Shifting neurotypical prevalence in knowledge production about the mentally diverse:

A qualitative study exploring factors potentially influencing a greater presence of lived experience-led research

Damian Mellifont, Honorary Postdoctoral Fellow of the Centre for Disability

Research and Policy at The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

damian.mellifont@sydney.edu.au

Abstract: Research which is led by mentally diverse persons offers a variety of benefits. Crucially, this research holds potential to target wide-ranging social inclusion issues. Recognizing that these studies cannot lay claim to be commonplace, the aim of this investigation is to inform and improve policy supportive of lived experience-led studies by critically investigating evidence-based factors influencing a greater presence of this genuinely inclusive style of research. Following purposive sampling, thematic analysis was applied to twelve articles meeting with inclusion criteria and retrieved from Scopus, Medline, PsycINFO and ProQuest databases. This investigation reveals three key findings. First, this exploratory study identifies factors supporting and resisting lived experience-led research across micro, meso and macro levels. Second, investment in future research is needed to identify evidence-based measures with capacity to redress factors constraining opportunities for mentally diverse persons to develop research careers and to potentially lead the way in reforming mental health and other services. Finally, any assertions of neurodiverse researchers as necessarily being lacking in professional qualifications or reliant upon the assistance of neurotypical colleagues should be critically questioned.

Keywords:

- service user-led research

- consumer-led research

- emancipatory research

- neurodiversity

- Mad Studies

Declaration of interest: The author reports no funding support for this study and no conflict of interest.

Shifting neurotypical prevalence in knowledge production about the mentally diverse:

A qualitative study exploring factors potentially influencing a greater presence of lived experience-led research

Damian Mellifont, Honorary Postdoctoral Fellow of the Centre for Disability

Research and Policy at The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

damian.mellifont@sydney.edu.au

The goal of this exploratory study is to identify the factors with potential to impact upon the presence of genuinely inclusive studies whereby mentally diverse persons are responsible for leading research projects. These factors can play a notable role in either assisting or constraining the quantity of studies that are led by neurodiverse persons. Importantly, the reporting of these factors is to be evidence-based. That is to say, this investigative study will be informed by scholarly literature which covers the topic of lived experience-led research and more specifically delves into the ways in which the volume of these studies is potentially encouraged or discouraged. This critical investigation is of practical relevance as it will provide individuals who are interested in the social inclusion benefits that can be achieved through having more mentally diverse persons in lead research positions with insight into how this greater quantity might be advanced. This paper will begin by clarifying various terms used to describe research as led by persons who have lived experience with mental diversity (while recognising the complexities involved in attempts at making such clarifications), the benefits and current availability of these studies, along with the practical policy implications of this investigative study.

Research and mental diversity participation terminology

There exists a variety of terms within the literature which describe research being supported or led by mentally diverse persons. These terms encompass service-user led research (SULR), consumer-led research (CLR), survivor research, along with Mad Studies and neurodiversity scholarship. As will be elaborated upon, efforts to clarify these terms are complicated by their evolving, intersecting and at times conflicting meanings.

Service user, consumer and survivor-led research

In regards to the inclusion of service users in research that can potentially influence the quality of mental health and other services received (where such service support is needed and desired), involvement occurs at varying degrees. Service user participation can range from somewhat token roles through to service users participating in significant ways across all research phases (Simpson 2013, p.760 referencing Bowers et al. 2008). Taylor, Abbott, and Hardy (2012) explain that research over recent years have progressed an emancipatory style endeavouring to balance power relations among study participants and researchers. Nevertheless, ‘true’ emancipatory studies involve research being led by persons with lived experience (Smith-Merry, 2017, p.5 citing Boland et al. 2008). Possibilities therefore exist which allow a strengthening of service user participation beyond that of collaboration. Specifically, this is the level of SULR or CLR. SULR has been defined in terms of “‘research carried out by service users, with service users, for service users’” (Fothergill, Mitchell, Lipp, & Northway, 2013, p.747 citing Walsh & Boyle, 2009, p.31). The objective of SULR is to have the user voice positioned within the study agenda (Rose, 2015). Wykes (2003) also notes that the terms service user and consumer have been applied interchangeably. Indicating potential for a blurring of terminology, an overlap can thus be said to exist between SULR and CLR. Moreover, consumer activism which questions the efficacy of mental health services would inspire yet another brand of mental diversity-led research. To this end, survivor research would arise from the psychiatric consumer or mad movement as it tends to be described within Canada (Landry, 2017). As defined by Sweeney (2016, p.37), “survivor research can be considered the systematic investigation of issues of importance to survivors, from our perspectives and based on our experiences, leading to the generation of new, transferable, knowledges.” Jones (2017) recognizes that authority can be located within the deep pool of survivors’ understanding. Furthermore, Beresford (2000, p.169) notes how survivors of the psychiatric system can be exposed to discrimination. Exposure to discriminatory practices does not necessarily go unchallenged. Sweeney (2016) describes survivor research as being strongly connected within activism. Through the questioning of stigmatizing medical depictions of mental diversity, survivor research can be seen as having a political dimension.

Mad Studies

Mad Studies holds many similarities with survivor research. Aligning with survivor research, Mad Studies is also strongly connected with activism (Sweeney, 2016). Following Mad Studies recognition of psychiatric oppression, it remains unreceptive of mainstream services as delivered to the community (Cresswell & Spandler, 2016). Sweeney (2016) notes that Mad Studies offers an alternative to mainstream research which endeavours to simply obtain opinions regarding current services. Again, similar to survivor research, Mad Studies imparts hopefulness for the generation of radical new understandings as based upon the experiences of survivors (Sweeney, 2016). The power of Mad Studies comes from the enabling of strong partnerships beginning with survivors and survivor research (Beresford, 2016). However, not all agree that survivors should be at the epicentre of Mad Studies. While a Canadian construction of the term sees survivors as centrally positioned, understanding in the United Kingdom is constrained to “preserving space” for survivor researchers (Sweeney, 2016, p.43). Also reflecting its evolving nature, Beresford and Russo (2016) note that no exact or agreed upon definition involving Mad Studies is presently available. Nonetheless, Sweeney (2016, pp.37-38) citing LeFrancois, Menzies and Reaume (2013) attempts to define Mad Studies as, “an umbrella term that is used to embrace the body of knowledge that has emerged from psychiatric survivors, Mad-identified people, antipsychiatry, academics and activists, critical psychiatrists and radical therapists.” It should thus be acknowledged that this form of research has not developed in seclusion (Bereford & Russo, 2016). According to McWade, Milton, and Beresford (2015) and citing Costa (2014), Mad Studies and neurodiversity scholarship are emerging subjects of enquiry that endeavour to give an academic voice to persons who identify as Mad, survivors of psychiatric treatment, service users, consumers or neurodiverse (among others).

Elaborating on what it means to be neurodiverse, Marrero (2012, p.21) comments, “neurodiversity and neurodiverse are words that describe people who are diagnosed with disabilities that are rooted in neurological, cognitive, intellectual, developmental, or emotional differences such as autism, depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, learning disabilities, Down syndrome, or Williams Syndrome.” Offering an alternative to this medicalized definition of neurodiversity, O’Dell, Rosqvist, Ortega, Brownlow, and Orsini (2016) depict the concept in regards to its capacity to question mental normalcy and to promote positive constructions concerning mental diversity. More broadly, Baker (2011) recognises that the concept of neurodiversity is applied to capture all variances in the human mind that are not seen as typical. Indeed, an issue that is core to neurodiversity is that mental health conditions are indeed factual and neurological (Graby, 2015). However, psychiatric survivors tend to disapprove of medical views of their conditions and subsequently would not see themselves as psychologically compromised (McWade, Milton & Beresford, 2015). Nonetheless, while some survivor researchers might perceive their madness in a positive or neutral light, others may see it as problematic and necessitating support of a non-medical variety (Graby, 2015). Tensions might thus arise amid attempts to uniformly position those survivor or Mad researchers who see their mental diversity as something that is natural under a neurodiverse label which recognises mental health challenges and support needs. Moreover, Cresswell and Spandler (2016), while noting that Mad Studies see mental health treatment as a basis of oppression, proceed to question as to where does this leave people who do use psychiatric services and have positive experiences? Adding to this complexity, Graby (2015) notes that Mad Pride is something that many survivors refuse to identify with. Considering the Beresford and Russo (2016) recognition that Mad Studies holds prominent attachments to the widespread Mad Pride movement, another potential point of conflict arises among any possible attempt to uniformly label survivor researchers as Mad researchers.

Lived experience-led research

A term is available which seeks to address the possible tensions involved in grouping survivor and Mad researchers together under a Mad Studies label. This term is that of lived experience-led research (LELR). Byrne (2013) recognises that the discourse of lived experience is open to interpretation with no set definition currently available. Nevertheless, indicating potential for this term to be relevant to the field of mental health, Byrne, Happell and Reid-Searl (2015, p.935) state, “the term ‘lived experience’ refers to the unique perspective provided by people who have experienced significant mental health challenges, service use, and Recovery.” Banfield et al. (2018, p.2) also utilize the term ‘lived experience researchers’ to depict researchers who have mental health lived experiences and who make use of such experiences within their academic studies. Moreover, Voronka (2016) recognises the capacity of persons with lived experience in mental health issues to not only co-produce, but also to lead studies. As applied throughout the remainder of this paper and reflecting the scope of this exploratory study, the term LELR shall be taken as comprising research that is led by persons who may or may not identify as Mad, consumers of mental health services, survivors of psychiatric treatments, or neurodiverse. Aligning with this inclusive construction, LELR can thus be considered an overarching term which attempts to reflect individual lived experiences with mental diversity among persons who are leaders of research projects. Crucially, it is the factors which have potential to influence (both in positive and negative ways) a deep level of mentally diverse researcher involvement and control that is to be the focus of this investigative study.

LELR research benefits

LELR offers a variety of research benefits. Service users and survivors frequently discover research process and agenda possession to be empowering (Smith & Bailey, 2010 citing Mental Health Foundation, 2003). Within this perspective, Fothergill Mitchell, Lipp, and Northway (2013) suggest that user-led research endeavours to rectify power inequity. In relation to supporting research validity, the participation of individuals that utilize services is fundamental to constructing relevant research (Smith & Bailey, 2010 citing Entwistle et al. 1998). The literature also supports the value of SULR from a disability pride perspective. Williams and Lloyd (2014, p.207) citing Griffith et al. (2014) indicate that service user researchers can assist to de-stigmatize mental diversity. In contrast, Rose (2015) notes that conventional studies have held a medical focus with results tending to be appraised in regards to lowering symptoms. Mad and survivor-led research can instead lean towards more socially ambitious goals. Supporting this position, Sweeney (2016, p.40) states, “neither Mad Studies scholars nor survivor researchers are content to interrogate or generate knowledge for its own sake, but seek for their work to hold transformative and social justice goals.” Landry (2017) also advises that survivor research in Canada has targeted socially responsible topics including employment obstacles, safe houses, as well as the development of peer support. Survivor-led research thus has the capacity to target wide-ranging issues of social inclusion. Moreover, research which is designed, controlled and led by neurologically diverse individuals holds potential to challenge not only the research questions that are to receive scholarly attention, but also the ways in which these studies are to be undertaken. To this end, Voronka (2016) explains that by situating themselves and being situated as lived experience experts, individuals are called into managing and co-producing studies which provide opportunity to deeply unsettle prevailing approaches of conducting mental health studies.

Current representation of LELR

Debate exists around the extent to which mentally diverse persons are receiving opportunities to take on lead research roles. Beresford (2005) recognizes a record attention in the UK concerning research that is managed by service users. Simpson (2013) too notes a broad expectation of service user participation within research of a health or social support nature. Taylor, Abbott, and Hardy (2012) have also suggested that the views of service users are progressively being acknowledged as a significant factor in monitoring the achievement of a contemporary consumer-targeted health service. Despite these advancements, LELR research cannot lay claim to be commonplace. Landry (2017) cautions that so far, survivor research studies as carried out in the UK greatly outnumber those which are undertaken within Canada. Still, all is not going well for LELR presence across the UK. Rose (2015) has suggested of problems concerning the inclusion of service users within England’s mental health research. Further, while mental health policy has allowed service users to be actively partnering in Australian research over recent years, occasions where these persons hold a lead research position are comparatively uncommon (Williams & Lloyd, 2014). Simpson (2013) too recognizes the appearance of service user-led studies as being less typical. Nicki (2017) also reports that while Mad spaces are assisting the work of some survivor researchers, these environments are not immune from issues of hierarchy, exclusion and oppression. Nevertheless, positive signs do exist in support of a greater presence of LELR. A sense of optimism can be constructed in the Simpson (2013) suggestion that conceivable there will be additional publications commending fruitful SULR results in the coming years. Supporting this positive outlook, it should be realised that the mentally diverse researcher talent pool has potential to grow. In this regard, Faulkner (2017) makes the point that a greater number of service users as well as survivors are undertaking PhD level studies. Indeed, opportunities exist to construct fresh ways forward that are truly liberating for mental health service users (Stickley, 2006). By exploring ways in which research that is led by mentally diverse persons can be encouraged or hindered, this study holds practical policy implications. Specifically, within a dynamic environment of research benefits, opportunities and setbacks, this exploratory study aims to inform and improve policy support of LELR by critically investigating evidence-based factors influencing a greater presence of this genuinely inclusive style of research.

Methods

Data was collected by applying the following search criteria to Scopus, Medline, PsycINFO, and ProQuest databases: search term = “consumer led research” OR “service user led research” OR “lived experience led research”; document type = article; language = English; and publication date range = 2000 to 2017. These enquiry details were deemed suitable for producing a sample that was both contemporary and meaningful in content. Applying purposive sampling, texts were considered relevant where the accompanying inclusion criteria were met: article is accessible; article includes information about factors with potential to influence the quantity of lived experience with neurodiversity-led studies in positive and/or negative ways; and no duplicates. Articles meeting inclusion criteria were then assessed under guidance of the Braun and Clarke (2006) described approach to undertaking thematic analysis. This process involved: a) reading the texts and noting early thoughts; b) devising preliminary coding rules; c) identifying themes/sub-themes; d) constantly assessing themes/subthemes; e) refining themes/sub-themes and finalising names; and f) reporting upon analysis.

Results

A total of 23 possibly relevant articles were identified from the four databases after running the searches within each. These were comprised of: Scopus (nine possible articles); Medline (seven possible articles); PsycINFO (six possible articles) and ProQuest (one possible article). Of these possibly relevant texts, nine were removed as duplicates leaving 14 possible articles. A total of 12 of these articles met with the accompanying inclusion criteria and hence were identified as relevant. These consisted of: Scopus (six relevant articles); Medline (three relevant articles); PsycINFO (two relevant articles) and ProQuest (one relevant article). Results of thematic analysis as conducted within this exploratory study and including themes/sub-themes together with corresponding coding rules and exemplary quotes are provided in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 describes evidence-based factors with potential to increase the quantity of LELR research across: a) an individualized level, b) a group or organizational level, and c) a national or international level. Table 2 depicts factors constraining such research presence throughout these three levels. Within both tables, the coding rules and evidence (i.e. exemplary quotes from the literature supporting the existence of LELR enablers and resistance factors) have been openly availed so as to promote coding transparency and research rigor.

Table 1. LELR research support factors

| Theme: Enablers Coding rule: encompasses micro, meso and macro level factors supportive of a greater quantity of LELR research. |

| Sub-theme: Micro enablers (personal experience; personal empowerment) Coding rule: micro (i.e. personal/individualized) level factors encouraging a greater quantity of LELR research. Exemplary quotes: “Conventional research has focused on clinical issues and interventions such as pharmacological and psychological ones and outcomes measured largely in terms of symptom reduction with the occasional nod towards measures of quality of life. These concerns may not be those which matter most to service users and patients 1-3” (Rose, 2015, p.959). “Facilitation of focus groups by consumer researchers may act to reduce the power differentials between researcher and participants” (Marino, 2015, p.69 citing Rose, Evans, Sweeney, & Wykes, 2011). “Over the past two decades, user-led research has developed an ‘emancipatory’ approach aimed at equalizing a power-based relationship between the researchers and the participants” (Taylor, Abbott, & Hardy, 2012, p.449). “The service users and carers want academics/professional researchers to be their equal partners in this journey” (Wilson, Fothergill, & Rees, 2010, p. 37). “There are many levels of service user involvement in research, from service users being briefly consulted about particular aspects of a research project through to research that is led, carried out, and managed at all stages by service users in relation to mental health (Johnson et al., 2004)” (Taylor, Abbott, & Hardy, 2012, p.449). |

| Sub-theme: Meso enablers (LELR group attributes - research validity, practicality and sensitivity; organizational support for LELR) Coding rule: meso (i.e. group/organizational) level factors encouraging a greater quantity of LELR research. Exemplary quotes: “It presents an example of a service user empowerment and research training programme and outlines a potential model for a service user and carer-led research group” (Wilson, Fothergill, & Rees, 2010, p.32). “Over the last eight years I have had the privilege of being involved with several service user/survivor-led projects in mental health in the United Kingdom which have brought together a range of people’s experiences in relation to how they and we cope with distress” (Nicholls, 2007, p.90). “Once they had analyzed the results, consumers urged administrators to make enhancements to vocational services, based on the results” (McQuilken, 2003, p.64). “The INFORM researchers were also particularly mindful that some people might still be feeling distressed or “in crisis” even after several months had passed from their initial contact with the AT” (Taylor, Abbott, & Hardy, 2012, p.450). “There are university departments who employ service user researchers and even where service user researchers are in very senior positions, there are NGOs and there is a critical sector of independent researchers some of whom are veterans of 1996 – as I am myself” (Rose, 2015, p.960) |

| Sub-theme: Macro enablers (national LELR momentum; international LELR outcomes) Coding rule: macro (i.e. national) level factors encouraging a greater quantity of LELR research. Exemplary quotes: “For service user research in mental health we will not give up without trying to protect hard won gains” (Rose, 2015, p.960). “Employing their own research staff and commissioning work from others, they have brought a practical perspective to the working of regulation from the point of view of public protection and they have found it wanting” (Davies, 2004, p.S1:58). “The rate of loss reported was not related to whether the research had been led by those who had received ECT or by clinicians; however clinician led research tended to minimise the role of ECT on memory loss whilst service user led research tended to focus on the impact of the loss” (Fisher, 2012, p.594 citing Rose et al. 2003). “This juncture saw the completion of the closure of long-stay institutions in the UK” (Rose, 2015, p. 959). |

Table 2. LELR research constraint factors

| Theme: Resistance Coding rule: encompasses micro, meso and macro level factors constraining a greater quantity of LELR research. |

| Sub-theme: Micro resistance (individualized mental health challenges; personal power bases) Coding rule: micro (i.e. personal/individualized) level factors restricting a greater quantity of LELR research. Exemplary quotes: “individuals may be involved in other related activities or, at times, have to prioritise their own mental health needs” (Smith & Bailey, 2010, pp.42-43). “The first initiative failed because it is not easy even for conventional researchers who promote user involvement to work with those who take a strong view that research involving service users should be user controlled” (Rose, 2015, p.959). “professionals and service users researchers are likely to approach the research from a different perspective and value base.” (Smith & Bailey, 2010, p.43). “A further difference was that many user researchers were grounded in the service user movement which laid them open to dismissal as ‘political’ as if a preoccupation with violence was a neutral scientific issue” (Rose, 2015, p.959). |

| Sub-theme: Meso resistance (LELR group funding; LELR group exclusion) Coding rule: meso (i.e. group/organizational) level factors restricting a greater quantity of LELR research. Exemplary quotes: “The authors reflect on the challenges they faced in obtaining funding as an RDG, in developing and operating as a research group and in developing and submitting research funding applications” (Simpson, 2013, p.760). “Levels and types of involvement vary considerably from fairly tokenistic invitations to one service user representative to sit on a project steering group, through to genuinely collaborative efforts where services users are meaningfully involved in all stages of the research process and are employed as part of the research team (Bowers et al., 2008)” (Simpson, 2013, p.760). “healthcare professionals appear to be dominating consumer based research, with only a little over half of these projects actively involving the consumers or directly benefiting consumers” (Kirkpatrick, Roughead, Monteith, & Tett, 2005, p.75.6). |

| Sub-theme: Macro resistance (structural barriers; reporting of LELR support challenges; underreporting of LELR benefits) Coding rule: macro-level (i.e. national/universal) factors restricting a greater quantity of LELR research. Exemplary quotes: “More recently, Callard et al. (2011) have argued that ‘translational research’ that promises to fast-track biomedical advances in the service of patient benefit needs structural change to ensure that service users are also involved in all stages of these research programmes” (Simpson, 2013, p.761). “In conclusion, this study has reinforced findings from other service user-led research that it is time consuming and challenging to support service user-led research” (Smith & Bailey, 2010, p.43). “It is equally as important to identify and report the benefits, impacts and outcomes of user involvement in research – something that occurs too rarely still” (Simpson, 2013, p.761). |

Discussion

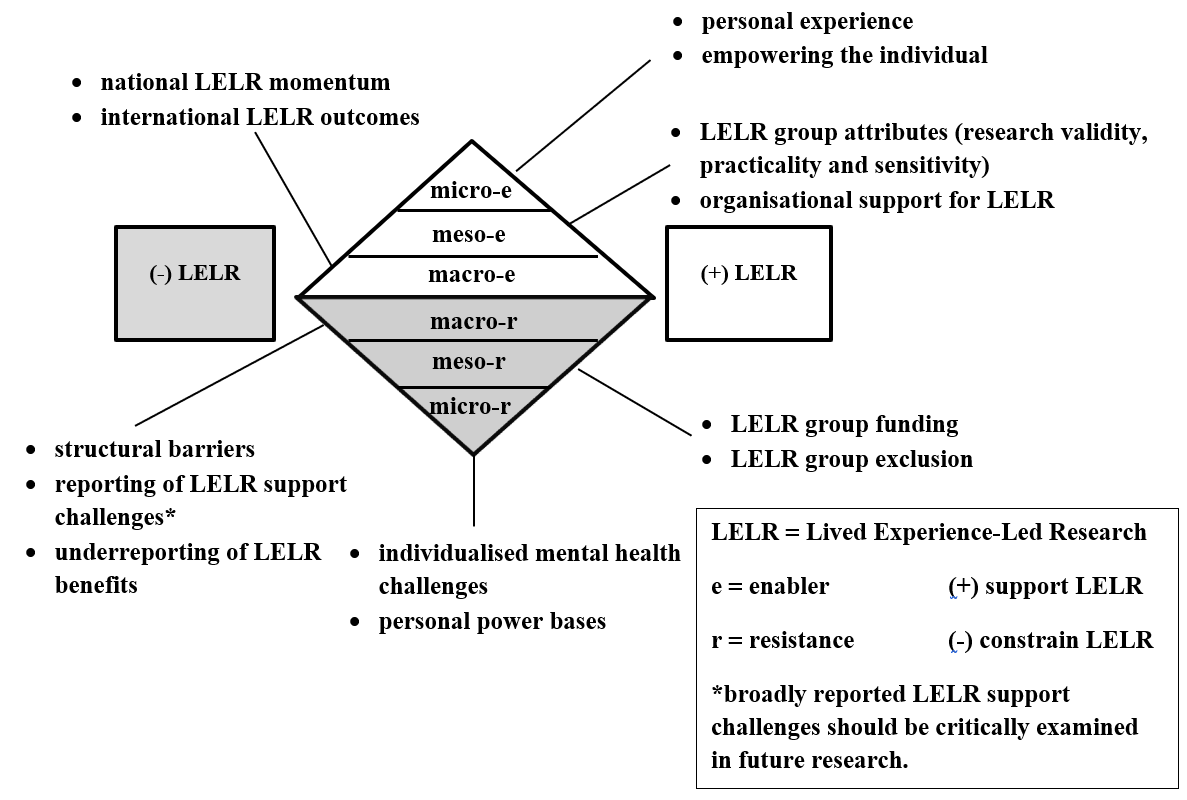

This section will critically discuss factors holding potential to promote or constrain the presence of LELR research as informed by the literature along with opportunities for future research. As illustrated in Figure 1, these factors will be covered across three levels of possible influence. Figure 1 shows these three levels of possible influence. These are shown in two triangles, one triangle showing how each level can be enabled, and one showing how each can be constrained. These levels encompass the micro or personal level, the meso group or organizational level and the macro national or international level. An overview of influences across these levels is provided as follows. At the micro level, personal experience and empowerment are described as LELR enablers while mental health challenges and personal power bases are identified as possible constraints. Moving onto the meso (i.e. group) level, LELR enabling factors of research validity, practicality and sensitivity together with organizational support are potentially limited by challenges in obtaining research funding along with an exclusion of neurodiversity from study teams. Lastly, at the macro level, enablers include capacity for LELR momentum to be demonstrated nationally along with the positive impacts of this style of research to be experienced internationally. Factors constraining large-scale LELR momentum include structural changes to established research networks, an overreporting of LELR support challenges (such reporting warrants critical investigation in future research) and an underreporting of LELR benefits.

Micro enablers of a greater quantity of LELR

Commencing at the micro level, the literature supports lived experience and empowerment of the individual as LELR enablers. Importantly, it is at this level where researchers who have lived experience with mental health services are potentially recognized and rewarded. Citing (Rose, 2003a), Waks et al. (2017) note that lived experience with mental ill health enables consumer researchers to raise distinctive study enquiries. Rose (2015) has also suggested that conventional studies have concentrated on clinical matters and that these issues might not be the ones that are of most importance to service users. Signifying medical model influences, traditional research may therefore inadvertently position mental diversity as a problem to be remedied. Conversely, grounding research in areas guided by personal experience may encourage progressive pathways to be explored which might otherwise be overlooked in studies which do not adequately value such knowledge. Furthermore, within a context of personal empowerment and control, Waks et al. (2017, p.2) comment:

Consumer-led research is distinct from other forms of consumer involvement in research in that consumer researchers hold ultimate decision making responsibility for all aspects of the research process including: designing the research question, developing the research method, data collection, analysis and report writing.

Empowerment of LELR thus needs to be genuine and pervasive throughout the research life cycle. The role of consumer researchers should in no way be constrained to the rubber stamping of ‘conventional’ research directives (i.e. directions that are set, controlled and monitored by neurotypical academics). Rather, it is appropriate that mentally diverse individuals are provided with career development pathways enabling them to demonstrate their research abilities and to be paid accordingly. To this end, these research opportunities and wages should be consistently availed at levels aligning with individual qualifications, skills and experience. Following on, it is feasible that by having more consumer researchers in positions where they have the power to set scholarly direction, we may also see additional studies moving beyond medically stigmatizing depictions of mental difference and towards ones which reveal socially responsible messages of inclusion and recognition of abilities. This possibility warrants future research enquiry.

Meso enablers of a greater quantity of LELR

Factors encouraging more mentally diverse researchers to embrace lead study roles exist at a group or organizational level. This is the level where the notable academic attributes that can accompany LELR may potentially assist in encouraging organizational approval and support. In this regard, scholarly evidence supports the ability of team members to draw on their lived experience as consumers of mental health services and survivors so as to progress studies which are valid, pragmatic and sensitive to the people who choose to participate in them. Reporting on a consumer-led investigation into the Australian Partners in Recovery service coordination initiative, Waks et al. (2017) comment about consumers leading research processes and how this leadership can support study relevance. Reinforcing the role of lived experience as an important factor contributing to research results that are both rigorous and practical, McQuilken et al. (2003) described a consumer-led study team who conducted a survey about employment motivations and perceived obstacles and involving 389 participants from an urban mental health facility. As this study was controlled by consumers, research validity was promoted through the questions that were asked as well as the data that was attained, which in turn assisted to generate notable vocational service revisions (McQuilken et al. 2003). These results indicate the capacity of researchers within a team setting to draw on their lived experiences as mental health service consumers and to deliver pragmatic research which is supportive of service reforms. The literature also acknowledges the attributes of survivor-led research. In particular, survivor researchers can support studies which are sensitive to the needs of study participants. This sensitivity is evident in the Taylor, Abbott, and Hardy (2012) paper which described the INFORM study group consisting of mental health survivors who investigated experiences of a crisis support and home treatment service. Reflecting lived experience researcher understanding of mental health challenges, Taylor et al. (2012, p.450) state:

A retrospective study was chosen because the INFORM group considered that it could be difficult for service users to take stock of their experience and to express their views in a survey, particularly while in a period of crisis or shortly afterward.

The above-mentioned example highlights the capacity of survivor researchers again operating in a team environment to be empathetic towards the mental wellbeing of study participants and to build this understanding into research designs. Recognizing LELR attributes of research validity, practicality and sensitivity to study participants, it should not be surprising to find instances of organizational support for such research. In this context, Rose (2015) recognizes that service users are being engaged as researchers in university and non-government organization environments. Future research is needed to examine the extent to which organizations are recognizing LELR benefits and are subsequently taking actions to recruit more mentally diverse researchers. Studies could also examine the degree to which these researchers once employed are empowered to set research agendas.

Macro enablers of a greater quantity of LELR

Literary evidence indicates that momentum supporting LELR presence can reach a national level with research outcomes holding international relevance. This means that the potential widespread impact of LELR should be acknowledged as a notable attribute of this genuinely inclusive style of study. Citing Faulkner and Layzell (2000) and Rose (2001), Rose (2015) describes two London based service user-led studies examining the experience of mental suffering which swiftly went national. Across England and before the year 2014, there were more than 800 persons self-identifying as mental health service users engaged with research (Rose, 2015 citing Patterson, Trite, & Weaver, 2014). An ongoing appetite for research that is led by service users and carried out at a national level should not be taken for granted. Rose (2015) notes that in the field of mental health service user research, people will not surrender without efforts to defend well fought wins . The prospect of attaining practical mental health outcomes on a wide scale is one conceivable driver of this defence. To this end, Simpson (2013, p.761) described LELR and its capacity to contribute to evidence-based policy as follows:

A good example is research undertaken by Diana Rose and her colleagues on electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) (Rose et al., 2003, 2005). Members of the research team had personal lived experience of ECT and the results of the study were published in two leading psychiatric journals and ultimately informed the NICE (2003) guidelines on ECT, and also had an impact on criteria for compulsory treatments for ECT under proposed new mental health legislation.

Raising potential for LELR to broadly influence how medical treatment options should be presented to mental health consumers, Fisher (2012) advises that psychologists need to safeguard that consent procedures are reflective of patient-led studies so that prospective patients have access to various viewpoints concerning ECT. In this way, LELR is both informative and empowering in that it holds capacity to widely avail information about the risks of particular treatments to prospective patients which might otherwise be overlooked or downplayed within medical model endorsed literature. Wilson, Fothergill, and Rees (2010) also recognize that service users want to play a role in broadly improving the mental health services received. Moreover, Rose (2015) described as no coincidence the closing of long-term stay institutions across the United Kingdom following SULR into the topic of mental suffering. Hence, SULR can be particularly powerful in the sense that it holds capacity to widely influence how mental health services are to be ethically and respectfully delivered internationally.

Micro resistance towards a greater quantity of LELR

Micro-level barriers to LELR raise the possibility of some mentally diverse researchers requiring individualized supports. Further, it is at this level where personal politics might play out with instances of neurotypical researchers anxiously protecting their established spaces within academia. Elaborating upon these possibilities, resistance to a greater level of LELR presence can be situated around individualized issues and include those of mental health challenges along with potential opposition from personal power bases. Aiming to investigate SULR obstacles as well as supports in a local National Health Service trust, Smith and Bailey (2010, pp.42-43) stated:

This study showed that there is a balance to be reached between involving people who use mental health services in designing and delivering research and recognising that these individuals may be involved in other related activities or, at times, have to prioritise their own mental health needs.

Remaining mindful of the above-stated findings, it is prudent to recognize that some researchers may experience challenges associated with their mental diversity. Aligning with the social model of disability, employers across public and private sectors should enthusiastically encourage these challenges wherever they might exist to be accommodated on an individualized basis. Despite opportunities and obligations to make adjustments in the workplace (where such accommodations are reasonable, required and requested), efforts to retain personal power bases may constrain a shift towards a greater level of mental diversity presence across research teams. Taylor, Abbott, and Hardy (2012) remark that user participation can be anxiety producing for all parties as it requires a shift in associations between professional researchers as well as service users. Nonetheless, it should be recognized that a proportion of mental health and other service users (along with mentally diverse persons who might have no need or desire to use these services) may hold professional research qualifications. Future investigation is thus needed to explore the possible extent to which neurotypical researchers might be anxious about the prospect of sharing more in the way of scholarly status and economic participation with post-doctoral researchers who are qualified not only academically, but also through their lived experience with mental diversity.

Meso resistance towards a greater quantity of LELR

Organizational (i.e. meso) level resistance to a greater presence of LELR encompass evidence-based factors of funding gaps and group exclusion. These meso-level factors are pertinent as they each contribute to the alienation of mentally diverse persons from participating in research projects. In terms of resourcing issues, Simpson (2013) describes as uncommon the instances of research where service users seek funding and subsequently design and perform the work. Given this underwhelming presence of research that is led by service users, further investigation is needed to identify the challenges that SULR teams might face throughout the various stages of funding application development and panel assessment. In particular, future research attention is required around potential complications following an automatic disclosure of disability in funding proposals. One particularly important area to explore is the possibility of mental illness stigma subconsciously influencing the decisions of some committees who are charged with assessing research proposals in a fair and objective manner. Potential for this particular form of discrimination to infiltrate and corrupt panel review processes should not be dismissed.

Consumers of mental health services may find themselves excluded from research opportunities. In an Australian study investigating how consumers have been collectively involved in Quality Use of Medicines projects, Kirkpatrick, Roughead, Monteith, and Tett (2005) remark that health professionals seem to be overshadowing consumer studies with just over half of the projects actively engaging with consumers. Decision makers should be called upon to illuminate why it is that consumers are being notably overlooked for these research projects. Exclusion of consumers of mental health services from research teams can have significant consequences in terms of the directions that studies ultimately take. To this end, Rose, (2015, p.959) citing Muijen, Marks, Connolly and Audini (1992) and Monahan et al. (2001) comments, “whereas conventional research both here and in North America was preoccupied with whether discharged patients posed a risk to the community, this was anathema to user-researchers some of whom knew first hand that the ‘community’ was far from welcoming”. It is therefore reasonable to suggest that researchers who have lived experience with mental health services tend to be well positioned to challenge instances of conventional research directions that potentially contribute to the stigmatization of mental diversity.

Macro resistance towards a greater quantity of LELR

The literature suggests that barriers to a greater presence of LELR occurring at a national or macro level reflect structural, support and reporting dimensions. Holding potential to influence the way in which mentally diverse researchers are widely perceived, it is at this level where the challenges of supporting SULR tend to be highlighted and the benefits understated. In addition, indicating a presence of structural barriers, Rose (2015, p. 960) remarks:

I intimated at the start that all is not well in the arena of service user involvement in health research and especially mental health research in England. The first reason for this is that the topic-specific networks, including the MHRN, have been dissolved into regional comprehensive networks with a diluted patient involvement element.

Care should thus be taken in network structural changes as these modifications have capacity to reduce the research participation of service users. Further, research as led by service users has been reported as being difficult to assist (Smith & Bailey, 2010). Remaining cognisant of such findings, investment is needed in studies to investigate potential cases of mentally diverse researchers who are working effectively either individually, as leaders or members of exclusive mentally diverse teams, or who are operating in other team compositions where their skills and abilities are such that they are not reliant upon the assistance of neurotypical colleagues. Crucially, it should not be assumed that researchers who identify with mental diversity cannot keep pace with their neurotypical colleagues. Indeed, where neurodiverse researchers are high-functioning, it is possible that the opposite might well be the case. Future studies are needed to examine this interesting prospect. And while there appears to be no shortage of reporting about support challenges involving SULR, Simpson (2013) highlighting the importance of reporting on the advantages and influences of user researcher participation, cautions of the infrequency of this coverage. Addressing this underreporting of LELR attributes at national and international levels may potentially have an influential part to play in advancing this genuinely emancipatory and socially responsible form of research.

Limitations

The author openly recognizes that this is an exploratory study which is limited to the targeted search term, databases and inclusion criteria applied. While the literary scope of this exploratory study is confined to the search term applied rather than any particular geographic location, the possibility that mentally diverse researcher-led studies might be conducted under different terms to those applied by this paper is acknowledged. The LELR support and resistance factors as revealed by this study may thus represent only a subset of those currently available from the literature. Being investigative, this study also raises several prospects to support a greater presence of this progressive style of research. Crucially, the capacity of each of these possibilities requires determination by future studies.

Conclusion

This exploratory study offers important messages for policymakers who are interested in advancing a greater presence of LELR along with goals of social and economic inclusion. First, this investigative research identifies factors supporting and resisting LELR across micro, meso and macro levels. Second, investment in future research is needed to identify evidence-based measures with capacity to redress factors constraining opportunities for mentally diverse persons to develop research careers and to potentially lead the way in reforming mental health and other services. Third, any assertions of mentally diverse researchers as necessarily being lacking in professional qualifications or reliant upon the assistance of neurotypical colleagues should be critically questioned. Finally, from a strategic standpoint, it is also important to recognize potential ideological implications following a shift in the status quo of neurotypical-dominated research. This includes possible movement away from medical model aligned research that tends to stigmatize mental difference and towards studies which endeavour to empower mentally diverse individuals both socially and economically. A healthy desire among policymakers and citizens alike in terms of wanting to see more LELR challenging negative depictions of mental diversity should be welcomed.

References

- Baker, D. L. (2011). The politics of neurodiversity: Why public policy matters. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Banfield, M., Randall, R., O’Brien, M., Hope, S., Gulliver, A., Forbes, O., Morse, A., & Griffiths, K. (2018). Lived experience researchers partnering with consumers and carers to improve mental health research: Reflections from an Australian initiative. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing.

- Beresford, P. (2000). What have madness and psychiatric system survivors got to do with disability and disability studies? Disability & Society, 15(1), 167-172.

- Beresford, P. (2005). Developing the theoretical basis for service user/survivor-led research and equal involvement in research. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 14(1), 4–9.

- Beresford, P. (2016). From psycho-politics to mad studies: Learning from the legacy of Peter Sedgwick. Critical and Radical Social Work, 4(3), 343-355.

- Beresford, P., & Russo, J. (2016). Supporting the sustainability of Mad Studies and preventing its co-option. Disability & Society, 31(2), 270-274.

- Boland, M., Daly, L., & Staines, A. (2008). Methodological issues in inclusive intellectual disability research: A health promotion needs assessment of people attending Irish disability services. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 21(3), 199–209.

- Bowers, L., Whittington, R., Nolan, P., Parkin, D., Curtis, S., Bhui, K., Hackney, D., Allan, T., & Simpson, A. (2008). Relationship between service ecology, special observation and self-harm during acute in-patient care: City-128 study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 193(5), 395–401.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Byrne, L. (2013). A grounded theory study of lived experience mental health practitioners within the wider workforce. Central Queensland University, Division of Higher Education.

- Byrne, L., Happell, B., & Reid-Searl, K. (2015). Recovery as a lived experience discipline: A grounded theory study. Issues in mental health nursing, 36(12), 935-943.

- Callard, F., Rose, D., & Wykes, T. (2011). Close to the bench as well as at the bedside: involving service users in all phases of translational research. Health Expectations, 15(4), 389–400.

- Costa, L. (2014). Mad Studies: What it is and why you should care. The Bulletin, 518, 4-5.

- Cresswell, M., & Spandler, H. (2016). Solidarities and tensions in mental health politics: Mad studies and psychopolitics. Critical and Radical Social Work, 4(3), 357-373.

- Davies, C. (2004). Regulating the health care workforce: Next steps for research. Journal of health services research & policy, 9(1_suppl), 55–61.

- Entwistle, V. A., Renfrew, M. J., Yearley, S., Forrester, J., & Lamont, T. (1998). Lay perspectives: Advantages for health research. British Medical Journal, 316(7129), 463.

- Faulkner, A. (2017). Survivor research and Mad Studies: The role and value of experiential knowledge in mental health research. Disability & Society, 32(4), 500–520.

- Faulkner, A., & Layzell, S. (2000). Strategies for living: A report of user-led research into people’s strategies for living with mental distress. London: Mental Health Foundation.

- Fisher, P. (2012). Psychological factors related to the experience of and reaction to electroconvulsive therapy. Journal of Mental Health, 21(6), 589–599.

- Fothergill, A., Mitchell, B., Lipp, A., & Northway, R. (2013). Setting up a mental health service user research group: A process paper. Journal of Research in Nursing, 18(8), 746–759.

- Graby, S. (2015). Neurodiversity: Bridging the gap between the disabled people’s movement and the mental health system survivors’ movement. Madness, distress and the politics of disablement, 231-244.

- Griffiths, K., Jorm, A., & Christensen, H. (2004). Academic consumer researchers: a bridge between consumers and researchers. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38(4), 191–196.

- Johnson, S., Bingham, C., Billings, J., Pilling, S., Morant, N., Bebbington, P., McNicholas, S., & Dalton, J. (2004). Women’s experiences of admission to a crisis house and to acute hospital wards: a qualitative study. Journal of Mental Health, 13(3), 247–262.

- Jones, C. (2017). Writing Institutionalization and Disability in the Canadian Culture Industry:(Re) producing (Absent) Story. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 6(3), 149–182.

- Kirkpatrick, C., Roughead, E., Monteith, G., & Tett, S. (2005). Consumer involvement in Quality Use of Medicines (QUM) projects–lessons from Australia. BMC health services research, 5(1), 75.1–75.7.

- Landry, D. (2017). Survivor research in Canada:‘Talking’recovery, resisting psychiatry, and reclaiming madness. Disability & Society, 1–21.

- LeFrançois, B. A., Menzies, R., & Reaume, G. (Eds.). (2013). Mad matters: A critical reader in Canadian mad studies. Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Marino, C. (2015). To belong, contribute, and hope: First stage development of a measure of social recovery. Journal of Mental Health, 24(2), 68–72.

- Marrero, E. (2012). Performing neurodiversity: musical accommodation by and for an adolescent with autism. The Florida State University.

- McQuilken, M., Zahniser, J., Novak, J., Starks, R., Olmos, A., & Bond, G. (2003). The work project survey: consumer perspectives on work. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 18(1), 5968.

- McWade, B., Milton, D., & Beresford, P. (2015). Mad studies and neurodiversity: A dialogue. Disability & Society, 30(2), 305-309.

- Mental Health Foundation (2003) Surviving user-led research. London: Mental Health Foundation.

- Monahan, J., Steadman, H., Silver, E., Appelbaum, P., Robbins, P., Mulvey, E., Roth, L., Grisso, T., & Banks, S. (2001). Rethinking risk assessment: the MacArthur study of mental disorder and violence. Oxford University Press.

- Morrigan, C. (2017). Failure to comply: madness and/as testimony. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 6(3), 60-91.

- Muijen, M., Marks, I. M., Connolly, J., & Audini, B. (1992). Home based care and standard hospital care for patients with severe mental illness: a randomised controlled trial. Bmj, 304(6829), 749–754.

- NICE (2003). Technology appraisal guidance 59: Guidance on the use of electroconvulsive therapy. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence.

- Nicholls, V. (2007). Loss and its truths: spirituality, loss, and mental health. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 15(2), 89-98.

- Nicki, A. (2017). Review of Russo, J. & Sweeney, A.(Eds.)(2016), “Searching for a rose garden: Challenging psychiatry, fostering mad studies”. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 6(4), 216-222.

- O’Dell, L., Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., Ortega, F., Brownlow, C., & Orsini, M. (2016). Critical autism studies: exploring epistemic dialogues and intersections, challenging dominant understandings of autism. Disability & Society, 31(2), 166-179.

- Patterson, S., Trite, J., & Weaver, T. (2014). Activity and views of service users involved in mental health research: UK survey. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 205(1), 68–75.

- Rose, D. (2001). Users’ voices: the perspectives of Mental Health Service users on community and hospital care. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

- Rose, D. (2003a). Collaborative research between users and professionals: peaks and pitfalls. The Psychiatrist, 27(11), 404–406.

- Rose, D. (2015). Reflections on the contemporary state of service user-led research. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(11), 959–960.

- Rose, D., Evans, J., Sweeney, A., & Wykes, T. (2011). A model for developing outcome measures from the perspectives of mental health service users. International Review of Psychiatry, 23(1), 41–46.

- Rose, D., Fleischmann, P., Wykes, T., Leese, M., & Bindman, J. (2003). Patients perspectives on electroconvulsive therapy: systematic review. Bmj, 326(7403), 1363.

- Rose, D., Wykes, T., Bindman, J., & Fleischmann, P. (2005). Information, consent and perceived coercion: patients’ perspectives on electroconvulsive therapy. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186(1), 54–59.

- Simpson, A. (2013). Setting up a mental health service user research group: A process paper. Journal of Research in Nursing, 18(8), 760–761.

- Smith, L., & Bailey, D. (2010). What are the barriers and support systems for service user-led research? Implications for practice. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 5(1), 35–44.

- Smith-Merry, J. (2017). Research to action guide on inclusive research. Centre for Applied Disability Research. Retrieved from www.cadr.org.au

- Stickley, T. (2006). Should service user involvement be consigned to history? A critical realist perspective. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 13(5), 570–577.

- Sweeney, A. (2016). Why mad studies needs survivor research and survivor research needs mad studies. Intersectionalities: A Global Journal of Social Work Analysis, Research, Polity, and Practice, 5(3), 36–61.

- Taylor, S., Abbott, S., & Hardy, S. (2012). The INFORM project: A service user-led research endeavor. Archives of psychiatric nursing, 26(6), 448–456.

- Voronka, J. (2016). The politics of ‘people with lived experience’ experiential authority and the risks of strategic essentialism. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 23(3), 189–201.

- Waks, S., Scanlan, J. N., Berry, B., Schweizer, R., Hancock, N., & Honey, A. (2017). Outcomes identified and prioritised by consumers of Partners in Recovery: A consumer-led study. BMC psychiatry, 17(1), 1–9.

- Walsh, J., & Boyle, J. (2009). Improving acute psychiatric hospital services according to inpatient experiences. A user-led piece of research as a means to empowerment. Issues in mental health nursing, 30(1), 31–38.

- Williams, P. L., & Lloyd, C. (2014). Service user-led research: should rehabilitation professionals be interested?. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 21(5), 207–207.

- Wilson, C., Fothergill, A., & Rees, H. (2010). A potential model for the first all Wales mental health service user and carer‐led research group. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing, 17(1), 31–38.

- Wykes, T. (2003). Blue skies in the Journal of Mental Health? Consumers in research. Journal of Mental Health, 12(1), 1–6.