Unheard Voices: Sisters Share about Institutionalization

Madeline Burghardt

York University

Victoria Freeman

York University

Marilyn Dolmage

Colleen Orrick

Loyalist College

Abstract

The recent emergence of institutional survivors’ accounts of mistreatment and abuse in Ontario’s institutions for the “feebleminded” offers a window into Canada’s long history of segregation, mistreatment, and neglect of people labelled intellectually disabled. The breaking of this silence has also allowed the stories of others who were deeply affected by institutionalization to come forward. Narratives from siblings of institutionalized individuals, although not first-hand accounts of the life inside institutional walls, offer much needed perspective on the extensive and ongoing effect of institutionalization in the lives of thousands of families, and offer additional insight from another marginalized group that until now has not held a place in Canada’s visible and spoken history.

This paper is a weaving together of three sibling narratives that were part of a panel at the Canadian Disability Studies Association (CDSA) conference in Ottawa, Ontario in June 2015. All sisters of institutionalized persons, the three contributors remark in particular on their profound experiences of loss after their brother or sister was sent away from the family home. The contributors believe that it is through the sharing of such experiences that society can better come to understand the devastation wreaked upon both individuals and families through misinformed and prejudicial policies over a period of more than 150 years.

Keywords

- Institutionalization

- siblings

- family

- loss

- fragmentation

- advocacy

Unheard Voices: Sisters Share about Institutionalization

Madeline Burghardt

York University

Victoria Freeman

York University

Marilyn Dolmage

Colleen Orrick

Loyalist College

The recent emergence of institutional survivors’ accounts of mistreatment and abuse in Ontario’s institutions for the “feebleminded” offers a window into Canada’s long history of segregation, mistreatment and neglect of people labelled intellectually disabled. Canada’s first “Asylum for Idiots” (sic) was established in 1876 on the shores of Lake Simcoe near Orillia, Ontario, and was initially considered a progressive development from earlier asylums due to its designation as a facility solely for the “feebleminded.” Over the next 150 years, Canada’s institutional system expanded significantly,[1] reaching its peak in the post-World War II years when the internal population of the Orillia asylum alone reached almost 3,000 residents.[2] By the time the last of Ontario’s institutions finally closed their doors in March 2009, many thousands of people had been sent to live there, some as young children, and many never returned to life in the community.

In addition to valuable scholarly contributions about the geopolitical history of institutions in Canada (e.g. McLaren, 1990; Radford, 1991; Radford & Park, 1993; Simmons, 1982) and Malacrida’s (2015) more recent work detailing the history and conditions inside the Michener Institute in Alberta, the stories of institutional survivors have begun to gain a stronger presence in mainstream Canadian life. Emerging from decades of silence during which the public heard nothing of the situation at Ontario facilities save for a few isolated revelations from prominent Canadian politicians and writers (e.g. Berton, 2013, originally written in 1960; Williston, 1971), the stories of institutional survivors as revealed through such projects as Remember Every Name, Recounting Huronia and Surviving Huronia,[3] along with the class action lawsuits brought against the Ontario government and the media attention they have garnered,[4] have raised consciousness on the lived experiences of institutionalization. This breaking open of the story has positioned survivor narratives as a central point from which, it is hoped, greater understanding and further changes in public perceptions and policy might emerge.

Narratives from siblings of people who were institutionalized due to intellectual disability offer insight into the impact of institutionalization on and within the family, including its effects on family relationships and understandings of disability. In the three narratives presented below, three sisters of institutionalized persons provide an intimate perspective on the extensive and ongoing effect of institutionalization in their lives, and by extension, in the lives of thousands of families, thus adding to the growing canon of Canadian disability history.

This paper presents narratives from three siblings who were part of a panel at the Canadian Disability Studies Association (CDSA) conference in Ottawa, Ontario in June, 2015 (Dolmage, 2015; Freeman, 2015; Orrick, 2015). The three contributors remark in particular upon their profound experiences of loss after their brother or sister was sent away from the family home. Although a painful process, all of the contributors believe that it is through the sharing of such experiences that society can better come to understand the devastation wreaked through misinformed and prejudicial policies.

Colleen: Valuing Gerry: Lessons from my Brother

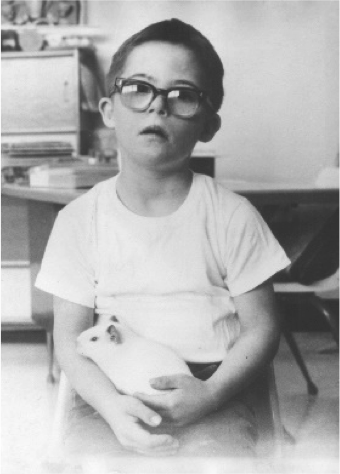

I want to tell three stories about my brother, Gerard, that I hope illustrate themes about the institutionalization of a sibling (Figure 1). My brother Gerard was born on September 27, 1957; he died on April 19, 2009.

Gerry moves away: Breaking the bonds. One night when I was ten years old, while my mother was tucking me in for the night, she told me that my youngest brother, Gerardie, who was five years old, would be going away to school. I asked her if he was going to boarding school and she said it was a kind of boarding school. I was a voracious reader, and with my head full of romantic notions about boarding school gleaned from novels, I immediately asked if I could go too. She said no, it was only for children like Gerard.

I don’t remember the day he left. I have wracked my brain trying to see if I could recall even a snippet but I don’t.

My parents were both involved in the local Association for Retarded Children (sic), as it was then called. We knew other families who had children with developmental disabilities. Some lived at home and some were away. So it wasn’t completely foreign that a sibling with Down syndrome might have to move away.

My parents worked hard to keep our family connected. Gerard was home some weekends and holidays, for visits in the summer and over thanksgiving and Christmas, weddings and various family celebrations. We also took holidays near him at the institution. One of our favourite family holidays was at a beach on Lake Erie where my Dad rented us inner tubes to float around on. It was kid heaven! We stayed at hotels and ate in restaurants—rare treats.

My parents lobbied hard to get Gerard moved to a closer institution, and he did move some years later. This time we could go and get him and come home again all in one day. No more hotels and beach holidays. What I do remember from this time was that my parents bought sports equipment for Gerard and took it to the institution. He rode a bike in summer and played hockey and skied in winter, much like the other kids in our family.

At the same time, I remember going with my Dad and some members from the Association for the Mentally Retarded (sic) to the Huronia Hospital School in Orillia where the Association had adopted a ward. I remember the bleak ward and the men crowding around to get some of the gifts that had been brought for them. I never associated these horrible living conditions with the institution where my brother was living. We had been on a tour of Cedar Springs where Gerard lived; it was new and bright, and I remember huge floor to ceiling windows. I wonder now if my parents feared this as my brother’s future. They continued to lobby for him to live closer to home. And when he did finally move to an older but closer institution, my parents were strong advocates. But they could never let go of the belief that institutions were the best place for Gerard.

As an adult, I can somewhat understand the excruciating decision my parents had to make in relinquishing their five-year-old to an institution. They did what they thought was best for him and they clung to that belief for the rest of his life. I do know that my mother never recovered from having to give him up. My aunt once told me of a time when she and my uncle had driven Gerard back to the institution to save my parents the trip. She said my mother told her, “Don’t watch them walk with him down that long hallway at the entrance; it will break your heart.”

I am not sure how long this period lasted once Gerard entered the institution. I think it was three months, a painful time for my parents. I don’t have clear memories of how those months affected us kids, but I do remember that when the ban was lifted there was a joyful reunion as we went to visit Gerard. Again, in hindsight, I believe my parents endured this because they believed it was the best thing for their child.

By the time I was in my teens my mother was clinically depressed and eventually hospitalized. I believe that relinquishing Gerard was a major factor in her depression. My other two brothers got into drugs in their teens, one to a very destructive degree that almost ended in his death. Was it because Gerard was institutionalized? I don’t know. It would be hard to list all the factors; it was the 60s/70s. But it would be naive to think that having to place Gerard in an institution played no role in these events. Me, I went to university.

“I only have two brothers”: Usurping the role of family. When I was in my teens, an incident occurred that has stayed with me. I was talking to a new acquaintance at the back door of our home. I mentioned that I had two brothers, leaving Gerard out of the count. Once the acquaintances had left, my mother confronted me and asked me if I was ashamed of Gerard. I responded that no, of course I wasn’t ashamed, only really tired of having to explain. Looking back, I see that by this point I had the sense that our family was different in a significant way. However, many people knew I had three brothers and had met Gerard, as he was home frequently, went places with our family and was well known in our neighbourhood. So I don’t think my omission was a cover up; I just did not want to have to explain the situation to another new person—it felt like too much private information to share so soon.

At some point, someone at the institution changed Gerard’s name to Gerry. At the time and to this day, I feel that this was a violation. We had always called him Gerardie. Now suddenly it was Gerry. And our family did adopt the name. At first I remember resisting it. But whenever there was contact with the institution, if you didn’t call him Gerry, they didn’t know who you were talking about. My parents encouraged us to adopt the new name after a while so that there was no confusion for Gerard. As a child or teen, I don’t think I conceptualized this notion that the institution had usurped the function of family in many ways, including the highly personal area of naming one’s child. I think for me this was the first realization that things were amiss in a serious way.

“Get him to a hospital”: Balancing advocacy and protection. Once I had graduated from university, my first job was in a small institution for children with developmental disabilities. I still don’t remember associating the conditions there with my brother’s living conditions. But I did start to grow and learn about devaluation. I lobbied hard to prevent a young woman from being sterilized, only to go on vacation and return to find the deed had been done. I learned about institutionalized support versus human support, although I didn’t call it that at the time. I learned a lot about how children could be treated by support workers in an institutional setting. But I never made the leap to how Gerry might have been treated. I opted to treat the children in my care as children, children who someone loved, and not as cast offs.

In the early 1990s, my mother called me and told me that Gerry had suddenly refused to go into bathrooms at the institution and hadn’t urinated for three days. I replied that she should make them take him to a hospital or he would harm his kidneys. I’m not sure that he was taken to a hospital and I have cause to think that there might have been reasons the institution wanted to avoid that. Gerry became very paranoid. He wouldn’t let anyone touch him. He refused to either groom himself or let anyone else groom him. They started knocking him out so they could shave him, clean his teeth, and trim his nails. He started refusing to consume anything he suspected might have medication in it. I secretly cheered him in that; I think it was a very smart thing for him to do under the circumstances.

At the time, I attended a workshop with Herb Lovett and I asked him about Gerry’s behaviour and my suspicion that Gerry had been assaulted in a bathroom at the institution. He confirmed that it was a reasonable conclusion to make. I voiced my suspicions to my mother. She was horrified and refused to talk about it. It took her two years to finally tell me that I might have been right. Meanwhile, I went and spoke to Orville Endicott, the lawyer for Community Living Ontario. He advised me that unless we had some kind of evidence other than his behaviour, it would not get anywhere in court. We had no other evidence.

My mother went to the institution and demanded that Gerry be seen by a doctor outside the institution. It was a doctor she knew from her days in the Association for Retarded Children (sic). He diagnosed a reactive psychosis and prescribed medication. Gerry had symptoms of the psychosis for the rest of his life.

At this point, I realized that my understanding of Gerry’s life was radically different from that of my family. I realized that I had to balance fighting for him with protecting my parents. As the other contributors on this panel will attest, this is hard, very hard. My mother once asked me what I thought of a family home that Gerry was living in and I told her I didn’t like it and listed the reasons why. She was mad at me. Sometime later, I was unhappily proved right. When the class action lawsuit for Southwestern Regional was launched, I made sure that Gerry’s name was on the list of people in the class. I had to speak to my father about it. He never believed Gerry was harmed. Gerry died in 2009 and so any money in a settlement would do him no good. My father declined pursuing a settlement.

When Gerry was 51, he fell down some stairs at a family home he was living in. He had a massive brain injury and was put on life support. I believe that he had a massive brain bleed first and then fell down the stairs. There was no bruising or external evidence of injury, but the imaging evidence was devastating. A few days later, I sat with him as life support was disconnected. My dad and my brothers said they didn’t think they could be there. My father was weeping in the waiting room with my aunt. I stayed. The last thing Gerry felt was my kisses on his arm. The last thing he heard was me telling him I loved him. Immediately upon leaving the room after Gerry’s death, the coroner asked to speak to me about what he felt was evidence of sexual assault. I knew that all those years ago, what could not be proven at the time, was now evident. I never told my Dad.

Our family has been robbed of so many things. Gerry was robbed most of all: he was robbed of the protection of his family. Even knowing he had come to great harm, the best I could do for him was to say, I think I know what happened to you and I’m sorry it happened. Our family was robbed of him and he of us. Through the tenacity of my parents we managed to stay connected, but I never knew him as I knew my other brothers. There are huge parts of his story that I don’t know and will never know. I do know that we loved each other very much. We had similar interests and likes (including a love of rabbits!) and I am grateful to know them. He had a wonderful sense of humour, and even in the years when he was suffering from mental illness, that sense of humour would shine through. He loved most animals and they sensed his gentle nature and responded to him. He loved books and writing—another thing we share. I am grateful to know about the things we share, and I am grateful to have been his sister.

Marilyn Missing Robert: Inspiration for Advocacy and Class Action

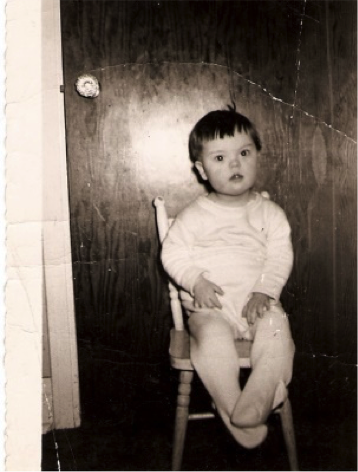

I was four years old and felt very excited that my mother was having a baby. I remember getting the pink and the blue woolen baby blankets out of the cedar chest—like this folded blue blanket, edged with satin binding. Sewn on it is a label that says Kenwood Wool Products (Figure 2).

My older brother and I had talked about baby names. So when I heard we had a boy, I immediately called him Robert Bruce. Then they told me he was “born wrong.” He was not coming home. All those baby things had to be put away before my mother got home from the hospital. I don’t remember doing that, but I have a very clear memory of my mother coming through the door. I was so glad to see her. I ran down the stairs and blurted out “Where is the baby?” Then it seemed as if all hell broke loose. It was awful to see my mother weep like that; she fell apart.

I had made my mother cry. It was all my fault. I’d been told not to ask questions. Right in that moment, I learned that it was my job to protect my mother by not talking about this. I learned her feelings were more important than mine. When I asked “Where’s the baby?”, I knew he wasn’t coming home. I probably just wanted to know where he was! I had planned to take care of him. Who was doing that now? If anyone knew, they didn’t tell me.

I had lost “my” baby, but I realize now that I also lost my parents. We were all lost; my family was incomplete and unstable. Somehow, I came to believe that Robert had died. What I felt was much more complex than grief. In my house, we all lived with absence—not even ever knowing this missing person. There were no words, no photographs…just nothing.

Soon after he was born, at Christmas, I got a blue doll buggy, fitted out with a blue woolen blanket. My mother had cut Robert’s blanket apart. She bound the rough edges of the fragment carefully with satin. I walked my doll in that buggy all around the neighbourhood. I was like a little mother. What must the neighbours have thought? I felt responsible for keeping Robert a secret from the world around me. I just recently realized that in fact many people—especially those neighbours who saw me pushing my little doll buggy—must have known more about him than I did.

It was the 1950s—idealizing perfect families, haunted by eugenics. Having a child “born wrong” meant our family was tainted; my own future—genetically—was too. Would they abandon me if something went “wrong” with me? The doctor told my parents that keeping Robert would ruin my life; in effect, he was sacrificed for me. Later, I kept the secret because I felt increasing shame about my parents abandoning a vulnerable child. After I was a mother, it was years before I could tell my own children. So I had abandoned him too.

At some point, my older brother told me Robert had not died, but was alive in an institution. I found a letter from the Ontario Hospital School, Orillia. Visiting Orillia once, I looked up the institution number in the phone book. I tried to imagine that place, but I could not imagine Robert.

Robert died when I was 13. That’s the only time I ever saw him: in a casket, dead. He was very thin and small for an 8-year-old, apparently wearing the size three clothes my parents sent when he was admitted to Orillia five years earlier. I remember his sweet face, but all I saw then was Down syndrome.

We had a funeral, and some secrets were finally revealed. I discovered that Robert had lived near us in Hamilton for his first three years. My grandfather had paid someone to look after him. He had visited; he even drove Robert to Orillia when he was admitted. I felt outraged that my grandfather knew Robert—alive—and I did not.

I have spent many years trying to “find” Robert since he died, trying to get closer to him. I got a summer job at another Ontario institution. I found Colleen’s brother Gerry there. I apologize if I stared when you visited, Colleen. I wanted to know what made your family different from mine, what kept you involved. I knew how much families needed help. That’s how I ended up doing social work at the institution where Robert died. In my five years at what is now called Huronia Regional Centre, my work involved connecting with families, assisting people to move out and supporting people in the community.

I left to have my own family and, as fate would have it, our first child, Matthew, was born with medical problems resulting in disabilities. We struggled to ensure our three children attended school together, and to assist Matthew to have the education, medical treatment, employment, and community life he wanted. Alongside disabled people and their families and allies, I continue to fight segregation and work for effective inclusion, promoting direct funding, supporting families, and changing schools, so students of all abilities learn better together.

Tragically, Matthew died in 2004 at the age of 29. We try to pass along to others what he taught us.

My husband and I have assisted Marie Slark and Patricia Seth in the class action concerning neglect and abuse at Huronia Regional Centre. This led to a settlement and an apology from the Ontario government in 2013. It continues to be a tortuous process, and claimants are still waiting for their small payments. Worse yet, it appears that those with greater cognitive and communication challenges have been disadvantaged by the claims process. However, we have had access to institution files and government documents. People who can speak for themselves are finally believed. We can unravel what happened to those who died and better understand people who do not communicate with words. I felt that the class action finally announced Robert’s birth and mourned his death, and respected what he had endured in the few years in between.

I had always remembered Robert’s birthday. One year on that very day, I got to thinking that he probably had rough, dry skin and that no one would ever have given him a gentle bath and applied soothing lotion. I missed him to my very fingertips. But my loss was nothing compared to Robert’s. No one had ever touched him out of love. The really important story of separation is not mine, but Robert’s.

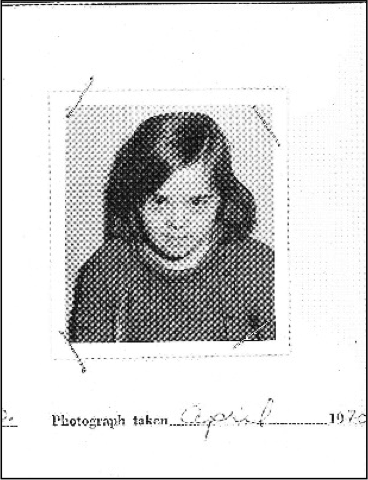

The government lied to my parents about this “hospital school.” Robert never attended school; he spent five years in a crib. The Ministry of Health ran the place, but he suffered from hepatitis, salmonella, and many other infections. His five years there were written in lab tests and a few brief notes: “lies in bed on stomach and wiggles about;” “can tie himself in a ball.” Sometimes they wrote that he was “quiet and gives little trouble;” later, “destructive and tears his clothes.” You see his picture just before admission. Two months later, the institution called him “obese.” After five years, he had gained only eight pounds and they called him “well-developed.” They fed him C.F.M., or Complete Food Mix—a tasteless powdered mixture. I am so upset that he experienced no flavours.

It was only when I got his file that I found out my brother was never “Robert Bruce.” My parents just dropped that middle name altogether, which was my father’s name.

Last year, we met a man who was a summer student in that institution in about 1990. Staff taught him to assert control in a crowded ward—but avoid responsibility—by slamming doors into residents. But they warned him to hurt only those who had no family contact.

Robert was denied humanity. He experienced inhumanity. He was just “one of them.” He was put “over there.” Whenever that happens, people are harmed. I have talked too much about how I missed Robert. Because Robert missed everything: flavours, sunshine on his face, music, toys, movement, snow, plants and animals, love, a future.

These stories seize power away from those who hid behind the secrets. That is why the people who were harmed must guide the research and lead the advocacy.

Martha Matters: Victoria Surviving Family Trauma

Many people now recognize that people who were institutionalized for years or even decades because of intellectual disability are survivors of a misguided form of incarceration and treatment that severely limited their development and the full enjoyment of their lives. What is less well known is that institutionalization also affected other family members, and specifically siblings. In my case, my sister Martha’s institutionalization from the age of 20 months to age 15 irrevocably altered the dynamics of my family and left me deeply traumatized in ways I have only unraveled decades later. I have come to recognize that in some sense I am also a survivor, for my own development as a person was severely derailed by what happened to my sister.

I am a historian of Indigenous-settler relations in Canada and a multidisciplinary artist. My section entails excerpts from a book-length unpublished manuscript entitled Welcome: A Memoir, which explores how, although born into white middle-class privilege in the late 1950s, both my sister and I were shaped and harmed by discourses about difference, one visible (my sister’s Down syndrome) and one invisible (my hidden gender fluidity and bisexuality). My reason for writing is to understand both of our lives, to honour my sister, and to heal from the pain of my loss of her through her institutionalization that has shaped my entire life.

It was only after my sister’s death in 2002 that I began to question the family narratives that had sustained our views of my sister and her institutionalization, and for the first time sought to understand who my sister really was and her relation to me. Accessing Martha’s institutional file, meeting institutional survivors and their families and allies through the class action lawsuits, and forming new relationships with people with Down syndrome has helped me heal and see the need for the siblings of those who were institutionalized to share our stories. As children we often could not speak of our loss, loyalty, and trauma, yet we witnessed and were sometimes implicated in our sibling’s dehumanization, to our great detriment. To illustrate the consequences, I offer you my experience. I also include several photographs that offer a visual shorthand for my sister’s experience and my own journey of healing.

My younger sister Martha was born with Down syndrome in 1958 and was institutionalized at the Rideau Regional Centre in Smiths Falls in 1960 when I was four years old. A photo from my sister’s institutional file (Figure 4) shows her two months after she was admitted, held in anonymous arms, looking up into the camera with a bewildered expression on her face. I cannot imagine what it was like for her to be removed from everything and everyone she knew at this extremely young age.

A photo of me, my mother, and my other sister, Kate (Figure 5), was also taken a few months after Martha was put in the institution; Kate was born just two weeks after Martha was taken away. In the close-up (Figure 6), you can see my clenched jaw and pursed lips; something is choked down, my body refusing to discharge its energy. My pudgy arms are those of a four-year-old, but my expression is of a much older child, all intensity and disillusionment and anger. I am looking out at the world and I don’t like what I see.

The house was brighter now, but after the initial celebrations of Kate’s birth, my own mood darkened. I was still bewildered and there was no place for my grief…My parents did not seem to recognize that I lived in a state of silent, impotent rage. No one seemed to recognize that my world had been taken away from me or that I felt I couldn’t trust anything. It felt wrong that Kate was nursed in the same rocking chair that Martha had been, and was changed at the same change table. My mother seemed to like this baby better than Martha, but I could not forgive this interloper for taking the place of my sister. And my father became completely wrapped up in Kate. Perhaps he poured all of his anguish about Martha into his love for this new child. Perhaps he turned away from me because he couldn’t face my bewilderment and pain.Even now, more than 50 years later, I can’t begin to express the rage I felt, the bitter sense of loss. I was never able to speak it then; I swallowed it down, was a good girl, denied my pain to lessen the pain of others. I did this out of love for my parents, but also out of fear, for if my parents did not love Martha, perhaps they also only pretended to love me. Perhaps one day I would also be sent away to some awful place. I had not just lost Martha, then; I had lost the security of my parents’ love.My rage didn’t change anything and over time it dissipated. Eventually my feelings about my sister were locked away in a private place that I shared with no one else. I do not remember consciously deciding that I would remain connected to Martha forever. Even to think of Martha was to be disloyal to my mother and all she was trying to accomplish, the normal life she was trying to give me. But my deepest, darkest secret—and also my most terrifying fear—was that it was now entirely up to me to keep Martha alive. For I had come to the terrible conclusion that my mother actually wanted Martha dead. Somehow it seemed that only I could sustain her existence by never forgetting her, by never severing our connection (Freeman, unpublished, pp. 57-59).

My sister lived at the Rideau Regional Centre for 13 years; we visited her there occasionally or she came home for short visits a few times a year. I am haunted by a second photo of her taken at the institution in 1970 when she was almost 12 (Figure 7). She stares defiantly into the camera; you can see her struggle to survive in that harsh environment, and her incredible strength, determination, and resistance. I don’t know what happened to her at Rideau, but in her file a social worker commented that she didn’t have the trust in adults that most children have.

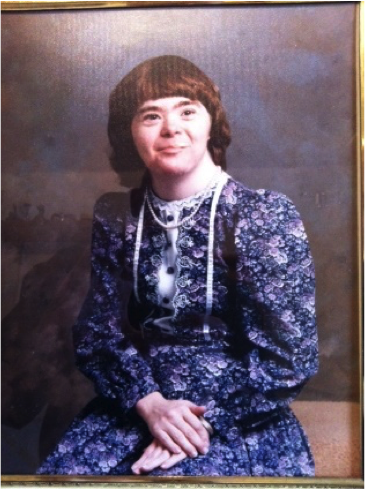

Martha was discharged to a boarding home in another city in 1973 when she was 15; she was informally adopted by the woman who ran it, living as a member of her family even after the boarding home closed. In fact, for 29 years, Eva Zaretsky (pseudonym), my sister’s saviour and protector, loved my sister as no one else ever had; miraculously, my sister found the love and acceptance she never received from her birth parents or the institution—or from me—and in many ways she flourished despite her very difficult early years. The transformation of my sister is evident in a photograph taken at this time (Figure 8). She looks confident, relaxed, and completely at ease with herself.

I on the other hand had a mental breakdown and dropped out of university when I was 20. I know I am lucky to be alive because I became delusional and dissociated and thought of killing myself every day for about six months. I was also followed around the streets of Toronto by strange men who sensed my vulnerability. My healing began only when I realized that as a four-year-old I had blamed myself for my sister being sent away—the source of my self-hate and psychic splitting. I had suffered the collateral damage of the decision to institutionalize my sister; a pervasive yet unacknowledged survivor’s guilt had left me vulnerable to an emotionally abusive boyfriend and a situation that almost destroyed me.

Eventually in 2012, ten years after my sister died, I had the opportunity to get involved with Sol Express, an all abilities Toronto performance group associated with L’Arche.

My excitement was quickly followed by mild anxiety about meeting the group, which soon deepened into fear and then a state of abject terror. I had never before voluntarily chosen to be with a group of people with Down syndrome; I had always avoided them or reacted with dread when I saw them, ever since visiting the hospital school as a young child. The Rideau Regional Centre had been a nightmarish and grotesque world where strange beings swarmed me and tried to touch me and grab me. I know now that this was because they were starved for love. It was supposedly an everyday place—a hospital, a school—but at its invisible heart was terror and horror and the indescribable pain of abandonment. In fact, it was a space of such extreme cognitive dissonance, causing such profound mental confusion in me, that it became the secret ‘crazy-making’ site and source of my own mental illness, papered over, hived off from the rest of my life until it could no longer be contained. ...It was an absolutely amazing, life-changing experience to meet the performers of Sol Express, and to dance and create theatre with them, especially because I had never believed my sister capable of creativity; that had been a marker of her perceived inferiority. As a lifelong dancer, it felt so special to now be able to dance and physically celebrate life and to create art with people like my sister, when so much of my relationship with her had been interrupted, deformed, or destroyed. Dancing with someone is fundamentally about relationship: there is dignity and respect when you meet at a creative level, when there is creative reciprocity. After the first wonderful day I spent with Sol Express I cried all the way home, and on and off for the next two days, I was so moved, so deeply affected, so grateful. I felt I had been touched at the very point where I had once been split in two, like a tree that had been riven right down the middle by lightning. I felt a welling up of love, and of my need to love. It was the love I was never allowed to feel before, a love I had been ashamed of, and which never had a chance to be. …The secret me that I had guarded for so long was suddenly larger, encompassed more people, had a life that was more than mourning, impossible pain, and impossible love. It opened out into joy and the end of my captivity; it was my own rebirth. At the same time I acknowledged a terrible truth: during her life I hadn’t even understood Martha as having feelings, as a soul needing to be loved. Forgive me, my sister, my dear sister. L’Arche and Sol Express have saved me; they have given me a place to put that love, a second chance (pp. 324-325, 332).

Conclusion

The narratives shared here give some indication of the pain experienced by people closest to those who were institutionalized. The decision to remove their brother or sister from the family home, or to not bring them home at all, was not theirs to make, and they suffered the repercussions and helplessness of their position acutely. Their descriptions of the life-long journey of coming to terms with their family story provide poignant indications of the extensive reach of institutionalization and the many thousands of lives it affected.

References

- Berton, P. (2013, September 20).Huronia: Pierre Berton warned us 50 years ago. The Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/news/insight/2013/09/20/huronia_pierre_berton_warned_us_50_years_ago.html.

- Dolmage, M. (2015, June 2). Missing Robert: Inspiration for Advocacy and Citizen Action. Presented at the Canadian Disability Studies Association 12th Annual Conference, Ottawa, ON.

- Freeman, V. Welcome: A Memoir. Book manuscript currently under review for publication.

- Freeman, V. (2015, June 2). Haunted: My Experience of My Sister’s Institutionalization. Presented at the Canadian Disability Studies Association 12th Annual Conference, Ottawa, ON.

- Malacrida, C. (2015). A Special Hell: Institutional Life in Alberta’s Eugenic Years. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- McLaren, A. (1990). Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada, 1885-1945. Toronto: McLelland & Stewart.

- Orrick, C. (2015, June 2). Valuing Gerry: Lessons from my Brother. Presented at the Canadian Disability Studies Association 12th Annual Conference, Ottawa, ON.

- Radford, J. (1991). Sterilization versus segregation: Control of the ‘feebleminded’, 1900-1938. Social Science in Medicine, 33(4), 449-458.

- Radford, J., & Park, D. (1993). “A convenient means of riddance”: Institutionalization of people diagnosed “mentally deficient” in Ontario, 1876-1934. Health and Canadian Society 1(2), 369-392.

- Simmons, H. (1982). From Asylum to Welfare. Downsview: National Institute on Mental Retardation.

- Williston, W. (1971). Present Arrangements for the Care and Supervision of Mentally Retarded Persons in Ontario. Toronto: The Queen’s Press.

-

At their peak in the 1960s, Ontario was home to three large “Schedule One” facilities and 13 smaller institutions that, while still funded by the provincial government, were run by local boards. It is interesting that the majority of these institutions, including the two additional large ones (Cedar Springs and Smiths Falls),were built between 1950 and 1970, at the same time that increasing awareness of the rights of people with disabilities began to have influence in policy decisions, and as the deinstitutionalization movement began to gain momentum. Despite these steps toward institutional closure, successive Progressive Conservative governments in Ontario, invested in keeping public opinion in their favour in the rural ridings in which these institutions were located, continued to expand Ontario’s institutional network. ↑

-

Detailed figures of the numbers of institutional residents are provided in Simmons (1982). ↑

-

In response to the revelations that hundreds of residents who died while living at the Huronia Regional Centre were buried nameless on the grounds of the institution, that stone markers used to mark the sites of graves had been moved and used for construction purposes, and that graves had been tampered with throughout the institution’s history, The Remember Every Name project has been undertaken by a group of survivors and friends whose goal is to identify and memorialize as many of the unidentified residents as possible, to call the Ontario government to account for the lack of respect afforded to residents’ burial sites, and to push the government to assume responsibility for the respectful upkeep of the Huronia cemetery. The Recounting Huronia project is an ongoing collaborative arts-based project involving Huronia survivors, artists, and faculty from a number of Ontario universities who are together “newly informing the public record” on Huronia through creative endeavours. The Surviving Huronia project was an art exhibit of survivors’ artistic work organized by Tangled Art + Disability in December 2014. ↑

-

In 2010, two survivors of the Huronia Regional Centre, Patricia Seth and Marie Slark, on behalf of former residents of HRC dating back to 1945, launched a class action lawsuit against the Ontario government for the mistreatment and abuse suffered by residents there. In December, 2013, the Ontario government offered an official apology to survivors of the Huronia Regional Centre and instituted a claims process whereby survivors could seek financial compensation for mistreatment and abuse. ↑