Mapping Ableism: A Two-Dimensional Model of Explicit and Implicit Disability Attitudes

Carli Friedman, PhD, Director of Research, The Council on

Quality and Leadership

cfriedman [at] thecouncil [dot] org

Abstract: Nondisabled people often experience a combination of negative and positive feelings towards disabled people. There are often large discrepancies between what nondisabled and disabled people view as positive treatment towards disabled people, with disabled people often viewing nondisabled people’s actions as inappropriate, despite nondisabled people believing they had good intentions. Since disability attitudes are complex, both explicit (conscious) attitudes and implicit (unconscious) attitudes need to be measured. Different combinations of explicit and implicit bias can be organized into four different categories: symbolic prejudice, aversive prejudice, principled conservative, and truly low prejudiced. To explore this phenomenon, we analyzed secondary explicit and implicit disability prejudice data from approximately 350,000 nondisabled people and categorized people’s prejudice styles according to an adapted version of Son Hing et al.’s (2008) two-dimensional model of racial prejudice. Findings revealed most nondisabled people were prejudiced in the aversive ableism fashion, with low explicit prejudice and high implicit prejudice. These findings mirror past research that suggests nondisabled people may believe they feel positively towards disabled people but actually hold negative attitudes which they disassociate or rationalize. Mapping the different ways ableism operates is one of the first of many necessary steps to dismantle ableism.

Keywords:

- Modern prejudice

- ableism

- aversive ableism

- symbolic ableism

- social psychology

Mapping Ableism: A Two-Dimensional Model of Explicit and Implicit Disability Attitudes

Carli Friedman, PhD, Director of Research, The Council on

Quality and Leadership

cfriedman [at] thecouncil [dot] org

Disability is complex; as such, nondisabled people often experience a combination of negative and positive feelings towards disabled people (Czajka & DeNisi, 1988; Phillips, 1990). Disabled people are seen as less capable, less intelligent, more childlike, and more dependent than non-disabled people, they are also treated with pity and condescension (Fichten & Amsel, 1986; Ostrove & Crawford, 2006; Wolfensberger & Tullman, 1982). Disability beliefs, stereotypes, and tropes can conflict because they play different roles in different contexts (Barker & Wright, 1952; Wright, 1960). They tend to use disabled people as metaphors or plot devices where the disabled person serves to show the growth of another person (Heim, 1994; Longmore, 1987; Zola, 1985). For example, inspirational disability portrayals often serve to teach nondisabled people to appreciate their own lives and perpetuate the myth that the true disability is a bad attitude. These beliefs also often relate to nondisabled peoples’ projections of how they believe they would feel based on their limited understandings of and interactions with disability. Shakespeare (1996b) also cites the “critical role” prejudice and stereotypes play “in disabling social relations” (p. 192).

Conflicting Disability Narratives and Stereotypes

The succumbing framework (Wright, 1983) focuses on what disabled people cannot do and places in society in which they cannot participate (Adler, Wright, & Ulicny, 1991; Harris & Harris, 1977; Wright, 1960, 1967, 1978, 1980). Doing so ignores the richness of disabled peoples’ lives and exaggerates the negative of disability by focusing on pain, suffering, dependence, tragedy, and cure (Adler et al., 1991; Harris & Harris, 1977; Magasi, 2008, 2008b; Phillips, 1990; Wright, 1960, 1967, 1978, 1980). The succumbing framework in media and advertising is especially harmful because it helps define social roles and reinforce stereotypes (Dahl, 1993; Harris & Harris, 1977; Snyder & Mitchell, 2001).

Some disability narratives underestimate disabled people as they portray them as helpless, vulnerable, dependent, incompetent, helpless, and passive (Barker & Wright, 1952; Crawford & Ostrove, 2003; Davis, Watson, & Corker, 2002; Nario‐Redmond, 2010; Zola, 1985). These narratives are often associated with nondisabled people being paternalistic and infantilizing towards disabled people (Liesener & Mills, 1999).

Another prominent disability narrative portrays disabled people as less than and incomplete (Cahill & Eggleston, 1995; Longmore, 1987). Disabled people are often portrayed as maladjusted, self-pitying, and bitter as a result of their impairments (Hardin et al., 2001; Heim, 1994; Longmore, 1987; Schwartz et al., 2010).

One of the most prominent disability narrative is that of the inspiration. This disability narrative tends to manifest in two different directions, however both relate to “overcoming” disability. The first narrative is that disabled people are inspirational for their everyday activities. In the second inspirational narrative the disabled person achieves something extraordinary and triumphs against all odds over their impairment (Crawford & Ostrove, 2003; Dahl, 1993; Hardin et al., 2001; Kafer, 2013; Nario‐Redmond, 2010; Zola, 1985).

‘Positive’ Treatment

As a result of these narratives, disabled people are often objects of ambivalence that cause alternating favorable and unfavorable feelings in non-disabled people (Livneh, 1988). Although they may hold these problematic and negative views about disability, nondisabled people often ascribe positive socially desirable traits to people with disabilities. Positive feelings towards disabled people were noted even in early studies such as Strong Jr (1931) when disabled people held much lower social, economic, and political positions than they do now (Wright, 1960). Disabled people are often viewed as more affectionate, friendly, and warm than nondisabled people (Campbell, Gilmore, & Cuskelly, 2003; Harris & Fiske, 2007; Stern, Dumont, Mullennix, & Winters, 2007). Fichten and Amsel (1986) also found disabled people were commonly associated with the following traits: quiet, honest, gentile, non-egotistical, and undemanding. However, when disabled people deviate from these traits, they become associated with negative attitudes.

These beliefs (e.g., affectionate, friendly, warm) that associate disabled people with favorable feelings are problematic not only because they create unfair expectations but also because they tend to impact how nondisabled people interact with disabled people. For example, when Hastorf, Northcraft, and Picciotto (1979) had disabled and nondisabled confederates completed a task very poorly they found disabled people received inaccurate and less critical feedback compared to the nondisabled confederate. These so called ‘positive’ responses may be due to sympathy that marks disabled people as more deserving of help (Appelbaum, 2001; Czajka & DeNisi, 1988; Fichten & Amsel, 1986; Garthwaite, 2011; Imrie & Wells, 1993; Susman, 1994). People tend to be biased towards favoring disadvantaged people, even though disabled people’s disadvantages are often exaggerated (Rohmer & Louvet, 2018; Susman, 1994). For example, Murrell, Dietz-Uhler, Dovidio, Gaertner, and Drout (1994) found disabled people and the elderly were seen as more deserving of preferential treatment than Black people because their state was seen as outside of their control. Called a positive response bias or the sympathy effect by Susman (1994), nondisabled people will interact with and/or do small things for disabled people if they have no excuse to do otherwise. These positive responses result from overcorrection to avoid showing evidence of prejudice (Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986; Stern et al., 2007). For example, in another study by Czajka and DeNisi (1988) disabled workers were rated significantly higher than nondisabled workers except when there were performance standards. When norms were no longer ambiguous and their prejudice would have been more obvious they did not exaggerate disabled peoples’ performance. Well-meaning people may conform to social desirability pressures while still having implicit disability prejudice.

The theoretical underpinnings behind what constitutes a ‘positive’ disability attitude are still debated. For example, when Makas (1988) examined interactions between nondisabled and disabled people she found large discrepancies between what nondisabled and disabled people viewed as positive treatment towards disabled people. Disabled people often viewed nondisabled people’s actions as “‘inappropriate’” even though the nondisabled people believed they had the “‘best intentions’” (Makas, 1988, p. 50). For example, Makas (1988) found that while nondisabled people thought positive attitudes towards disability included being nice and helpful, disabled people thought positive attitudes towards disability included attitudes that defended their civil rights. This related to nondisabled people’s views that positive attitudes meant being nice and helpful to disabled people while disabled people thought they should be treated no different than a nondisabled person (Makas, 1988). Meanwhile, Yuker (1994) suggests contact is one factor that increases favorable attitudes of disabled people because comfort level with disabled people increases with exposure. He also suggests “for positive attitudes, the disabled person should be perceived as competent in the areas that are valued by the other [nondisabled] parties to the interaction” (Yuker, 1994, p. 7), suggesting that disabled people are rewarded with positive attitudes only when they uphold the ‘valuable’ yet artificial standards set for them by nondisabled people. Similarly, Söder (1990) cites others who believe positive disability attitudes are birthed by normalization such as mainstreaming. Söder (1990) also points out that those who critique labeling because it highlights difference are overly simplistic. These theories suggest that positive attitudes will happen automatically with the removal of difference.

Attitude Measurement

As “traditional methods leave little room for exploring this [disability] ambivalence” recently a number of studies have focused on implicit disability prejudice (Söder, 1990, p. 237). There are two level of attitude measurement: explicit (conscious) attitudes and implicit (unconscious) attitudes (Amodio & Mendoza, 2011; Antonak & Livneh, 2000). As people may feel pressured by social norms to conceal their biases, or may be unaware they hold biased attitudes, there are concerns that explicit measures do not capture a wide enough range of attitudes (Amodio & Mendoza, 2011; Antonak & Livneh, 2000). This may be especially true for topics where it is socially undesirable to have negative attitudes, such as against people with disabilities (Rohmer & Louvet, 2018). For this reason, much attitude research has shifted towards examining implicit attitudes. Implicit attitudes can relate to automatic processes triggered by external cues and reflect associations between attitudes and concepts; “‘implicit’ refers to [lack of] awareness of how a bias influences a response, rather than to the experience of bias or to the response itself” (Amodio & Mendoza, 2011, p. 359). Implicit attitudes have been studied extensively related to race, but less so for disability.

People’s explicit and implicit attitudes do not always align because explicit and implicit attitudes operate differently. Because they are measured differently and can be independent of one another, any individual’s combination of explicit and implicit bias can be organized into four different categories: symbolic, aversive, principled conservatives, and truly low prejudiced. Although less research has focused on implicit disability prejudice, disability’s designation as a social minority, analogous in some ways to race, allows for other theories about discrimination to be investigated for relevance to disability.

Symbolic racists are those who believe racial discrimination is no longer a serious problem, the special treatment of Black people is not justified, Black people are demanding too much too quickly and thus going beyond what is “fair,” and disadvantaged Black people are just unwilling to take responsibility for their lives (Henry & Sears, 2002; Sears & Henry, 2005). This form of prejudice is rooted in abstract beliefs about socialized values – internalization of social norms – which Black people supposedly violate, such as individualism (Henry & Sears, 2002, 2008; Sears, Henry, & Kosterman, 2000). Because it operates more subtly, symbolic racism is typically expressed through symbols (e.g., opposition to busing for integration). Symbolic racism is related to racial antipathy and conservative values.

Aversive racism refers to people who are progressive and well-meaning yet still participate in biased actions or thought (Dovidio, Pagotto, & Hebl, 2011; Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986). Egalitarian values are important to aversive racists’ self-image; they believe they are not prejudiced, yet they still feel discomfort around Black people and participate in biased action or thought in in ambiguous situations where it is harder to be “caught” being racist (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2008; Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986). When situations are not ambiguous and norms for behavior are well defined, people who score high on aversive racism will not participate in prejudiced acts but may actually go out of their way to appear non-prejudiced (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2008; Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986). Aversive racists have anxiety and discomfort around Black people, yet this prejudice is inconsistent with their self-concepts, and as a result, they rationalize or disassociate the products of these inconsistences by blaming them on factors other than racism.

Principled conservatives are those who truly value the abstract conservative ideas, which causes them to dislike policies that stray from societal tradition (Son Hing et al., 2008). Principled conservatives score high on explicit racial prejudice because they cherish traditional values and low on implicit racial prejudice because they discriminate against racial groups equally (Son Hing et al., 2008, p. 973). However, Son Hing et al. (2008) note “principled conservatism might not be a race-neutral ideology; rather racism and conservatism could be linked because both are used to legitimize hegemony” (pp. 972-973).

Finally, as the name suggests, truly low prejudiced people are those who exhibit low explicit and implicit prejudice (Son Hing et al., 2008).

Modern Disability Attitudes

Friedman’s (in press) study was one of the first to explore aversive ableism, including an exploration of the most prominent disability prejudice styles; however, as an exploratory study, Friedman’s (in press) study had a relatively small sample size of approximately 100 participants. Moreover, their participants were all undergraduate and graduate students. Thus, this study builds off Friedman’s (in press) study by exploring two-dimensional models of disability prejudice with a larger and wider sample.

This study’s hypothesis was that nondisabled are most often prejudiced in an aversive fashion rather than a symbolic one because of ‘positive’ treatment social norms, including those that imply people would look ‘bad’ overtly discriminating against disabled people. To explore this phenomenon, we analyzed secondary explicit and implicit disability prejudice data from approximately 350,000 nondisabled people and categorized people’s prejudice according to an adapted version of Son Hing et al.’s (2008) two-dimensional model of racial prejudice.

Methods

The Disability Attitudes Implicit Association Test (DA-IAT) is one of the most common methods to measure implicit disability prejudice. The DA-IAT presents participants with ‘disabled persons’ and ‘abled persons’ categories, and ‘good’ and ‘bad’ attitudes, and asks them to sort word and symbol stimuli accordingly. The DA-IAT examines people’s associations and attitudes by measuring reaction time when items are sorted in stereotype congruent and incongruent ways; the quicker the reaction time, the stronger the association between groups and traits (Karpinski & Hilton, 2001). Scores of .15 to .34 reveal a slight preference for nondisabled people, .35 to .64 a moderate preference, and .65 and greater a strong preference (Aaberg, 2012; Greenwald, Nosek, & Banaji, 2003). Negative values of the same values above reveal preferences for people with disabilities, and scores from -.14 to .14 reveal no prejudice (Aaberg, 2012; Greenwald et al., 2003).

Data about implicit disability prejudice were obtained from Project Implicit (Xu, Nosek, & Greenwald, 2014), a database where people can test their implicit prejudices, including against people with disabilities using the DA-IAT. A total of 344,760 nondisabled people took Project Implicit’s DA-IAT between 2006 and 2017. The majority of participants where White (77.31%) and women (70.76%) (see Table 1). Approximately half of participants (52.25%) had at least an undergraduate degree or higher. More than one-third of participants had a disabled family member (35.43%) or a disabled friend or close acquaintance (40.65%).

The explicit prejudice data were also from Project Implicit (Xu et al., 2014). The explicit prejudice measure was a single question that asked participants to rate their preference for disabled or nondisabled people on a 7-point Likert scale that ranged from strongly prefer disabled people to strongly prefer nondisabled people.

| Table 1 | ||

| Participant Demographics | ||

| Category | n | % |

| Sex (n = 268,582) | ||

| Female | 194,096 | 72.27% |

| Male | 74,486 | 27.73% |

| Race (n = 233,720) | ||

| White | 180,699 | 77.31% |

| Black or African American | 15,110 | 6.47% |

| East Asian | 7,681 | 3.29% |

| South Asian | 5,730 | 2.45% |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1,556 | 0.67% |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1,405 | 0.60% |

| Interracial | 11,888 | 5.09% |

| Other | 9,651 | 4.13% |

| Highest level of education (n = 306,164) | ||

| Some high school | 33,993 | 11.10% |

| High school graduate | 25,480 | 8.32% |

| Some college | 86,735 | 28.33% |

| Associate's degree | 22,272 | 7.27% |

| Bachelor's degree | 53,855 | 17.59% |

| Some graduate school | 32,112 | 10.49% |

| Graduate degree | 51,717 | 16.89% |

| Disabled family member (n = 256,051) | ||

| No | 165,342 | 64.57% |

| Yes | 90,709 | 35.43% |

| Disabled friend/close acquaintance (n = 255,135) | ||

| No | 151,435 | 59.35% |

| Yes | 103,700 | 40.65% |

In order to determine styles of prejudice, Son Hing et al.’s (2008) two-dimensional model of racial prejudice was used. In Son Hing et al.’s (2008) model, participants’ explicit and implicit scores are categorized as high and low and then grouped into four prejudice styles. People with high explicit and high implicit are symbolic prejudiced; high explicit and low implicit are principled conservatives; low explicit and high implicit are aversive prejudiced; and, low explicit and low implicit are truly low prejudiced. Once explicit and implicit scores were calculated we used this information to categories people as low and high and then group them into prejudice styles. Implicit scores were cut-off based on the moderate prejudice level (.35) according to IAT standards (e.g., Greenwald et al., 2003). The explicit score cut-off used was the moderate preference for nondisabled people (which was also the mean) on the Likert scale.

Results

Explicit Attitudes

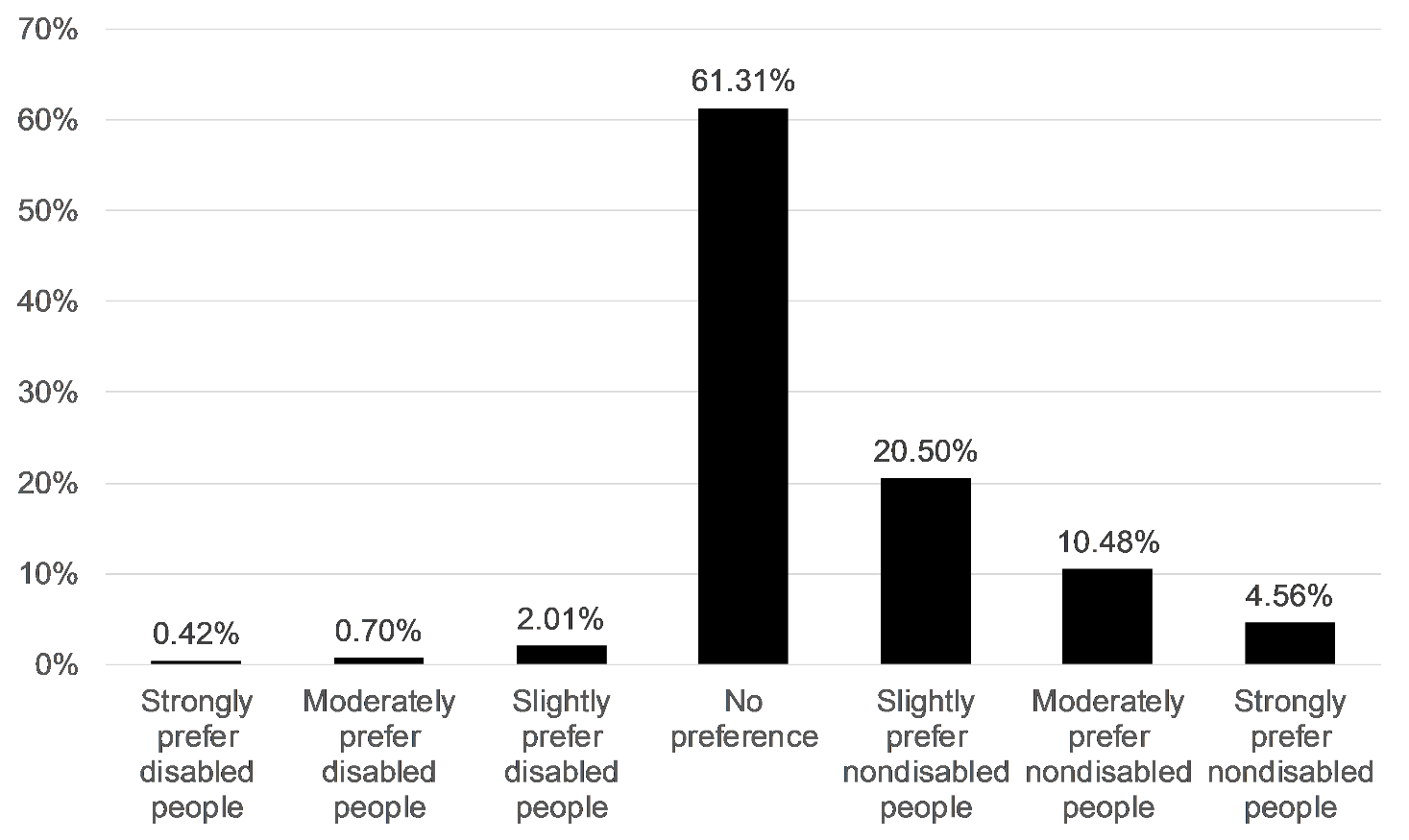

The explicit measures asked participants about their preference for disabled or nondisabled people on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly prefer disabled people” to “strongly prefer nondisabled people.” In this study, 3.14% (n = 10,830) reported preferring disabled people explicitly, 35.55% (n = 122,556) preferring nondisabled people, and 61.31% (n = 211,374) no preference. The majority of participants reported having no explicit preferences for nondisabled or disabled people; see figure 1 for the distribution of scores.

Implicit Attitudes

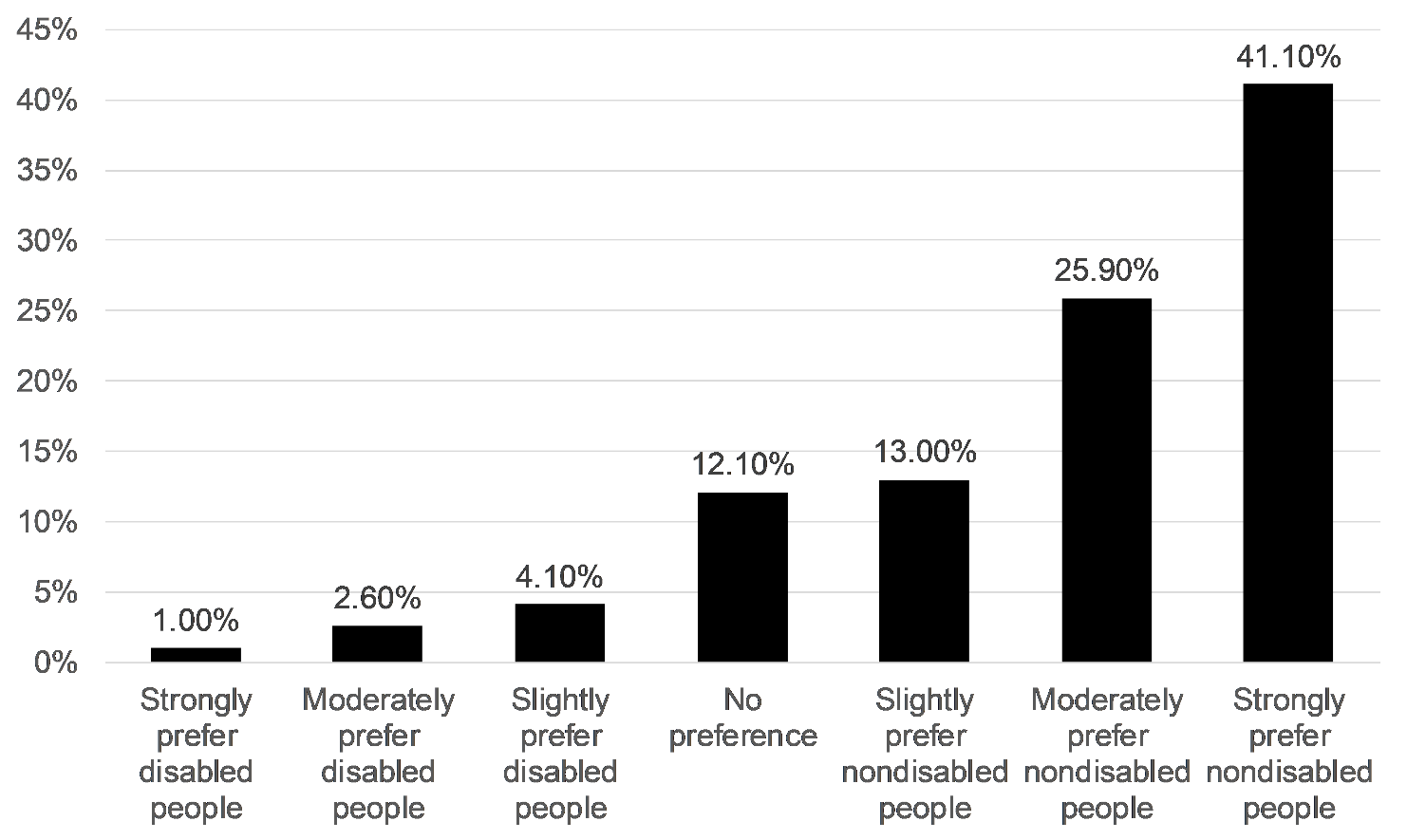

Implicit prejudice scores were calculated using Greenwald et al.’s (2003). Greenwald et al.’s (2003) updated IAT scoring protocol. Scores of 0 to .14 reveal no preference for nondisabled people, scores of .15 to .34 a slight preference, .35 to .64 a moderate preference, and .65 or greater a strong preference (Aaberg, 2012; Greenwald et al., 2003). Negative values of the

same ranges reveal preferences for disabled people, and -.14 to 0 scores reveal no prejudice (Aaberg, 2012; Greenwald et al., 2003). On the DA-IAT, the participants (n = 338,466) had a mean D score of .45 (SD = .44). This score was significantly different from zero according to a one-tailed t-test (t (338,465) = 669.16, p < .001), indicating an implicit preference for nondisabled people. In this study, 80.00% (n = 263,825) preferred nondisabled people implicitly, 7.70% (n = 25,642) preferred disabled people implicitly, and 12.10% (n = 39,733) had no preference. The majority of participants strongly preferred nondisabled people; see figure 2 for the distribution of scores.

Prejudice Styles

In order to determine types of prejudice present according to Son Hing et al.’s (2008) two-dimensional model of prejudice, participants’ explicit and implicit scores were categorized as high and low. Scores were then grouped into symbolic ableist (high explicit, high implicit), principled conservatives (high explicit, low implicit), aversive ableist (low explicit, high implicit), and truly low prejudiced (low explicit, low implicit). Once explicit and implicit scores were calculated we used this information to categories people as low and high and then group them into prejudice styles. Implicit scores were cut-off based on the moderate prejudice level (.35) according to IAT standards (e.g., Greenwald et al., 2003). The explicit score cut-off used was the moderate preference for nondisabled people (which was also the mean) on the Likert scale.

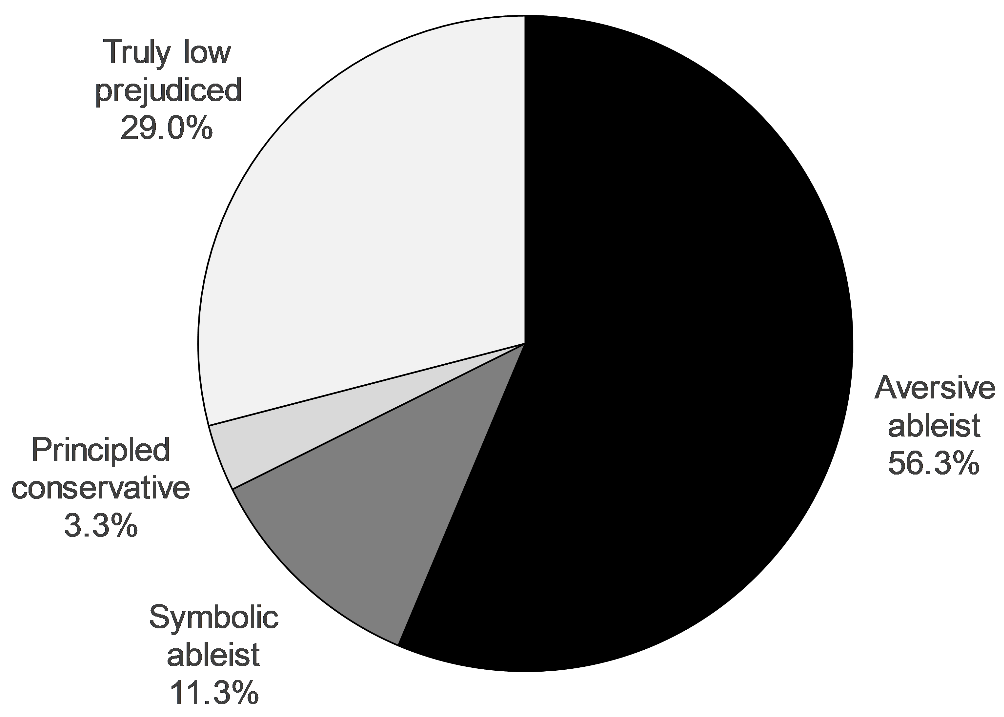

According to the findings, the majority of participants (n = 168,421) were aversive ableists, with fewer symbolic ableists (n = 33,808), principled conservatives (n = 9,872), and truly low prejudiced (n = 86,804); see figure 3.

Discussion

As disability attitudes are complex, nondisabled people often hold conflicting views towards disabled people. Social psychology research on prejudice suggests most people are prejudiced (Dovidio, 2001). Findings of this study from approximately 350,000 nondisabled people revealed most people were prejudiced in the aversive ableism fashion, with low explicit prejudice and high implicit prejudice. These findings mirror past research that suggests nondisabled people may believe they feel positively towards disabled people but actually hold negative attitudes.

Aversive ableism is the product of egalitarian values coupled with rationalized prejudice; the majority of those participants who said they felt positively towards disabled people strongly favored nondisabled people implicitly. According to aversive racism theory, aversive racists rationalize their prejudice because it is inconsistent with their self-concepts (Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986). Prejudicial treatment of disabled people is extremely justifiable because of the way negative associations with disability are individualized, naturalized (e.g., weakness, sickness, natural selection), and depoliticized (Kafer, 2013). Both implicit attitudes and aversive ableism are informed by internalization of societies’ (uninformed) disability attitudes (Amodio & Mendoza, 2011; Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986). The types of discrimination and prejudice that have been evidenced for so long in literature were still present among people who meant well –aversive ableists. As found in this study, aversive ableism appears to be much more prominent in the general population than symbolic ableism.

Indeed, only 11% of participants were symbolic ableists. Preliminary work on symbolic ableism has found four underlying themes: individualism; recognition of continuing discrimination; empathy for disabled people; and, excessive demands (Friedman & Awsumb, in press). Individualism is the idea that one can simply ‘pull oneself up by the bootstraps;’ individualism relies both on a Protestant work ethic narrative, wherein people have direct responsibility for their own outcomes, as well as a just-world ideology, wherein people are rewarded for their actions. Individualism and dislike for welfare systems may certainly interfere with their views of disabled people; however,

unlike the experience of many minorities, opposition to disability rights seldom has been marked by overt displays of bigotry or hostility; and politicians have often been included to provide sympathetic endorsements for the goals of disabled persons, even when they have shown strong resistance to the claims of other disadvantaged groups. (Hahn, 2005, p. 42)

As such, disabled people can violate individualism in two ways: based on stereotypes, they are seen as not working hard to get ahead and being a burden on the system as a result (i.e., individualism; excessive demands); and, they can work hard and still not get ahead (i.e., recognition of continuing discrimination, and empathy for disabled people) (Friedman & Awsumb, in press). However, even symbolic ableists’ empathy may be rooted in pity, paternalism, and ideas of ‘deservingness.’

Although it was a small proportion of participants (3%), over 10,000 nondisabled people were principled conservatives. In contemporary racism research principled conservatives are those who truly value abstract conservative ideas (Son Hing et al., 2008). For example, principled conservatives may be opposed to desegregation busing because they do not believe public money should be spent on busing. More research is needed to explore what principled conservatism related to disability might look like and what factors may relate to it. Principled conservatism may relate to fiscal/economic conservatism (Berdein, 2007), the implications of which are unknown for disability; this may be especially pertinent as disability and capitalism are often intimately intertwined. Perhaps an example of disability related principled conservatism might be someone who is against welfare systems because the person is truly fiscally conservative and are against these expenditures. However, the differentiation between this type of principled conservatism and someone who is prejudicially motivated requires in depth exploration, as there are many factors and narratives at play, including related to stereotypes regarding race, class, and disability. This also plays into the myth of the American Dream in which one can improve ones’ socioeconomic status with a good protestant work ethic, which ignores institutional prejudices. Berdein (2007) suggests a link between conservative principles such as work ethic and individualism and racial stereotypes. As there is a strong connection between disability and portrayals of uselessness (Cahill & Eggleston, 1995; Longmore, 1987), and disability is frequently individualized, principled conservatism related to disability needs to be further teased out. Moreover, as Berdein (2007) found, principles are not consistent across people, and some conservatives apply and abandon their principles differently depending on race, the differentiation between principled conservatism and symbolic ableism needs to be explored more in depth.

It was a bit surprising that 29% of the sample scored as truly low prejudiced given decades of research indicating ableism is extremely prominent (e.g., Abberley, 1987; Barnes, 1997; Baynton, 2001; Keller & Galgay, 2010; Linton, 1998; Shakespeare, 1996a; Young, 2014). We believe there may be a few possible reasons for this value. This higher than expected value may be related to the number of participants with disabled family members or close friends; members of both of these groups had lower levels of implicit prejudice and were therefore more likely to be truly low prejudiced. Moreover, the participants’ explicit attitudes were comprised of a single question about their preference for nondisabled or disabled people, rather than a full scale about this topic. Future studies should replicate this two-dimensional model of disability prejudice while using an explicit scale, such as the Symbolic Ableism Scale (Friedman & Awsumb, in press), instead. In addition, there are no standardized cut-offs for high and low for explicit and implicit prejudice levels; Son Hing et al. (2008) comment, “a potential problem with this approach [of classifying as explicit and implicit scores as high and low] is that cut-off scores are sample specific and malleable” (p. 983). This implication may be particularly true because the explicit score was based on participants’ answers to one question rather than a scale.

Future Directions

While this study was one of the first to explore two-dimensional ableism, including aversive ableism, especially on such a large scale, more research is needed to explore the similarities, differences, and interactions between aversive racism and aversive ableism. Aversive racists sympathize with those seen as victims of injustice. Clearly pity plays a large role with disabled people but how does sympathy impact the actions of aversive ableists? Aversive reactions are also likely to result from discomfort, disgust and fear, leading to avoidant behaviors. Discomfort and avoidance are commonly associated with disabled people; how might these associations drive the behaviors of aversive ableists?

Findings on aversive racism’s implications are also useful for the creation of the construct of aversive ableism. Aversive racism alters perception; even when a minority is well qualified the person may not be perceived as such (Dovidio, Mann, & Gaertner, 1989). How will aversive ableism interact with perception of disabled people, especially perception of ability? Moreover, Penner et al. (2010) found physicians’ perceptions of their own behavior was radically different from their patients’ perception as well as their own levels of implicit bias. How might disabled and nondisabled people have different perceptions of implicit bias?

Norms related to disability are more likely to be ambiguous. Norms related to disability are also often conflicting, which can contribute to ambiguousness. For example, it is not uncommon for disabled people to be portrayed as inspirational or pitiable in different contexts. In aversive racism, when the aversive racist does something wrong in ambiguous situations they disassociate the behavior from their self-image and avoid acting wrongly based on these feelings (Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986). When it comes to disability, ambivalent stereotypes may suggest behavior is ‘positive’ when some disabled people may not interpret it as such.

Aversive racists can also overreact and may actually respond more favorably to Black people when norms are clear (Aberson & Ettin, 2004). Even though they are favorable, these behaviors are still harmful in the long run. Aberson and Ettin (2004) point out

Whereas affirmative action increases opportunities, the tendency to exaggerate positive evaluations may ultimately deprive African Americans of opportunities. For example, in an educational setting, African Americans may receive excessive praise for good work. Though their performances were good, inflated evaluations of this sort may rob AAs [African Americans] of the criticism necessary to improve performance. (p. 43)

What would this mean for disabled people? What kind of ‘positive’ responses would result? Also because the behavior is deemed positive does not mean it is actually positive for disabled people. Or perhaps it is the aversive ableists’ overreaction that spurs pity and helping behavior in the first place?

In their study, Dovidio and Gaertner (1983) found high-ability partners were helped significantly more than low-ability partners and subordinates were helped more than supervisors. Meanwhile, Murrell et al. (1994) found disabled people and the elderly were seen as more deserving of preferential treatment than Black people because their status was outside of their control. According to Frey and Gaertner (1986), “more assistance is elicited by victims whose need, and thus dependency, is created by circumstances beyond their control than by victims more responsible for their dependency” (p. 1084). Helping behaviors have a unique history and interaction with disabled people because of their portrayal as subordinate, disadvantaged, and weak—needing help. If disabled people are always seen as low-ability and subordinate because of stereotypes does this account for why people are more compelled to help them? Participating in helping is also a function of attractiveness and cost (Dovidio & Gaertner, 1981, 1983). While stereotypes and misconceptions may negatively skew attractiveness, there is an extremely high cost for not helping disabled people. What are the implications of this when it comes to aversive ableism?

Finally, in addition to exploring these questions, another necessary next step to build upon this two-dimensional model of disability prejudice is to explore interactions with political orientation. Symbolic and aversive racism theories are linked with conservatives and liberals respectively. However, we theorize the differentiation between conservatives and liberals’ implicit disability prejudice may be less clear cut because of complex attitudes towards disabled people and social norms that portray disabled people as deserving of positive and favorable treatment. As a result, political orientation might not relate as neatly to prejudice styles related to disability as they do in aversive racism and symbolic racism research. Future research needs to explore this interaction further to better understand the ways different styles of prejudice operate.

Limitations

When interpreting these findings, it should be noted that people volunteered to participate and there is a chance of selection bias as a result. Moreover, the majority of participants were White and women, which is not a representative sample. Moreover, research suggests women may have more favorable attitudes towards people with disabilities than men (Hirschberger, Florian, & Mikulincer, 2005). It should also be noted that as this was a secondary data analysis we did not have the ability to add additional variables or ask participants additional questions.

Conclusion

Ableism is an extremely prominent problem that hinders the quality of life of disabled people. It manifests through structures and social systems, and also impacts daily interactions between people (Keller & Galgay, 2010; Linton, 1998). The disability prejudice style that was most prevalent in this study, aversive ableism, may be one of the most problematic to remove as aversive ableists rationalize and/or disassociate their prejudice – prejudice comes out in subtle and implicit ways perpetrators do not expect or are not aware of. Mapping the different ways disability prejudice operates is one of the first of many necessary steps to dismantle ableism.

References

- Aaberg, V. A. (2012). A path to greater inclusivity through understanding implicit attitudes toward disability. The Journal of nursing education, 51(9), 505-510. doi:10.3928/01484834-20120706-02

- Abberley, P. (1987). The concept of oppression and the development of a social theory of disability. Disability, Handicap & Society, 2(1), 5-19. doi:10.1080/02674648766780021

- Aberson, C. L., & Ettin, T. E. (2004). The aversive racism paradigm and responses favoring african americans: Meta-analytic evidence of two types of favoritism. Social Justice Research, 17(1), 25-46.

- Adler, A. B., Wright, B. A., & Ulicny, G. R. (1991). Fundraising portrayals of people with disabilities: Donations and attitudes. Rehabilitation Psychology, 36(4), 231-240. doi:10.1037/h0079085

- Amodio, D. M., & Mendoza, S. A. (2011). Implicit intergroup bias: cognitive, affective, and motivational underpinnings. In B. Gawronski & B. K. Payne (Eds.), Handbook of implicit social cognition: Measurement, theory, and applications (pp. 353-374). New York City: Guilford Press.

- Antonak, R., & Livneh, H. (2000). Measurement of attitudes towards persons with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 22(5), 211-224. doi:10.1080/096382800296782

- Appelbaum, L. D. (2001). The influence of perceived deservingness on policy decisions regarding aid to the poor. Political Psychology, 22(3), 419-442. doi:10.2307/3792421

- Barker, R. G., & Wright, B. A. (1952). The social psychology of adjustment to physical disability. Psychological aspects of physical disability, 18-32.

- Barnes, C. (1997). A legacy of oppression: A history of disability in Western culture. In L. Baron & M. Oliver (Eds.), Disability studies: Past, present and future (pp. 3-24). Leeds: The Disability Press.

- Baynton, D. C. (2001). Disability and the justification of inequality in American history. In P. Longmore & L. Umansky (Eds.), The new disability history: American perspectives (pp. 33-57). New York: University Press.

- Berdein, I. (2007). Principled conservatives or covert racists: Disentangling racism and ideology through implicit measures (Doctoral Dissertation). Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY.

- Cahill, S. E., & Eggleston, R. (1995). Reconsidering the stigma of physical disability. The Sociological Quarterly, 36(4), 681-698.

- Campbell, J., Gilmore, L., & Cuskelly, M. (2003). Changing student teachers’ attitudes towards disability and inclusion. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 28(4), 369-379.

- Crawford, D., & Ostrove, J. M. (2003). Representations of disability and the interpersonal relationships of women with disabilities. Women & Therapy, 26(3-4), 179-194. doi:10.1300/J015v26n03_01

- Czajka, J. M., & DeNisi, A. S. (1988). Effects of emotional disability and clear performace standards on performance. Academy of Management Journal, 31(2), 394-404. doi:10.2307/256555

- Dahl, M. (1993). The role of the media in promoting images of disability-disability as metaphor: The evil crip. Canadian Journal of Communication, 18(1).

- Davis, J., Watson, N., & Corker, M. (2002). Countering stereotypes of disability: Disabled children and resistance. Disability/postmodernity: Embodying disability theory, 159-174.

- Dovidio, J. F. (2001). On the nature of contemporary prejudice: The third wave. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 829-849. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00244

- Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (1981). The effects of race, status, and ability on helping behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 44(3), 192-203.

- Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (1983). The effects of sex, status, and ability on helping behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13(3), 191-205.

- Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2008). New directions in aversive racism research: Persistence and pervasiveness. In C. Willis-Esqueda (Ed.), Motivational aspects of prejudice and racism (pp. 43-67). New York: Springer.

- Dovidio, J. F., Mann, J., & Gaertner, S. L. (1989). Resistance to affirmative action: The implications of aversive racism. In F. Blanchard & F. J. Crosby (Eds.), Affirmative action in perspective. New York: Springer.

- Dovidio, J. F., Pagotto, L., & Hebl, M. R. (2011). Implicit attitudes and discrimination against people with physical disabilities. In R. L. Wiener & S. L. Willborn (Eds.), Disability and Aging Discrimination (pp. 157-183). New York: Springer.

- Fichten, C. S., & Amsel, R. (1986). Trait attributions about college students with a physical disability: Circumplex analyses and methodological issues. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 16(5), 410-427.

- Frey, D. L., & Gaertner, S. L. (1986). Helping and the avoidance of inappropriate interracial behavior: A strategy that perpetuates a nonprejudiced self-image. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(6), 1083-1090.

- Friedman, C. (in press). Aversive ableism: Modern prejudice towards disabled people. Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal.

- Friedman, C., & Awsumb, J. (in press). The Symbolic Ableism Scale. The Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal.

- Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (1986). The aversive form of racism. In S. L. Gaertner & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), Prejudice, discrimination, and racism: Theory and research (pp. 61-89). Orlando: Academic Press.

- Garthwaite, K. (2011). ‘The language of shirkers and scroungers?’ Talking about illness, disability and coalition welfare reform. Disability & Society, 26(3), 369-372. doi:10.1080/09687599.2011.560420

- Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. an improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(12), 197-216.

- Hahn, H. (2005). Antidiscrimination laws and social research on disability: the minority group perspective. In P. Blanck (Ed.), Disability Rights (pp. 343-361). Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Hardin, M. H., Lynn, S., Kristi Walsdorf, B., Hardin, M., Lynn, S., & Walsdorf, K. (2001). Missing in action? Images of disability in Sports Illustrated for Kids. Disability Studies Quarterly, 21(2).

- Harris, L. T., & Fiske, S. T. (2007). Social groups that elicit disgust are differentially processed in mPFC. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2(1), 45-51. doi:10.1093/scan/nsl037

- Harris, R. M., & Harris, A. C. (1977). Devaluation of the disabled in fund raising appeals. Rehabilitation Psychology, 24(2), 69-78. doi:10.1037/h0090915

- Hastorf, A. H., Northcraft, G. B., & Picciotto, S. R. (1979). Helping the handicapped: How realistic is the performance feedback received by the physically handicapped. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 5(3), 373-376. doi:10.1177/014616727900500321

- Heim, A. B. (1994). Beyond the Stereotypes: Characters with Mental Disabilities in Children's Books. School Library Journal, 40(9), 139-142.

- Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2002). The Symbolic Racism 2000 Scale. Political Psychology, 23(2), 253-283. doi:10.1111/0162-895x.00281

- Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2008). Symbolic and modern racism. In J. H. Moore (Ed.), Encyclopedia of race and racism (pp. 111-117). Farmington Hills, MI: Macmillan Reference.

- Hirschberger, G., Florian, V., & Mikulincer, M. (2005). Fear and compassion: A terror management analysis of emotional reactions to physical disability. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50(3), 246-257. doi:10.1037/0090-5550.50.3.246

- Imrie, R. F., & Wells, P. (1993). Disablism, planning, and the built environment. Environment and Planning C, 11, 213-213. doi:10.1068/c110213

- Kafer, A. (2013). Feminist, queer, crip. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Karpinski, A., & Hilton, J. L. (2001). Attitudes and the Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 774-788. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.774

- Keller, R. M., & Galgay, C. (2010). Microagressive experiences of people with disabilities. In D. W. Sue (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics and impact (pp. 241-267). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Liesener, J. J., & Mills, J. (1999). An Experimental Study of Disability Spread: Talking to an Adult in a Wheelchair Like a Child 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(10), 2083-2092.

- Linton, S. (1998). Claiming disability, knowledge and identity. New York: New York University Press.

- Livneh, H. (1988). A dimensional perspective on the origin of negative attitudes towards persons with disabilities. In H. E. Yuker (Ed.), Attitudes towards persons with disabilities (pp. 35-46). New York: Springer.

- Longmore, P. K. (1987). Screening stereotypes: Images of disabled people in television and motion pictures. Images of the disabled, disabling images, 65-78.

- Magasi, S. (2008). Disability studies in practice: A work in progress. Topics in stroke rehabilitation, 15(6), 611-617.

- Magasi, S. (2008b). Infusing disability studies into the rehabilitation sciences. Topics in stroke rehabilitation, 15(3), 283-287.

- Makas, E. (1988). Positive attitudes toward disabled people: Disabled and nondisabled persons' perspectives. Journal of Social Issues, 44(1), 49-61.

- Murrell, A. J., Dietz-Uhler, B. L., Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., & Drout, C. (1994). Aversive racism and resistance to affirmative action: Perception of justice are not necessarily color blind. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 15(1-2), 71-86. doi:10.1080/01973533.1994.9646073

- Nario‐Redmond, M. R. (2010). Cultural stereotypes of disabled and non‐disabled men and women: Consensus for global category representations and diagnostic domains. British Journal of Social Psychology, 49(3), 471-488.

- Ostrove, J. M., & Crawford, D. (2006). "One lady was so busy staring at me she walked into a wall": Interability relations from the perspective of women with disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly, 26(3). doi:10.18061/dsq.v26i3.717

- Penner, L. A., Dovidio, J. F., West, T. V., Gaertner, S. L., Albrecht, T. L., Dailey, R. K., & Markova, T. (2010). Aversive racism and medical interactions with black patients: A field study. J Exp Soc Psychol, 46(2), 436-440.

- Phillips, M. J. (1990). Damaged goods: Oral narratives of the experience of disability in American culture. Social Science & Medicine, 30(8), 849-857. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(90)90212-B

- Rohmer, O., & Louvet, E. (2018). Implicit stereotyping against people with disability. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(1), 127-140.

- Schwartz, D., Blue, E., McDonald, M., Giuliani, G., Weber, G., Seirup, H., . . . Perkins, A. (2010). Dispelling stereotypes: Promoting disability equality through film. Disability & Society, 25(7), 841-848.

- Sears, D. O., & Henry, P. J. (2005). Over thirty years later: A contemporary look at symbolic racism. In Advances in experimental social psychology, (Vol. 37, pp. 95-150): Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Sears, D. O., Henry, P. J., & Kosterman, R. (2000). Egalitarian values and the origins of contemporary American racism. In D. O. Sears, J. Sidanius, & L. Bobo (Eds.), Racialized politics: The debate about racism in America (pp. 75-117). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Shakespeare, T. (1996a). Disability, identity, difference. In C. Barnes & G. Mercer (Eds.), Exloring the divide: Illness and disability (pp. 11-16). Leeds: Disability Press.

- Shakespeare, T. (1996b). Power and prejudice: issues of gender, sexuality and disability. Disability and society: Emerging issues and insights, 191-214.

- Snyder, S. L., & Mitchell, D. T. (2001). Re-engaging the body: Disability studies and the resistance to embodiment. Public Culture, 13(3), 367-389.

- Söder, M. (1990). Prejudice or ambivalence? Attitudes toward persons with disabilities. Disability, Handicap & Society, 5(3), 227-241.

- Son Hing, L., Chung-Yan, G., Hamilton, L., & Zanna, M. (2008). A two-dimensional model that employs explicit and implicit attitudes to characterize prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(6), 971-987. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.971

- Stern, S. E., Dumont, M., Mullennix, J. W., & Winters, M. L. (2007). Positive prejudice toward disabled persons using synthesized speech does the effect persist across contexts? Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 26(4), 363-380.

- Strong Jr, E. K. (1931). Change of interests with age. Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press.

- Susman, J. (1994). Disability, stigma and deviance. Social Science & Medicine, 38(1), 15-22. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)90295-X

- Wolfensberger, W., & Tullman, S. (1982). A brief outline of the principle of normalization. Rehabilitation Psychology, 27(3), 131-145. doi:10.1037/h0090973

- Wright, B. A. (1960). Psychical disability—A psychological approach. In: Harper & Brothers, New York.

- Wright, B. A. (1967). Issues in overcoming emotional barriers to adjustment in the handicapped. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 11, 53-59.

- Wright, B. A. (1978). The coping framework and attitude change: A guide to constructive role-playing. Rehabilitation Psychology, 25(4), 177-183. doi:10.1037/h0090957

- Wright, B. A. (1980). Developing constructive views of life with a disability. Rehabilitation literature, 41(11-12), 274-279.

- Wright, B. A. (1983). Physical disability-a psychosocial approach: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Xu, K., Nosek, B., & Greenwald, A. (2014). Psychology data from the race implicit association test on the project implicit demo website. Journal of Open Psychology Data, 2(1), e1-e3. doi:doi.org/10.5334/jopd.ac

- Young, S. (2014). I'm not your inspiration, thank you very much. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/stella_young_i_m_not_your_inspiration_thank_you_very_much/

- Yuker, H. E. (1994). Variables that influence attitudes towards people with disabilities: Conclusions from the data. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 9(5), 3-22.

- Zola, I. K. (1985). Depictions of disability - metaphor, message, and medium in the media: A research and political agenda. Social Science Journal, 22(4), 5-17.