Tensions of trans-institutionalization in disabled childhoods: A photo essay

Kathryn Church, PhD

Associate Professor, School of Disability Studies

Ryerson University

k3church [at] ryerson [dot] ca

Jessica Vostermans, PhD

Assistant Professor, Critical Disability Studies

York University

jesscort [at] edu [dot] yorku [dot] ca

Kathryn Underwood, PhD

Professor, School of Early Childhood Studies

Ryerson University

jkunderwood [at] ryerson [dot] ca

AbstractThis article describes how researchers from a longitudinal study of early childhood service systems generated a visual representation of transinstitutionalization that could facilitate dialogue for change with a variety of audiences. Comprised of seven portable banners, the photo essay that we constructed features snapshots of documents and/or material objects brought forward by mothers, grandmothers, fathers and foster parents in the course of research interviews. Working the theme of tensions in disabled childhoods, we assembled the collection to produce sharp contrasts between the generalizing effects that institutional involvement has on disabled children, and the particular lives that they live out at home with family members. Proceeding banner by banner, the article reveals the “thinking through” that we did to produce the photo essay, and our hopes for informing action on a systemic relation whereby parents are held responsible for producing ‘normal’ children.

Keywords:Transinsitutionalization, disabled children, childhoods, photography exhibit

Introduction

In framing this special issue, Tobin LeBlanc Haley and Chelsea Jones remind us that institutionalization of Mad, Deaf and/or disabled people is not obsolete or outdated, but remains active through transitions of institutional-style conditions and/or relations to other sites and spaces.[1] Our contribution to this discussion uses a photo essay to highlight key practices in the trans-institutionalization of disabled children in the early years. A product of the Inclusive Early Childhood Service System (IECSS) project, it describes a portable exhibit of themed banners created by the research team to communicate study results beyond the conventional pathways of academic journals or reports. Professionals in practice and government policy makers are potential audiences, but the exhibit is intended, as well, for disability communities and the general public.

The project

The IECSS project is a longitudinal study designed to challenge dominant discourses of early childhood disability, and to create other discourses that are more complex and positive in their understandings of embodied difference.[2] In a framework of mixed methodologies, one line of inquiry draws from Institutional Ethnography, a feminist approach that begins from individual experience to discover and analyze broad relations of governance (e.g. Bisaillon, 2012; Smith & Turner, 2014; Smith, 2005, 2006; Mykhalovskiy & McCoy, 2002; Campbell & Gregor, 2002).

Institutional Ethnography oriented the research team to attend to the power that institutions exert over disabled children even as they take up their own spaces and construct their own identities (Underwood, Frankel, Spalding, & Brophy, 2018; Underwood, Smith, & Martin, 2019). In this empirical and critical tradition, the term ‘institution’ refers not to actual buildings but to ruling “complexes organized around a distinctive function,” such as education, welfare and/or health care (Smith, 2005, p. 225). Against a backdrop of other valuable literature (e.g. Fabris, 2011; Ben-Moshe, Chapman, & Carey, 2014; Burstow, LeFrancoise, & Diamond, 2014; Haley, 2017), our grasp of ‘trans-institutionalization’ aligns with this definition, and the task of analyzing complexes of services that produce ‘disabled childhoods.’

Disabled childhoods are constructed less around individuals’ experiences of bodily difference than they are around encounters with professional assessment and diagnostic identification, often beginning at birth. They are organized around early intervention, family support, cultural and language programs, pre-school and kindergarten programs, and special education (Underwood, 2019). They are permeated with interventions by speech pathologists, occupational therapists, resource consultants, teachers and early childhood educators, doctors, psychiatrists, specialists, and other service providers. They are documented and directed through standardized forms and distinctive discourses activated by professionals in the routine performance of their jobs. Older children experience these relations in schools. For young children, families mediate first contact and front-line engagements with health, early years, therapeutic, and social services.

Study design

Our point of entry into disabled childhoods is the everyday work of families and the recognition that this work is always gendered. We are centrally concerned with the labour that families perform in navigating institutional relations early in the child’s life. Here, we embrace Smith’s ‘generous conception of work’ as “anything that people do that takes time, effort, and intent….what people are actually doing as they participate, in whatever ways in institutional processes” (Smith, 2005, p. 229). Our intent is to study how parents are held responsible for producing ‘normal’ children—and to make visible the work they perform in service of ‘normalcy’ as a concept organizing professional practice across sites (Underwood, Church, & Van Rhijn, in press; Michalko & Titchkosky, 2009; Davis, 1995). Often, this responsibility is actually documented in the standardized forms that guide interactions and mobilize next steps in a child’s life (Smith, 2006; Smith & Turner, 2014).

In Ontario, families can opt in or out of a pre-determined ‘menu’ of services that varies by location. Each option (or its absence) generates work for them. Compliance and refusal are both possible, but each is labour-intensive and complex. Parents and/or caregivers are pulled in and out, this way and that, in negotiations with professionals, services, and systems that are too significant to leave but never fully satisfying (Underwood, Church & Van Rhijn, in press).

By design, the IECSS study facilitates deep and ongoing discussions with families in which they are recognized as active knowers in a “fundamentally interactional event” (Suchman & Jordan, 1990, p. 240-241). The photo essay is informed by these conversations, specifically by interviews with members of 67 families of disabled pre-school children living in five regions in Ontario, including the North. Using open-ended questions, we invited mothers, grandmothers, fathers, and foster parents to comment expansively on situations affecting the disabled children in their lives. As well, we asked them to show us any paperwork or objects they may have acquired that connected their families to early years services.

From closets and cupboards, kitchens, basements, and hasty home offices, participants offered up materials—more and different—than we expected. Certainly there were forms and documents—not just one or two pieces of paper but boxes and boxes—as well as organized collections of documents, filed and bindered documents, documents from doctors, hospitals, assessors, therapists and teachers, faded, ratty documents saved over many years. There were also what we choose to call ‘tender objects’: scissor and glue crafts brought home from school, mementos of prideful moments, soft toys offered by strangers with love or for comfort. Arising naturally through face-to-face exchange, they were unexpected but welcome. We used a digital camera to photograph these objects. The collection we built in this way opened up the possibilities for visual representation.

The Photos

Having assembled hundreds of photos and the stories associated with them, we paused to review and reflect on the whole collection with its mix of documents and other objects. Which images in particular jumped out at us? Why? What were our reasons for gravitating to one image over another? How had participants storied the texts/objects in the interviews? Did certain photos fit together? If so, how? How might they represent disabled childhoods to families? To other audiences? And most significantly for this project, what institutions and professional practices are implicated by the texts/objects in the photos?

As we shifted from collecting to assembling, quite deliberately, we selected photo images that conjured the powerful tensions that characterize disabled childhoods: between the institutional record of diagnostic, therapeutic planning, referral, and service agreement texts and the tender objects of children in the context of home; between the ruling accomplished by medical/professional interventions and the colourful, creative, off-beat interruptions of that ruling which co-exist like a jumble of red, green and yellow magnetic letters stuck to the fridge door.

While each of the images mattered, we were interested, primarily, in creating sharp contrasts between the generalizing effects of contact with and across institutions, and the particular lives of disabled children at home with family members (Smith, 2005). Through these selections and juxtapositions, we crafted a representation of families who are caught in the tensions of disabled childhood: relating to institutional systems not just by acquiescing to the order of things but also by resisting.

The banners

Titled Tensions in Disabled Childhoods, the photo essay comprises seven fabric banners that are unified through the use of a green/blue colour combination (Greenwood, Jack, & Haylock, 2018). Roughly six feet high and two feet wide, each banner stands independently on an adjustable metal platform. Its portability allows for assembling the exhibit in a range of sites and spaces. We ordered the banners to reflect the narrative arc of our data analysis: childhood, documentation, work, participation, humanity and culture. At the same time, we recognized that other orderings were possible as was using some rather than all banners, depending on curator purposes and audiences.

A title banner introduces the IECSS project, names its partner organizations, and provides contact details. Marked by a single-word title, each banner has two photos, side by side, set off by white borders (one banner has a sole photo). Below the orienting ‘headlines’ are brief paragraphs that communicate what the images mean to families and offer a research interpretation. As always, we focused on how each one illuminates the tensions between institutional constructions of disabled childhoods and disabled children as human beings alive in daily relation to others.

The banners celebrate the material culture and texture of family lives without excluding the spoken words—typically more privileged—that have an impact on both. Yet, the images we selected for each one are not mere illustrations of the text that ‘explains’ them. They are a message in themselves, a parallel representation intended to engage directly our understanding of a problematic. Contrasting the institutional and individual dimensions of experience, they convey the ‘feeling’ we developed for the analysis.

Figure 1: childhood Image description: The image above is a series of 4 boxes. The top box, Box 1, is the title and reads “childhood” in white lettering against a blue-green background. Below on the left is a second box, Box 2, with a piece of white paper with two, small black-inked footprints labelled L. Foot and R. Foot. On the right is Box 3 with a picture of an assessment tool. The tool is made up of 3 columns labelled as performance criteria. The middle column is title “visual performance”. To the left of each line of text is a series of small boxes, some of these boxes are shaded in red or blue and others are left blank. Below, in the 4th and final box, is text which reads: “Childhood is ruled by developmental ‘norms.’ ‘Norms’ feed professional practice. They govern professional actions in early childhood education, care and intervention services. The parents we talked to were troubled by “norms”. They know that learning and human development are embodied experiences”. |

The first banner features a hospital photo of tiny human footprints belonging to a baby who was born early. The prints are the intimate marks of a human life—personal and fully embodied. We paired them with the photo of a record of an Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills (ABLLS). ABLLS is a professional assessment tool—disembodied and objective: just one test in a tall stack that documents ways in which disabled children deviate from norms. The tension between a pictorial capture of a precious embodied human life alongside the starkness of a disembodied testing tool asks the viewer/reader to consider the ways in which the pervasiveness of testing in early childhood disability institutions is producing a specific kind of childhood. As one parent told us:

...it’s very, very detailed how they fill this stuff out. It’s hard to look at. This was her assessment from December and I didn’t agree with all of it. But what they tried to explain to me is it’s not the fact that my daughter may not know all of this; it’s is she going to share? Is she going to communicate? Is she going to participate? I knew my daughter could do more than they said, but if she’s not showing them that, then they don’t know. And then also, it is very, very strict.

Despite the unease they create, records such as these are also crucial for families in their attempts to access resources for their children. Parents are troubled by the ways embodied experiences are severed from their context and reduced to norms and troubled, as well, by the need for documents that act as ‘the ticket’ to entry into disability services.

Figure 2: documentation Image description: The image above is a series of 4 boxes. The top box, Box 1, is the title and reads “documentation” in white lettering against a blue background. Below on the left is a second box, Box 2, with a picture of a white piece of paper with a bulleted list that reads: “lack of shared interest and enjoyment, lack of appropriate gaze, lack of response to name, lack of response to contextual clues, lack of communicative utterances or sounds, lack of pointing. Underneath partial sentences are visible. The text reads “the total number of correct responses in a test. This can be converted into a ...ndard score between 85 and 115 are considered average for a child’s age…on a test with a group of children of similar age. Percentile ranks between”. On the right is Box 3 with a picture of a stack of cream colour papers that are duplicates of handwritten notes on papers with the name of an organization written at the top. Below, in the 4th and final box, is text which reads: “Institutions thrive on documents: human beings thrive on connection. To be a disabled child is to be continuously documented. But documentation separates “conditions” from whole lives; it fosters disembodied decision-making. The medicalized and normative language used masks the child as an active member of family, community and programs.” |

We chose these images to stir viewers/readers into pondering the practice of documentation and its purposes in services/institutions. With its damning repetition of the word ‘lack’, the diagnostic assessment on the left constructs the child through a deficit-based set of criteria. Said the parent:

What would happen if you started showing people full pages and descriptions of what your child is not doing? What would happen? If they are scared to hear about allergies when they read all that they will never want to take my child.

This parent is asking how early childhood educators welcome a disabled child if the introduction records only the ways the child is not doing things ‘right’—or if some things are recorded while other things are overlooked. S/he questions assessment in relation to the life of the child as a whole, a life connected to social worlds. Meanwhile, the image on the right captures the layers of documentation created by a resource consultant who visits a childcare centre on a regular basis. It suggests the possibility of time spent with the child who is recorded on these pages. Unfortunately, relational records such as this do not have the same kind of power as that held by diagnostic records.

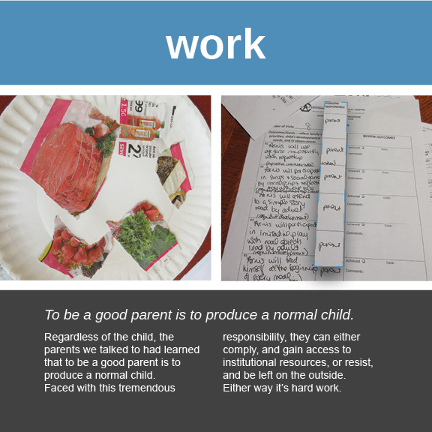

Figure 3: work Image description: The image above is a series of 4 boxes. The top box, Box 1, is the title and reads “work” in white lettering against a light blue background. Below on the left is a second box, Box 2, with a paper plate with pictures of food cut out and arranged on it. On the right is Box 3 which is a piece of paper with a table made up of three columns and 5 rows with handwriting in the left and middle row. The first column is titled, “Outcomes/Goals – Reflects family’s priorities, developmental needs, and EI observations”. Handwritten notes are visible in this column. The second column is title, “Persons responsible”. The text in the middle row is raised for emphasis, and all of the boxes in this column have the word “parent” handwritten below. The third column is titled, “review outcomes” and is blank. Below, in the 4th and final box, is text which reads: “To be a good parent is to produce a normal child. Regardless of the child, the parents we talked to had learned that to be a good parent is to produce a normal child. Faced with this tremendous responsibility, they can either comply and gain access to institutional resources, or resist , and be left on the outside. Either way it's hard work”. |

Our intent with these images is to highlight the labour assigned to parents of disabled children in the world of disability services. In the image on the right, a professional lesson plan lists ‘the parent’ as responsible for all developmental outcomes in a standardized framework of ‘normal’ development. This single image conveys the entire relationship. As one parent queried:

Who’s going to do all this stuff? I mean maybe some women can manage, but I already feel like my [other] daughter is abandoned because of all of this. I don’t even have five or ten minutes to spend with her because I am so busy with all this. So much time and effort; everything goes towards this.

We paired it with an image that we call, fondly, ‘meat on a plate’: a funky assemblage of roast beef and veggie ads glued to paper dinnerware. Familiar to many parental collections, this artful child’s construction both illustrates and escapes the checklist injunction to “participate in imitative play with real objects led by an adult.” It plays with or resists activity lists that are laced with professional interactions and the hard work of meeting institutional expectations. The ‘meat on a plate’ sits alongside the photo representation of lists of labour assigned to parents of disabled children. It asks viewers/readers to think about the many ways that institutions assign labour to parents who are already engaged in the significant reproductive labour of early childhood. Parents of disabled children are asked to do significant amounts of labour by institutions, in specific ways, at specific times, for outcomes dictated by institutions. This banner brings the labour of families living with disabled children and experiencing trans-institutionalization to the forefront, placing the two ‘kinds’ of labour together for discussion of how they are lived out.

Figure 4: participation Image Description: The image above is a series of 4 boxes. The top box, Box 1, is the title and reads “participation” in white lettering against a blue-green background. Below on the left is a second box, Box 2, with the text “that people are happy for [disabled children] and proud of them. And they are proud of themselves”. On the right is Box 3 with a picture of 2 triathlon participation medals with the words swim, bike and run on them. The medal on the left is in a circle, the medal on the right is a square. Both have images of cyclists, runners and swimmers. Below, in the 4th and final box, is text which reads: “Hey! Look what I did! Institutions often used the stories of disabled children to market their services. The ‘supercrip’ narratives of this kind of promotion are challenging - and can be challenged. We discovered resistance in the medals that a disabled child was given for a triathlon. Not as a superhero. Simply a participant”. |

Cast in bright red, yellow and purple, the medals pictured in this single photo celebrate a child’s participation in sporting competitions (TRI KIDS: swim bike run!). Brought forward with pride, they are not the winning medals of a champion, but signify, instead, a child’s participation in the regular experiences of sport and socialization. For the parent, this medal represented “that people are happy for [disabled children] and proud of them. And they are proud of themselves.” That this child was recognized in a meaningful way is a significant contrast to many medicalised childhood disability campaigns. For us, the tension lies in our knowledge of the ‘supercrip’ imagery which is broadly used to represent disabled children—and thoroughly critiqued by disability studies scholars (Grue, 2015; Howe, 2011; Kama, 2004). The ways that trans-institutionalization impacts children is in many ways through their participation in the everyday life of their early childhood. The previous banners on documentation and work tell us the story of ways in which disabled children do not participate in activities their non-disabled peers are engaged in because of the work imposed on them from institutions. The testing, assessing, rehabilitating, speech therapy, and occupational therapy all take up time that is taken away from activities such as assembling a simple craft like ‘meat on a plate’—typical early childhood activities that children participate in. This banner asks the viewer/reader to contemplate the ways disabled children’s participation is shaped through engagement with institutions.

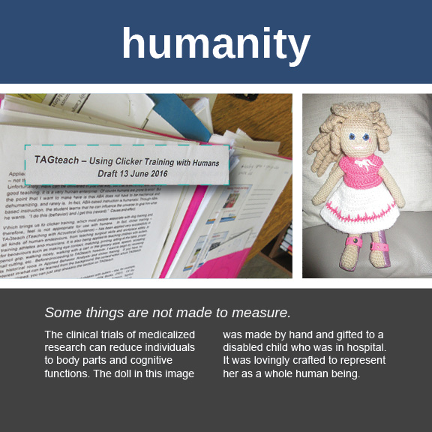

Figure 5: humanity Image description: The image above is a series of 4 boxes. The top box, Box 1, is the title and reads “humanity” in white lettering against a blue background. Below on the left is a second box, Box 2, with a pink file folder full of papers. At the top a super imposed title reading “TAGteach-Using Clicker Training with Humans Draft 13 June 2016”. Box 3, one the right, is a picture of a child’s knit doll with curly yellow hair, a pink and white dress and pink and purple braces on the legs. Below, in the 4th and final box, is text which reads: “Some things are not made to measure. The clinical trials of medicalized research can reduce individuals to body parts and cognitive functions. The doll in this image was made by hand and gifted to a disabled child who was in hospital. It was lovingly crafted to represent her as a whole human being”. |

This banner presents one of the deepest tensions of trans-institutionalization. On the right is the photo of a crocheted doll complete with a leg brace. This object occupies a special place in the heart of one family. Our message hinges on juxtaposing its soft pinkness with the photo of something much darker: an information brochure about ‘clicker training’ as a behaviour modification technique developed for dogs. The doll was lovingly made by someone who perceived a disabled child as a whole being. The pamphlet asserts that clicker training can be very successfully applied to “teaching children with autism behaviors such as making eye contact…. walking nicely…. walking by the cart in a grocery store.” Together they encourage readers/viewers to contemplate the tension between the humanity of children and medicalised practices that reduce them to functions and trainable behavioural impulses. The photo of the ‘clicker training’ is perhaps the most uncomfortable of the series, and was intentionally paired with a photo of the most elementary of childhood objects: a doll made in the child’s image. We want viewers/readers to think about how all children can be supported in their journey to becoming and developing, but also how institutions imagine that becoming and developing: ‘clicker training’ as a tool that was provided to parents of a disabled child as an option to support their development. Similar to the first banner on childhood, this banner asks us to think about disabled childhood as produced through trans-institutionalization: What humanity is imagined and nurtured through these processes?

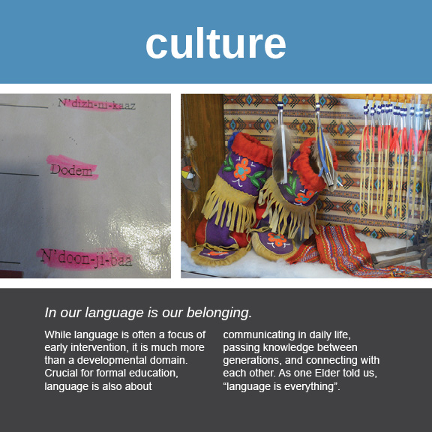

Figure 5: culture Image description: The image above is a series of 4 boxes. The top box, Box 1, is the title and reads “culture” in white lettering against a light blue background. Below on the left is a second box, Box 2, with three Ojibwe words—N’dizh-ni-kaaz, Dodem, and N’Doon-ji-baa—typed on a language worksheet, highlighted in pink. There are blank lines next to the words. On the right is Box 3 with a picture of a display case which shows examples of Algonquin and Métis artwork. Below, in the 4th and final box, is text which reads: “In our language is our belonging. While every language is often a focus of early intervention, it is much more than a developmental domain. Crucial for formal education, language is also about communicating in daily life, passing knowledge between generations, and connecting with each other. As one Elder told us, “language is everything”. |

The final banner contrasts Indigenous cultures with institutional cultures with respect to language as a focus in early childhood intervention and care. The photo on the left features a worksheet that incorporates Ojibway words while retaining their institutional location as part of a language program. The photo on the right features cultural art objects that represent Indigenous culture and knowledges in very different ways. As the parents explained:

It is hard as a parent because you have a western view of what the issues are with your child and then you have a traditional perspective on why your children are experiencing these behaviours and health issues and they don’t always match up. It is confusing.

There are conflicts for Indigenous families in working to maintain traditional ways of nurturing and caring for their children while engaging with institutions that mandate services (Ineese-Nash, Bomberry, Underwood, & Hache, 2018). The inclusion of a photo representing dissonance between Indigenous culture and institutional culture is important because the IECSS project includes a significant number of First Nations and Métis families as respondents. Indigenous partners have been integral to the project from the beginning, and importantly, the Ontario First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework notes the importance of first peoples in Canada having input on special education and all educational policy (IECSS, n. d.). This banner asks viewers/readers to contemplate the conceptions of disability in Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives, with the statement from a parent laying out this difficult and often confusing or disorienting tension Indigenous families live when interacting with institutions.

Concluding remarks

This article describes a photo essay that communicates the tensions of trans-institutionalization in disabled childhoods. As Mykhalovskiy and McCoy recommend, we want this portable display of banners, images, and text to be “an active presence in the world (that will) stimulate reflexive community-based practice” (2002, p. 18). In doing the work, we discovered how readily this form lends itself to disrupting conventional narratives of disability in early childhood, and how poignantly it allows us to ‘show’ rather than ‘tell’ trans-institutionalization.

In recent decades, like other interpretive social scientists, disability researchers have tapped the arts and humanities to conceptualize inquiry, to collect and analyze data, and to disseminate results (Lapum, Ruttonsha, Church, Yau, & Matthews David, 2011; Knowles & Cole, 2008). Although experienced with it (Church, Panitch, Frazee, & Livingstone, 2010; Church, 2008), we did not draw from arts-informed research in our use of visual material. Rather, this photo essay is a data-saturated representation connected directly to interview conversations and critical analysis of interview data.

Our concern is for young lives and families that are captured by institutionalization which does not involve confinement or even, in some cases, ‘knots’ of services. Far from elusive, it is observable, traceable, and retrievable by studying the standardized forms and distinctive discourses of professional practice. Caught up in a net of externalized definitions, the child is moving into and through social institutions—but not just that. Those institutions are also moving into and through the child. The photo exhibit is intended to convey those relations.

The research team is engaged, currently, in displaying the banners for interested audiences, particularly within the service system. So far we have assembled the exhibit in education and rehabilitation sites. It resonates with viewers whether they are disabled people, government policy makers, clinical staff, or families. They are familiar with the tensions it references. The question of the moment is whether a representation such as this can stimulate institutional change.

Endnotes

1. With gratitude, the authors acknowledge the skillful and patient guidance of guest editors Haley and Jones, and the editors of the journal itself. We thank the people who reviewed our manuscript; it benefited immensely from your detailed reading and feedback.2. The Inclusive Early Childhood Service System Project is a partnership that spans 10 geographic areas: the County of Wellington (Ontario), District of Timiskaming (Ontario), City of Hamilton (Ontario), City of Toronto (Ontario), Constance Lake First Nation/Hearst (Ontario), Brandon (Manitoba), Comox Valley (British Columbia), Yellowknife (NWT), Peel Region (Ontario), and Halifax (NS). The project is funded by SSHRC through a Partnership Grant. For information on the study, partner organizations, and publications, visit http://www.InclusiveEarlyChildhood.ca.

References

- Bisaillon, L. (2010). An analytic glossary to social inquiry using institutional and political activist ethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(5), 607-627.

- Ben-Moshe, L., Chapman, C., & Carey, A.C. (Eds.). (2014). Disability incarcerated: Imprisonment and disability in the United States and Canada. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burstow, B., LeFrançois, B. A., & Diamond, S. (Eds.). (2014). Psychiatry disrupted: Theorizing resistance and crafting (r)evolution. Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Campbell, M. L., & Gregor, F. (2002). Mapping social relations: A primer in doing institutional ethnography. Aurora, Canada: Garamond Press.

- Church, K., Panitch, M., Frazee, C., & Livingstone, P. (2010). ‘Out from under’: A brief history of everything. In R. Sandell, J. Dodd & R. Garland-Thomson (Eds). Re-presenting disability: Activism and agency in the museum (pp. 197-212). New York, NY: Routledge.

- A. Cole (Eds). Handbook of the arts in qualitative social science research (pp. 421-434). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Davis, L. J. (1995). Enforcing normalcy: Disability, deafness and the body. New York, NY: Verso.

- Fabris, E. (2011). Tranquil prisons. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- Greenwood, M., Jack, G., & Haylock, B. (2018). Towards a methodology for analyzing visual rhetoric in corporate reports. Organizational Research Methods, 22(3), 798–827. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118765942

- Grue, J. (2015). The problem of the supercrip: Representation and misrepresentation of disability. In T. Shakespeare (Ed.). Disability research today: International perspectives (pp. 204-218). London, England: Routledge.

- Haley, T. L. (2017). Transinstitutionalization: A feminist political economy analysis of Ontario’s public mental health care system (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). York University, Toronto, Canada.

- Howe, P. D. (2011). Cyborg and supercrip: The Paralympics technology and the (dis)empowerment of disabled athletes. Sociology, 45(5), 868-882.

- Inclusive Early Education Service System. (n. d). First Nations and Métis Perspectives. Retrieved from http://inclusiveearlychildhood.ca/our-research/indigenous-engagement/

- Ineese-Nash, N., Bomberry, Y., Underwood, K., & Hache, A. (2018). Raising a child within Early Childhood Dis-ability Support Systems Shakonehya:ra's ne shakoyen'okon:'a G’chi-gshkewesiwad binoonhyag ᑲᒥᓂᑯᓯᒼ ᑭᑫᑕᓱᐧᐃᓇ ᐊᐧᐊᔕᔥ ᑲᒥᓂᑯᓯᒼ ᑲᐧᐃᔕᑭᑫᑕᑲ: Ga-Miinigoowozid Gikendaagoosowin Awaazigish, Ga-Miinigoowozid Ga-Izhichigetan. ,em>Indigenous Policy Journal, 28(3), 1-14. Retrieved from http://www.indigenouspolicy.org/index.php/ipj/article/view/454

- Kama, A. (2004). Supercrips versus the pitiful handicapped: Reception of disabling images by disabled audience members. Communications, 29(4), 447-66.

- Knowles, G., & Cole, A. (Eds). (2008). A handbook for the arts in qualitative inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.<./lI>

- Lapum, J., Ruttonsha, P., Church, K., Yau, T., & Matthews David, A. (2011). Employing the arts in research as an analytical tool and dissemination method: Interpreting experience through the aesthetic. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(1), 100-115.

- Michalko, R., & Titchkosky, T. (Eds.) (2009). Rethinking normalcy: A Disability Studies reader. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars Press.

- Mykhalovskiy, E., & McCoy, L. (2002). Troubling ruling discourses of health: Using institutional ethnography in community-based research. Critical Public Health, 12(1), 17- 22.

- Smith, D. E. (2005). Institutional ethnography: A sociology for people. Lanham, MD: Alta Mira Press.

- Smith, D. E. (2006). (Ed). Institutional ethnography as practice. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Smith, D. E., & Turner, S. (Eds). (2014). Incorporating texts into institutional ethnographies. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- Suchman, L., & Jordan, B. (1990). Interactional troubles in face-to-face survey interviews. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 85(409), 232-241.

- Underwood, K. (2019). Ein systemisches Verständnis inklusiver Kindheit: Das Projekt, Inclusive Early Childhood Service System` (IECSS). In D. Jahr & R. Kruschel (Eds.), Inklusion in Kanada- Internationale Perspektiven auf heterogenitätssensible Bildung (pp. 314-328). Germany: Beltz Juventa.

- Underwood, K., Smith, A., & Martin, J. (2019). Institutional mapping as a tool for resource consultation. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 17(2), 129-139. doi: 10.1177/1476718X18818205

- Underwood, K., Frankel, E., Spalding, K., & Brophy, K. (2018). Is the right to early intervention being honoured? A study of family experiences with early childhood studies. Canadian Journal of Children’s Rights, 5(1), 56-70. doi: 10.22215/cjcr.v5i1.1226

- Underwood, K., Church, K., & Van Rhijn, T. (2020). Responsible for normal: The contradictory work of families. In S. Winton & G. Parekh (Eds.). Critical perspectives on education policy and schools, families and communities. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.