Self-Advocacy from the Ashes of the Institution

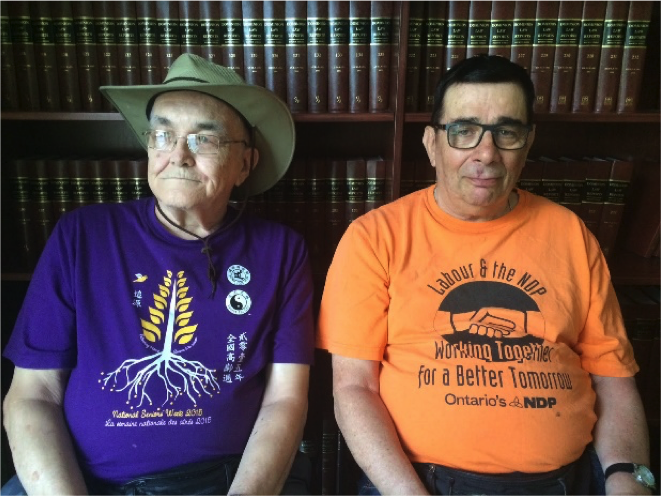

Sue Hutton

ARCH Disability Law Centre

Peter Park

Human Rights Activist

Martin Levine

Self-Advocate

Shay Johnson

York University

Kosha Bramesfeld

University of Toronto

Abstract

This paper explores the oral histories of two survivors of Canada’s institutions for persons labelled with intellectual disability. Both of these men survived the abuses of the institutions and went on to become committed to rights advocacy for others labelled with an intellectual disability. They were determined to tell their stories and act as change agents so that no one else experiences the abuse they did. In this paper, Peter and Martin tell parts of their stories, including their journey toward self-advocacy. This paper provides a space for these truths to be revealed in the time of class action law suits that are underway for these survivors. No opportunity was provided for the class action members to tell their stories in court, so this paper contains pieces of the narrative that survivors want people to know. Their stories are told in both narrative and art form. These artifacts highlight common themes of institutional abuse and isolation, but also of remarkable resiliency and strength. Their stories serve as an important record of the history of institutionalization in Canada and help to shape a better understanding of the roots of self-advocacy, including the importance of “nothing about us without us” (Charlton, 1998).

Keywords

- Self-advocacy

- human rights

- institutionalization

- intellectual disability

- disability advocacy

Self-Advocacy from the Ashes of the Institution

Sue Hutton

ARCH Disability Law Centre

Peter Park

Human Rights Activist

Martin Levine

Self-Advocate

Shay Johnson

York University

Kosha Bramesfeld

University of Toronto

The authors would like to thank Petra Asfaw, Loris Bennett, Kerri Joffe, and Fahima Zaman for contributions to the manuscript. Special thanks go to Nelson Caetano for artistic consultation on visual data.

This paper brings to light the stories of survivorship of Peter Park and Martin Levine, institutional survivors who went on to become committed to advocacy for others. Similar to the documented histories of other survivors of Ontario institutions (Joffe, 2010), their stories, told in narrative and art form, have pain in them, and reveal dark truths of life in the institutions. They also shed light on the hope that Martin and Peter’s resilience and mobilization toward self-advocacy hold. A unique aspect of Martin and Peter’s stories is that, in addition to the written narratives of their experience, Martin and Peter worked with social worker Sue Hutton to visually document through pencil drawings some of their most intense memories. These pencil drawings highlight the emotional impact of Martin and Peter’s experiences and serve as rare visual documentation of the abuses that were suffered. This visual documentation serves to contextualize the survivor’s experiences in ways that words cannot fully portray (Springgay, Irwin, & Wilson Kind, 2005). Importantly, the rendering of these experiences in visual forms increases the accessibility of these narrative histories to individuals who may not be capable of reading survivor stories in written form.

To provide context, Martin and Peter’s narratives are grounded in a review of the history of institutionalization and are then followed up with a discussion of Canada’s self-advocacy movement. Ultimately, this paper seeks to provide a space for Martin and Peter’s stories to be shared so that they can continue to advocate for their human rights along with the rights others. By including the perspective of survivors—up until now hidden from history— we seek to broaden the understanding of the wrong-doings of the past and alter the path ahead with a focus on advocacy, dignity, and human rights. These stories add to the body of knowledge that is emerging from survivors across the country. Peter and Martin’s stories add to these narratives by explicitly discussing the paths that they took to engage in activism as survivors of institutions. Their stories emphasize the importance of empowering people labelled with intellectual disabilities.

Canada’s Dark Past: Our History of Institutionalization

In 1876, institutions were placed under the responsibility of the Canadian provinces. In that same year, the Ontario Ministry of Community and Social Services (MCSS) opened Ontario’s first institution for people labelled with an intellectual disability in Orillia (MCSS, 2012), later known as the Huronia Regional Centre (MCSS, 2014). For many years following, institutions continued to open across the province to meet a growing demand to institutionalize persons labelled with an intellectual disability in isolated settings away from the public eye. This period of institutionalization represented a dark and enduring history of dehumanization and human rights violations in Canada that left deep scars on thousands of people.

The flood of stories of abuse came crashing down in 2013 in a class action law suit that brought to light what had been long waiting in darkness. The Huronia class action lawsuit launched by two courageous survivors, Patricia Seth and Marie Slark, highlighted the severity of the mistakes that the government made in funding this ongoing abuse. In December 2013, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice approved a $35 million settlement between the survivors of Huronia Regional Centre and the Ontario government (Seth, Slark, Boulanger, & Dolmage, 2015). No more than six days later the Ontario government issued a formal apology to the former residents of Huronia Regional Centre. This apology recognized that the residents of this institution endured forcible restraints, were stripped of their dignity, and underwent physical and emotional abuse (MCSS, 2014).

Despite the disgraceful treatment, few researchers have provided insight into the lived experiences at Ontario institutions (Seth et al., 2015; Hutton, Park, Park, & Rider, 2011). No opportunity was provided for the class action members to tell their stories in court. Local newspaper articles highlighted the memories of individuals who resided in institutions (Marlin, 2010; McKim, 2009), however, there is a need for formal documentation regarding the conditions of these institutions and the impact they had on those who survived them (Lemay, 2009; Rossiter & Clarkson, 2013).

Nothing about Us without Us: The Need for Inclusive Research

Providing people labelled with intellectual disabilities the space to broadly share their experiences has yet to become a priority within Ontario. Indeed, research within the field of disability is mainly conducted by people who do not have a disability, further disempowering an already vulnerable population (Coons & Watson, 2013). Existing literature promotes value in conducting inclusive research as it allows persons with disabilities to be involved in every step of the process (Coons & Watson, 2013; Johnson, Minogue, & Hopklins, 2014; Kidney & McDonald, 2014). This inclusive model of participatory research validates the experiences of people labelled with intellectual disabilities and gives them much needed control over what the field of disability research is portraying about the population. A phrase often heard in People First language that first emerged in the James Charlton book of 1998 is relevant to ethics and research with this population: “nothing about us without us” (Charlton, 1998). It is all too often that people labelled with intellectual disabilities are actively excluded when important decisions are made about their lives. The stories of Peter and Martin’s institutionalization demonstrate these breeches of human rights and dignity.

This paper shares the stories of Peter and Martin who were both behind the bars of an institution in 1974, Ontario’s peak year of housing people labelled with intellectual disabilities in institutions. There were over 10,000 children and adults labelled with an intellectual disability locked away at that time (MCSS, 2012a). In total, over 50,000 people were institutionalized in Ontario prior to the last institutional closure in 2009 (MCSS, 2012a). Peter and Martin’s stories serve as an important record of the history of institutionalization in Canada and help to shape a better understanding of the roots of self-advocacy. The stories of Peter and Martin of being excluded from decision-making in the institution shine a light on the reality that people labelled with intellectual disabilities were pushed aside and their lives were determined for them by others.

Methodology

This paper uses oral history to shed light on institutional survivorship. Two of the authors of this paper, Peter and Martin, who are self-advocates and survivors of Ontario institutions teamed up with social worker Sue Hutton at ARCH Disability Law Centre to tell their stories. The team met to talk about the best way to document these stories. Survivors provided consent in plain language to have their stories published. Importantly, the consent form outlined in plain language the process in case the decision was made to withdraw from the writing of the paper (Horner‐Johnson & Bailey, 2013). Consistent communication was necessary given the potential trauma in re-telling of the stories and the fact that co-authorship would reveal their identities.

We ensured that the process of writing the paper was as accessible as possible in multiple ways. For the narrative section, the group met over a period of six months to gather the stories. Each time the story would be read back and changes were made as needed. The stories were initially recorded on video for survivors to listen back to and correct. Stories were transcribed to paper and read with survivors again. During the transcription and revision process, care was given to ensure that the narratives were understandable but captured the original voices of the survivors. As much as possible the original wording of the survivors was maintained, even though it meant the inclusion of the occasional grammatical error. When language needed clarifying, Sue would suggest words, and if accepted, these words were used.

Interviews focused on two broad questions: “What was life like in the institution?” and “What is life like now?” To help the survivors elaborate on the first question, follow-up questions were asked, such as, “How and when were you admitted?”, “What was your connection to family?”, “How and when did you leave?”, and “What has life been like since getting out?” These questions were used to guide the interview, but emphasis was put on providing the narrators with the opportunity to speak about what they felt people should hear above and beyond the questions.

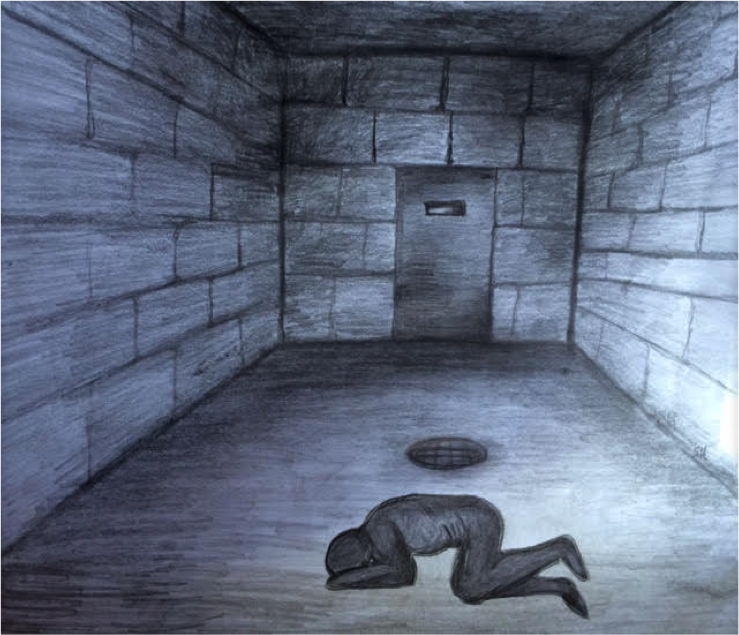

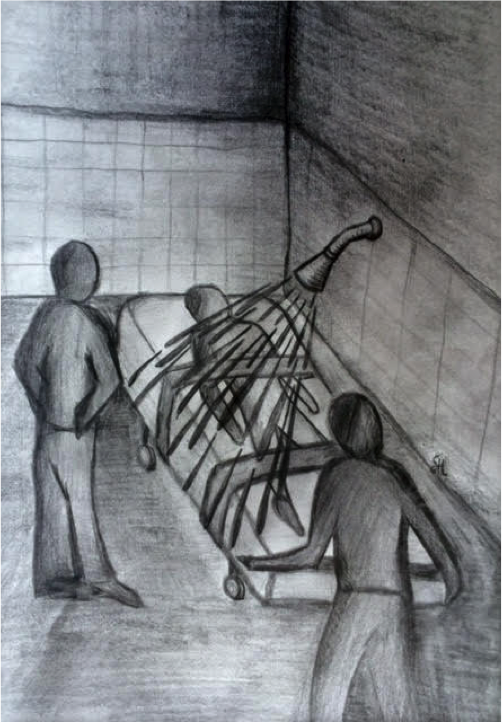

In the process of documenting the narratives, Peter Park requested that images of particularly deep and difficult memories be included with the narrative tellings so that these stories of survivorship could be made accessible to individuals who are not able to read. Based on this suggestion, Sue worked with Peter and Martin to convey some of the memories from their stories in visual format. The survivors described how things looked and provided guidance in creating the image to their satisfaction. Sue created a sketch from the words of the survivors. For example, Sue would pause and ask what position they were in and where things were in the room. She would sketch them out and ask if what was captured was correct, and would make corrections as necessary. Both men felt that it was very important to include graphic depictions—as the abuses of institutions are, to our knowledge, not often visually recorded. Both men shared very vivid visual recollections associated with the memory and continued to give instructions until they felt that it was complete. Peter suggested having a graphic depiction of him in “D Ward” where he was kept in isolation for so much of the time that he was incarcerated. Similarly, Martin requested to have an image of him being subjected to what he called water torture. Both men requested this in order for people to see an image that would never have been captured otherwise.

The opportunity to process their experiences in art form added richness and depth to the survivors’ stories. Indeed, art as a form of inquiry can provide survivors with a method to make sense of and create meaning from questions that lack linear or straightforward answers (Springgay et al., 2005). For this reason, the process of developing the images was one of support. The time was taken for Peter and Martin to share any feelings that they wanted to share about the trauma depicted in the images. The pain of these moments is deeply evident in the images themselves, as well as the narrative stories that accompany these images.

The experience of having an ally document such egregious harm for a survivor is one that requires immense confidence. The relationship between all three is one of trust. Peter, Martin and Sue all met through advocacy work at a developmental services organization in Toronto. Peter and Sue met in 2006 when Peter’s wife was on an advocacy committee that Sue worked with. Peter and Sue got to know each other quite well. They shared so many views and wrote an article together on tokenism that was published in the Journal of Developmental Disabilities in 2011. Sue has known Martin since 2013, and they got to know each other through advocacy work regarding the class action law suit for Huronia. It was with this foundation of trust that this article was co-authored.

Peter’s Story

Background. Peter was institutionalized in the Oxford Regional Centre (ORC) in Woodstock at the age of 20 when his family received medical advice that living in an institution would be the best support for Peter who was diagnosed with epilepsy. Peter survived 18 years in the Oxford Regional Centre. It was 1961 when he entered the institution. He did not get out until 1978. The place Peter was detained, the ORC, first opened in 1905 as the Epileptic Hospital (MCSS, 2012b). It is one of the oldest provincial institutions in Ontario (MCSS, 2012a). Residential support was provided to people with epilepsy and tuberculosis (MCSS, 2012b). Later, the institution also housed people labelled with an intellectual disability. By 1974 it became known as the Oxford Regional Centre after having been renamed the Ontario Hospital School, Woodstock in 1919, and then again the Oxford Mental Health Centre in 1968. In 1974, the facility housed 683 residents. It finally closed its doors in 1997 (MCSS, 2012b). Public information on the history of the Oxford Regional Centre is scarce. The scarcity of information about this institution further highlights the need to document stories from survivors in the interest of historical record.

In Peter’s words. Well, to start with, human rights were basically non-existent in the institution. I really had no choice but to do something about how bad things were for people with intellectual disabilities after being in there so long. I had to. I was bound and bent that no one would ever, ever have to go through what I went through in there. You can’t even say I “lived” in the institution. I simply existed. We weren’t treated as human, in every single way.

When it all started. I was 20 years old and I remember my family and I heard about an institution. We sure weren’t given the whole story. The one I went to ended up being Oxford Regional Centre. Two doctors were there when we talked about it—I remember that part well. The question was asked, “Can I leave anytime I want to?” It was so important to me to be able to leave. I was told I could leave anytime I wanted.

My mom and dad, sister, next-door neighbour were there at the meeting. I had epilepsy—seizures. This is what we were talking about. These two idiot doctors said they could cure my seizures.

Then, once I was in there, I couldn’t leave. Once I was inside, I saw how bad it was in there. I just wanted to get out. My paper that said I could leave whenever I wanted to was lost. I was a prisoner now. Except doing time in an institution is worse than jail. In a jail you are treated better than you are in an institution. When you go to jail, you know when your time is served. In an institution you might have a life sentence. But you don’t know day to day. They are all lying to you and you don’t know the truth. You have no rights at all, not even to privacy in the institution. You just don’t know when you are going to get out, if ever. And you didn’t even commit a crime.

My father was trying to get me out of the institution after I had been in for about sixteen years. My dad was a pharmacist. He almost lost his business trying to get me out. He even went to court to try and get me out. That didn’t even work. They wouldn’t let me out. I believe that they were making money per head and didn’t want to let me go. We were guinea pigs and they were using us, making money off us. All that medication that they tried out on us. I tried to leave many, many times. I remember one time well. It was the most memorable time I tried to leave.

I wanted to go home and go down to our cottage. Needless to say, I didn’t get to go. I outwitted the institutional staff for a while. I ran away and I stayed in the nearby town of Woodstock for a while. I took my baseball glove and walked down pretending I was going to go down to where the field was to play baseball. And I just kept walking until I was out and they didn’t see me walk by. Escaping was constantly on your mind—all the time thinking of how to escape.

I knew a family was away, so I hid out in their garage. I didn’t have any money because the institution had it all locked up, so crackers was all I could eat. I kept a supply of crackers for times like this. The food was so terrible, so I kept crackers hidden away in case the pig swill they served was so bad that I couldn’t eat it. We would buy our own food and mainly what was there was crackers, and maybe sometimes a can of spam.

Over and over I tried to escape like that. They’d catch me and I’d get punished. Didn’t stop me from trying.

Visits with my family were controlled. I remember a funny story when my brother Bob came to visit me. It was against the rules of the institution for family to visit without telling them. He just showed up to visit me because he was in the area. That time my brother got to see what it was actually like behind the scenes. On Sundays, the day family was allowed a controlled visit, the staff put out flowers and books and personal items. It was worse than a hospital because you had no privacy whatsoever. There were about 13 inches between each bed and about 12 beds in each room. Bathrooms were open with no privacy at all. The toilets were lined up beside each other. You can imagine what five toilets all in a row was like in an overcrowded institution. They didn’t want family to see what it was really like.

And listening to the outside world, knowing what was going on in the world, wasn’t an option. There was only a radio that they controlled. Later, there was a television that they controlled. There was no reading material out. They forced us to go to bed at 8:30. It was awful because at that time I really liked to listen to the hockey games. Gordie Howe was on the ice, the Mahovolichs and I wasn’t allowed to watch it. They finally got a television. I was a grown man and they put on Donald Duck. Nothing important to keep us educated about what was going on in the world.

Because my dad was a pharmacist, he gave me a CPS[1] and a Merck Manual.[2] I wouldn’t take any medications they tried to force on me unless they were listed in the Merck Manual. I was sent to the D Ward so often for refusing to take medication. I think that of my 18 years, I was locked up for nine of them. Between running away and refusing to take medication I did a lot of time in D ward.

In D Ward they strip you of your clothes so you’re bare. The walls are bare concrete. The floors are bare. Just concrete. No bed, no chairs. If you were lucky and the doctor said you needed one, you might be lucky to get a small mattress. I was normally on the concrete floor. I think the longest time I was in might have been four or five days’ straight. I don’t really know because there was no clock. The door to the room is always locked. There’s a little tiny sliding window they look through at you sometimes when they want to observe you. The doctor, the staff look through at you. You had to stay in view of the tiny window so they could easily observe you. If you moved to a different part of the room and they couldn’t see you—they’d punish you. They would say, “Okay—you moved from your spot—that’ll be two more days of D Ward for you.” There was an open drain in the middle of the floor. Because there was nowhere to go to the bathroom, if you couldn’t get the attention of the staff, you’d have to just go right there in the drain. Then you would have to lie close to it or you would get punished. The odour of it—you just got used to it. Like the hard floor, you just got used to it, became numb to it because there was nothing you could do about it.

One day in the showers my friend physically died right beside me. He was one of three friends I made while there. I watched him die. And the staff said he had only taken a seizure. He was talking to me for one moment and the next moment—I think it was a stroke. The staff told me it was a seizure, but it wasn’t. Death is different than a seizure. I saw people being shipped off to Penetanguishine[3]—they sent them to a different type of jail.

When I saw other people being abused in the institution it’s even worse. You know it’s wrong and you’re there watching it, but you have no control. If you interrupt to try and stop it, you get even worse done to you. You see it all the time: people being abused around you. One time, I remember feeling so helpless (pauses) watching staff picking up a big handful of icy cold snow and holding a guy’s face right in it. They just smooshed his face right in the snow and held it there until he couldn’t breathe. They smothered him and yelled at him, “You do it my way or else.” I knew if I stood up, if I interrupted it would have been really bad for me. We learned to walk right on by because we didn’t want it to happen to us. They had a full system of social control. That’s how we lived. That was life in the institution. That’s part of the reason I want to fight for people’s rights everywhere I go now. I have to.

Getting out. It was strange when, after 18 years, one day without explanation or warning, I was tapped on the shoulder by a staff at 12 noon. Out of the blue they told me that at 12:30 I was leaving for Ingersol group home. And that was with only two pairs of institutional clothes, a pair of shoes and a hat. You put all that stuff in a banana box. Just like that, I walked out the door. I still don’t know to this day why they decided to let me go. Maybe it was because I was such a rebel the whole time I was in there they finally couldn’t stand it anymore.

Made me want to be an activist. It was time to turn all that horrible stuff into activism. The way it started was I met David Baker, a rights lawyer at ARCH Disability Law Centre, and started getting active. I was getting ready to start up People First of Ontario. People at the Association I was at attempted to stop me from starting up People First in Ontario. May 1978 was the first People First in Brantford meeting. It felt good seeing people coming together to talk about their rights. I knew I was on the right track.

I remember when the idea first came to me: I was really inspired by a magazine article about self-advocacy while I was in the institution. My dad sent me this magazine that got me going. I would read anything I could get my hands on in there—which wasn’t much. Reading about self-advocacy opened my eyes, and I wanted to get involved. I didn’t want anyone to be stripped of their rights again the way I had been in the institution (Hutton et. al., 2011). Once I got started with People First, it took off. I had a chance to talk to large groups of people about their rights all over the world. People First had me travelling the globe doing rights work. It was so important to me to keep going and spreading the message that you don’t have to live with abuse.

I initially was lied to going into the institution. People in power lied to me—bold faced lies that I would be able to get out anytime. That was really what made me want to be an activist and go the route that I have taken. I don’t believe anyone should be lied to. It’s unjust, no matter who you are. When you think about it, in advocacy, you have to be able to take a blow but not let it affect you personally. I took so many blows in the institution and lived to tell the tale. I was more than ready to be an activist.

I ended up doing all kinds of things with People First. I’m proud to say I worked on the name change at Community Living too. This was back in the 1980s when agencies were called “Associations for the Mentally Retarded”—which made you feel knee high to a grasshopper. People First members across the country wanted the name to change. There were a lot of politics—but we did it. It took a few years and storming out of meetings, but we did it. Real change comes slow. People First wanted a name that was non-labelling. We wanted to live in the community and with our peers, not locked away. We proposed the name “Community Living” and it was finally agreed on in 1985. That was at least a step in the right direction.

I also worked on an advisory committee on a case called the Eve case—that went right up to the Supreme Court.[4] A woman by the name of Eve (not her real name) was going to be sterilized—her mother wanted to have her sterilized and she didn’t want to be. People First got involved, and we ended up in the Supreme Court and won. That was the first time that people labelled with an intellectual disability won at the Supreme Court—speaking for ourselves.

Now I’m working with Respecting Rights at ARCH. It’s important to do social justice work in a neutral space. People First always controlled their agenda, you can’t have agencies controlling agendas. I co-founded Respecting Rights, which is a province-wide group—we are self-advocates, lawyers and advocacy staff working for change. With Respecting Rights, we do rights education for self-advocates, agencies and families all over the province. I thought it was important to have the word “respect” in the name of our group, because that’s what’s been missing. Working with the lawyers gives it an extra push.

Today’s self-advocacy. With a lot of self-advocacy groups today, I don’t see them tackling big issues. Back then, there was the Eve case—going right up to the Supreme Court of Canada to change the laws for people with disabilities. People don’t seem to work on these big issues today. It’s like self-advocacy is being controlled by agencies still. I don’t mind making waves. I think in many areas the associations are setting up what I call “social” advocacy committees that are taking away from People First. The advocates get treated to going to conferences. People First doesn’t have the money to send people to conferences. So self-advocates are being played. Their voices aren’t taken seriously.

People are still in the same crappy situation—but just not in institutions. ODSP[5] is still crappy. The Ministry says they are doing something about it. They say they raise the rates 10 cents a year. People living in the community don’t want to speak out about this crappy situation. They think if they speak out that they’ll get cut off. People are accepting of how bad things are. We need to keep challenging the system, not accepting it.

Martin’s Story

Background. Martin was placed as a young child in the Huronia Regional Centre (HRC). Originally opened in 1876 as The Ontario Asylum for Idiots, HRC is Ontario’s oldest institution. At the time, intellectual disability was seen as a medical condition and parents were often encouraged by health care professionals to put their children in institutions for care. Joffe (2010) has documented extensive physical and sexual abuse, regular violations of rights, and inhumane overcrowding. Martin’s account of surviving Huronia joins the thousands of others who experienced the same appalling treatment.

In Martin’s words. I spent 15 years in Orillia first, at Huronia. Then I got transferred to Pine Ridge institution in Aurora and spent five years there. This all started with my family. It was my mother mostly—she didn’t have the patience because of my disability. I never felt respected. I was being put down as being retarded. I remember being at my barber’s, and he said, “Don’t worry. Things are going to get better for you Martin, things are going to get better.” Then, when I was eight or nine, I was put in the institution. My mother didn’t even take me—she got my uncle to take me. I remember crying the whole way there in the front seat of the car. He said it was only temporary. I just cried. Well, it was apparently going to take a long, long, long time for things to get better.

I remember when it all started. My parents started fighting because they were having a hard time with me. First I was having trouble in school, then they lost me one day in the city. They really started fighting. My mother said, “You need a psychiatrist! You need to be put away! We can’t look after you!”

Then my mother took me to five psychologists—one after the other. My mom made up stories, telling them I sleepwalked on the roof, got in fights at school, getting car rides from strangers, and that I hit them. Then a psychologist said they thought I needed an institution where I could learn to calm down. They said I needed to be put away for at least 20 years or more. The fifth psychologist agreed, “He needs to be put away—no doubt about it. He doesn’t belong in society.” I remember that.

Of course, I didn’t have a voice in any of this—I wasn’t allowed to speak. They wouldn’t hear me out. I ended up locked up in Orillia for 15 years. I remember the day I was taken there when I was nine years old. I asked, “Am I going to be allowed to come back home?” They made me believe that I was only going to be in there a short while—that it was only temporary. I just wanted to know I could come out. I was just a kid. That turned into 20 years of my life— gone.

It was bad at Huronia. They made us do back-breaking work all the time. They’d hit us if we didn’t do it right. There were fights between the guys who lived there a lot.

The staff punished us all the time. I remember there was a big block of wood with a steel handle that we were forced to push up and down the floor over and over. They made us do this for hours and hours. If you stopped, the staff would come up behind and push the thing hard into your gut. I had to stop one time—I just couldn’t keep doing it over and over like that. The staff pushed the steel handle really hard and painful right into my gut. I was doubled up in pain. It wasn’t fair. I was just a kid, being tortured like this.

I used to say, “Where did you get the right to do this kind of torture to people with disabilities? You’re supposed to be giving support and protection to these people, not beating them up and punishing them.” I wanted to advocate for myself and the others in there. I knew I had to start advocating, otherwise things were just going to keep getting worse.

When it came to the fifteenth year, they were going to be transferring me to Pine Ridge[6] in Aurora. I was told, “This is the last day. You will get your stuff packed and you’re going to Pine Ridge tomorrow.” Just like that, no advance warning or preparation. One day’s notice I was given after all of that. I didn’t know what Pine Ridge was going to be like.

But it didn’t get better. It got worse—it was worse in different ways than Huronia. Pine Ridge was really bad. I had the crap punched out of me at Pine Ridge.

The water torture. If you didn’t do what you were told at Pine Ridge, you got the water torture. They put you in a freezing cold shower, put a bar on the door and you have to sleep shivering on the cold hard floor.

They stripped me—took all my clothes off. They laid you down on a stretcher, tied your body down tight across your chest so you couldn’t move, and tight across your legs. Then they rolled you down the hall with you all tied down. They’d take you right into the shower. Then, while you’re all tied down not able to move or get away, you’d suddenly have the freezing cold water coming down on you. You were freezing and couldn’t move cold and naked, soaking wet, and restrained down on the bed. They would yell, “What do you think of this now! Do you want to apologize to us now!” After that, then they put you in the side room in isolation. They leave you there just shivering. Everyone could look through the window at you all naked lying on the floor. You didn’t even get fed when you were in the side room like that. That’s what they did to you there.

When you would work at Pine Ridge, they said if I ever talked back, they said “You’ll see what you’ll get from me!” They always threatened us. I used to talk back because I knew it wasn’t right. I used to watch them hitting the residents there all the time. If residents were acting up, they would just go and punch the crap out of them. They said it was the only way they could get them to calm down.

One day a staff came in drunk. He was slurring—I could see he was drunk by the way he was talking and everything. The head supervisor was the same way. He was angry and he grabbed me. He had me undressed and put me in the side room. It wasn’t good. Some things I just don’t talk about too much. I think I’ll stop that part there (pauses) that’s enough for now (pauses).

In Huronia they did the beating up. In Pine Ridge they did the torture with the cold water and side room and everything else. The attitude was, “You’re going to learn that we are in charge of you. When we want something done, you’ll do it if you know what’s good for you.” There was only one or two staff I ever trusted in all those years. One of the staff, he came in the night and took me out. We went down to play cards. He let me have a coffee with him. Only staff I trusted in all those years.

Family. My family came to see me once a month. I told them the bad things that were going on, and they said the staff told them I wasn’t behaving. They said, “if you behaved yourself, none of that would happen.” They took me out to eat, out for lunch. They made up stories like, “we can’t have you home anymore.” I couldn’t trust anybody. Families can be hard too. Finally, I did get out—it took a long, long time, but I did. I met with the head supervisor and the social worker. I remember the day I got out: they were even making jokes about it. I got taken over to the foster parent’s house in Thornhill. My social worker introduced me to them. I was going to live downstairs in the basement with some other people with disabilities. Finally I got out.

Advocacy work. I was in the Reena foundation[7] and everyone was talking about people being treated so badly. People with disabilities wanted to be seen and heard. Then Peter Park and Pat Worth came out, and then all of a sudden they asked if I would be interested in being involved in People First. We paid $5 for membership. People First was all about listening. We all talked about what we wanted in life.

A lot of our people always felt, why aren’t people with disabilities getting to do what they want? With People First, I would ask people with disabilities, “Do you like the way staff are treating you?” People kept saying “I want to be able to speak out!”

I advised people to go tell their staff what they wanted. You are supposed to be telling the staff what you want. People have the right to have a voice. I would speak to my worker and tell them what’s bothering me.

At Pine Ridge we weren’t allowed to ask for what we wanted. So we had to learn how to stand up for ourselves. That was advocacy for us. At the time of the institution, we didn’t have the right to anything. We had to do what the staff wanted us to do—otherwise we would lose our privileges. “Who the heck do you think you are! Did I tell you that you have the right to come to me!” They would say if I asked for anything—if I stood up for myself. Then you would get the water torture again.

Once people got out of the institution, then they saw what we could learn and everything else. No matter what, it was a struggle. After I got out, I started to feel I was a part of everything.

I was offered a chance to show what I was capable of. I got a job at Metro Ambulance Services. It felt good. In 1993, I met Shelley, my wife, at a People First meeting. In 1994, I wanted to give her a ring. But both our families didn’t want that to happen. As soon as I heard Shelley speak up her part, I knew I could do it too. She inspired me the way she spoke up for herself.

Eventually our parents did come to the wedding. The wedding was at the Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto. Shelley wore a white dress and I wore a black tux—and with a white bow tie and everything else—really, really dressed up. Now we’re going to celebrate 19 years of marriage. We had to stand up to my mother to get married. She wasn’t going to let us. Now, here we are 19 years later.

Self-Advocacy from the Ashes

Institutional Abuse. Peter and Martin’s narratives, and the depicted images based on their stories, highlight the common themes of forced institutionalization, disempowerment, abuse, and isolation from society and family. They are not alone in their stories. We know that persons with disabilities experience abuse more frequently than the general population (Reiter, Bryen, & Shachar, 2007; Sobsey, 1994). However, abuse continues to remain largely invisible as persons with intellectual disabilities often reside in isolated settings where they are often dependent on others for support. Although abuse that has occurred within institutional settings has been researched (Broderick, 2011; Chupik & Wright, 2006; Stewart & Russell, 2001), there remains a stark lack of knowledge regarding the context of institutionalization of persons labelled with intellectual disabilities in Ontario (Rossiter & Clarkson, 2013). Stories like those of Martin and Peter help to uncover these abuses and serve as an important voice in empowering survivors to contribute to the scholarship of institutionalization and institutional abuse.

Self-Advocacy. Despite the horrors that Peter and Martin faced, their stories highlight the importance of self-advocacy in promoting the healing process and in giving survivors control over the narrative of their own experiences and empowerment in preventing future abuses. For example, Peter talks about being denied the right to be educated about what was going on in the world. His words speak to the outright removal of basic rights and freedoms that he and all those institutionalized experienced. These losses of freedom that he experienced laid the groundwork for his future commitment to advocacy —to never wanting others to have their rights denied as he did. Similarly, Martin talks about the pain of being denied the ability to ask for what he wanted when he was at Pine Ridge. For Martin, advocacy is about being able to stand up for himself and demand that his needs get met.

In Canada, the self-advocacy movement can be traced back to 1973 when the People First movement began. People First of Canada is a national organization made up of self-advocates who work to give a voice to people labelled with an intellectual disability (People First, n.d.). There are many People First chapters across Canada that are working to tackle issues such as human rights and citizenship rights. The People First chapter in Ontario was formed in 1982 with Peter Park as Co-founder.

Self-advocacy groups are being promoted in large urban areas such as Toronto (McKhail, 2010), but much work needs to be done across the country. People with intellectual disabilities continue to have their rights violated on a regular basis and are not treated as equal citizens (Hutton et al., 2011). There continues to be a lack of respect for people with intellectual disabilities within Ontario, including within the developmental service sector (Hutton et al., 2011). As evidenced by Martin and Peter’s stories, institutional survivors greatly benefit from self-advocacy groups as it is a place where their voices are being heard and validated, and it provides a vehicle for social change.

Moving Forward: Empowerment not Apologies. On December 9, 2013, the Ontario government officially acknowledged the institutional abuses that occurred in Ontario at the Huronia Regional Centre and other institutions when the Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne delivered an apology speech to the Ontario Legislature, and to thousands of survivors. While grateful for the voice of Kathleen Wynne, Peter reflects on the need for the government to go beyond apologies:

Although it was wonderful to hear the government’s political apology, that does not make up for all those years we suffered at the hands of others…I personally felt the premier’s apology about the institution was almost a staged statement written by a politician to make the premier look good. When you look at the crappy settlements people are getting—$2000 for years and years of horrific abuse—people have to start challenging things like that and not accepting it. I have no trust in the government. How could I after what I’ve seen?

Martin adds:

Even though I received $2000 from the Huronia settlement, I still feel that it is not enough to apologize for the harm done. Why are we still experiencing pain and harm? $2000 will not make up for the pain of one day let alone a lifetime of harm. The system of payment was unfair and was not accessible for people with intellectual disabilities.

In reflecting on the work that needs to be done, Martin and Peter stress the need for those without disabilities to honour the lives and the voices of those who survived institutionalization, and to continue to improve the world for people labelled with intellectual disabilities living in the community today. As stated by Griffiths et al. (2003), although recent decades have shown a shift toward the respect for the rights of persons with disabilities, there are still rights restrictions in today’s system that need to change.

In the words of Peter and Martin:

There is still a lot that needs to change in today’s self-advocacy, such as agencies still trying to control what we say. Advocacy should be started in more places and there is the need to get the word out to help people to advocate for themselves. We’ve got to show society that things can be different. We want to show people what advocacy should be like.

References

- Bazar, J. L. (2015). Establishing “Oak Ridge.” In J. L. Bazar (Ed.), Remembering Oak Ridge Digital Archive and Exhibit.

- Broderick, R. (2011). Empty Hallways, Unheard Voices: The Deinstitutionalization Narratives of Staff and Residents at the Huronia Regional Centre. Unpublished major research paper, York University, Toronto, Ontario.

- Canadian Pharmacists Association. (2013). Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties (48th ed.). Ottawa: Author.

- Charlton, J. (1998). Nothing About Us without Us. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Chupik, J., & Wright, D. (2006). Treating the ‘idiot’ child in early 20th century Ontario. Disability & Society, 21(1), 77-90.

- Coons, K. D., & Watson, S. L. (2013). Conducting research with individuals who have intellectual disabilities: Ethical and practical implications for qualitative research. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 19(2), 14-24.

- E v Eve, [1986] 2 SCR 388.

- Griffiths, D. M., Owen, F., Gosse, L., Stoner, K., Tardif, C. Y., Watson, S., Sales, C., & Vyrostko, B. (2003). Human rights and persons with intellectual disabilities: An action-research approach for community-based organizational self-evaluation. Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 10(2), 25-42.

- Horner‐Johnson, W., & Bailey, D. (2013). Assessing understanding and obtaining consent from adults with intellectual disabilities for a health promotion study. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 10(3), 260-265.

- Hutton, S., Park, P., Park, R., & Rider, K. (2011) Rights, respect and tokenism: Challenges in self-advocacy. Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 16(1), 109-113.

- Joffe, K. (2010) Enforcing the rights of people with disabilities in Ontario’s developmental services system. In The Law as it Affects Persons with Disabilities. Ottawa: Law Commission of Ontario.

- Johnson, K., Minogue, G., & Hopklins, R. (2014). Inclusive research: Making a difference to policy and legislation. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(1), 76-84.

- Kidney, C. A., & McDonald, K. E. (2014). A toolkit for accessible and respectful engagement in research. Disability & Society, 29(7), 1013-1030.

- Lemay, R. A. (2009). Deinstitutionalization of people with developmental disabilities: A review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 28(1), 181-194.

- Marlin, B. (2010, July 28). Judge certifies $1-billion class-action suit over Huronia institution. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/judge-certifies-1-billion-class-action-suit-over-huronia-institution/article1387937/

- McKhail, S. (2010). Self Advocacy: What is a Self Advocate? Retrieved from http://www.griffin-centre.org/rOUT_serv_intdis_seladv.php

- McKim, C. (2009, March 18). HRC was a nightmare for some. The Orillia Packet and Times. Retrieved from http://www.orilliapacket.com/2009/03/18/hrc-was-a-nightmare-for-some

- Ministry of Community and Social Services. (2012a). History of Development Services: The First Institution. Retrieved from http://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/dshistory/firstInstitution/

- Ministry of Community and Social Services (2012b). Oxford Regional Centre. Retrieved from http://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/dshistory/firstInstitution/oxford.aspx

- Ministry of Community and Social Services (2014). History of the Huronia Regional Centre. Retrieved from http://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/mcss/programs/developmental/HRC_history.aspx

- People First of Canada. (n.d.). People First of Ontario. Retrieved from

- http://www.peoplefirstontario.com/about/

- Porter, R. S., & Kaplan, J. L. (2011). The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Whitehouse Station: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.

- Reiter, S., Bryen, D. N., & Shachar, I. (2007). Adolescents with intellectual disabilities as victims of abuse. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 11(4), 371-387.

- Rossiter, K., & Clarkson, A. (2013). Opening Ontario’s “saddest chapter:” A social history of the Huronia Regional Centre. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 2(3), 1-30.

- Seth, P., Slark, M., Boulanger, J., & Dolmage, L. (2015). Survivors and sisters talk about the Huronia class action lawsuit, control, and the kind of support we want. Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 21(2), 60-68.

- Sobsey, D. (1994). Violence and Abuse in the Lives of People with Disabilities. Baltimore: Brookes.

- Springgay, S., Irwin, R. L., & Kind, S. W. (2005). A/r/tography as living inquiry through art and text. Qualitative inquiry, 11(6), 897-912.

- Stewart, J., & Russell, M. (2001). Disablement, prison, and historical segregation. Monthly Review, 53(3), 61-75.

-

The Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties (CPS) is a widely used Canadian pharmaceutical reference guide (Canadian Pharmacist’s Association, 2013). ↑

-

The Merck Manual is a medical reference book, published and updated regularly by the American pharmaceutical company Merck & Co. (Porter & Kaplan, 2011). ↑

-

Penetanguishine is a psychiatric institution intended to provide custodial care to the “criminally insane.” It originally opened in 1904 as the Asylum for the Insane, Penetanguishene. Over the years the practices have changed, but it has been in continuous operation. It is now known as Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care (Bazar, 2015). ↑

-

Referenced here is E v Eve, [1986] 2 SCR 388. ↑

-

The Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) is a monthly financial support program for eligible Ontarians living with disabilities. It provides for basic needs like food, clothing, and shelter. There are ongoing advocacy initiatives to increase the rates. ↑

-

Ontario opened Pine Ridge Centre in Aurora, as an institution for people labelled with developmental disabilities to ease the increasing capacity at the Huronia Regional Centre in Orillia.

↑ -

Reena is an agency in Toronto providing residential and recreational services for people labelled with intellectual disabilities. It was first was established in 1973 by parents of children with developmental disabilities as an alternative to institutions. ↑