More than Sport: Representations of Ability and Gender by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) of the 2004 Summer Paralympic Games

Nancy Quinn BScPT, MSc

University Affiliation: University of Toronto

nancy[dot]quinnrehab[at]gmail[dot]com

Karen Yoshida BScPT, MSc, PhD

Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science Institute

University of Toronto

Abstract

Purpose

To examine the CBC’s television coverage of two highlighted Canadian Paralympic athletes who participated at the 2004 Summer Paralympic Games held in Athens, Greece. This analysis focuses on representations of ability and gender to consider the repercussions of these representations for Paralympians, people living with physical difference, and spectators.

Methods

Informed by disability studies theory and Garland-Thomson’s (2000) work, qualitative research methods were used to analyze segments of CBC’s television coverage of two Canadian Paralympians, one male and one female, for dominant and recurring themes.

Results

Multiple positive representations of athletes were presented in the data. The dominant theme was the athletic. Though a positive alternative to negative stereotypes of ability this representation is used solely for the female athlete in this case study. The analysis of the male athlete revealed a more nuanced, complex representation. Within this analysis, the asexuality of female athletes with a physical difference is perpetuated and male hegemony within sport is reinforced.

Conclusions

Media has a powerful role in the construction of social perceptions of people with physical difference. Based on this analysis, the CBC coverage promoted a more fully human portrayal of the highlighted male Paralympian. However, its representation of the female athlete continued to reinforce ableist assumptions regarding ability and the asexuality of women with a disability. Sport journalism is a powerful medium that constructs representations of people with physical difference. However, critical analyses of these representations are necessary to reinforce those that are positive and realistic representations of people with physical difference.

Keywords

- Ability/disability

- Sport

- Media

- Representation

- Gender

- Canada

Introduction

Historically the media, including Canadian media, has constructed a culturally negative identity for people living with physical difference (Drake, 1994). According to Zola (1985), the expression of disability by the media has profound effects on society’s impressions and prejudices towards persons with physical difference. Both Longmore (1987) and Garland-Thomson (2000) have shown how media has represented disability through lenses or rhetorics of pity, wonder, exotica, and realism.

Considered within the broader context of daily life, the lived reality of many of Canada’s reported 3.8 million Canadians living with disability is socially, politically, and economically disadvantaged (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2012). As indicated in Canada’s 2010 Federal Disability Report, people with disabilities are over-represented within the low-income population. They are more likely to live alone and to not have graduated from high school than people without disabilities. The effects of disability on work (e.g., occupation, hours of work, and earnings) help explain why low income is more common among people with disability.

Medical discourse is the dominant discourse related to physical difference and often presents disability as physical incapacity. This understanding of disability reinforces a cultural preference for able-bodiedness (Titchkosky, 2009). For Canadians with physical difference, such preference generates discrimination and exclusion in daily life (Silva & Howe, 2012).

The Paralympic Games is the second largest multi-sport games in the world, second to the Olympic Games. Paralympians are elite athletes with physical difference who compete in a variety of sporting disciplines or parasport. In 2004, Canada sent a team of 150 athletes to Athens to compete in the XII Summer Paralympic Games. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) provided 21 hours of television coverage of the Games to spectators in Canada. While this number of hours of coverage is limited relative to the broadcast hours of the 2004 Olympic Games, at that time it was the greatest number of hours ever provided by the CBC for Paralympic coverage.

In this paper, the researchers examine the analysis of the CBC’s representation of ability during these Games with a specific focus on two successful Canadian Paralympians, one female and one male. It is acknowledged that the study’s focus on successful Paralympic athletes may divert attention from the marginalized social conditions of many Canadians with physical difference. Because the analysis revealed alternative media representations of disability that may support a more realistic understanding of Canadians with physical difference, there may also be positive implications for those who live with physical difference and are not athletes, as well as the broader social community. When Canadians with physical difference are represented as athletes, scholars, parents, and lovers – as fully human – this troubles the normative boundaries of humanness and creates space for broader notions of inclusion.

The research presented in this paper is grounded in the social model of disability. In this model, disability is a social construction rather than a biological reality (Davis, 1993). While the social model acknowledges the fluidity of disability, it does not always account for the biology of physical difference and everyday experience of living with a disability (Hughes & Patterson, 1997; Thomas, 2002). However, it does illuminate the consequences of the practices and relationships of people with physical difference with the dominant ableist majority (Thomas, 2002). Disability studies scholars have stressed how social and physical spaces are designed and constructed for the non-disabled person (Hahn, 1996; Titchkosky, 2011; Hanson & Pilo, 2009). The social spaces of sport journalism and elite sport are no exception. According to DePauw (1997), “the lens of disability allows us to make problematic the socially constructed nature of sport and, once we have done so, opens us to alternate construction, actions, and solutions” (p. 428).

Literature Review

The contributions made by early academics in disability studies and media representation have provided foundational critiques of North American media representations of disability as a phenomenon grounded in metaphors of fear, pity, contempt, and charity (Zola 1985; Biklen 1985; Longmore 1997; Clogston 1991; and Darke 1994). Recent disability studies and media representation scholarship, using more critical social science perspectives, have provided nuanced and detailed analysis of disability sport, in particular the Paralympics Games (Thomas & Smith, 2003; Ellis, 2009; Purdue & Howe, 2012). There are three related critical issues from this literature – representations of the Paralympic Games and Paralympians, the Paralympic Paradox (Howe 2008), and representations of gender and disability.

Representation of the Paralympic Games and Paralympians

Sport journalism has historically been grounded in ableist notions of disability as tragedy and the recovery of normal able-bodied life through sport (Duncan & Aycock, 2005; Maas & Hasbrook, 2001; Schell & Duncan; 1999; Schell & Rodriguez, 2001). The journalistic framework, the supercrip, has been dominant in the literature of athletes with physical difference. In works by Howe (2006) and Peers (2010), former Canadian Paralympians, the disempowering effect of the supercrip stereotype and how it celebrates athletic transcendence over the biology of physical difference was studied. The supercrip framework constructs athletic achievement as triumph over the personal tragedy of impairment. This representation is juxtaposed to the “pitiable crip who can’t overcome and the burdensome gimp who won’t” (Peers, 2010, p. 658). According to Hardin and Hardin (2005), the supercrip representation is dominant in sport magazines. Interviews with elite male wheelchair basketball players illustrate athlete acceptance of the supercrip model as potentially positive, despite longstanding criticism of it by the disability community, “In all (sport) magazines, you read articles about able-bodied people doing heroic things…Just because you’re disabled doesn’t mean we can’t read about the good things they’re (disabled) doing” (p. 8). Similarly, Davis (1993) points out how dominant hegemonic messages about disability shape expectations and, how, without an alternate framework, there is little opportunity to construct a different cultural identity.

Current literature on media representation of the Paralympic Games mirrors early work suggesting that the narrative of the personal tragedy of disability is overused. This narrative is also embedded within an overemphasis on “the overcoming of disability” (Thomas & Smith, 2003; Misener, 2102 ) and its counterpart, the stereotype of the supercrip, and the elite disabled athlete. Goggin and Newell’s (2000) analysis of Australian newspaper coverage of the Paralympics Games of 2000 not only demonstrated this narrative of disability, but did so focusing on the narratives of elite disabled wheelchair athletes. Howe (2008), a retired Paralympian, discusses related tensions in his insider analysis of the elite disabled athlete. Howe states that the absence of explanation regarding the classification system used to designate athletes based on functional limitations by the media is done in order to maintain an “elite” status of some disabled athletes. This serves only to reinforce able-bodiedness as the social norm. Thomas and Smith (2003) suggest that comparison of Paralympic athletes with Olympic athletes further promotes an elite status, erases disability and reinforces ableist notions of the Paralympics, which may negatively impact the realization of diversity and equity through sport for athletes with a physical difference. However, Haller (2000) argues that the story of disability when told exclusively by those who use wheelchairs is limited and narrow. She proposes that disability narratives or stories encompass the continuum of athletes with a disability.

The Paralympic Paradox

Purdue and Howe (2012) have explored one of many tensions that exist within the representation of parasport and athletes by conceptualizing the Paralympic Paradox. The paradox is the expression of two social roles that contemporary Paralympians assume. In the first role, the Paralympic athlete engages in elite sport performance by striving to achieve, despite a physical difference. This role is constructed primarily for the non-disabled audience. The second role is that of link or mediator between sport, athletic achievement and physical difference. This socially constructed role target the community of people with a disability. The elimination of disability from representations of the Paralympic athlete may allow non-disabled audiences to see athletes with a disability as athletes, rather than disabled people. However it is physical difference and/or disability that establish credibility of athletes with a disability as role models for non-athletes with a disability. The tension between back-grounding of difference for non-disabled audiences and the foregrounding of difference for disabled audiences is the crux of the Paralympic Paradox.

Representations of Gender and Disability

Review of the literature confirms that quantitatively, more media is constructed regarding male athletes with a disability than female athletes (Thomas & Smith 2003; Goggin & Newell 2005; Sherill 2015). Gender is an important social location that complicates representation and may perpetuate existing gender discrimination (Henderson & Bedini, 1997). This discrimination exists for athletes with physical difference whose race, gender, sexuality, and/or social class exist outside of the dominant majority (Schell & Rodriguez, 2001). During the 1996 Paralympic Games, gender and disability discrimination was evident in the television coverage of American tennis player Hope Lewellen. Lewellen identifies herself as a capable, independent, non-heterosexual woman through her “androgynous physical appearance [which] includes a Mohawk haircut and multiple ear piercings…” (Schell & Rodriguez, 2001, p.567). Unable to reconcile Lewellen’s personal identity choices, CBS ‘managed’ her sexuality, physical difference, and gender by showing her in her kitchen and by questioning her about housekeeping rather than her athletic accomplishments (Schell & Rodriguez, 2001). Ellis (2009) also demonstrated this struggle in her analysis of media/television representation of female Paralympic athletes leading up to the 2008 Paralympic Games. Ellis how Kelly Cartwright, a female athlete who uses a prosthesis, was framed by the camera, focusing on her face and upper body before revealing her prosthetic leg. The decision to highlight her femininity rather than her athleticism is captured in the storyline that focuses on her teenaged interests outside of sport. The work of Buyesse and Borchending (2010) show the marginalization of female athletes during the 2008 Games, identifying the use of passive and feminine appropriate poses in sport photography. The layering effect or ‘double whammy’ (Schnell & Rodriguez, 2001) of gender and disability stereotypes reinforces that male and able-bodied hegemony remains prevalent in sport media.

In summary, the literature regarding media representation of Paralympic Games and its athletes has moved from representations of explicit personal tragedy and narratives of overcoming disability to representations of athletes as athletes with impairment and in some cases, elite disabled athletes. While these representations acknowledge athletic ability, complications are created by the tensions of foregrounding or back-grounding disability for the promotion of elite disabled sport and further complicated by media struggles of how to depict the female Paralympian. Despite these changes in disability sport representation in the media, current representation is still influenced and informed by dominant ableist discourses.

Conceptual Orientation for Analysis

Garland-Thomson’s (2000) work informed and guided the methodology of this project. In Seeing the Disabled: Visual Rhetoric of Disability in Popular Photography (2000), Garland-Thomson uses distance and the spatial relationship it creates to describe four distinct visual stereotypes of disability in photographic images. These visual stereotypes are the following: the wondrous, the sentimental, the exotic, and the realistic. Garland-Thomson contends that each stereotype has been used by the photographic profession to construct images of physical difference that elicit purposeful responses from viewers.

The first stereotype, the wondrous, positions the viewer below the image of disability, inviting the viewer to look up with wonder and awe. Deification constructs disability as something different and removed from normal life. Through this sense of differentness, the viewer begins to covet normalcy and ordinariness. Figure 1 demonstrates this stereotype.

Within the sentimental stereotype, the person with physical difference is placed below the viewer in a position of passivity and dependence; this position may elicit a protective or paternalistic response from the viewer. The sentimental stereotype is used by fundraisers and charitable organizations. See Figure 2.

Garland-Thomson’s (2000) third stereotype is the exotic. A spatial relationship of significant distance is essential to this representation. When seen at a distance, the person with physical difference can be constructed as alien, foreign, and not-like-me. This distance between the viewer and the viewed encourage the acts of staring and objectification of the subject. Garland-Thomson defines “staring [is] an intense form of looking that enacts a relationship of spectator and spectacle” (p. 352). See Figure 3.

The final stereotype is the realistic visual stereotype which establishes a spatial relationship of equality between the viewer and the viewed. Distance is minimized, and physical difference is simply part of the whole. By minimizing but not denying disability, greater social equality is achieved. See Figure 4.

Garland-Thomson’s theory (2000) that representations are social constructions intended to elicit specific responses both informed and grounded this project. The decision to use thematic codes of representation during analysis was influenced by Garland-Thomson’s four visual stereotypes and their effectiveness in the deconstruction of photographic representation. In addition, Garland-Thomson’s concept of staring (Garland-Thomson, 2009) that excludes, objectifies, and denies power was likewise critical to the analysis in this study.

Data Collection and Analysis

Guided by Garland-Thomson’s (2000) modes of looking, her visual stereotypes, and the social model of disability, the research was conducted in two stages. The first stage included selecting, quantifying, and summarizing segments of CBC’s coverage of the 2004 Paralympic Games. The second stage involved in-depth qualitative textual analysis of the segments based on a template (See Appendix A) and thematic codes of representation.

Sampling

Initially, the full 21 hours of CBC coverage was experienced in a home setting. At this point, the first author was a spectator of sport. Included in the 21 hours were the daily CBC vignettes, highlights from previous day/night of competition, commercials, athletic competition, and interviews with athletes. A second viewing of the entire 21 hours of coverage by the first author occurred at the computer with the researcher taking extensive notes guided by Garland-Thomson’s (2000) visual stereotypes: the wondrous, the sentimental, the exotic, and the realistic. Notes taken during this second viewing and Garland-Thomson’s stereotypes facilitated selection of specific segments for analysis. All segments were selected from programming that occurred during primetime hours, specifically Saturday and Sunday. The majority of television coverage – approximately 66% – was broadcast on these days and, within this programming, Garland-Thomson’s visual stereotypes were clearly identified. Commercials were not selected for analysis because they lacked disability-content.

Seven segments of programming were selected for a total of 13 minutes and 7 seconds of broadcast time. Criteria for segment selection required that these segments were initially broadcast on Saturday/Sunday, and that these segments reflected a diversity of sport, gender, and disability. The seven segments included the following: #1 CBC’s Daily Opening Vignette (31 seconds), #2 Kelly Smith and the Marathon (4.51 minutes), #3 Female Chinese Long Jumper (20 seconds), #4 Donovan Tildsley and the Pool (2:01 minutes), #5 Paul Gauthier and Bocce (1:20 minutes), #6 Women’s Goalball Gold Medal Match (1:18 minutes), #7 Chantal Petticlerc and the Track (2:65 minutes).

Data Analysis

The seven segments were analyzed quantitatively to document the extent of diversity. Disability type, gender, sport, ethno-racial diversity and nationality were documented. This information was also used to contextualize the data. All but one segment represented Canadian athletes, thus illustrating CBC’s mandate to showcase Canadian athletes as stated in the CBC Radio Canada Corporate Plan (2006).

Diversity of disability, defined as athletes with sensory and mobility differences, was evident in the segments. At the 2004 Paralympic Games, athletes with intellectual difference did not compete. Diversity of national language, specifically, French and English, was reflected in the segments while ethno-racial diversity was not. In 2004, Canadian Paralympic ethno-racial athletes were almost non-existent.

Content analysis was based on Garland-Thomson’s (2000) criteria of spatial relationship between the viewer and the image and how “difference” was positioned in the image. Imagery, audio and visual effects, and specific production techniques such as camera angle, fades in/out, and colour highlighting were examined in order to refine thematic codes.

Rigour

Data credibility and trustworthiness during the analysis process were strengthened through a triangulation of methods.

An interview with a CBC employee who assisted with the production of the Games was conducted. The interview was significant in that it provided insight into the realities of production associated with a sporting event of this magnitude and confirmed the credibility of the findings of this research.

Additionally, peer review was conducted by members of the first author’s thesis committee, one of whom is a person with physical difference. Member checking of the analysis was performed by two Paralympic athletes who agreed with the analytical process and its findings. The first author was explicit and acknowledged her position as a Caucasian woman, who is non-disabled and has worked extensively as a physiotherapist at multiple Paralympic Games. The first author kept a reflexive journal throughout the project.

Ethics

Ethical approval was provided by the Ethics Review Board of the University of Toronto in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Analysis

Based on multiple viewings of the seven segments, 11 thematic codes emerged from the data. Each code was defined independently and considered to be unique. However, relatedness of some codes and the nesting of codes are acknowledged. The final thematic codes included the following: the athletic, the spectacular, the capable, the sensual, the patriotic, the multi-dimensional, the gendered, the diverse, the supercrip, the non-disabled, and the denied.

In considering this analysis, it is important to remember that language and its associated systems of representation are located within a history, a culture, and a period of time. Saussure (as cited in Hall, 1997), regarded as the father of modern linguistics, argued that words shift in meaning with time, within different cultures and with historical moments. This evolution of meaning can lead to breaking of hegemonic or ableist meanings of language used to represent ability/disability (Goggin & Newell, 2000; Thomas & Smith, 2003; Howe 2008)

Four representations of disability were dominant and recurrent in the final analysis of the segments. These representations were the athletic, the capable, the sensual, and the multi-dimensional. One of the most significant findings of this study involved the nexus of gender, ability, and the body. The importance of these three constructs lies not in their isolation but in their connectedness. The relationship of these important social constructs is discussed in the following paragraphs through an in-depth analysis of the coverage of two Canadian athletes: Chantal Petticlerc and Kelly Smith, both highly successful athletes who competed in wheelchair racing.

A Tale of Two Athletes

Segment 7 tells the story of Paralympic athlete Chantal Petticlerc. Petticlerc is a successful, Caucasian Canadian athlete who excels at track racing. The length of the segment 7 was 2 minutes and 39 seconds. The imagery and text found in the segment constructed a representation of Petticlerc that was almost exclusively athletic. Specifically all coverage of Petticlerc was filmed at the Athletics venue. There were no images of her at home, with friends, or in the television studio. Interviews were brief and occurred at the side of the track. Television commentary dealt exclusively with her athletic experience: the field of competition, Petticlerc’s results, and her four races were shown in their entirety. Petticlerc won four gold medals and set three world records and these statistics were repeated throughout the segment, reinforcing her athleticism almost exclusively. Backgrounding her impairment visually with the use of head and shoulder shots only, an absence of information regarding her physical impairment, represented Petticlerc as potentially non-disabled (Ellis, 2009). The tension of the Paralympic Paradox is illustrated in this highly mediated representation of Petticlerc as an elite disabled athlete (Purdue & Howe, 2012). The absence of text and imagery regarding family, friends, or of life outside of the athletic arena deny a more human, more complex, representation of Petticlerc. The viewer was given a brief opportunity to look at Petticlerc’s body in an inviting manner. Through the use of slow motion photography, the viewer was invited to look and stare at Petticlerc’s very muscular upper body, resulting in a representation of Petticlerc that was spectacular. The camera pulled back from Petticlerc, increasing the distance between her and the viewer. The objectification of her physicality constructed her as physical spectacle or exotic object. This brief, subtle shift in representation of Petticlerc from athlete to exotic spectacle suggests an inability by CBC to avoid ‘othering’ the female athlete. Packer’s work (2014) confirms that during the 2012 London Games, sport media reproduced representations of both Olympic and Paralympic female athletes as ‘other’ or spectacle.

At the end of the segment, Petticlerc was interviewed about her success at the Games. “You know, probably the favourite moment is when I get back to my room and I try to go to sleep and it’s just impossible. I’m just so excited and I just you know. Re-run my race for myself and ah…it’s the best moment….” This interview could have been the opportunity to construct Petticlerc as a person with family, friends, and a life away from the track – as a multi-dimensional human being. The interview, however, was brief, approximately five seconds in length, and suggested that Petticlerc spends her time away from the track savouring her athletic accomplishments. In summary, the CBC represented this accomplished, physically attractive woman in a uni-dimensional way, constructing yet another stereotype – elite athlete only. Petticlerc’s athleticism is foregrounded, increasing her appeal to the non-disabled community, and simultaneously restricting her connectedness to people with a disability by back-grounding or making her impairment almost invisible (Ellis, 2009; Howe, 2008)

Segment #2 presented Kelly Smith. Smith is a Caucasian, male Canadian athlete who like Petticlerc excels at athletics, specifically, long distance wheel chair racing. During the 4 minutes and 31 seconds of this segment, Smith is represented as a fully human, multi-dimensional person. As discussed earlier, there is a nesting of themes within the multi-dimensional representation: specifically, the athletic, the spectacular, the capable, and the sensual.

It is noteworthy that the length of this segment was approximately twice that allotted to Chantal Petticlerc. The work of Smith and Wrynn (2010) of the Vancouver Olympic and Paralympic Games suggests that parity in volume of sport media coverage between the genders is slow to be realized. During these Games, female athletes received approximately 50% less media coverage than their male counterparts.

The athleticism of Smith was constructed using different techniques. Images of Smith in his racing chair dominated the segment. In one instance, Smith was shown racing into Paralympic stadium after the marathon, receiving his silver medal and head wreath. During the commentary after the race footage, Smith described his race strategy this way: “I can climb as good if not better than most of these guys. I got to race my race and (pause) you lose.” In this statement, Smith acknowledged his athletic strengths and challenged his competitors to race “my race” which, according to Smith, they would “lose.” The use of athletic imagery and language asserts his athleticism and competitiveness, confirming an athletic representation of Smith.

The spectacular representation of Smith was constructed through slow motion camera work, soft lighting, and a highlighting technique. Shown in his race chair, Smith was positioned at the front of a pack of racers. His arms and shoulders were outlined in a dark colour highlighting his muscular shoulders, suggestive of a bird’s wings in flight. Through the utilization of soft light and slow motion, Smith was constructed as something other than human, an animal-man flying rather than wheeling his race chair. According to Garland-Thomson (2000) this representation serves to entrench the athlete with disability as exotic and therefore as ‘other’.

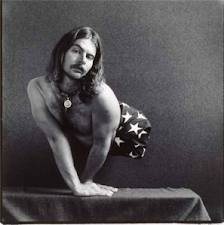

A very masculine, sensual representation of Smith was also constructed by the CBC. Against a backdrop of night, the camera moved to Smith who did not speak but turned slowly in his racing chair, like a model on a runway. The camera then panned the length of his racing chair in a manner that could be perceived as sexually suggestive. He was sitting in his long, sleek racing chair, wearing a sleeveless racing singlet that revealed his strong athletic torso. The viewer was almost compelled to stare at Smith’s muscular body, and to indulge in the sensuality of the man-machine. Representing the sexuality of Smith is evidence of progress within disability journalism, given its historical absence from media regarding people with a disability, especially in representations specific to women with a disability (Ellis, 2009; Duncan & Aycock, 2005).

Through language and imagery, Smith was consistently represented as a capable and a self-directed individual. In an open, forthright manner, Smith spoke of his injury, rehabilitation, and eventual return to sport: “[I] started pushing myself right from the beginning in the day chair, pushing myself to the gym, back and forth and then kayaking….” During the interview, Smith’s body, unlike Petticlerc’s body, was presented to the viewer in its entirety. There was no effort to background his atrophied legs or wheelchair. Smith was seated beside Brenda Irving, interviewer for the CBC, and Irving’s chair was adjusted to match the height of his wheelchair. Looking directly into the camera, Smith engaged the interviewer, the camera, and the viewer with physical and emotional openness. In the next segment he spoke again of his physical difference, and gave words of encouragement to all viewers – those living with or without physical difference. A relationship of equality was constructed between Smith, Irving and the audience:

Too easy for somebody to look at what they can’t do, forgetting about disability. Looking at kids who are comparing themselves…It is universally great message to send not just to kids but to anybody that it is really important to focus on what you can do and to celebrate those achievements with what you’ve accomplished.

This segment is an excellent example of Garland-Thomson’s fourth rhetoric, the realistic (2000). Smith’s physical difference is neither foregrounded nor backgrounded, but an integrated part of the whole. The spatial relationship is one of equality. Smith’s words speak of the universality of difference and need to celebrate achievement, constructing a message of social equality.

Smith was interviewed at the end of the segment and was asked to describe his emotions after the marathon. Smith used this opportunity to define himself as a fully human, multi-dimensional person, “So entering that stadium was incredibly special. Because it wasn’t just about me. You know my parents were there, my brother, his wife and their kid and you know some friends and I know I got some friends back home.” Smith is son, brother, uncle, and friend to people outside the world of athletics, as well as an athlete, and a man with a disability. He is a complex, nuanced person whose disability does not separate him from the social world. Ellis (2009) suggests media representations such as this offer a more comprehensive understanding of disability where disability is an integrated part of the human experience.

Discussion

How Canada’s Paralympic athletes were represented during the 2004 Paralympic Games by the CBC remains significant for a number of important reasons. Positively, since the early 2000s, representations of female and male Paralympic athletes have been growing, in quantity and quality (von Sikorski & Schieri, 2012; Buyesse, 2010). Utilization of the athletic and multi-dimensional representations found in the case study of Petticlerc and Smith are positive alternatives to historically negative representations of athletes with physical difference. CBC’s decision to represent the body of Kelly Smith, a male athletic body with impairment, as sensual is also significant, because of the historical denial of the sexuality of bodies with a disability. The work of Garland-Thomson (2000) and Duncan and Aycock (2005) has demonstrated journalistic denial of sensuality, which therefore highlights how Smith’s physical beauty and sensuality has the potential to broaden definitions of beauty and sexuality, and to reinforce the normalcy of bodies with physical difference. By contrast, the absence of a sensual representation of Chantal Petticlerc in the analysis, subverts the marginalization of female athleticism that historically constructs female athletes in a sexual manner (Ellis, 2009; Buyesse, 2010). However this subversion is problematic in its entrenchment of the asexuality of female Paralympic athletes and women with a physical difference (Sherrill, 1993; Smith & Wrynn, 2010; Packer & Geh, 2014). The analysis discussed within this paper indicates that CBC’s representation of these two Paralympic athletes was generally positive and progressive. However the CBC continued to use traditional representations of female Paralympic athletes, specifically the asexual, that reinforce the dominance of hegemonic masculinity in the world of sport.

The data used in this study was limited to and influenced by the feed provided to the CBC by the host country for CBC’s domestic broadcast. As a result, prior to the author’s interaction with the data, two filters had been imposed. The first included and were impacted by the decisions of the host country’s production network; the second was the CBC’s involvement with the content and construction of the broadcast.

The authors’ recognize that the 2004 Paralympic Games took place 11 years ago and that the findings reported in this paper are based on older data. However, when this current research was conducted, the literature regarding media representation of sport and disability was almost non-existent (Schell & Duncan, 1999). There was little or no research in the review of the literature that was specific to Canadian media and/or Canadian athletes. Of equal significance, it highlights a gender analysis that demonstrates favouring of hegemonic masculinity over femininity within Paralympic sport and sport media. The construction of Kelly as self directed athlete and sensual man embedded in social relationships within and without the athletic community is a powerful alternative representation of the Paralympic athlete; however, this representation was reserved exclusively for the male Paralympic athlete. Unfortunately CBC could not construct a similar representation of Chantal Petticlerc. Packer and Gey (2014) and Smith and Wrynn (2010) argue that little has changed since 2004 for the female Paralympic athlete: they continue to be represented less often and less progressively by the sport media.

Management of physical impairment by the media in the representations of both Petticlerc and Smith is important. Though hidden in the case of Petticlerc and integrated in the multi-dimensional of Smith, the body with a physical difference remains contentious for media. Foregrounding athleticism and hiding disability as in the case of Petticlerc constructed an elite, athletic representation specifically for the non-disabled community (Howe, 2008). In the case of Smith, his physical difference was part of a more complex representation, connecting him to a more diverse social community (Ellis, 2009).

It also is problematic that the representation of the elite Paralympic athlete is exclusive to the athlete in a wheelchair. Haller (2000) argues that the hierarchy within Paralympic sport that favours wheelchair athletes does not reflect the diversity of the parasport experience and people with a disability. This selected disability narrative undermines the efforts of the Paralympic movement towards social equity and normalization of diversity.

Conclusion

The findings of this study confirm that sport media has the ability to construct representations of athletes with impairment and of disability that are progressive and nuanced, as well as representations that entrench stereotypes of the supercrip and female asexuality. The media has the power to locate physical difference along the continuum of human experience, an experience that is not separate from society, and potentially advance social understanding of disability (Ellis, 2009). CBC’s decision to represent Smith as a multi-dimensional, and in the case of Petticlerc, exclusively athletic, was generally progressive. These representations provide alternative ways to conceptualize sport and disability that have the potential to shape how Canadians with physical difference see themselves. Some might argue that these representations are constructions of a particular team of media, specific to a time and place, and therefore less significant. Unfortunately current literature suggests that narrow, stereotypical representations of Paralympic athletes, including that of the supercrip, continue to be reproduced by sport media (Packer & Gey, 2014; Smith & Wrynn, 2010; Thomas & Smith, 2003). However, given the limited opportunity for fans of sport to attend a Paralympic Games, these positive, more human representations remain significant given their potential to influence viewer perspectives and assumptions regarding athletes and persons with physical difference.

There is need for further research to explore the tension that exists between alternative representations of individuals with physical difference and the potential to translate alternative representations for the collective. Sport media needs to reflect the diversity of Paralympic athletes within its coverage and adopt a multi-dimensional, realistic framework for all athletes who are represented by the media. To accomplish this, future research needs to be done to capture the voices of the athlete and their experience of sport and disability. It is essential that the lived experience of athletes with diverse abilities inform the sport media industry to ensure that the “enduring neglect of disability” is reformed (Golden, 2003; Goggin & Newell, 2003).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to recognize the media staff of the Canadian Paralympic Committee who work tirelessly to construct representations of Canadian Paralympians that are realistic and multidimensional. Special thanks are extended to Dr. Lorraine Carter.

References

- Biklen, D. (1985). Framed: Print journalism treatment of disability issues. Social Policy, 6, 79-85.

- Buysse, J.M. (2010). Framing gender and disability: A cross cultural analysis of photographs from the 2008 Paralympic Games. International Journal of Sport Communication, 3, 308-321.

- Davis, L.R. (1993). Critical analysis of the popular media and the concept of ideal subject position: Sports Illustrated as case study. Quest, 45(2), 165-181.

- DePauw, K.P. (1997). The (in) visibility of disAbility: Cultural contexts and “Sporting Bodies.” Quest, 49(4), 416-430.

- Darke, P. (1994). Understanding cinematic representation of disability. Social Policy, 181-197.

- Duncan, M., & Aycock, A. (2005). Fitting images. Advertising, sport and disability. In Jackson S. J., & Andrews D. L. (Eds.), Sport, culture and advertising. Identities, commodities and the politics of representation. (136-153). London, UK: Routledge.

- Ellis, K. (2009). Beyond the Aww Factor: Human Interest Profiles of Paralympians and the Media Navigation of Physical Difference and Social Stigma. Asian Pacific Media Educator, 19, 23-35.

- Employment and Social Development Canada. (2012). Canadians in Context-People with Disabilities. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Employment and Social Development Canada.

- Garland-Thomson, R. (2009). Staring: How we look. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Garland-Thomson, R. (2000). Seeing the disabled: Visual rhetorics of disability in popular photography. In P. Longmore, & L. Umansky (Eds.), The New Disability History: American Perspectives. (pp. 335-373). New York: New York University Press.

- Goggin, C., & Newell, C. (2000). Crippling Paralympics: Media, Disability and Olympism. Media International Australia.97:71-84.

- Goggin, G., & Newell, C. (2003). ‘Digital disability.’ The social construction of disability in new media. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Hahn, H. (1996). Antidiscrimination laws and social research on disability: The minority group perspective. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 14(1), 41-59.

- Haller, B., Dorries, B., & Rahn, J. (2006). Media labeling versus the US disability community identity: a study of shifting cultural language. Disability & Society, 21(1), 61-75.

- Hansen, N. & Pilo, C. (2009). The Normalcy of Doing Things Differently: Bodies, Spaces and Disability Geography. In T. Titchkosky & R. Michalko (Eds.), Rethinking Normalcy: A Disability Studies Reader (251-269). Toronto. Canadian Scholars Press.

- Hardin, M., & Hardin, B. (2005). Performance or participation… pluralism or hegemony? Images of disability and gender in Sports'n Spokes magazine. Disability Studies Quarterly, 25(4).

- Henderson, K., & Bedini, L. (1997). Women, leisure, and “double whammies”: Empowerment and constraint. Journal of Leisurability, 24(1), 36-46.

- Howe, P.D., & Jones, C. (2006). Classification of disabled athletes: (Dis)empowering the Paralympic practice community. Sociology of Sport Journal, 23(1), 29.

- Howe, P.D. (2008). From Inside the Newsrom Paralympic Media and the “Production of Elite Disability”. http://irs.sagepub.com/content/43/2/135.short.

- Hughes B., & Paterson K. (1997). The Social Model of Disability and the disappearing body: Towards a sociology of impairment. Disability & Society, 12(3), 325-340.

- Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. (2010). Federal Disability Report. Gatineau, QC, CA: Human Resources and Skills Development Canada.

- Longmore, P. K. (1987). Screening stereotypes: Images of disabled people in television and mot ion pictures. In Gartner, A, & T. Joe (Eds.) Images of the disabled, disabling images. (65-78). New York: Praeger.

- Maas, K. W., & Hasbrook, C.A. (2001). Media promotion of the paradigm Citizen/Golfer: An analysis of golf magazines' representations of disability, gender, and age. Sociology of Sport Journal, 18(1), 21-36.

- Misener, L., Darcy, S., Legg, D., Gilbert, K. (2013). Beyond Olympic Legacy: Understanding Paralympic legacy through a thematic analysis. Journal of Sport Management, 27, 329-341.

- Packer, C., Gey, D., Golden,O., Jordan, A., Withers, G., Wagstaff, A., Bellwood, R., Binmore, C., Webster, C. (2014). No lasting legacy: no change in reporting of women’s sports in the British print media with the London 2012 Olympics and Paralympics. Journal of Public Health, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 50–56

- Peers, D. (2009). (Dis) empowering Paralympic histories: Absent athletes and disabling discourses. Disability & Society, 24(5), 653-665.

- Purdue, D.E.J. & Howe, D. (2012). See the sport, not the disability: exploring the Paralympic paradox. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health, 2(4), 189-205.

- Schell, B. L. A, & Rodriguez, S. (2001). Subverting bodies/ambivalent representations: Media analysis of Paralympian Hope Lewellen. Sociology of Sport Journal, 18(1), 127-135.

- Schell, L. A., & Duncan, M. C. (1999). A content analysis of CBS’s coverage of the 1996 Paralympic Games. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 16, 27-47.

- Silva, C. F., & Howe, P. D. (2012). The (in) validity of supercrip representation of Paralympian athletes. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 36(2), 174-194.

- Smith, M., Wrynn, A. (2010). Women in the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games: An Analysis of Participation, Leadership and Media Opportunities. A Women’s Sports Foundation Research Report. New York.

- Thomas, C. (2002). Disability theory: Key ideas, issues and thinkers. In Barnes, C., Oliver, M., & Barton, L., Eds. Disability Studies Today. (pp. 38-57). Malden, Maine, USA: Blackwell Publishers Inc.

- Thomas, N. & Smith, A. (2003). Preoccupied with Able-Bodiedness? An Analysis of the British Media Coverage of the 2000 Paralympic Games. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 2(2), 166 -181.

- Titchkosky, T. (2011). The Question of Access: Disability, Space and Meaning. Toronto. University of Toronto Press.

- Titchkosky, T. & Michalko, R. (2009). Rethinking Normalcy: A Disability Studies Reader. Toronto. Canadian Scholars Press. P. 352.

- Tynedal, J., & Wolbring, G. (2013). Paralympics and its athletes through the lens of the New York Times. Sports, 1 (1)1, 3-36.

- von Sikorski, C., Schieri, T., Moller, C., Oberhauser, K. (2012). Visual news framing and effects on recipients attitudes towards athletes with physical difference. International Journal of Sport Communication, 3, 69-86.

- Wolbring, G., & Tynedal, J. (2013). Pistorius and the media: Mist, story, angles. Sports Technology, 6(4), 177-183.

- Zola, I. (1985). Depictions of disability-metaphor, message, and medium in the media: A research and political agenda. The Social Science Journal, 22(4), 5-17.