That’s My Story and I’m Sticking To It

Cindy Scott

Huronia Speakers Bureau

Transcribed and compiled by Jen Rinaldi

University of Ontario Institute of Technology

Abstract

Cindy Scott is a proud lesbian woman and a survivor of the Huronia Regional Centre (HRC), an institution that housed persons diagnosed with intellectual disabilities 1876-2009. She is known for her work in Orillia, Ontario speaking about institutionalization and on behalf of residents who died and were buried in the cemetery on HRC grounds. For the past four years, Cindy has been a co-researcher working with Recounting Huronia: a collective of researchers, artists, and survivors using arts-based and storytelling methods to return to and preserve lived memories of the HRC. The research team often operated in pairs, in monthly workshops that used scrapbooking, poetry, cabaret performance, and other arts-based methods to articulate traumatic memories. The stories told here came from workshop exchanges between Cindy and fellow Recounting Huronia member Jen Rinaldi, and are anchored in scrapbook entries they developed together in Recounting Huronia workshops. Cindy retold these stories for Jen to transcribe, and Jen has provided some context via footnotes.

Keywords

- Oral history

- institutionalization

- scrapbooking

- arts-informed methods

- trauma

That’s My Story and I’m Sticking To It

Cindy Scott

Huronia Speakers Bureau

Transcribed and compiled by Jen Rinaldi

University of Ontario Institute of Technology

Cindy Scott is a proud lesbian woman and a survivor of the Huronia Regional Centre (HRC), an institution that housed persons diagnosed with intellectual disabilities 1876-2009. She is known for her work in Orillia, Ontario speaking about institutionalization and on behalf of residents who died and were buried in the cemetery on HRC grounds. For the past four years, Cindy has been a co-researcher working with Recounting Huronia: a collective of researchers, artists, and survivors using arts-based and storytelling methods to return to and preserve lived memories of the HRC. The research team often operated in pairs, in monthly workshops that used scrapbooking, poetry, cabaret performance, and other arts-based methods to articulate traumatic memories. The stories told here came from workshop exchanges between Cindy and fellow Recounting Huronia member Jen Rinaldi, and are anchored in scrapbook entries they developed together in Recounting Huronia workshops. Cindy retold these stories for Jen to transcribe, and Jen has provided some context via footnotes.

Jen Rinaldi: Why do you want to tell these stories?

Cindy Scott: People need to hear the story, what’s going on. I want survivors to hear my story, and I think they want to hear about it. It will be sad for them but survivors want to hear about it because it’s important for them. And the people need to hear about us. People try to label us mentally retarded. I think people want to hear about the HRC survivors, how they did survive, how they got out of there.

JR: Is it important to you that these stories be told? Does sharing your experience help you?

CS: Yes, it helps to get the story out. It’s always inside me. I saw what I saw. It makes me feel upset. It helps me to tell people the truth. How did I ever survive the HRC? I tell people, and it’s the true story. I live it every day of my life. It’s like a trauma in my head—it’s always there. It’s never going to stop. I live with that every day.

That place has never changed. The wall’s still green, that building has been sitting there for decades. And my life is still difficult. There’s still institutions. People need to understand what the institution is all about.

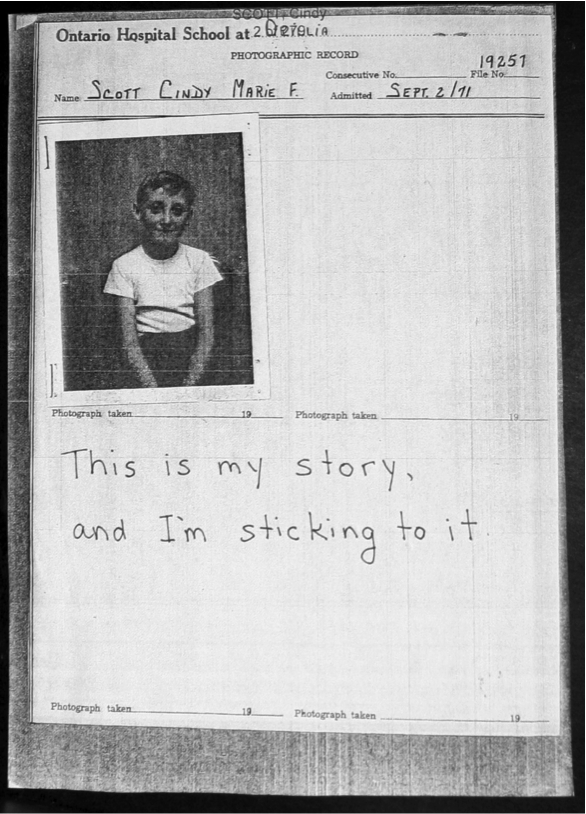

JR: Can you tell me about this intake photo [Fig. 1]?[1]

CS: That little photo I have from the HRC. I remember when they took that picture of me, I did not want to smile. The staff kept saying “Smile, smile!” and I gave them a dirty look. I didn’t want to smile at all. I was not very happy at the HRC.

I was seven years old when my mom put me in the HRC. It’s not like a nursing home or daycare.[2] The room we were in had 16 beds, and a washroom. They put me in a nightgown, they made me take my clothes off. You have to leave your underwear on. All the kids are rocking back and forth, playing with their fingers, yelling and screaming. They had TV and that was it—no toys or nothing. We had to sit on the floor.

JR: Did you have any day-to-day jobs?

CS: At lunchtime, everybody had hot dogs, and I helped feed the younger kids and severely handicapped kids. I had to help them to eat, like hold a spoon for them. The staff didn’t want to because they wanted us to do it. We had hot dogs and porridge. I didn’t like it. We had plastic cups with juice. They put powdered milk that would get clumpy.

One time I was feeding them, one of the patients, and there was a piece of glass in the hot dog. I was watching her and I saw the piece of glass. I grabbed her hot dog and she had my hot dog instead. I had to throw hers in the garbage. I was about nine or ten. I was feeding them in the afternoon.

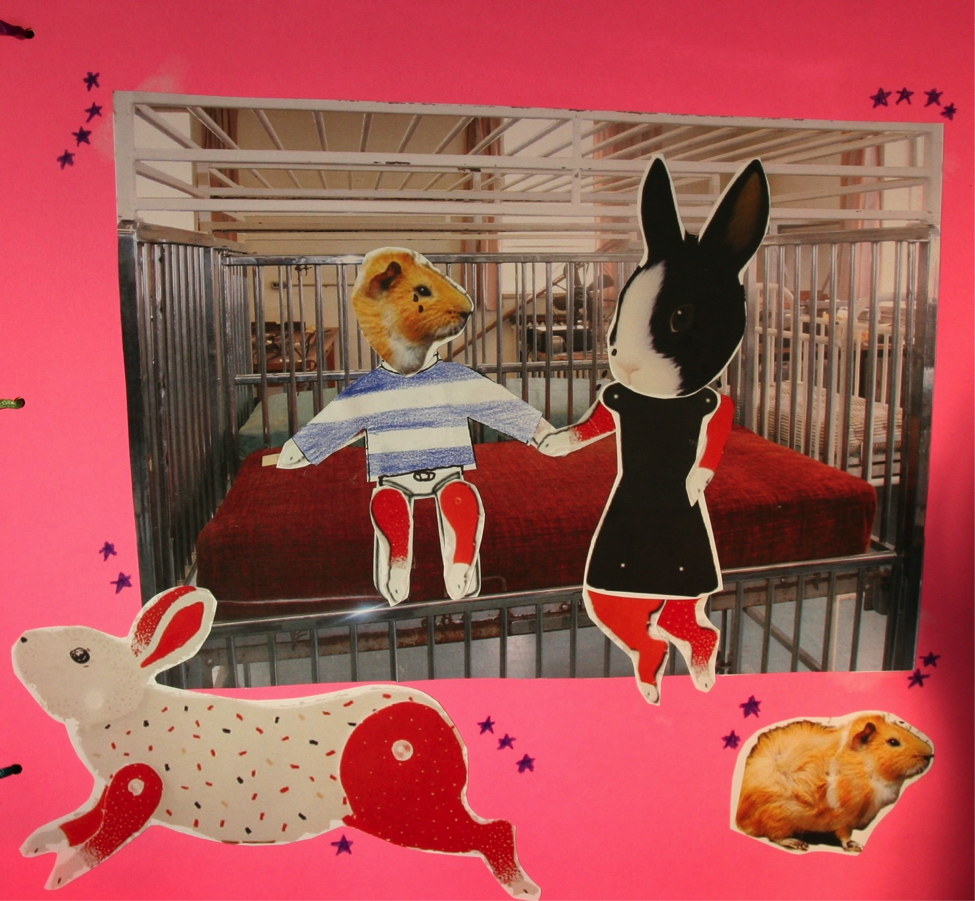

JR: Would you like to tell me about this picture [Fig. 2]?

CS: My best friend Colin, he was in bed for a long time. I said to one of the staff, “Why don’t you let him out?” “Don’t worry about him, just leave him,” the staff tells me. That’s what he said. I remember Colin and I were holding hands through the bars,[3] and he was crying. He looked me in the eye. He was wearing a diaper and blue and white striped T-shirt and a hat. Not a helmet, more like a rubber hat. He wasn’t doing anything, just sitting in bed. He was caged up and holding my hand through the bar. I cried with him. We both cried.

I don’t know whether he’s dead or alive. I only know his first name, can’t remember his last name. I think about him all the time but I don’t know if he’s around Orillia. I don’t know if he lived.

The staff, understand, they did not treat other kids well. This one girl rocking back and forth on the bed, they put a straitjacket on her.[4] One lady held both feet and two male staff put the straitjacket on her. It made me feel very sad. I didn’t know why they were doing that—she was just rocking, not hurting anybody.

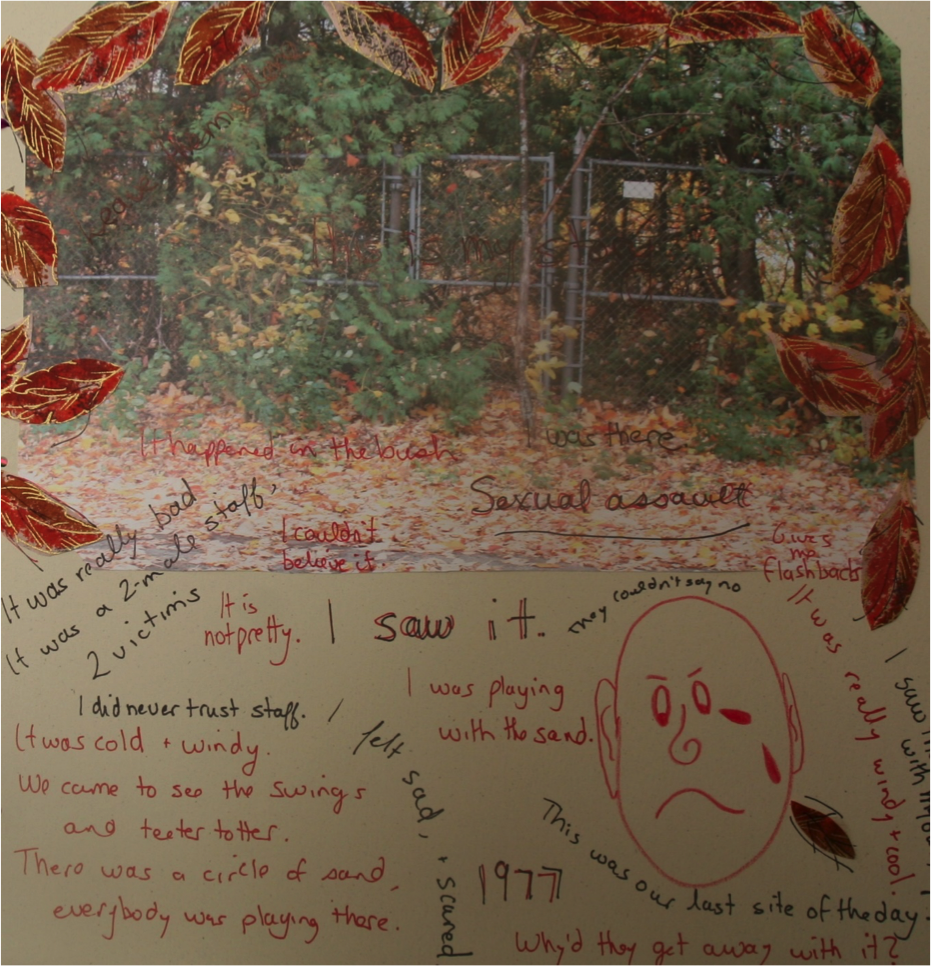

JR: What is the story behind this work [Fig. 3]?

CS: I was in Cottage D[5] at the time. When I was seven I saw two male staff take two girls in the bush when I was outside playing in the sand. One old guy came out from the bushes and pulled up his pants, and the other one, the younger staff, he’s kind of got his shirt out and had to tuck it in his pants. I knew what they were doing. The girls, they wouldn’t understand anything sexual; they don’t know how to say stop or no, or can’t even walk away. They were severely handicapped people. They couldn’t even talk. The way I know, the way they sit, they couldn’t sit down, like they hurt themselves.

Of course they would get pregnant and they would go down to the hospital beds in the tunnel and have the babies taken out of them. The babies were burned and put in the back in the baseball field.[6]

I went inside and the staff pretended nothing happened. And that’s pretty sad. The girls were severely retarded. They were not able to speak at all. After that everybody sat down and watched TV.

I remember a bathtub that was round and tall. There were seven male staff, all looking at my body. I was naked. I had no breasts at the time—I was maybe 12, 13 years old. The staff were all looking at me, my body. I was naked and there’s a man holding a green hose up my arse. The staff blew water up in my stomach. And I came out and the guy was laughing. I asked, “What are you laughing about?” and he just sticks out his thumb and says “Go back to your room.”

One time, I was in a male staff’s office. I had a hospital nightgown, and he was trying to pull its strings. He wanted me to go up on the bench. You know those hospital beds that put your legs up? I knew he was going to rape me there. I got out of there when another male staff came in the door wondering what he was doing. I wanted to go to my room and hide.

I was always watching. What are they going to do with me next? Staff screaming, yelling. They would abuse me. Try to have sex with me.

JR: Is there anything more you want to have included in your story?

CS: I survived, I survived. I lived to be part of these people. Be retarded. One that’s not normal.

People don’t care about retarded people. They dump the bodies and don’t give a shit. Staff don’t give two shits, don’t give a damn about Huronia people.

I stay in my apartment; I never go out. I don’t socialize with people, because of the way they treat me. I just don’t trust men. My life is still difficult. Sometimes I cry, and I like to be left alone for a little while, with my mom. Every time I go up there to Huronia, to the gravestones,[7] I think about them. I sit at the gravestones and tell them I’m sorry. I sometimes tell them I wish I was dead too.

That’s my true whole story right there.

-

This photograph was taken when Cindy was first admitted to the Huronia Regional Centre as a child. She would reside at the HRC for seven years. ↑

-

Here Cindy is drawing a contrast between what she remembers to be intolerable living conditions in an institutional setting and the conditions in far more innocuous spaces like daycare centres, but she has in other correspondences expressed the concern that problematic, even violent, institutional practices carry through to care-based and residential services for persons with disabilities and senior citizens. ↑

-

Cindy is referring here to a crib cot: a bed with bars along all sides and a canopy of bars overhead. These beds are reminiscent of animal cages. So Colin would have been in bed a long time, and Cindy would have asked staff to let him out, because the bed’s walls enclosed him. ↑

-

Straitjackets bind a person’s arms by wrapping the sleeves around the body. ↑

-

Cottage D is a building that housed residents on Huronia Regional Centre grounds. ↑

-

While this claim has yet to be verified, it is important to highlight here: traumatic memory—even the memories not yet supported with evidence—necessarily carries truth. These are the memories that continue to affect Cindy, and that tell us at minimum this truth: the Huronia Regional Centre was a place of horror. ↑

-

There is a cemetery on HRC grounds that holds the bodies of residents who died while institutionalized there. ↑