victimization (Berger, 2007; Cook et al., 2010; Rose et al., 2011). As participants grappled with suitable methods to manage encounters with bullies, I inquired whether they would change or do anything differently during their moments of victimization. William realistically explained, “I would not change anything on those days with the bullies, because it just be sticking [sic], just the same.” His reaction that the bullying situations remain unaltered, regardless if victims manage these experiences differently may reflect some students with disabilities’ understandings that bullying experiences are unpreventable, inevitable, and usual occurrences, dismally out of victims’ control.

Difference and Victimization

Minoritized students carry with them markers of difference, contradicting conceptualizations of the normal student. Participants capably conveyed understandings of difference and its correlation to marginalization as a result of deviating from mainstream school norms. Participants also described instances of bullying and marginalization due to differences. This predominantly emerged as they engaged in storygames during the research sessions. For instance, in developing a story regarding a girl experiencing teasing at school, participants highlighted repeated incidents of verbal aggression:

There once was a girl who was teased and made fun of all the time at school.

She got bullied all the time.

They make fun of her and they say "Your name is stupid."

She always trips all the time and they call her names, like "clumsy."

She cried.

It was cruel.

They called her stupid and all she wanted to do was play UNO with her friends.

She was in the special class.

When narrating a story of a non-ambulant boy with vision impairments, participants explained, “The boy was distracted by bullies.....He came to school scared, and he came out of school scared. He feels scared, scared, at school.” Participants also described a story highlighting bullying of a girl with intersecting differences:

Once there was this girl with short hair and brown skin.

She spoke languages like Tamil and she had autism.

She had glasses.

She was bored and tired at school.

She always felt sad when she went to school, because she got teased all the time.

People at school call her funny names, like "Bad Bird."

They also call her bad names…bad name calling.

They make fun of her voice and the way she talks.

Some people did not make fun of her autism, but other people did.

They made fun of her, because she had autism and they say "Hey, what are you? Your name is stupid."

They call her stupid, because she has autism.

Some people did not make fun of her language, but other people did.

They bullied her.

Some people did not make fun of her skin colour, but sometimes people did.

They called her "You are black."

That made her feel sad.

She cried.

They made fun of the girl and thought she had a rash.

They thought her black skin had a rash, and they made fun of her.

They think it's bleeding blood, and it's not good.

They made fun of her skin colour, because it's different.

They thought it was bad and worse.

They called her skin "Horrible."

The students telling her this are in Grade 7 and Grade 8.

These students have light brown skin and they were also white.

Participants’ stories emphasized characters’ emotions of fear, sadness, and upset, supporting reported feelings by some participants who experienced bullying in school. For example, both Simon and Mew expressed encountering some form of physical, verbal, and/or relational aggression, and they both maintained a sense of fear and desolation when thinking about school. In describing bullying experiences among minoritized children, participants’ stories also explored issues related to victimization, such as disability, attending special education classrooms, language, race, ethnicity, and physical appearance.

Participants clearly associated bullying with differences. They demonstrated a strong awareness of the victimization and perpetration minoritized students may face due to personal differences. For instance, when narrating stories of the two girls with disabilities, participants related victimization to physical ability (i.e., clumsy, always tired at school) and lower intelligence (“Your name is stupid,” “They call her stupid”). However, victimization significantly escalated once the protagonist took on intersecting differences. An illustration of this is noted in participants’ story of a Tamil girl with autism. In addition to victimization due to her physical ability and intelligence, she incurred further bullying resulting from physical appearance (i.e., glasses), communication difficulties (i.e., they make fun of her voice and the way she talks), abnormality of her autism diagnosis (i.e., bullies saying “Hey what are you?”), language, and skin colour (i.e., called her skin black, skin had a rash, bleeding skin, skin colour was “bad,” “worse,” “horrible”). Participants’ raised two issues in their associations with darker skin colours: (a) negative stereotypes (e.g., dirty, rash), and (b) disapproving and negative nature of possessing darker skin (e.g., black skin colour was used as an insult toward the Tamil girl, horrible, worse, bad). Interestingly her bullies maintained lighter skin tones (i.e., light brown and white). Participants’ clearly conceived superiority to white skin colour. They also recognized the complexities and challenges endured by children with disabilities, and the potential for amplified victimization and bullying in schools for those with multiple intersecting differences.

Intriguingly, however, when participants were asked whether they consider themselves vulnerable to bullying due to their differences, a few participants disagreed. Edward asserted, “I think children get bullied if they are undifferent [sic] or different….I don't think I get bullied, because I'm different or because I have autism.” Similarly, William indicated, “I don't think I would get bullied because of I have autism.” Both participants did not consider their personal differences, such as autism, to promote bullying encounters. However, Simon acknowledged rumours of bullying resulting from differences, yet appeared uncertain whether his victimization stems from personal differences:

I have heard that somebody got bullied, because they are different. I don't think they bully me, because I'm in a different class…the special class. I don't know…I don't know. I don't think they know if I'm in the special or regular class, but they continue making fun of me.

Conclusions

Evidently, from this study, schools remain as unsafe and imbalanced sites distributing greater social agency among non-minoritized students who better align within dominant norms and ideals. Differences often incite feelings of discomfort, fear, shame, and marginalization resulting from deviation of societal majority norms. Along this continuum of normalcy defined by dominant groups, negative attitudes and stereotypes surface the more an individual differs. Seemingly, minoritized children with intersecting differences incur consequences, such as increasing their odds of physical and/or social victimization. Consequently, this reinforces stereotypes that some minoritized children, especially those with disabilities, may become victimised in some way during their school life. The concern, herein, surrounds blaming children for oppression, stigmatization, and marginalization due to differences, rather than addressing the negative social construction surrounding those who are different. These social constructions affix differences to deficits and deficiencies, fuelling the “…need to stand apart from those who are ‘different’…” (Asher & Gazelle, 1999, p. 19).

Although adults and school authority may serve as safeguards for minoritized students experiencing victimization, it appears that as children seek greater autonomy during middle to early high school years, adults further aggravate bullying situations. Friends appear to be the primary choice among victims in alleviating bullying encounters. With the camaraderie and solidarity characteristic of many school friendships, fellow peers may defend victims, steer victims out of bullying situations, and/or console victims after bullying incidents. Thus, friendships function as a protective element during bullying. Yet, many children with ASD and other developmental disabilities struggle with establishing friendships. Perhaps then, in managing school bullying the adult role is better suited to one that is proactive, rather than reactive (i.e., providing protection after victimization) to the situation. That is, proactively supporting minoritized children in developing healthy interpersonal relationships with other students. Although fairly arduous for children with ASD and other developmental disabilities, establishing peer groups and relationships within inclusive environments may be critical for reducing victimization and increasing a positive sense of school belonging. This may entail re-arranging school surroundings to foster a culture of school inclusion among all students and expanding educators’ and students’ thinking about notions of normalcy and differences. Namely, identifying what constitute norms among student bodies, and reflecting upon how to challenge these pejorative societal standards to include minoritized students who extend beyond social, cultural, and ability normalcy classifications.

Schools are normalizing sites whereby formal and hidden curricula and dominant groups’ ideologies and standards dictate particular norms, engendering valuable citizens (Holt, Lea, & Bowlby, 2012). Shifting toward majority groups’ ideals, norms, and values contributes to the power pool of dominant groups, “…[the] spread of power – away from banishment of the minority towards regulation of the majority” (Holt et al., 2012, p. 2194); thus, normalization enacts power. However, what is normal can not exist without the abnormal. Societal and educational institutions immerse children within an abnormalization process, specifically those from traditionally marginalized groups (i.e., racially, ethnically, linguistically, and ability related groups), categorizing, labelling, separating, and conveying images of the abnormal Other (Holt et al.; Liasidou, 2012). This image of the “Other” among children with disabilities manifests itself more and more among children who are also from racially, ethnically, and economically diverse backgrounds in comparison to dominant White upper class groups (Reid & Knight, 2006). Therefore, recognizing intersections of differences among minoritized children is imperative, but even more so is “understanding the intersections of systems of oppression and challenging the multiplicity of factors that disable certain groups of students…” (Liasidou, p. 170).

This research sheds light onto understandings of bullying and victimization from a group of Canadian children with intersecting differences of race, ethnicity, language, and disability. The study powerfully highlights the voices of children with disabilities, as they are generally excluded from educational research, and most chiefly research concerning their lives in relation to difference and inclusion. It is one of the few studies vividly portraying bullying experiences from the voices of children with disabilities, particularly autism, who also have various intersecting differences. This study engaged children with autism and other disabilities in agency-driven qualitative research methods to access their voices. Employing inclusive and creative child-centred approaches via multi-methods, participants openly engaged in meaningful conversations related to school belonging and bullying experiences. With power in the research process and trust in the research environment, minoritized children candidly shared experiences of victimization during schooling.

Although this study gathered rich accounts from a small group of children with disabilities, it raises awareness for the need of conducting larger studies whereby students with disabilities serve as co-researchers and participants. Frequently, voices of parents, educators, and paraprofessionals are included in research about children with disabilities, sharing concerns, challenges, hopes and dreams, often communicating on behalf of the children. Yet, young people with disabilities have the right to actively participate in research regarding their lives, and researchers have the responsibility to provide suitable spaces and opportunities of engaging, accessing, and listening to the voices of these children. Future research may also address bullying issues and the importance of systemic change within educational institutions, investigating ways to confront traditional conceptualizations of normalcy and difference to include all children within safe school spaces.

Acknowledgements

I extend great gratitude to my participants, Gem, Alice, Simon, Mew, Edward, and William, for their forthright sincerity and trust in sharing personal schooling experiences. I also thank the centre and participants’ families for their cooperation. This research project received support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) (2012-2013).

References

Ahn, J., & Filipenko, M. (2007). Narrative, imaginary play, art, and self: Intersecting worlds. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34(4), 279-289.

Asher, S. R., & Gazelle, H. (1999). Loneliness, peer relations, and language disorder in childhood. Topics in Language Disorders, 19(2), 16-33.

Barnes, C. (2012). Understanding the social model of disability: Past, present and future. In N. Watson, A. Roulstone, & C. Thomas (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies (pp. 12-29). London: Routledge.

Barrett, A.M. (2009). African teacher narratives in comparative research. In S. Trahar (Ed.), Narrative research on learning: Comparative and international perspectives (pp. 109-128). Oxford: UK, Symposium Books.

Berger, K.S. (2007). Update on bullying at school: Science forgotten? Developmental Review, 27, 90-126.

Burbules, N.C. (1997). A grammar of difference: Some ways of rethinking difference and diversity as educational topics. Australian Education Research, 24(1), 97-116.

Cappadocia, C. M., Weiss, J. A., & Pepler, D. (2012). Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(2), 266-277.

Chase, S.E. (2005). Narrative inquiry: Multiple lenses, approaches, voices. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.) (pp. 651-679). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Clark, A., & Moss, P. (2001). Listening to young children: The mosaic approach. London: National Children’s Bureau and Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25(2), 65-83.

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research. Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall.

Crouch, R. D. (2010). “They got a spot for us in this school”: Sense of community among students of colour with disabilities in urban schools. Retrieved from Via Sapientiae: The Institutional Repository at DePaul University, Theses and Dissertations. http://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/65 (Paper 65).

Emerson, R.M., Fretz, R.I., & Shaw, L.L. (2002). Participant observation and fieldnotes. In P. Atkinson, A. Coffey, S. Delamont, J. Lofland, & L. Lofland (Eds.), Handbook of ethnography (pp. 353-368). California: Sage Publications.

Engel, S. (2005). Narrative analysis of children’s experience. In S. Green & D. Hogan (Eds.), Researching children’s experience: Approaches and methods (pp. 199-216). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Ferráns, S.D., Selman, R.L., & Feigenberg L.F. (2012). Rules of the culture and personal needs: Witnesses’ decision-making processes to deal with situations of bullying in middle school. Harvard Educational Review, 82(4), 445-469.

Fox, C. (2009). Stories within stories: Dissolving the boundaries in narrative research and analysis. In S. Trahar (Ed.), Narrative research on learning: Comparative and international perspectives (pp. 47-60). Oxford: UK, Symposium Books.

Gabel, S.L., & Connor, D.J. (2008). Theorizing disability: Implications and applications for social justice in education. In W. Ayres, T. Quinn, & D. Stovall (Eds.), The handbook for social justice in education (pp. 377-399). New York: Routledge.

Greene, S., & Hill, M. (2005). Researching children’s experience: Methods and methodological issues. In S. Green & D. Hogan (Eds.), Researching children’s experience: Approaches and methods (pp. 1-21). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

He, M.F., Chan, E., & Phillion, J. (2008). Language, culture, identity, and power: Immigrant students’ experience of schooling. In T. Huber-Warring (Ed.), Growing a soul for social change: Building the knowledge base for social justice (pp. 119-144). Charlotte, NC: IAP-Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Hendry, P.M. (2007). The future of narrative. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(4), 487-498.

Holt, L., Lea, J., & Bowlby, S. (2012). Special units for young people on the autistic spectrum in mainstream schools: Sites of normalisation, abnormalisation, inclusion, and exclusion. Environment and Planning A, 44, 2191-2206.

Kanani, N. (2011). Race and madness: Locating the experiences of racialized people with psychiatric histories in Canada and the United States. Critical Disability Discourse, 3, 1-14.

Kincheloe, J.L. (2008). Critical pedagogy (2nd ed.). New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc.

Liasidou, A. (2012). Inclusive education and critical pedagogy at the intersections of disability, race, gender, and class. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 10(1), 168-184.

Luke, A. (1997). Theory and practice in critical discourse analysis. In L. Saha (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the sociology of education (pp. 50-56). Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science Ltd.

McGregor, S.L.T. (2003). Critical discourse analysis: A primer. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 15(1), 1-11.

Mills, S. (2004). Discursive structures. In Discourse (2nd ed.) (pp. 43-68). New York: Routledge.

Moss, J., Deppeler, J., Astley, L., & Pattison, K. (2007). Student researchers in the middle: Using visual images to make sense of inclusive education. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 7(1), 46-54.

Norwich, B., & Kelly, N. (2004). Pupils’ views on inclusion: Moderate learning difficulties and bullying in mainstream and special schools. British Educational Research Journal, 30(1), 43-65.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2011). Bullying. We can help stop it: A guide for parents of elementary and secondary school students. ON: Queen’s Printer. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/parents/bullying.pdf

Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Petrou, A., Angelides, P., & Leigh, J. (2009). Beyond the difference: From the margins to inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(5), 439-448.

Rauscher, L., & McClintock, J. (1996). Ableism curriculum design. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffen (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (pp. 198-231). New York: Routledge.

Reid, D. K., & Knight, M. G. (2006). Disability justifies exclusion of minority students: A critical history grounded in disability studies. Educational Researcher, 35(6), 18-23.

Rose, C.A., Monda-Amaya, L.E., & Espelage, D.L. (2011). Bullying perpetration and victimization in special education: A review of the literature. Remedial and Special Education, 32(2), 114-130.

Sweeting, H., & West, P. (2001). Being different: Correlates of the experience of teasing and bullying at age 11. Research Papers in Education, 16(3), 225-246.

Van Dijk, T.A. (2004). Critical discourse analysis. In D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen, & H. Hamilton (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 352-371). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Veale, A. (2005). Creative methodologies in participatory research with children. In S. Green & D. Hogan (Eds.), Researching children’s experience: Approaches and methods (pp. 253-272). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Warren, C.A.B. (2001). Qualitative interviewing. In J.F. Gubrium & J.A. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research: Context and method (pp. 83-101). California: Sage Publications.

Wendell, S. (1996). The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability. New York: Routledge.

Wickenden, M. (2011). “Talk to me as a teenager”: Experiences of friendship for disabled teenagers who have little or no speech. Childhoods Today, 5(1), 1-35.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2009). Critical discourse analysis: History, agenda, theory, and methodology. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (2nd ed.) (pp. 1-33). London: Sage Publications Ltd.

1 In this study, the term minoritized children refers to those with intersecting differences of race, ethnicity, language, and disability. The term emphasizes enactments of power imbalances between children who fit within majority societal and schools norms and those who do not.