At Both Ends of the Leash: Preventing Service-Dog Oppression Through the Practice of Dyadic-Belonging

Devon MacPherson-Mayor, BA,MA

Critical Disability Studies, York University

devonmayor17 [at] gmail [dot] com

Cheryl van Daalen-Smith, RN, PhD

School of Nursing, York University

evandaal [at] yorku [dot] ca

Barkley the Poodle

Abstract

There is a growing interest in the “use” of service-dogs to enable people with disabilities to navigate the world more independently in North American culture. On the surface, while this may appear to be progress, the question remains, for whom? While there is evidence that the presence of a service-dog is beneficial for those living with a variety of disabilities, this trend is not devoid of embedded assumptions and a related need for caution. How disabled people are viewed and treated, matters. How nonhuman animals, in this case dogs, are viewed and treated equally matters. One set of needs stemming from structural oppression must not eclipse another’s set of needs. The use of one party in order to emancipate another, is therefore fraught with necessary cautions. There are shared oppressions and rights at both ends of the service dog leash.Keywords: Service-Dog, ableism, specieism, animal-rights, dyad

For Barkley, because you matter.

Introduction

There is a growing interest in the “use” of service-dogs to enable persons living with disability to navigate the world more independently in North American culture. While this may appear to be progress, the question remains, for whom? Although there is evidence that the presence of a service-dog is beneficial for persons living with a variety of disabilities, this trend is not devoid of embedded assumptions and a related need for caution. How persons living with disability and nonhuman animals, in this case dogs, are treated both matter equally. One set of needs stemming from structural oppression must not eclipse another’s set of needs. The “use” of one party in order to emancipate another, is therefore fraught with necessary cautions. There are shared oppressions and rights at both ends of the service dog leash.

Some argue that when a dog becomes a service-dog, they are enslaved to the human that they are paired with (Vegan Feminist Network, 2015). In fact, in a column entitled Assistance Dogs May Be Well Cared For, But Are They Happy? (2014), Arnold who founded Canine Assistants in 1995, stated, “I’ll just come out and say it-and expect to be attacked for saying it-but these dogs are slave labour. I don’t know how else to put it” (as cited in Dale, para.3). With service-dogs being requested to work beside people with disabilities, the concern is that these dyads will become unidirectional and based solely on the needs of the human. While in most cases, those provided with a service-dog do not purposefully disregard the dog’s needs, the risk is inadvertently succumbing to a speciesist mindset. But this one-sided, service-only relationship does not have to exist, if the rights of the service-dog are taken seriously with standards and policy.

With the demand for service-dogs exceeding the number of trained dogs available (Modlin, 2000), the necessity to ensure the rights of both parties is crucial. While arguments can be made that service-dogs can emancipate people with disabilities by enabling them to live more independently, there lacks sufficient attention regarding the impact on the dog nor an overt commitment to protect the dog’s welfare. As well, unless speciesist assumptions are addressed through language use, policy and oversight, there remains the risk that service-dogs may be exploited and valued only for what they can do for humans. Further, unless ableist assumptions are confronted within the service-dog provision, nothing of substance will really change concerning the rights and quality of life of persons living with disabilities. To that end, dyadic-belonging, a relationship grounded in reciprocity and shared rights, is proposed as a model for such pairings and fills a void in bringing forth both an animal and disability rights perspective to the discourse concerning service-dogs.

A term coined by the lead author whose partnership with her “service” dog Barkley meaningfully informs this analysis, dyadic-belonging as a model strives to inspire an ethos of non-hierarchical rights, steeped in bidirectional service that challenges problematic, speciesist assumptions relegating nonhuman animals to the service of humans. Dyadic-belonging acknowledges and lays bare, the question as to whether a service-dog provision can substantively change societal perceptions of disability in the absence of a social contract involving all of us.

This paper commences with a brief overview of the relevance of critical disability studies and critical animal studies in the prevention of service-dog oppression. A rationale for focusing on the rights of the service-dog will be provided, with an attention on the pervasive “use-value” narrative that reinforces speciesist beliefs. Dyadic-belonging will be presented as a principled antidote, tethered to a requisite social contract involving stakeholders, the service-dog dyad, the state, and all of us. Recommendations for national service-dog policy, training, and oversight grounded in animal welfare, together with a commitment to encompass the precautionary principle and embrace counter-hegemonic language, closes this commentary.

Critical Disability Studies and Critical Animal Studies

An analysis of the societal use of service-dogs must be situated in both critical disability studies (CDS) and critical animal studies (CAS). Despite what seems to be divergent concerns in each of these areas of critique, persons with disabilities and nonhuman animals share much. i.e. an outward focus on the rights, strengths and societal oppression experienced by disabled people or on the sentience, use-value or exploitative relationship of animals by humans. The assumptions regarding value, the denouncement of societal hierarchy and their work in challenging the power relationships that situate beings not perceived to be the societal “norm” in a place of structural and attitudinal oppression are just the beginning. Both demonstrate how binary notions of better than/less than have led to the mistreatment, exploitation, or marginalization of many groups, including nonhuman animals and people with disabilities (Nibert, 2008). At the vanguard of this link is disability activist and scholar Sunaura Taylor (2013) who argues that animal rights are instructively related to disability rights. The line, she argues, between human and animal is arbitrary, and that the same arguments about sentience, intelligence, and autonomy that are used to justify the inferiority (and therefore disposability) of animals to humans are used to deny many disabled people their rights and agency also.

CDS challenges ableist norms that perpetuate the belief that those living with disabilities are ill, flawed, and ‘something’ (not someone) that needs to be fixed (Reaume, 2014). Advocating for universal equality and accommodation (Reaume, 2014), CDS also confronts ableism which situates those with disabilities as “less than” their able-bodied counterparts (Grossman, 2014). Although past methods of looking at disability have focused on the medical model of disability, CDS is unique in that it acknowledges the sociopolitical tensions that occur outside of a medical diagnosis of disability (Meekosha & Shuttleworth, 2009). Despite contributing to many successes, one could argue that while striving to remove the binary between disabled and non-disabled people, CDS also makes it difficult for an individual or group to determine the specific areas where they are being marginalized. In this sense, “it is impossible to fight the oppression of a group of people that do not exist” (Vehmas & Watson, 2014, p.648). Many argue that while a trend towards pairing service-dogs with people with disabilities is progress, in that there is some degree of societal will to facilitate fuller integration of people with disabilities into society, a root question still remains: Does the support and provision of service-dogs fail to address underlying ableist beliefs concerning disability, or the labelling of so-called disabled bodies or minds?

CAS interrogates how the societal privileging of humans, more specifically non “disabled” humans, contributes to the domination and mistreatment of nonhuman animals (Nocella, Sorenson, Socha & Matsuoka, 2014). CAS’ ethos and core aim is the dismantlement of speciesism – a widely held belief which suggests nonhuman animals cannot feel, cannot think, are “ours” to use at will and grants, “humans moral standing, but unjustifiability accords animals of other species not, or only a lesser standing” (O’Neill, 1997, p.129). Unlike mainstream animal studies (AS), CAS is unique because of the activist and political stance it takes towards the liberation of all who are oppressed (Poiriern, 2016).

Society privileges some at the cost of others. In order to maintain systems of oppression, the process of marginalizing, denying rights, and the denouncing or rendering invisible articulations of lived experience that counter the status quo, is necessary. Hegemonic discourse maintains humans as more valuable than nonhumans and animate nature as more valuable than inanimate. Such thinking has led to the devaluation and exploitation of both nonhuman animals and nature, in the name of human interest. A complex field, within AS and CAS there exist various perspectives regarding how nonhuman animals can or should not interface with humans. Some argue for the complete emancipation of nonhuman animals, where they are not eaten, worked nor used in any manner for human gain. However, one could also argue that in seeking liberation for animals concerning labour, we deny them the opportunity to experience the benefits of being partnered with humans. In fact, it has been shown that dogs lead longer, safer and more comfortable lives with humans (Zamir, 2006) and furthermore, that rewarded labour suitable to dogs and their capacities provides much needed mental stimulation, wellbeing and happiness, not present in dogs who live idly or who lack a sense of purpose (Hens, 2009).

To be viewed as intrinsically less valuable and less capable, are two starting ways that people living with disabilities and nonhuman animals share the impact of social hierarchy. Withers (2012) cautions, “the consequences for falling outside of the norm can be devastating: institutionalization, abuse, poverty, loss of autonomy, dehumanization and eradication” (p.54). Furthermore, those in power “control the definition of what is normal, and, therefore, what is disabled, in order to maintain and expand influence and control their benefit” (p.108). Although speaking specifically about the construction of disability in society, this analysis can also be applied to power relations presiding over nonhuman animals, as those in control often redefine the meaning of animal in order to serve their capitalist interests. To be relegated to the margins of human society impacts the social and material lives of people with disabilities. But to never be considered a member of society, as in the case of nonhuman animals, is the ultimate marginalization. When left unchecked, speciesism maintains humans and therefore humanity as the pinnacle, with both animate and inanimate nature never considered as kin. According to Taylor (2017), just as ableism and its’ use of incapability arguments to substantiate the devaluation of persons deemed disabled, so too is ableism used to rationalize animal exploitation. Animals and people with disabilities share experiences of attitudinal devaluation where the same core goal fuels the marginalization: a toxic hierarchy which privileges the few at the cost of the many.

Engaging a dog in work as a “service”-dog, should not be taken lightly. It has implications for both the dog and the human partner. Facilitating the provision of service-dogs must not inadvertently reinforce ableist dependency myths about people with disabilities. And further, this arrangement must not recuse the state from its’ role in eliminating the barriers in the first place. In an effort to emancipate humans with disabilities from societally-induced barriers, we need to ensure that the dog’s wellbeing is also taken care of, not just because they are a “service-dog” or because they are deemed useful to humans, but because they deserve it in their own right. Because they have intrinsic value. Lived oppression can be found at both ends of the service-dog leash, but it is our contention that such a pairing can be mutually emancipatory. It starts with confronting hierarchy, embracing the necessity that there should be shared benefit to the partnership, that freeing one must not be at the cost of the other, that the rights of both parties matter equitably and that national policy, standards, and safeguards are a sustainable way to entrench such an approach.

For the purposes of this paper and grounded in the primary author’s own lived experience of sharing her life in complete partnership with a “service”-dog, it is argued that there is a way to prevent the enslavement of a canine while enhancing the quality of life for people with disabilities. A model of dyadic-belonging will now be proposed.

Dyadic-Belonging

Image 1.0

The lead author with her canine partner Barkley at graduation.

Dyadic-belonging is a reciprocal and non-hierarchical model buoyed by a reverence for the centrality of belonging. It is a rights-based approach which honours the deep love between a dog and his human companion, while politically confronting ableism and speciesism. Dyadic-belonging is associated with the following principles outlined in Table 1.0.

|

Table 1.0 The Principles of Dyadic-Belonging

Why a Dyad and Why Focus on Belonging?

According to Simmel (1950), the term dyad embodies the idea of reciprocal interaction and promotes egalitarian ways of being and thinking about the “other”. This is essential in the relationship between a service-dog and their human partner, as one does not have to look far to find examples of a unidirectional service-dog relationship. Even academia contributes to the normalization of this one-way relationship, with countless studies which focus on the benefits that service-dogs provide for humans, without any mention of the needs of the dog (Valentine et al., 1993; Yount et al., 2012; Eddy et al., 1988; Whitmarsh, 2005; Kwong & Bartholomew, 2011). With the current demand for service-dogs exceeding the number of trained dogs (Modlin, 2000), it is essential that we move past this mode of thinking to challenge problematic assumptions that nonhuman animals are here merely for the service of humans. The notion of a dyad is additionally relevant because of the potential for competing rights. Rather than what is often referred to as Oppression Olympics—which pits one group against another in arguments of greater oppressive conditions, a dyad invokes shared awareness and resistance, where both experiences of oppression matter equally (Dhamoon, 2009).

Belonging is associated with a “close or intimate relationship” (Merriam-Webster, 2019) and understood as acceptance as a valued and important member of a group (Hall, 2014). Rather than a service-focused arrangement, a partnership grounded in belonging is essential because dogs are by nature pack animals (Hens, 2009, p.12; Wenthold & Savage, 2007) and because a secure and loving bond between humans and dogs has mutual physiological and emotional benefits for both members of the dyad (Payne, Bennett and McGreevy, 2015). The relationship will evolve and emerge based on a synergy uniquely created in a reciprocal and non-hierarchical dyad buoyed in intentional partnership and belonging. Dyadic-belonging challenges ableism’s and speciesism’s flawed discourse . . . one dog and human companion at a time.

| Dyadic-belonging is a model that confronts ableist and speciesist hierarchy, embraces the necessity of reciprocity and mutuality within an egalitarian relationship between partners, ensures that the emancipation of one is not at the cost of the other, protects the rights of both parties equitably, and contends that national policy, standards, safeguards and societal participation are a sustainable way to entrench such an approach. |

An Unrelenting Focus on Use-Value

What Steeves is speaking to here, is a human tendency to regard nonhuman animals as mere machines or tools designed explicitly for human use. Along with service-dogs, there are many other examples of human-centeredness in society including horses pulling heavy carts, police dogs, cows providing milk for human consumption, rats subjected to damaging experiments, amongst others (Hribal, 2003; Swann, 2006; Coulter, 2016). The positioning of nonhuman animals as machine or tools for human use has persisted for hundreds of years by highly recognized scholars and thinkers. Aristotle famously stated, “other animals exist for the sake of man, the tame for use and good, the wild, if not all, at least the greater part of them, for food, and for the provision of clothing and various instruments” (as cited in Regan, 2001, p.6). To Descartes, nonhuman animals were understood as mechanistic in nature stating, “doubtless when the swallows come in spring, they operate like clocks” (cited in Taylor, 2013, p.25). When a nonhuman animal’s essence is compared to that of tools or machines, they become an object, leading to unjust and unethical treatment. This objectification denies the fact that nonhuman animals are sentient beings with intrinsic value, focusing solely on their usefulness or “use-value”.

Marx’s critique of capitalism gave rise to the term “use-value” which by definition is “the qualitative aspect of value, i.e., the concrete way in which a thing meets human needs” (Blunden, 2008, para.1). Service-dogs are conceptualized where they are required:

to be specifically trained to perform certain tasks. They must do something. They must perform a service such as guiding, picking up dropped keys, counterbalancing dizziness, or turning on the lights. The calming or therapeutic effect of their company is not enough. (Oliver, 2016, p.270)

Another illustration of the unrelenting focus on use-value, is the equally un-relenting necessity that people with disabilities must articulate exactly what they “need” a dog for. Service-dogs are then grouped alongside equipment like assistive aids and wheelchairs within government reports and laws (Oliver, 2016), further reinforcing a myopic use-value narrative. For example, in the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (2005), section 2a states that disability is:

any degree of physical disability, infirmity, malformation or disfigurement that is caused by bodily injury, birth defect or illness and, without limiting the generality of the foregoing, includes diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, a brain injury, any degree of paralysis, amputation, lack of physical co-ordination, blindness or visual impediment, deafness or hearing impediment, muteness or speech impediment, or physical reliance on a guide dog or other animal or on a wheelchair or other remedial appliance or device. (Government of Ontario, 2015, p.2)

Here, as Oliver (2016) points out, service-dogs are presented as a device alongside other remedial equipment such as wheelchairs. Similar wording is also present in the Saskatchewan Human Rights Act (2011) and the Prince Edward Island Human Rights Act (1988). Such illustrations of a use-value narrative, devoid of any mention of a dog’s intrinsic value, demonstrate how service-dogs’ relegated inferiority and subordination are maintained (Oliver, 2016). With this sentiment so pervasive, it is no wonder that the speciesist hierarchy continues leads to the troubling belief that as soon as nonhuman animals no longer provide a “use-value” for humans; they cease to be relevant or worthy.

The Rise of the Fake Service-Dog

According to Hopper (2018), there is a North American epidemic of “fake” service-dogs causing unnecessary confusion impacting both members of authentic service-dog dyads. The importance of creating a nationwide policy and standardization process is exacerbated because of this. At present, falsified service-dogs often come from two sources. The first is from people equipping their “pet” canine with a service-dog vest, tag and/or registration papers purchased from an online marketplace, without any training, assessment, or authentication. The second is by organizations who claim to be service-dog trainers, taking people’s money and then providing the individual with a dog that lacks the necessary training. Although people committing these guises often think their actions are harmless, such deception and the corollary delegitimization of actual service-dog dyads are anything but. As a result of this rising dishonesty, is the creation of social distrust which has devastating effects on people with disabilities who are subsequently forced to humiliatingly explain (over and over and over) their “impairment” or “problem” simply in order to gain entry somewhere. This is a gross injustice, rights breach, and further marginalizes a population already prone to social isolation.

Work and Value

CDS provides important critique of ascribing value concomitant to ones’ capacity to work. Taylor (2004) introduced the “right to not work”, as a way to challenge dominant ideologies that view those with disabilities as unproductive citizens. This deeply entrenched way of viewing disabled people as ineffectual can also provide context to the way that society views service-dogs, especially when they are no longer able to help their human companion. In many cases, when a service-dog retires, they are separated from their human partners creating undue stress and demonstrating a dismissal of the impact of separation on canines (Kwong & Bartholomew, 2011). Furthermore, since service-dogs often retire for reasons of illness or old age, the suggestion that this somehow makes them less valuable is rooted in their identity being solely defined by their service to a human. Service-dogs are more than just their job. First and foremost, they are sentient beings who have feelings and desires that should be respected and honoured regardless if they are working or not. Dyadic-belonging contends that either policy or legislation is warranted in order to protect the service-dog’s emotional needs while the dog is working and after their role is complete.

A Social Contract - Society's Obligation

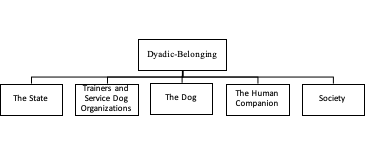

Donovan’s assertion illustrates that good intentions are not enough. There are many moving parts in this trend, including the dogs themselves, various agencies advocating for people with disabilities, store and restaurant owners questioning the validity of this movement, trainers and service-dog organizations and society as a whole including those who would falsely “certify” dogs or sell fake patches through online platforms. A social contract is understood as “an actual or hypothetical agreement among the members of an organized society that defines and limits the rights and duties of each” (Merriam Webster Online Dictionary, 2019). A social contract, depicted in Figure 1.0, is proposed as a means to ensure the enactment of dyadic-belonging where all parties enter into a covenant that explicitly seeks beneficence for all while putting safeguards in place in order to prevent unintentional maleficence.

Figure 1.0 - Rights-Based Service-Dog Social Contract

The State's Role

Current federal and provincial legislation in Canada ensures the entry of service animals to public spaces including university classrooms, airplanes, shops, etc. With the growing trend towards fake service-dogs and rising costs associated with training service-dogs, the state’s role has room for growth. Access to a properly trained service-dog remains cost prohibitive, especially if human companions are not able to obtain a dog from a non-profit organization (Wirth & Rein, 2008). In so being, this creates further inequity for human partners, which can also have a trickle-down impact on the ability to provide healthy food or veterinary care for the dog. While critiques are valid for viewing service-dogs as assistive “devices”, this remains one way in which some provinces provide for partial funding.

If the state appreciates the work provided by service-dogs, not only must it attend to the rights and well-being of the dog while he is in service, but this care must extend into the dog’s retirement. There needs to be programs in place in order to avoid the distress and uncertainty associated when their human partner passes away. As well, policies protecting dogs no longer “needed” or wanted by their human companion must be proactive, with requisite involvement of service-dog organizations. To that end, the implementation of a state-sponsored pension plan for service-dogs after retirement, similar to the one in the UK for police dogs (Pleasance, 2013), can ensure at a minimum that medical bills and associated costs will be covered, thereby potentially preventing the neglect or discarding of service-dogs no longer deemed “necessary”. The recent Medical Expense Tax Credit implemented by the Canadian Government is a step in the right direction, providing tax relief towards the cost of training and care of service-dogs (Government of Canada, 2018).

The Human Companion's Role

Suggesting that in this proposed social contract, there is a specification for the human half of the service-dog dyad may be startling to some, wondering if the rights and quality of life of people with disabilities in a culture of ableism, are still imperative. They are. They must be. The focus on the rights and oppressions faced by nonhuman animals is our shared imperative, as the oppression of one is tied up in the oppression of others. In a 1979 speech during the LGBTQ march in Washington, Audre Lorde famously proclaimed, “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own” (Cited in Lorde, 2007). Her point is that until we are all free, no one is free. Dyadic-belonging promotes a both/and approach, mutually appreciative of shared rights and thereby augmenting wider emancipation efforts. Kim (2015) similarly argues when oppressed groups are left to argue their own case, they often do so through a single optic lens, elevating their needs as more important than other marginalized groups. This, she laments, leads to mutual disavowal (Kim, 2015). Applicable to the service-dog dyad, she invites oppressed groups to embrace mutual avowal which, “plays on the productive possibilities of boundary crossing, and shakes up group identities by emphasizing the intimate connections among domination’s multiple forms” (p.198-199) and provides, “an open acknowledgement of connection with other struggles” (Kim, 2015, p.20). When the human partner seeks to prevent the oppression of their canine partner, they are not usurping their own rights. They are joining together mutually to confront hierarchy as a whole.

The Need for a National Training Standardization (Grounded in CDS and CAS)

In Canada, standardized training for agencies or individuals pairing dogs with humans does not exist. The same holds true for the training of would-be human partners. Before any organization or individual can send a dog for testing, we propose that they have successfully completed nationally accredited training with a focus on animal welfare, disability rights, service-dog and human matching techniques, as well as dog training principles grounded in animal rights and welfare. Furthermore, those who are being partnered with a service-dog where possible, should successfully complete accredited training from a governmental organization which also focuses on service-dog rights and welfare. Unquestionably, formal oversight to ensure that people are following these standards will ensure that the needs of the service-dog remain central over the course of their partnership and afterwards. To that end, we propose a single federal service-dog organization.

The NEed for National Service Dog Policy and Post Placement Oversight

Although British Columbia introduced provincial-wide legislation (Province of British Columbia, 2015), there remains a need for nation-wide service-dog policy. Over the past few years, there have been moderate efforts to create a national service-dog policy, through a partnership between the Canadian General Standards Board (CGSB) and Veterans Affairs. Unfortunately, despite the lead author’s involvement in this policy work and her provision of various recommendations based on her lived experiences, this work was suspended in April 2018 (Government of Canada, 2018).

Currently, individuals can be partnered with a service-dog through a non-profit, for-profit, train a dog on their own or work with individual trainers, leaving much room for problematic variability. Standardized certification where everyone would be required to go through a universal public access test is one pragmatic step forward. Having universal testing will provide a common benchmark no matter where the service-dog was originally trained. Lastly, while the UK has service-dog oversight mechanisms in place with dedicated animal welfare officers (Hearing Dogs for Deaf People, 2017), Canada does not. This represents a dangerous gap in service-dog policy and implementation, leaving some service-dogs’ wellbeing in peril.

The Societal Need for Respect and Acceptance

While it is critical that those directly involved with service-dog dyads embrace dyadic- belonging, deep and sustainable social change cannot occur in exclusion of the general public. We all need to embrace this dyad, supporting its healthy enactment and ensuring we collaboratively protect the rights of both partners. We must be self-reflective regarding our own biased assumptions about people with disabilities and about disability itself. The denouncement of service-dog dyads or the pitying of the supposed “poor things” are equally damaging. And further, we must call into question speciesist assumptions that justify privileging human needs over nonhuman animals.

Above All Else, Do no Harm

The pairing of trained dogs to improve the quality of life of humans is an increasing social venture and thus requires sober deliberation. Supporting the provision of service-dogs must not inadvertently reinforce ableist dependency myths about disabled people, should not enslave dogs nor define them based on their supposed use-value, nor should this arrangement recuse the state from its’ role in eliminating the barriers in the first place. In addition to the suggestions provided throughout this paper, two further recommendations are necessary.

The Precautionary Principle

Some may argue that there is no proof that participating in a service-dog dyad is beneficial. The fact is that there has been little interest, if any, in exploring that very question. Why is that? Why are we only focusing on the humans who are the presumed beneficiaries of these arrangements? Until we can adequately state that such a pairing is beneficent to the dog also, i.e. articulate the ways in which participation in a service-dog role is good, helpful, or enjoyable for a dog, we must ensure at the very least that it is not maleficent. The precautionary principle is critical in this regard.

The Dalai Lama once stated, “our prime purpose in this life is to help others, and if you can’t help them at least don’t harm them” (Wellbeing World, 2016, para.68). While in the process of more robust research and policy endeavours, the precautionary principle, i.e. “measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically” (Kriebel et al., 2001) should stand as the guiding method with which to address the rights and welfare of service-dogs. While we explore issues regarding the dog’s welfare and working conditions more closely, we must make every effort to prevent harm. As it appears that the implementation of national standards may take many more years despite the urgency, adherence to the precautionary principle will serve as a stop-gap measure. The Five Freedoms of Animals, put forth by the UK’s Farm Animal Welfare Council (2009) must guide the minimal protection of service-dogs. See Table 2.0.

| 1. Freedom from hunger and thirst |

| 2. Freedom from discomfort |

| 3. Freedom from pain, injury, or disease |

| 4. Freedom to express normal behaviour |

| 5. Freedom from fear and distress |

Table 2.0 The Five Freedoms of Animals (FAWC, 2009)

A Requisite Shift in Language

Lastly, is the fundamental need to shift hegemonic language used when referring to service-dogs. Defining and labelling the canine partner based upon his human-centered value and role, reinforces use-value narratives and obliterates his intrinsic value. He is a dog, first and he has been asked to support a human, second. He is a partner. Another shift in language that is long overdue is the troubling use of language that implies human ownership of nonhuman animals, i.e. “He owns 3 cats”, or “her service-dog is so cute”. Using any language that implies owning an nonhuman animal throughout legislation should be removed in order to promote a society where living things are not something to be owned, but an equal member of a team with mutual benefit. As philosopher Merleau-Ponty stated, “the relation of the human and animality is not a hierarchical relation, but lateral, and overcoming that does not abolish kinship” (as cited in Oliver, 2017). Lastly, and perhaps most poignant, is shifting ableist language used in the entire situation concerning the provision of service-dogs. Rather than defining persons by their supposed shortcoming or non-normative features, let us use the language of human companion or partner. Let us invoke the ethos of dyadic-belonging in the very adjectives and nouns used to describe the pairing.

Obligatory Areas to Explore

In this beginning analysis of service-dog dyads, many vital questions have emerged. The questions found in Table 3.0 are intended to deepen the discussion surrounding the enactment of rights-based dyadic-belonging for service-dog partnerships.

|

Conclusion

In Beasts of Burden, Taylor (2017) argues that,

It is essential that we examine the shared systems and ideologies that oppress both disabled humans and nonhuman animals, because ableism perpetuates animal oppression in more areas than just linguistic. Indeed, ableism is intimately entangled in speciesism, and is deeply relevant to thinking about the ways nonhuman animals are judged, categorized, and exploited. (p.71)

Nowhere does the sentiment in this passage ring more true, than within a service-dog dyad grounded in belonging and mattering. Although both have different ways of being in the world, their shared experience of systemic oppression that positions them as “less than” is where their power comes from. Despite some calls for the liberation of service-dogs, we instead have called for a reframing of this relationship through dyadic-belonging. As exemplified by the lead author’s relationship with her canine partner Barkley, service-dog dyads can be mutually rights-respecting. Along with ensuring that the emancipation of one does not come at the cost of another, dyadic-belonging embraces the necessity of reciprocity and mutuality within an egalitarian relationship between partners; something that will only further benefit from our call for national standardization and policy. Although society stresses normality with defined expectations of how one is supposed to live, what is so beautiful about service-dog dyads is their opposition to societal expectations of what “must be”. Each service-dog and human partner has a relationship that is all their own, something that another team could never replicate. Through the enactment of dyadic-belonging, all teams will share the most important commonality: harmony and respect at both ends of the leash.

References

- Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, Statues of Ontario (2005, c-11). Retrieved from the Government of Ontario Website: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/05a11.

- Belonging. (2019). In Merriam-Webster’s dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.merriam- webster.com/dictionary/belonging.

- Benedek, D.M., Fullerton, C. & Ursano, R.J. (2007). First Responders: Mental Health Consequences of Natural and Human-Made Disasters for Public Health and Public Safety Workers. Annual Review of Public Health, 28, 55-68.

- Blunden, A. (2008). Use-Value. Retrieved from https://www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/u/s. htm#use-value.

- Bryant, T.L. (2007). Similarity or Difference as a Basis for Justice: Must Animals Be Like Humans to be Legally Protected from Humans? Law and Contemporary Problems, 70, 207-254.

- Clothier, S. (2005). Bones Would Rain From the Sky: Deepening Our Relationships with Dogs. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

- Coulter, K. (2016). Animals, Work, and the Promise of Interspecies Solidarity. New York: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Coulter, K. (2017). Humane Jobs: A Political Economic Vision for Interspecies Solidarity and Human-Animal Wellbeing. Politics and Animals, 3, 31-41.

- Dale, S. (2014). Assistance Dogs May Be Well Cared For, But Are They Happy? Retrieved from: https://stevedalepetworld.com/assistance-dogs-may-be-well-cared-for-but-are-they- happy/.

- Donovan, J. (2017). Feminism and the Treatment of Animals: From Care to Dialogue. In S.J. Armstrong & R.G. Botzler., The Animal Ethics Reader: Third Edition (42-49). New York: Routledge.

- Farm Animal Welfare Council UK. (2009). Farm Animal Welfare in Great Britain: Past, Present and Future. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/ system/uploads/attachment_data/file/319292/Farm_Animal_Welfare_in_Great_Britain_-_Past__Present_and_Future.pdf.

- Dhamoon, R. (2009). Identity/Difference Politics: How Difference is Produced and Why It Matters. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Eddy, J., Hart, L.A. & Boltz, R.P. (1988). The effects of service-dogs on social acknowledgements of people in wheelchairs. Journal of Psychology, 122(1), 39-45.

- Evans, N., & Gray, C. (2011). The Practice and Ethics of Animal-Assisted Therapy with Children and Young People: Is It Enough that We Don’t Eat Our Co-Workers? The British Journal of Social Work, 42(4), 600-617.

- Fudge, E. (2008). Pets (The Art of Living). New York: Routledge.

- Government of British Columbia. (2015). Guide and Service-Dog Act. Retrieved from http://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/lc/statreg/15017.

- Government of Canada. (2018). April 2018 update on Canadian General Standards Board technical committee on service-dogs. Retrieved from https://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/ongc-cgsb/2018_04_20-eng.html.

- Government of Canada. (2018). Medical Expense Tax Credit-Service Animals. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/programs/about-canada-revenue-agency- cra/federal-government-budgets/budget-2018-equality-growth-strong-middle- class/medical-expenses-tax-credit.html.

- Grossman, E. (2014). An Interview with Sunaura Taylor. Journal for Critical Animal Studies, 12(2), 9-16.

- Gruen, L. (2015). Entangled Empathy: An Alternative Ethic for Our Relationship with Animals. New York: Lantern Books.

- Hall, K. (2014). Creating a Sense of Belonging. Retrieved from: https://www.psychologytoday. com/blog/pieces-mind/201403/create-sense-belonging.

- Hearing Dogs for Deaf People. (2017). HDTV Episode 10: A Warm Welcome from our Welfare Team. Retrieved from https://www.hearingdogs.org.uk/hearing-dogs-tv/hdtv-episode-10-welcome-to-welfare/.

- Henderson, A. (2001). Emotional labor and nursing: an under-appreciated aspect of caring work. Nursing Inquiry, 8(2), 130-138.

- Hens, K. (2009). Ethical Responsibilities Towards Dogs: An Inquiry into the Dog-Human Relationship. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 22(1), 3-4.

- Hopper, T. (2018). ‘They’re s---ing all over’: Scenes from a world taken over by fake service animals. Retrieved from https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/theyre-s-ing-all-over-scenes-from-a-world-taken-over-by-fake-service-animals.

- Hribal, J. (2003). “Animals are a part of the working class”: A Challenge to Labor History. Labor History, 44(4), 435-453.

- Kim, C.J. (2015). Dangerous Crossings: Race, Species, and Nature in a Multicultural Age. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriebel, D., Tickner, J., Epstein, P., Lemons, J., Levins, R., Loechler, E., Quinn, M., Rudel, R., Schettler, T. and Stoto, M. (2001). The Precautionary Principle in Environmental Science. Environmental Health Perspectives, 109(9), 871-876.

- Kwong, M.J. & Bartholomew, K. (2011). “Not just a dog”: an attachment perspective on relationships with assistance dogs. Attachment & Human Development, 13(5), 421-436.

- Lloyd, C., King, R. & Chenoweth, L. (2002). Social work, stress and burnout: A review. Journal of Mental Health, 11(3), 255-265.

- Lorde, A. (2007). Sister Outsider: Essays & Speeches by Audre Lorde. Berkeley: Crossing Press.

- Matsuoka, A. & Sorenson, J. (2014). Social Justice beyond Human Beings: Trans-Species Social Justice. In T. Ryan., Animals in Social Work: Why and How They Matter (64-79). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Meekosha, H. & Shuttleworth, R. (2009). What’s so ‘critical’ about critical disability studies? Australian Journal of Human Rights, 15(1), 47-75.

- Modlin, S.J. (2012). Service-Dogs as Interventions: State of the Science. Rehabilitation Nursing, 25(6), 212-219.

- Nibert, D. (2008). Humans and Other Animals: Sociology’s Moral and Intellectual Challenge. In C.P. Flynn, Social Creatures: A Human and Animal Studies Reader (259-272). New York: Lantern Books.

- Nocella, A.J., Sorenson, J., Socha, K., & Matsuoka, A. (2014). Defining Critical animal studies: An Intersectional Social Justice Approach for Liberation. New York: Peter Lang

- Oliver, K. (2007). Stopping the Anthropological Machine. PhaenEx, 2(2), 1-23.

- O’Neill, O. (1997). Environmental Values, Anthropocentrism and Speciesism. Environmental Values, 6(2), 127-142.

- Payne, E., Bennett, P.C. & McGreevy, P.D. (2015). Current perspectives on attachment and bonding in the dog-human dyad. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 24(8), 71-79.

- Pleasance, C. (2013). Police dogs to get pension plan: Animals to be given £1,500 each to help pay medical bills after they retire. Retrieved from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/ news/article-2487540/Police-dogs-pension-plan-Animals-given-1-500-help-pay-medical-bills-retire-service.html.

- Poiriern, N. (2016). Animal Science, Animal Studies, and Critical animal studies—What’s the Difference? Retrieved from https://blogs.canisius.edu/graduate/author/nathan-poirier/.

- Prince Edward Island Human Rights Act, Statues of Prince Edward Island (1988, H-12). Retrieved from the Government of Prince Edward Island Website: www.gov.pe. ca/law/statues/pdf/h-12.pdf.

- Regan, T. (2001). Defending Animal Rights. Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- Reaume, G. (2014). Understanding Critical disability studies. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186(16), 1248-1249.

- Rollin, B. (1981). Animal Rights and Human Morality. Buffalo: Prometheus Books.

- Saskatchewan Human Rights Act, Statues of Saskatchewan (2011, c-17). Retrieved from the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission Website: http://www.qp.gov.sk.ca/ documents/english/statutes/statutes/s24-1.pdf.

- Simmel, G. (1950). The Sociology of Georg Simmel. New York: The Free Press.

- Social Contract. (2019). In Merriam-Webster’s dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/social%20contract?utm_campaign=sd&utm_medium=serp&utmsource=isonld.

- Swann, W.J. (2006). Improving the welfare of working animals in developing countries. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 100(1-2), 148-151.

- Taylor, N. (2013). Humans, Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-Animal Studies. Virginia: Lantern Books.

- Taylor, S. (2013). Animals, ableism, activism. Journal of Visual Art Practice, 12(3), 235-244.

- Taylor, S. (2017). Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation. New York: The New Press.

- Taylor, S. (2004). The Right to Not Work: Power and Disability. Monthly Review: An Independent Socialist Magazine. Retrieved from https://monthlyreview.org/2004/ 03/01/the-right-not-to-work-power-and-disability/.

- U.S. Department of Justice. (2011). ADA Requirements: Service Animals. Retrieved from https://www.ada.gov/service_animals_2010.htm.

- Valentine, D.P., Kiddoo, M. & LaFleur, B. (1993). Psychosocial implications of service-dog ownership for people who have mobility or hearing impairments. Social Work in Health Care, 19(1), 109-125.

- Vegan Feminist Network. (2015). A Feminist Critique of “Service” Dogs. Retrieved from: http://veganfeministnetwork.com/a-feminist-critique-of-service-dogs/.

- Vehmas, S. & Watson, N. (2014). Moral wrongs, disadvantages, and disability: a critique of critical disability studies. Disability & Society, 29(4), 638-650.

- Wellbeing World. (2016). Inspirational Quotes for Life. Retrieved from http://www.Wellbeing worldonline.com/articles/cat/Inspirational-Quotes/post/Inspirational-Quotes-for-Life/.

- Wenthold, N. & Savage, T.A. (2007). Ethical issues with service animals. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 14(2), 68-74.

- Whitmarsh, L. (2005). The Benefits of Guide Dog Ownership. Visual Impairment Research, 7(1), 27-42.

- Wirth, K.E. & Rein, D.B. (2008). The Economic Costs and Benefits of Dog Guides for the Blind. Ophthalmic Epidemiology, (15), 92-98.

- Withers, A.J. (2012). Disability Politics & Theory. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

- Yount, R.A., Olmert, M.D. & Lee, M.R. (2012). Service dog training program for treatment of posttraumatic stress in service members.

- Zamir, T. (2006). The Moral Basis of Animal-Assisted Therapy. Society & Animals, 14(2), 179- 199.