Persistence, Art and Survival

Elaine Cagulada, MA

PhD Candidate, OISE

University of Toronto

elaine [dot] cagulada [at] ryerson [dot] ca

Abstract

A world of possibility spills from the relation between disability studies and Black Studies. In particular, there are lessons to be gleaned from the Black Arts Movement and Black aesthetic about conjuring the desirable from the undesirable. Artists of the Black Arts Movement beautifully modeled how to disrupt essentialized notions of race, where they found “new inspiration in their African ancestral heritage and imbued their work with their experience as blacks in America” (Hassan, 2011, p. 4). Of these artists, African-American photographer Roy DeCarava was engaged in a version of the Black aesthetic in the early 1960s, where his photography subverted the essentialized African-American subject. My paper explores DeCarava’s work in three ways, namely in how he, (a) approaches art as a site for encounter between the self and subjectivity, (b) engages with the Black aesthetic as survival and communication, and (c) subverts detrimental conceptions of race through embodied acts of listening and what I read as, ‘a persistent hereness.’ I interpret a persistent hereness in DeCarava’s commitment to presenting the unwavering presence of the non-essentialized African-American subject. The communities and moments he captures are here and persistently refuse, then, to disappear. Through my exploration of the Black Arts Movement in my engagement with DeCarava’s work, and specifically through his and Hughes’ (1967) book, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, we are invited to reimagine disability-as-a-problem condition (Titchkosky, 2007) and deafness as an ‘excludable type’ (Hindhede, 2011) differently. In other words, this journey hopes to reveal what the Black Arts Movement and Black aesthetic, through DeCarava, can teach Deaf and disability studies about moving with art as communication, survival, and a persistent hereness, such that different stories might be unleashed from the stories we are already written into.

Keywords:deafness, disability studies, Black Studies, Deaf studies, race, Black art

Essentialized identities ask to be disrupted and interrogated. The Black Arts Movement, which began in the early 1960s, was made possible by the artistic disruption and interrogation of essentialized identities. Harkened by some as “the most effective cultural intervention in the history of black resistance in United States” (Taylor, 2011, p. 63), the Black Arts Movement “encompassed all areas of the arts, including theatre, poetry, dance, photography, art and music” (Forsgren, 2019, p. 63). Artists during the Black Arts Movement beautifully modeled how to disrupt essentialized notions of race, where they found “new inspiration in their African ancestral heritage and imbued their work with their experience as blacks in America” (Hassan, 2011, p. 4). Forsgren (2015) recalls that artists within the Black Arts Movement “advocated a black aesthetic as a means to promote racial solidarity and incite community activism against racist social and institutional practices in the United States and abroad” (p. 136). Of these artists, photographer Roy DeCarava was engaged in a version of the Black aesthetic, where his photography subverted the essentialized African-American subject. According to photographer James Hinton, “DeCarava was the first black man who chose by intent to document the black and human experience in America” (as cited in Rachleff, 1997). Born and raised in Harlem, New York, by his Jamaican mother, DeCarava’s photography was intimately tethered to his experience of Harlem and his community (Stange, 1996). His photography, which always lingered close to home, allowed him to achieve his artistic calling as “the consummate, black aesthetic photographer” (Spriggs, 2010, p. 62). In his proposal for the Guggenheim Fellowship, which he was successfully awarded in 1952, becoming the first African-American photographer to receive the Fellowship, DeCarava says of his art and his closeness to Harlem:

I want to photograph Harlem through the Negro people…I want to show the strength, the wisdom, the dignity of the Negro people. Not the famous and the well known, but the unknown and the unnamed, thus revealing the roots from which spring the greatness of all human beings…I do not want a documentary or sociological statement. I want a creative expression, the kind of penetrating insight and understanding of Negroes which I believe only a Negro photographer can interpret. (Galassi, 1996, p. 19)

With his photography, DeCarava did not intend to make a statement, but rather, “a creative expression.” A fine line appears to linger between ‘statement’ and ‘expression,’ but it is DeCarava’s focused desire to encounter Harlem, as it is encountered through him and his subjectivity, that clarifies the nuances between art as expression and art as statement.

This paper explores DeCarava’s work in three ways, namely in how he, (a) approaches art as a site for encounter between the self and subjectivity, (b) engages with the Black aesthetic as survival and communication, and (c) subverts detrimental conceptions of race through embodied acts of listening and a persistent hereness. Through this exploration of the Black Arts Movement, particularly through DeCarava’s work, and specifically through his and Langston Hughes’ book, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, Deaf and disability studies are invited to reimagine disability-as-a-problem condition (Titchkosky, 2007) and deafness as an “excludable type” in new ways (Hindhede, 2011, p. 180). In other words, this journey will reveal what the Black Arts Movement and Black aesthetic, through DeCarava, can teach Deaf and disability studies about conjuring the desirable from the undesirable. Bringing Black Arts and Deaf and disability studies together to both consider and honour DeCarava’s work can tell us of the work that is already being done within the spaces between disciplines. The analysis here will attend to how conceptions of the ‘human,’ and who gets to be treated as well as portrayed as such, can serve as a point of encounter between disability studies and Black Studies, particularly the Black aesthetic as it is discussed through DeCarava’s work. To trouble the essentialization of the African-American subject, as DeCarava sought to do, is to trouble the essentialization of the human. With DeCarava, we can conceive of the human and the human imaginary differently, and begin to tell different stories about the human — stories that emerge in deep contrast to the stories already told of us through white, aud/ableist normalcy.

Black Arts Movement, Kamoinge Workshop, and Roy DeCarava

Different forms of visual, literary, and performance artwork emerged from the Black Arts Movement, all of which were inspired by a strong desire to unite and share the stories of people of African descent across the world (Hassan, 2011). During the insurgence of the Black Arts Movement in the 1960s, a collective of African-American photographers formed the Kamoinge Workshop. Formed in 1963, the Kamoinge Workshop was established in order “to address the underrepresentation of black photographers in the art world” (Gaskins, 2015, p. 16). Members of the Kamoinge Workshop troubled the fixity of an essentialized racial subject through their photography and explored how each of their personal and collective experiences of race influenced and complicated their art (Duganne, 2006, pp.189-204). This dialogue of personal and collective experiences, which manifested in their photography, led to Kamoinge members retrospectively adopting the term “Black aesthetic” when referring to their work (Duganne, 2006, p. 189). Louis Draper, a member of Kamoinge and previous mentee of DeCarava’s, was “determined to follow DeCarava and the painters Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence in marrying modernism to a black aesthetic, which he understood as having little to do with style and form” (Mason, 2016, para. 6). For DeCarava, the Black aesthetic meant “art that serves the needs of [Black] people” (as cited in Mason, 2016, para. 6).

Known member and previous director of the Kamoinge Workshop, as well as sometimes referred to as the creator of the Black aesthetic in photography, Roy DeCarava believed that Black people brought their philosophies of art as communication with the gods from Africa to America (Miller, 1990, p. 848). According to DeCarava, this African genealogy of art as a way of spiritual and mythical being-in-the-world is carried forward in the Black aesthetic (Miller, 1990). Regarding the Black aesthetic’s situatedness in African spirituality, DeCarava offers a distinction between the White and Black artist, where the White artist pursues art that “deals with matters of form, matters of tonality, matters of shape” and the Black artist pursues art as a form of “[grappling] with staying alive, with feeling alien in a society that barely tolerates him…thinking more in terms of integrated ideas about humanity, about communicating to others” (Miller, 1990, p. 848). This perception of art as a form of communication is held above art as a formal engagement, at least in the Black aesthetic, and appears to guide DeCarava’s philosophy and artwork.

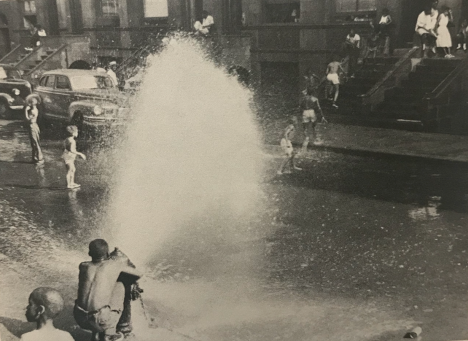

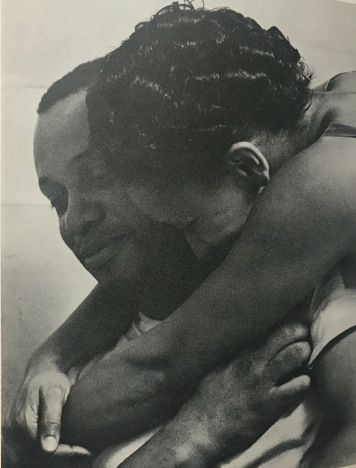

Two stylistic moves are characteristic of DeCarava’s photography — first, he captured “simple, tangible forms” in his photos and second, he relied on a “unified field of light and shadow” (Galassi, 1996, p. 27). He immersed himself in the everyday, “[p]hotographing wherever he found himself, early on, his pictures tracked the places, patterns, and rhythms of movements between job, subway, and home” (DeCarava, 1996, p. 45). That DeCarava’s photography is intensely personal, a form of communication between he and his world, is of interest here when considering how we’ve been taught about listening, hearing, and communication. According to DeCarava (1996), DeCarava’s art “defines a unique sensibility on the part of the photographer toward people… a faith in the perceptions of what he saw and felt” (p. 51). It may be that DeCarava’s unique sensibility, his embodied listening, allowed him to express Black people as “a subject worth of art” (DeCarava, 1996, p. 51). Whether it was children playing in the street (Figure 1) or lovers in an intimate moment of embrace (Figure 2), all of which DeCarava photographed, as Hilton Als (2019) expresses, “is alive the experience of being” (para. 4).

|

Figure 1. Children playing on a street, with a fire hydrant (DeCarava & Hughes, 1967, p. 23). Image description: Pictured in this image, in black and grey tones, are a number of children playing on a street with a fire hydrant. A young child appears to be holding the fire hydrant that is located on one of the sidewalks framing the street. Water sprays out from the hydrant in projectile motion and onto the street. A couple of children play within the splashes of spraying water, shirtless and barefoot. On the other sidewalk, opposite of the child holding the fire hydrant, folks sit and stand on the steps of what appear to be homes lined along this side of the street. Some are watching the children play with the water, while some appear engrossed in other everyday activities. |

|

Figure 2. A couple in embrace (DeCarava & Hughes, 1967, p. 10). Image description: Photographed in black and grey tones, are two people, who appear to be a man and woman, sharing an intimate moment. The woman’s arms are wrapped around the neck of the man. The way the woman is angled toward the man tells us that the woman may be standing, the man sitting. Reaching out to touch the woman, the man’s right hand is gently placed in the space between the woman’s upper left arm and the t-shirt the man is wearing. The woman’s forehead appears to be touching the man’s cheek, face buried in the nook between the man’s neck and the woman’s arms — a nook created by their embrace. Most of the woman’s face is out of view, however, the lines that are visible in their profile, lines around their left eye and along their cheek, indicate that the woman is smiling. |

While DeCarava’s intersubjective approach to his art as communication is intensely personal in its journey into the self, it is also defiant of the idea that black is bad and white is good (Miller, 1990). In his interview with Miller (1990), DeCarava shares, “In a way, that [rebellion against Black as bad and White as good] is part of the Black aesthetic, a conscious defiance of the detrimental dominant values of society” (p. 850). Of his work, he notes: “My work is very spiritual…I take the tangible to present intangible” (Miller, 1990, p. 855). DeCarava’s taking of the tangible to present the intangible emanates what Als (2019) calls “a monumental poetics of blackness” (para. 3). Such a poetics renders an exploration of how race is tied to interpretations of a person’s essence (Als, 2019, para. 3). It would seem, then, that DeCarava’s poetics of blackness can represent a site for encounter between dominant values and reimagined ones; between self and subjectivity; between survival and spirituality— all in the name of a Black aesthetic, where DeCarava arrives and re-arrives at the intangibles in his work.

DeCarava and Hughes’ The Sweet Flypaper of Life

In DeCarava and Hughes’ (1967) book, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, DeCarava’s version of a Black aesthetic as survival and communication is at full force. DeCarava’s photos portray African-American people and communities in various movements and moments, whereas Hughes’ accompanying narrative weaves DeCarava’s snapshots together into a vibrant family story. Challenging the rigidity of dominant singularity, as DeCarava wished to do in his work, there is a sense that there is not one, but at least three different stories present in this text. First, each individual photo shares a story of its own, exposing fragments of DeCarava’s subjectivity and previewing his relationship to the world. Second, the collection of photos as a whole reveals a rawness and realness about DeCarava’s understanding of African-American subjects and communities. The intentional depictions of everyday life in this book align with Duganne’s (2006) observation that members of Kamoinge, such as DeCarava, wished to explore notions of subjectivity in their photography, “beyond generalized notions of African-American identity implied by terms such as ‘black,’ ‘Harlem,’ and ‘insider’” (p. 190). Third, the marriage between DeCarava’s photos and Hughes’ narrative serves as a ‘doubling of’ Black aesthetic. It is as if DeCarava’s African-American subjects are silently persisting, ‘We are Black. We are laughing, crying, playing, dancing, and surviving. We are here.’ This silent persistence of hereness, interpreted here as DeCarava’s commitment to presenting the unwavering presence of the non-essentialized African-American subject, is a refusal to appear essentialized or to disappear altogether. The communities and moments he captures are here and persistently refuse, then, to disappear. This persistence of hereness seems to parallel DeCarava’s own declarations about his work: “I will not go away. I will not be quiet and I will not accept less. I will be heard” (Miller, 1990, p. 853).

The Sweet Flypaper of Life can present, then, as a site for encounter between DeCarava, Hughes, and the subjectivities of the people captured through DeCarava’s own situatedness. Furthermore, the combination of the visual and written form in this book illuminates an encounter of various narratives, just as real and raw as the next story waiting to be released through Hughes or DeCarava’s differing modes of expression. This simple yet complex kind of storytelling in The Sweet Flypaper of Life reflects DeCarava’s method of taking the tangible to represent the intangible in his work. In this book, DeCarava goes further than subverting claims of ‘Black as bad’ into ‘Black as good,’ instead sharing a Black hereness that persists, survives, and calls us into the intangibles of African spirituality.

Deafness, Disability, and Desirability

DeCarava’s persistence of survival, hereness, and intersubjectivity in his Black aesthetic serves as a useful entry point when reimagining disability beyond it being a problem condition (Titchkosky, 2007, p. 38). According to Titchkosky (2007), disability-as-a-problem condition is repeatedly constituted by way of reading, writing, and acting as if embodied differences are ‘natural’ (p. 38). Disability studies interrogates practices, attitudes, and enactments that help constitute disability-as-a-problem and therefore an undesirable ‘thing.’ In part for not wanting to identify as undesirable, some members of the Deaf[1] community have actively rejected the label ‘disabled’ in order to empower themselves as deaf and otherwise fully ‘normal.’ This has paved divides between Deaf and disability studies in that some Deaf scholars and intellectuals have enacted ableism over ‘disabled’ or ‘non-normal’ folk (Robinson, 2010). Despite this history, some scholars argue that deafness and disability arrive in society already interwoven, making it fruitless to cleave one from the other (Rashid, 2010, p. 25).

It is important then, to consider how deaf people face exclusion for being deaf and disabled. Audism, for example, is the belief that one is superior based on hearing ability (Gertz & Bauman, 2016, p. 63). Deaf scholars Gertz and Bauman (2016) distinguish between four forms of audism, one of which being “ideological audism.” Ideological audism is grounded in the belief “that the unique feature of human identity and being is the human ability to use language, where language is defined as speech” (Gertz & Bauman, 2016, p. 63). Such oppressive beliefs are critical to consider, especially when we are confronted with the question of how we constitute the human and who may be afforded to be treated humanely. Additional forms of audism are described by Gertz and Bauman (2016), such as individual, institutional, and dyconscious audism. These varied appearances of audism only draw attention to the complexity of oppression faced by those who do not reach ‘normal’ standards of hearing and oral speaking ability.

According to Hindhede (2011), deaf people uniquely face exclusion from communication, which in turn affects their social interactions. Specifically, she states, “…hearing disability is constructed as a variable that predicts the outcome of specific social interactions” (Hindhede, 2011, p. 181). This analysis aligns with Rashid’s (2010) comparison between being deaf in Nigeria to being Black in America:

For generations, black people with lighter skin generally fared better, because they more closely resembled the white ideal. For deaf Nigerians, advantages have been bestowed on those who are more hard of hearing than deaf, on those who possessed oral speech abilities over those who do not. (p. 24)

In other words, a person’s hearing and oral speech abilities may be perceived as granting them certain advantages or disadvantages in social interactions, similar to how variations in skin colour may be perceived in America. That disability as well as race can be constructed as variables that determine one’s social advantages is reminiscent of racial capitalism, which, “…[accumulates] by displacing the uneven life chances that are inescapably part of capitalist social relations onto fictions of differing human capacities, historically race” (Melamed, 2015, p. 75). Considering how constructions of deafness may be part of fictions of differing human capacities, it might come as no surprise when deafness and disability are named undesirable problem conditions, where uneven life chances and social disadvantage already await deaf and disabled ‘problem people.’ This begs the question, is there a way to reach beyond constructions of deafness as merely a predictive variable of social value? How might we imagine what else deafness can be, is, or has been, other than a problem or disadvantage?

DeCarava’s Embodied Act of Listening

DeCarava’s Black aesthetic can inspire a departure from deafness as an “excludable type” (Hindhede, 2011, p. 180), in that his approach to art troubles scientific notions of our basic ‘human’ senses. When asked about the “theme of listening” in his work, DeCarava shared, “Seeing in the same way one listens. To listen means to concentrate on something that you are listening to” (Miller, 1990, p. 851). Here, DeCarava does not rely on scientific notions of seeing and listening where we are told which body parts permit sight or sound, but instead relies on the act of concentration to help mark the fluidity of our senses. While he may not have intended for this statement to disrupt rigid understandings of the human sensorium, his description of listening inspires reimaginings of deafness beyond its undesirability as a variable that indicates hearing loss and therefore decreased social value.

DeCarava’s theme of listening also unfolds in his work when he engages in an embodied act of listening, where he waits for his subjects to embody an intensity or commitment that moves him. This embodiment of feeling, which inspires DeCarava’s photography, reflects his concept of “sound visualization” (Miller, 1990, p. 851). For DeCarava, there is something remarkable about the intensity that might express itself in the concentrated face of a musician — more remarkable than if a musician was to be simply photographed with an instrument (Miller, 1990). By waiting to be moved and, in turn, feeling that he has been moved by someone else’s intensity, DeCarava engages in an embodied act of listening that depends on his whole body, rather than just his ears or eyes, to interpret meaning. The distinction between listening by ear and embodied acts of listening is important, especially as this paper wishes to glean lessons from DeCarava’s approach to photography for reimagining deafness and disability. That is, one need not remain constrained by scientific notions of hearing but rather, can create beautiful art through embodied acts of listening, which encourages an openness to being moved by others, however that might happen.

In what feels similar to DeCarava’s embodied act of listening, Mintz (2012) describes the installation artwork of Deaf artist, Joseph Grigely, as dramatizations of “human communication as an embodied act,” where Grigely “demotes the ear as the agent of understanding and situates dialogue in a larger narrative that unfolds between people whose whole bodies matter to intersubjective exchange” (p. 1). Such an analysis can work alongside DeCarava’s work where, in The Sweet Flypaper of Life, the ear as an agent of understanding does not ground the possibility for exchange between photographer, subjects, and spectator. Remembering DeCarava’s fluid definition of listening as concentrating, it is arguably the self, not the ear, which acts as an agent of understanding in his work.

Drawing Connections

When endeavouring to reimagine deafness and disability as desirable, DeCarava, the Black aesthetic, and the Black Arts Movement provide key lessons. These key lessons have to do with deaf and disabled people coming together to celebrate their differences, possibly spearheading movements based on self-celebration, and explicitly renaming ‘normalcy’ as ‘white audist/ableist normalcy.’ On the Black Arts Movement, Neal (1968) states: “This sensibility [Euro-American], anti-human in nature, until recently, dominated the psyches of most Black artists and intellectuals; it must be destroyed before the Black creative artist can have a meaningful role in the transformation of society” (p. 32). Therefore, the Black Arts Movement, Neal (1968) argues, is “an ethical movement…from the viewpoint of the oppressed” (p. 32).

In a different manner, deaf and disabled people also have a history of being oppressed by an anti-human sensibility. Garland-Thomson (2009) argues, “To be granted fully human status by normates [people who can represent themselves as definitively human], disabled people must learn to manage relationships from the beginning…[to] use charm, intimidation, ardor, deference, humor, or entertainment to relieve nondisabled people of their discomfort” (p. 69). While there are disabled artists, such as Grigely, who challenge anti-human oppression by engaging in their own persistence of hereness, disability studies can play a greater role in destroying dehumanizing Euro-American sensibilities. Perhaps, there is an ethical movement, influenced by the Black Arts Movement, waiting to be unleashed on behalf of creating space for deaf and disabled people as humans who do not need to relieve nondisabled people of any discomfort caused by their existence.

On the Black aesthetic, Neal (1968) noted that, “The motive behind the Black aesthetic is the destruction of the white thing, the destruction of white ideas, and white ways of looking at the world” (p. 30). Given this motive, the work of DeCarava and other artists engaged in the Black aesthetic offer radical ways of dismantling whiteness as the order that governs the ‘normal’ way of doing things. Deaf and disability studies, then, can learn from the Black aesthetic when attempting to disrupt the ‘normalized’ order that threatens to also essentialize deaf and disabled identities. Ware (2019), in a compelling call to respond to the sharp sense of “unwelcomeness” and “un-belonging” that circulates in “this white supremacist, ableist, trans and queer phobic anti-Black world,” suggests that different approaches to change are needed in our social world (p. 10). Given Ware’s (2019) suggestion that we move to “another space of knowing rooted in Black empowerment and trans, disability, and racial justice” (p. 13), I propose that the Black aesthetic and the work of artists, like DeCarava, be a starting point for our travels into alternate spaces of knowing.

Furthermore, through the Black aesthetic, Deaf and disability studies can continue taking up radical ways of dismantling whiteness in their interrogations of normalcy, so that normalcy is effectively exposed as a ‘white aud/ableist normalcy.’ This is especially important given that Deaf and disability studies have been critiqued for not fully recognizing race (Rashid, 2010). “Disability studies,” according to Pickens (2019), “rarely engages whiteness as a social position and often thinks of Blackness as a contribution rather than part of its construction” (p. 7). She continues, saying, “As long as whiteness remains the normative racial category, investigations of disability that do not address whiteness directly leave open crucial lacunae” (Pickens, 2019, p. 7). Exposing normalcy, then, as a white aud/ableist normalcy, particularly in Deaf and disability studies scholarship and discussions, is one way to fill, if not at least notice, the crucial lacunae that remain wide open when whiteness is left unaddressed in Deaf and disability studies.

In any call to notice and address colonial oppression, however, it is important to remember that these articulations spring from the same world and normalized order we wish to reimagine (Titchkosky, 2015, p. 5). In her exploration of impairment rhetoric and dead metaphors in social justice praxis, Titchkosky (2015) reminds us to engage “abnormality as something other than a call to return to the ordinary and the same” (p. 15). Rather than returning to the ordinary and the same when exposing normalcy as white aud/ableist, we might follow Titchkosky’s (2015) call towards “a non-rhetorical engagement with metaphors of impairment” such that we might “…do something other than draw on the power of medicine and bureaucracy to characterize what is wrong, to diagnose, to contain and control” (p. 15). Through the Black aesthetic, we can more closely attend to how Blackness is already a part of Deaf and disability studies. With DeCarava, we might recognize the ways in which his art represents a non-rhetorical engagement with metaphors of impairment — especially where Euro-American sensibilities (Neal, 1968) have constructed ‘black’ as a metaphor of impairment, perceiving Blackness and “disability as the edge of human life by (re)producing a conception of the human steeped in its own inhumanity” (Titchkosky, 2015, p. 2).

Finally, DeCarava’s teachings for how we perceive deafness and disability abound. His persistence of hereness, survival, and communication inspires a similar persistence in Deaf and disability studies, highlighting what can be done to disrupt anti-human, Euro-American sensibilities. These sensibilities that are “anti-human in nature,” as Neal (1968) tells us, exist in relation to many theories of what it means to live between human and anti-human impulses. There is the post-human, wherein a new epoch of being arises from a disavowal of human (Goodley, Lawthom, & Runswick-Cole, 2014). There is also the production of the non-human — a category, discussed in Wynter (1994)’s exploration of the N. H. I. acronym, that has “genocidal effects with the incarceration and elimination of young Black males by ostensibly normal, and everyday means” (p. 45). Cesaire (1972), too, explores what lives between the human and anti-human, in what he calls “thingification” (p. 42). Those that are thingified are needed for colonization and are “drained of their essence, cultures, trampled underfoot, institutions undermined, lands confiscated, religions smashed, magnificent artistic creations destroyed, extraordinary possibilities wiped out” (Cesaire, 1972, p. 43). Thingification is made only possible through relations of domination and submission — relations grounded in what Cesaire (1972) calls, “no human contact” (p. 42). Anti-human Euro-American sensibilities, traced from these discussions of the human and brought here to us by Neal (1968), may be understood then as moving just beyond that of the post-human, non-human, and thingified human. The anti-human might be perceived as the wretched antithesis to the ideal human, constructed from and reproduced by Euro-American sensibilities. The anti-human is lesser than non¬-human as it is not just that the anti-human is not human but rather, that the anti-human is the human’s depraved sibling— an offense to humanity, related nonetheless.

DeCarava’s approach to capturing the everyday lives of African Americans without subscribing to or reinforcing a generalized African-American identity provides hope for lives plagued by anti-human, and less-than-human, sensibilities. His art further invites us to reimagine disability and deafness as desirable without reinforcing essentialized notions of what it means to be disabled and/or deaf. DeCarava’s theme of listening and sound visualization further gifts new ways of imagining deafness, where listening is not only experienced with one’s ears but rather, is an embodied experience that includes myriad ways of moving through the world. Putting DeCarava and Grigely’s art in conversation, it becomes clear that themes of communication and survival ground their work as artists who have experienced exclusion in some way. Interestingly, both DeCarava and Grigely both work from within their experiences of exclusion, rather than claiming to be outside or above it, and create art that shares different stories about what it means to be Black, deaf, and/or disabled.

Conclusion

DeCarava’s approach to photography presents different ways of responding to essentialized identities — in his case, responding to the essentialized African-American character. From his social, political, and historical position, DeCarava created art that communicated the everyday stories of African Americans without generalizing the ‘African American’ character. In The Sweet Flypaper of Life, African-American people are captured clad in formal clothing, work clothing, or sometimes little to no clothing at all — such as in a photo where a number of children are playing on the street with a fire hydrant exploding with water (DeCarava & Hughes, 1967, p. 23). The expressions in the photos range from bored, excited, downtrodden, happy, carefree, and angry, whereas some expressions are more difficult to name.

An active participant in the worlds he tried to capture, DeCarava successfully presented various African-American characters and communities. His dedication to immersing himself in his work, in the name of exploring himself as well as surviving whiteness, reclaiming Blackness (albeit not a singular Blackness), and persisting on an intangible hereness, teaches Deaf and disability studies about the creative release found in surviving and persisting through narratives of problem conditions and excludable types. In other words, what can be rendered desirable from the undesirable? How can engaging the anti-human sensibilities of white aud/ableist normalcy release new meanings from the stories we are always already written into? How is a persistent intangible hereness of disability and deafness being captured, just as DeCarava captures the intangible hereness of his African-American characters and communities? Just as DeCarava openly expressed being inextricably tied to his art, carrying forward his belief in African spiritual philosophies, one can dream of the art and reimaginings that might emerge from adopting DeCarava’s philosophy of art as a site for self-encounter. The Black Arts Movement and Black aesthetic teaches us that there are different stories and perspectives hoping to be communicated about the relation between deafness, disability, and Blackness, and people ready to receive these new possibilities.

Endnotes

1. The ‘D’ is capitalized here to denote individuals who are members of the Deaf community. The Deaf community has a unique culture, including the use of signed languages (Gertz & Boudreault, 2016, p. xxxii). When encompassing the Deaf community as well as those who do not identify with the Deaf community, a lowercase ‘d’ is used.References

- Als, H. (2019). Roy DeCarava’s poetics of blackness. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/23/roy-decaravas-poetics-of-blackness

- Burch, S., & Kafer, A. (Eds.). (2010). Deaf and disability studies: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Césaire, A. (1972). Discourse on colonialism. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Collins, L. G., & Crawford, M. N. (Eds.). (2006). New thoughts on the Black arts movement. New Jersey, US: Rutgers University Press.

- DeCarava, R., & Hughes, L. (1967). The Sweet Flypaper of Life. New York, US: Hill and Wang.

- DeCarava, S. T. (1996). Pages from a notebook. In P. Galassi, Roy DeCarava: A retrospective (pp. 41-59). The Museum of Modern Art: H. N. Abrams.

- Duganne, E. (2006). Transcending the fixity of race: The Kamoinge Workshop and the question of a “Black Aesthetic” in photography. In L. G. Collins & M. N. Crawford (Eds.), New thoughts on the Black arts movement (pp. 187-209). New Jersey, US: Rutgers University Press.

- Forsgren, L.D.L. (2015). “Set Your Blackness Free”: Barbara Ann Teer’s art and activism during the Black Arts Movement. Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies, 36(1), 136-159. Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/article/576874

- Forsgren, L.D.L. (2019). From the Black Arts Movement to the contemporary Chitlin’ circuit: An Interview with Woodie King Jr. Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism 33(2), 61-80. doi:10.1353/dtc.2019.0004.

- Galassi, P. (1996). Roy DeCarava: A retrospective. The Museum of Modern Art: H.N. Abrams.

- Garland-Thomson, R. (2009). Disability, identity, and representation: An introduction. In T. Titchkosky & R. Michalko (Eds.), Rethinking normalcy (pp. 63-74). Toronto, ON: Canada Scholars’ Press.

- Gaskins, B. (2015). Anthony Barboza in conversation with Bill Gaskins. Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, 37, 16-27. doi:10.1215/10757163-3339827

- Gertz, G., & Bauman, H. L. (2016). Audism. In G. Gertz & P. Boudreault (Eds.), The Sage Deaf Studies encyclopedia (pp. 63-65). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Gertz, G., & Boudreault, P. (Eds.). (2016). The Sage Deaf Studies encyclopedia. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Goodley, D., Lawthom, R., & Runswick cole, K. (2014). Posthuman disability studies. Subjectivity, 7(4), 342-361. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2014.15

- Hassan, S. (2011). Remembering the Black Arts Movement. Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, 29, 4-7. Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/article/480691

- Hindhede, A. L. (2011). Negotiating hearing disability and hearing disabled identities. Health, 16(2). 169-185. doi:10.1177/1363459311403946

- Mason, J. E. (2016). A photographer who captured the complexity of Black life in lyrical ways. Retrieved from https://hyperallergic.com/307286/a-photographer-who-captured-the-complexity-of-black-life-in-lyrical-ways/

- Melamed, J. (2015). Racial capitalism. Critical Ethnic Studies, 1(1), 76-85. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/jcritethnstud.1.1.0076

- Mintz, S. B. (2012). The art of Joseph Grigely: Deafness, conversation, noise. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 6(1), 1-16. doi:10.3828/jlcds.2012.1

- Miller, I. (1990). “If It Hasn’t Been One of Color”: An interview with Roy DeCarava. Callaloo, 13(4). 847-857. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2931378

- Neal, L. (1968). The Black Arts Movement. The Drama Review: TDR, 12(4), 28-39. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1144377

- Pickens, T. A. (2019). Black madness: Mad Blackness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Rachleff, M. (1997). The sounds he saw: The photography of Roy DeCarava. Afterimage, 24, 15–17. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aft&AN=505829595&site=ehost-live

- Rashid, K. (2010). Intersecting reflections. In S. Burch & A. Kafer (Eds.), Deaf and disability studies (pp. 22-30). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Robinson, T. (2010). “We are of a different class”: Ableist rhetoric in Deaf America, 1889-1920. In S. Burch & A. Kafer (Eds.), Deaf and disability studies (pp. 5-21). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Spriggs, E. (2010). Remembering Roy DeCarava’s thru Black eyes. The International Review of African American Art, 23(1), 62. Retrieved from http://gateway.proquest.com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:bsc:&rft_dat=xri:bsc:ft:iibp:357027474

- Stange, M. (1996). "Illusion complete within itself": Roy DeCarava's photography. The Yale Journal of Criticism, 9(1), 63. Retrieved from http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/docview/1300841964?accountid=14771

- Taylor, C. (2011). After the Black Arts Movement. Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 29, 62-71. Retrieved from https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/480697

- Titchkosky, T. (2007). Reading and writing disability differently: The textured life of embodiment. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

- Titchkosky, T. (2015). Life with dead metaphors: Impairment rhetoric in social justice praxis. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 9(1), 1-18. doi:10.3828/jlcds.2015.1

- Ware, S. M. (2019). The most unwelcoming 'Outstanding Welcome': Marginalized communities and museums and contemporary art spaces. Canadian Theatre Review 177, 10-13. doi:10.3138/ctr.177.002

- Wynter, S. (1994). “No Humans Involved: An Open Letter to My Colleagues.” Forum N.H.I, 1(1), 42-73. Retrieved from http://carmenkynard.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/No-Humans-Involved-An-Open-Letter-to-My-Colleagues-by-SYLVIA-WYNTER.pdf

- Titchkosky, T. (2007). Reading and writing disability differently: The textured life of embodiment. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.