Archival Artistry: Exploring Disability Aesthetics in Late Twentieth Century Higher Education

Lauren Beard

The Pennsylvania State University

lbeard2 [at] gmail [dot] com

Abstract

Jay Dolmage’s (2014) Disability Rhetoric encourages scholars to search beyond normative Aristolean bounds of rhetoric and embrace a critical lens of rhetorical activity as embodied, and disability as an inalienable aspect of said embodiment (p. 289). To that end, this project posits an innovative structure for rhetorically (re)analyzing disability history in higher education through a framework of disability aesthetics. In Academic Ableism, Jay Dolmage (2017) argues that an institution’s aesthetic ideologies and architecture denote a rhetorical agenda of ableism. In Disability Aesthetics, Tobin Siebers (2010) asserts disability is a vital aspect of aesthetic interpretation. Both works determine that disability has always held a crucial, critical role in the production and consumption of aestheticism, as it invites able-bodied individuals to consider the dynamic, nonnormative instantiations of the human body as a social, civic issue (p. 2). Disability, therefore, has the power to reinvigorate the sociorhetorical impact of both aesthetic representation and the human experience writ large. With this framework in mind, this project arranges an archival historiography of disability history in higher education in the late twentieth century at a mid-sized U.S. state institution. During this time, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act was finally signed into law, and universities confronted a legal demand to allow all students access. Ultimately, this project seeks to demonstrate how disability scholars and historiographers can widen the view of both disability history and disability rhetoric in higher education through a focus on student aesthetic performance and intervention.

Keywords:Disability, Aesthetics, Art, Ableism, Higher Education, Civil Rights, Disability Rights, Disability History, Disability Rhetoric

Introduction

“I’m literally deaf...and you may detect something odd about my speech. Most people think it’s French, but it’s only a lateral lisp” (Galloway, 1991). When queer and disabled comedian Terry Galloway treaded waggishly onto the School of Dance’s stage at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in 1991, she was met with an audience of students waiting hungrily for her raucous and raunchy jokes about disability. These students invited her to their school because her performance art utilized humor and consubstantiation to empower their disability experiences and validate their pain—for example, making fun of her lisp and others’ misunderstandings of it. Galloway (1991) also told humorous but raw stories of being a failed abortion when her mother found out she would be disabled and also being a “dorky” “deaf kid” covered in hearing-assistance hardware (GlobalVillageVidiot). A student reviewing her visit said everyone was “excited” to see her performance because they “were sure [it] would relate to the experience of living with a disability” (DSS Newsletter, Fall 1991). The author of this review goes on to write, “We found out that Terry Galloway is outspokenly unconventional about the way she thinks about life itself...She is irreverent in the way she talks about her disability, not being careful to use the ‘right,’ ‘politically correct’ words...her work is both ‘funny and grim’ [and students say they] identified with her” (DSS Newsletter, Fall 1991). Instead of being the object of shame and ridicule, Galloway used her experiences as an outsider to become an agent of critique, shaming normate society for their exclusionary biases and ideological and material oppression. These students’ avid welcoming of Galloway emphasized an awareness of the need to challenge the ableist narratives imposed upon them by institutional ideology. As will be explored in this article, the exigence for this desire arose in part from the sociocultural and policy shifts present in the late twentieth century.

Theoretical Framework and Methodology

Historical Context

The zeitgeist of mid-to-late twentieth century United States championed a simple yet radical concept: equality. Just a brief glance at culture during this time reveals a montage of individuals whose names have become synonymous with tireless Civil Rights advocacy, such as Harvey Milk, Ruth Bader Ginsberg, and Martin Luther King Jr. This period of history also witnessed the rise of a sociopolitical entity that was making a powerful Civil Rights statement in mainstream America. Disabled individuals were beginning to cultivate a formidable political identity. Scotch and Barnartt (2001), in their monograph Disability Protests: Contentious Politics 1970-1999, reveal that protests by disabled people and their allies erupted in the 1970s and continued to “flourish” well into the 1990s (pp. 222-223). To quote Kaier’s poem above, they had “broken the old taboo” of being satisfied with, and silent about, government paternalism and sub-par citizenship.

After Section 504 became law and universities could no longer deny access to individuals based on their disability, institutions of higher education across the United States saw a dramatic increase in the numbers of disabled people both applying for college and disclosing their disabilities to their university to receive necessary accommodations.[1] This project’s purpose is to highlight what disability scholars have been theorizing for years (namely, that disabled individuals bring valuable resources, insights, and contributions to the university) by investigating university records to recount how disabled students at one university, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, turned towards aesthetic measures to advocate for their access to, and validity within, higher education. This attention to aesthetics within the institutional archive has the potential to augment historiographic tools of researching and analyzing narratives of disability in higher education.

Theoretical Framework

Jay Dolmage (2017) writes that academia is a moving, performative entity built on both a physical and metaphorical architecture of “steep steps” (p. 2). The physical steep steps are the “stylistic and aesthetic center” of many campuses, leading most often to the library or other scholarly hub (p. 2). Dolmage (2017) theorizes the steps as a sort of spatial metaphor, within which exists a “latent argument about aesthetics or appearances, one that trips over the classroom, into ideology and into pedagogy” where instructors and administrators are “concerned about pattern, clarity, propriety--and these things [that] are believed to be beautiful” (p. 2). In other words, in order to achieve success and be regarded as normal and acceptable in higher education, one must be able to both physically interact with aesthetic architectural barriers (which were decidedly not built with disabilities in mind) as well as metaphorically climb the steep steps of higher education mentally. Educational leaders built the university system in such a way that anyone who does not embody certain privileged ideations of a student cannot easily succeed. These rigid aesthetic standards of uniformity and structure as hallmarks of an acceptable academic atmosphere disguise a deep-seated tradition of “Academic Ableism,” or, an overwhelmingly positive valuing of “able-bodiedness” within the university (Dolmage, 2017, p. 7). By privileging ability as a site of power and correctness, institutions of higher learning normalize what Dolmage (2017) refers to as ableist aesthetics: the exclusionary barriers, both material and ideological, which are built with default able-bodiedness in mind, and are regarded as beautiful, iconic, and correct. Dolmage (2017) argues that academic buildings which students and faculty use every day are “alive,” and thus “an inaccessible building...is alive and working to physically filter students out of the university every single day” (p. 37). Therefore, by looking at the materiality of the campus as a rhetorically living organism, one can begin to see ableist aesthetics as an insidious parasite which creeps its way into the physical and ideological spaces of the campus.

Tobin Siebers (2010) also investigates this concept of aesthetics and what we are “allowed” to call beautiful by exploring the presence of disability in art, especially twentieth century art (p. 1). Siebers (2010) claims that modern art conceptualizes the disabled body as a critical aesthetic form, which is significant because it posits the human body as both the “subject and object of aesthetic representation” (p. 1). Explained another way, when artists position disability within the human body as the focus of a piece of art, the audience must contemplate the human body as a network of simultaneous beauty, unconventionality, strength, and damage. When made public, as these disability student groups made themselves public, these aesthetics force audiences to interact with the fragile, dynamic, nonnormative instantiations of the human body as a social, civic issue (p. 2). Disability, therefore, becomes an indispensable aspect of both aesthetic representation and the social human experience. Siebers (2010) argues this art is significant because it “[returns] aesthetics forcefully to its originary subject matter: the body and its affective sphere” (p. 2). With this point of view in mind, he coins the term “disability aesthetics” to refer to “a critical concept that seeks to emphasize the presence of disability in the tradition of aesthetic representation” (Siebers, 2010, p. 2). By expanding disability in art from a mode of artistic expression to a critical rhetorical concept, Siebers (2010) invites individuals to carefully examine the aesthetic role disabled bodies play in all aspects of society.

The current project combines disability aesthetics with academic ableism under the critical apparatus of disability rhetoric to provide a heuristic for bringing an aesthetic focus to the rhetorical work of amplifying marginalized voices in institutional histories. Dolmage (2014) argues in Disability Rhetoric that “[r]hetoric is always embodied” and it is vital we are aware of “which bodies we align with rhetoric” and which bodies we would rather exclude from the rhetoric tradition or we deem as unable to perform rhetorically (p. 289, 69). Ultimately, he argues for a cripping of the rhetorical tradition—a space for narratives that seep beyond able-bodied Aristolean interpretations of what counts as rhetorical. In the same spirit, I propose a cripping of the institutional archive.

To this end, this project follows the presence of the aesthetic in the archive and demonstrates how it weaves through disability, institutionalism, ideology, and art. By taking Siebers’s (2010) conception of disability’s vital role in aesthetics and in societal conceptions of beautiful and worthy bodies, and overlapping it with a critical investigation into students’ defiance of academic ableism through artful expression, scholars can begin to carve out platforms for these resistive narratives, and piece together historiographies which expose surreptitious oppression and transcend normative notions of embodied rhetorical performance.

Methodology

The history of disability in higher education is a sticky and often painful—but nonetheless deliciously labyrinthine and powerful—narrative. As a researcher who is not formally trained in archival work, the north star I clung to in this study was, as with many other scholars in my same position, a voracious desire to find the hidden stories in the official records. The musty boxes and laminated folders in my university’s archive were meticulously categorized and contained. In boxes labelled “Disability” and “ADA,” I read through chancellor addresses, faculty correspondences, and official ADA inspection reports for hours before happening upon a box inscribed “Disability Student Services.” Upon opening this container, I was met with a gorgeous collection of color, poetry, paintings, and short stories written by students, as well as letters from students demanding to know why the university was refusing to build an accessibility ramp to buildings like the cafeteria or the library, and comic strips addressing outdated ableist tropes. In short, this box, and the folders inside of it, pushed against institutional archival boundaries placed around disability. The table on which sat the dry, official documents I had been looking through was now drowned in a deluge of student activism. Spreading all this material out on my desk, I witnessed a live unfurling of a hopeful, emotive, excitingly unruly mosaic of disabled students’ lived experiences told almost exclusively through art—an atypical account of an atypical student body.

To honor these disability student activists, and to approach this research through a means more reflective of the disruptive nature of non-normate bodies in academia, this current project seeks to illuminate how disabled student voices crip institutional archival histories. I am borrowing this notion of “cripping the archive” from Sarah Brophy and Janice Hladki’s (2014) “cripping the museum.” They argue these non-normative materials in larger archives “come into view as an archive of rebellion, a dissident archive that rubs up against normative ideas about diversity, willfully proposing alternative pedagogical positions and insistently bringing into view the layered discourses and materialities of difference that constitute embodied lives” (p. 331). In this way, records of marginalized bodies within a normative, larger institutional archive “[generate] forms of uncertainty, mobility, and friction that [abrade] the dominant neoliberal model of diversity as recognizable and manageable substance” (Brophy and Hladki, 2014, p. 331). The art pieces and other aesthetic objects in the “Disability Student Services” box seep beyond the generic and limiting bounds of “official” institutional documents, bursting out of their containers and demonstrating the vivid stories of crip life on an “un-cripped” campus (Brophy and Hladki, 2014, p. 331). Thus, these students have preserved an important moment of archival cripping, both in the literal, material forms of the objects as well as in the histories they tell within the larger context of a state-run institution of higher education.

Project Scope and Rationale

This project spans the archive of student-generated and student-centered disability newsletters from 1982-1998, which continually feature art. The reason for these time ranges is both practical and historical. The University’s archives grow richer as one approaches the late 80s and 90s, which corresponds with the emergence of a mainstream political consciousness within the disability community, as well as a growing number of protests and demonstrations.[2] Therefore, while this project does not seek to provide an explicit connection between nation-wide activism and activism on The University of North Carolina at Greensboro’s campus, it does acknowledge a trend in the amount of student-centered advocacy in the archives during this time compared with the rest of the United States. The constraints of this article prevent the case study from moving much outside the bounds of this specific university, as well as limit the extent to which larger disability arts and culture movements can be addressed. However, these students’ aesthetic resistance nonetheless functions as a local reclamation of identification, autonomy, and community within the larger rhetorical space of a public state university. Their history provides regional texture to larger, international, and more popular disability arts movements, like the Disability Pride Association in the United States and National Disability Arts Collection and Archive (NDACA) in England. Therefore, to flesh this smaller movement out at much as possible, more time is devoted to the activity on this campus specifically.

Student Aesthetic Resistance

Grassroots Students Groups

The earliest record of disability-centered student newsletters at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG) appeared in 1982. There was a group of students on campus called the Association of Handicapped Student Awareness, or AH-SA. In their advertisements on campus, they make sure to note that “Membership is open to any UNC-G student” (OHSA Brochure, 1982, emphasis original). This group was open and willing to align itself with non-disabled students and cultivate intersectional allyships with the student body. Only a few years after Section 504 became law, these students were already working to dissolve institutional codes of exclusion and separation, or “logics of normativity,” as Dolmage (2017) would call them. “Logics of normativity” refer to the assumptions put in place by society which foster disablism, the devaluing of disabled bodies, and promote ableism, the disproportionately positive regard for able bodies; ultimately, the notion behind “logics of normativity” is that disability is “less-than-human” and able-ness is the “default” (Dolmage, 2014, p. 21-22). By inviting students of all abilities into this student disability group, these students are arguing that disability is everyone’s issue, dismantling the myth that it is “isolating and individuated,” one of Dolmage’s (2014) “Disability Myths” that influence the rhetorical performances and exchanges between abled and disabled bodies (p. 35). This group, then, demonstrates an embodied rhetoric of consubstantiality, of identifying with the issues of the other even if the issues do not affect one personally.

This group also participated in a “Special Arts Festival” every year, where students with disabilities could produce art of any kind and display it to their peers on campus. Therefore, beyond just subverting disability myths, these students are asserting themselves as subjects of aesthetic production. Siebers (2010) writes that “[d]isability aesthetics prizes physical and mental difference as a significant value in itself...it drives forward the appreciation of disability found throughout modern art by raising an objection to aesthetic standards and tastes that exclude people with disabilities” (p. 19). The archives do not detail the specific artwork on display at these festivals, but this practice continued throughout the early eighties. Therefore, in the earliest record UNCG has of student-centered disability groups, one can find evidence of aesthetic resistance and self-expression. These students also participated in the wide and public circulation of their disability experiences by encouraging student submission to the magazines Kaleidoscope and The Disability Rag, which promote works of art, literature, and political commentary by disabled individuals with themes that focus on disability’s intersectional role in American culture.

Students also turned to overtly political modes of expression and intertwined them with aesthetic rhetoric. In the 1989 DSS Newsletter, a student wrote a creative op-ed piece about the importance of individuals with disabilities having a political voice. She expresses her concerns over an apparent apathy in the disability community concerning this issue, and argues this attitude is detrimental because society already sees them as weak and powerless. She urges the community to come together as one and fight for their rights and for fair representation in government. The author then turns to the larger, able-bodied population and warns them of what may happen should people with disabilities continue to be excluded from mainstream politics by writing that this group of people with disabilities “may very well cause the mighty to tremble if their agenda continues to be ignored!” (DSS Newsletter, 1989). The author visually represents this political body of disabled individuals by inserting an image of Frankenstein’s monster in the middle of her op-ed piece (See Figure 2 below). She symbolizes, through a well-known literary creation, both the idea that this political body is made up of diverse parts, as well as the grotesque, othered, marginal, monstrous identity people with disabilities hold in mainstream consciousness. She repurposes this iconography of monstrosity and reclaims society’s creaturing of disabled bodies by envisioning them as a powerful force fighting for visibility and self-actualization in politics, a force to be reckoned with, not excluded, which further rejects Dolmage’s (2014) “kill-or-cure” disability myth, since Frankenstein also actively grappled with this narrative. This creative piece rhetorically overlaps Dolmage (2014, 2017) and Siebers (2010) effectively. The otherwise disqualifying aesthetic representation of disabled bodies as monstrous has now taken on a new rhetorical meaning, which Siebers (2010) argues is a pivotal aspect of disability aesthetics. Also, it performs this work in the space of a college newsletter, thus resisting the institutional and aesthetic codes of exclusion Dolmage (2017) theorizes in Academic Ableism.

Figure 2. An Image of the Op-Ed with the Creature’s Image from Frankenstein

Another UNCG student also turned to aesthetic performance in order to create a space of visibility and legitimacy. The Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Student Association, in conjunction with Disability Student Services, hosted a performance in 1991 entitled “Making Decisions for Life” by David Dean, a senior Anthropology student who relates the experiences and difficult decisions he has faced living with HIV while being a college student (DSS Newsletter 1991). This performance consisted of Dean undertaking the role of storyteller and relaying his experiences to the audience. He stands on a stage and invites the audience into a space of community and conversation, repeatedly opening the floor to questions and commentary. The flyer for this event reveals that his performance took place in the Elliot University Center, a hub of campus that is central to student life. Thus, by occupying this space, Dean argues for his place among his peers, despite his heavily stigmatized disability. By openly marking his body as disabled, and forming a narrative of disability around himself, Dean performs a material rhetoric. Siebers (2010) writes that understanding the materiality of words is central to understanding disability aesthetics because it all begins in the body (p. 123). Dean uses words to tell his story, but because he offers himself up as a visual embodiment of the narrative, his words are made flesh, and “when words gain materiality and appear in the world as visible things…[they] acquire an additional power as a result” (Siebers, 2010, p. 123, 124). By subjecting himself to scrutiny and inquiry, Dean directs his audience wholly towards his body, allowing them to form a critical connection between words, materiality, visibility and disability. This move cultivates a space for the possibility of reimagining and rearticulating the stigma surrounding a body that has been disabled by HIV. Also, by making himself a spectacle, Dean resists the ableist aesthetics that would mark his body as a failure, and instead embraces a form of disability aesthetics that would (re)imagine his body as an aesthetic site of knowledge-production and a radical, critical conception of the body (Dolmage, 2017, p. 173; Siebers, 2010, p. 139). Thus, one can see from these historical moments how disability aesthetics are also sites of intersectional rhetorical performances of queer resistance against institutional aesthetic norms.

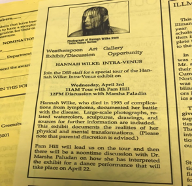

Hannah Wilke

An additional art piece these student groups hosted on campus was Hannah Wilke’s (1993) photography, sculpture, video, and watercolor series Intra-Venus. Much like Terry Galloway, Wilke’s art is blunt and shocking in its portrayal of disability, and it provides yet another layer of analysis within this theoretical framework of disability aesthetics and embodied rhetoric within the Institution. According to the 1994 student newsletter, “[t]his exhibit documents the realities of her physical and mental transformations,” from being initially diagnosed with lymphoma to being completely ravaged by it. The series showed the corporeal and mental effects of her disability. For example, she created a series of photographs showing her smiling with a full head of hair, then crying with a balding head, and finally lying exhausted in a bed or slumping in a portable toilet seat with a completely bald head. She also created a photo series that focused on her mouth, which went from a happy smile, to a sore, puss-filled scream. In most of these installations, Wilke looks directly into the camera and at the audience, a direct invocation and challenge to stare back at her.

Also, Wilke had passed by the time the exhibit came to UNCG, so this archival moment is also a haunting demonstration of the morbidity faced by individuals with disabilities, as well as a reminder of the human body’s mortality, which fuels the anxiety, disgust, and aversion disabled bodies evoke in society. Siebers (2010) tackles this idea of aversion by asserting that there is power in “pushing the representation of disability beyond the limits of representation itself” (p. 87). In other words, he argues that works of art which utilize familiar mediums (painting, photography, etc.) to depict disability detach aesthetic ideals from their “beautification program in order to present a vision of disability made stranger, not prettier” (p. 87). With this notion, Siebers (2010) demarcates the value of creating art which is difficult for audiences to consume, and which elicits visceral reactions from them because of the way it portrays disability. Disability in art should not only serve to make the art interesting or beautiful in a new and exciting way; sometimes it is unpleasant and painful, and the precise point of the artwork is to capture this unadulterated reality. This rearticulating of aesthetic production by the artist, and aesthetic appreciation by the audience, creates a new mode of knowledge production in which disability can exist in an unapologetic yet nonetheless aesthetically valid space. This notion further implicates Sieber’s theory that disability in art is vital because it “return[s] aesthetics forcefully to its originary subject matter: the body and its affective sphere” (p. 2). In this historical moment, the audience at UNCG is experiencing the pain harbored by a deceased woman’s body. In a way, Wilke’s engagement with the embodied rhetoric of disability aesthetics has immortalized her.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Wilke’s art is that she created images and videos of her body in various sexual performances, with intravenous needles sticking out of her breasts, and her inflamed genitals on display. In this moment, the series title Intra-Venus, itself a play on words, elicits critical rhetorical implications. Siebers (2010) writes that “visibility and the disabled body are closely linked,” and that photography especially forces audiences to participate in a practice of bodily discrimination, where they decide explicitly whether a body pleases them or not (p. 127). Wilke claims the title Venus, and indeed creates several photographs where she poses like the figure in Sandro Botticelli’s classical painting The Birth of Venus. However, not only does she embody the exact opposite of what traditional aestheticism would deem a beautiful female form, she also arranges these photographs alongside images of herself in less classical and more pornographic positions. She critiques “the assumptions of idealist aesthetics,” while simultaneously juxtaposing classical notions of beauty with erotica (Siebers, 2010, p. 2). Wilke’s art, therefore, engages in an aesthetic contemplation of the ways society has historically depicted and consumed images of the female body as well as how disability displayed on said female body complicates these systems of production, consumption, and value. Thus, by hosting Wilke’s work at UNCG’s prominent and public Weatherspoon Art Museum, as well as hosting forums to discuss the work, these students argue for the legitimacy of disability aesthetics, experiences, and presence in both mainstream artistic spaces and mainstream spaces on college campuses.

To extend this point further, Dolmage (2017) writes, “[t]he normative demand in academia is that disability must disappear,” but now that institutions accept disability as a reality, true and effective “[i]nclusion should mean the presence of significant difference—difference that rhetorically reconstructs” (p. 84). Dolmage (2017) asserts that students with disabilities must have a legitimate space to exist in the university, instead of being forced into institutionally-mandated retrofits which try to cover up disabled bodies or make them seem as able-bodied as possible. Therefore, by connecting Siebers with Dolmage, we can see the rhetorical value of these students hosting Wilke’s Intra-Venus on UNCG’s campus. The work took up space in the campus’s most historical and iconic art museum, arguably UNCG’s aesthetic center. It is a poignant argument for the validity of disability as both a critical knowledge-producing concept, and as a vital facet of the human experience within higher education.

Figure 5. A Headshot Photograph of Wilke Staring at the Camera from the Intra-Venus Series in which She Documents Her Hair Loss (Tierney)[3]

Figure 6. An Advertisement for Intra-Venus in the DSS Newsletter Featuring the Above Image of Wilke’s Headshot

Implications and Conclusion

Historical Links to Present Aesthetic Resistance

Paying critical attention to these historical accounts also provides a lens for examining present aesthetic protests on university campuses. For example, consider how universities typically depict important cultural figures on their campuses, like founders or historical “heroes.” They are usually statues of upright, white men in similar stoic poses. These statues are cultural sites, and the codes they embody a rhetoric of their own. Their bodies are all depicted the same way in a tidy, uniform fashion, just as institutions of higher learning align with tidy, uniform standards of academic success. A recent political moment involving one such statue, “Silent Sam,” that resides on the campus of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, further implicates the rhetorical significance of student aesthetic resistance on college campuses. On August 20th, 2018, students on UNC Chapel Hill’s campus tore down Silent Sam, who had been erected at a busy and symbolic nexus of the campus to honor confederate alumni who fought and died in the civil war more than a century ago (Deconto and Blinder, 2018).

The catalyst for this student-led razing was black UNC student Maya Little’s vandalizing of the statue earlier that year in which she splattered red paint mixed with her own blood on it, symbolically and literally performing the African and African American blood spilled at the hands of both confederate soldiers during the Civil War as well as white supremacists from Civil War times up to the present (The Tab, 2018). According to Siebers (2010), this act of damaging the representative body of the statue means it has taken on a different rhetorical meaning. Siebers (2010) argues that once a formerly whole piece of art is damaged, once the formerly able body of a statue is bloodied and broken up, for instance, “[b]eholders are free to fantasize about what [the] damaged [image] mean[s]”—for example, one more nail in the coffin of southern white supremacy (p. 83). The reality of the statue’s material content has changed, and with it, the rhetoric of the statue’s embodied form, “pushing the representation of disability beyond the limits of representation itself;” for instance, the statue transforming from a sight of honor to dishonor (Siebers, 2010, p. 87). Student aesthetic resistance has exposed the rhetorical codes and practices of institutional exclusion, and disability is an essential aspect of this defiance. This moment demonstrates Dolmage’s (2017) claim that aesthetics on college campuses demarcate sites of power and privilege as well as Sieber’s (2010) assertion that disability is a critical locus for challenging normative perceptions in aesthetic representation.

Figure 1. Silent Sam Statue with Student-Made Banner Wrapped Around it Which Reads “We Will Not be Intimidated.” Photo credit: Martin Kraft, 2018.[4]

Where the Archive Ends and Begins

Ultimately, what this article has sought to provide is an effective way to re-conceptualize disability history in higher education, carving out space in the official institutional narrative by necessarily and meaningfully cripping the archive and amplifying the presence of embodied disability rhetoric within histories of higher education—in this case, through aestheticism. This scope and focus emphasize the intricate aesthetic experiences and responses students with disabilities have undergone and continue to undergo on our campuses and in our classrooms in order to speak back to institutional mandates that they either assimilate or disappear. The regional snapshot I have provided reveals a rich potential for (re)investigating marginalized and silenced voices in our universities’ pasts and presents. Dolmage (2017) argues that “we [as scholars] must wonder whether what we have to offer is truly worthwhile if it translates into politics of exclusion...and reductive definitions of human worth” (p. 65). Therefore, even though disability in higher education is a complex and challenging issue, it is also an opportunity for rigorous investigation into the aesthetic codes, structures, and ideologies that perpetuate marginalization as well as strengthen resistance to it, especially in moments of modern-day regenerative activism as seen through Maya Little and the UNC students. History can show us how past actions inform our present adherence to practices of exclusion and ableism, and it can also reveal how effective and essential these rhetorical moments of disruption are.

Endnotes

1. Further information regarding specific statistics of students with disabilities attending institutions of higher learning can be found at the National Center for Education Statistics website: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=642. For more information regarding political protests in disability history, please consult: Scotch & Barnartt, 2001. 3. Reproduction of this image is allowed under the free license CC BY-SA 3.0. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode

4. Reproduction of this image is allowed under the free license CC BY-SA 3.0. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode

References

- Brophy, S., & Hladki, J. (2014). Cripping the museum: Disability, pedagogy, and video art. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 8(3), 315-333.

- Deconto, J. J., & Blinder, A. (2018, August 23). “Silent Sam” confederate statue is toppled at University of North Carolina.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/21/us/unc-silent-sam-monument-toppled.html

- Dolmage, J. (2017) Academic ableism: Disability in higher education. Michigan University Press.

- Dolmage, J. (2014). Disability rhetoric. Michigan University Press.

- DSS Fall 1989 Newsletter. UA 42.13, Box 1, Folder: Disabled Student Services. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro University Archives, Jackson University Libraries, Greensboro, NC. 23 March 2018.

- DSS Newsletter Fall 1991. UA 42.13, Box 1, Folder: Disabled Student Services. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro University Archives, Jackson University Libraries, Greensboro, NC. 23 March 2018.

- DSS Newsletter Spring 1993. UA 42.13, Box 1, Folder: Disabled Student Services. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro University Archives, Jackson University Libraries, Greensboro, NC. 23 March 2018.

- DSS Spring 1994 Newsletter. UA 42.13, Box 1, Folder: Disabled Student Services. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro University Archives, Jackson University Libraries, Greensboro, NC. 23 March 2018.

- GlobalVillageVidiot (2013, April 6). Out all night and lost my shoes [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYQVbETY9W8

- Kaier, A. (2011). The Examining Table. In J. Barlett, S. Black, & M. Northern (Eds.) Beauty is a Verb. (pp. 236-237). Cinco Puntos Press.

- Kraft, M. J. (2017). Protests against the statue of Silent Sam on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MJK49379_Silent_Sam.jpg

- Kuppers, P. (2011). Crip music. In J. Bartlett, S. Black, & M. Northern (Eds.) Beauty is a verb (p. 116). Cinco Puntos Press.

- Making Decisions for Life. Box N/A, Folder: Disability Services, Office of (formerly Disabled Student Services, Office of). The University of North Carolina at Greensboro University Archives, Jackson University Libraries, Greensboro, NC. 23 March 2018.

- Mayer, B. (2011). EYJAFJALLAJOKULL. In J. Bartlett, S. Black, & M. Northern (Eds.), Beauty is a verb (p. 363). Cinco Puntos Press.

- Office of Handicapped Student Awareness Brochure 1982. UA 42.13, Box 1, Folder: Disabled Student Services. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro University Archives, Jackson University Libraries, Greensboro, NC. 23 March 2018.

- Scotch, R., & Barnartt, S. (2001). Disability protests: Contentious politics, 1970 - 1999. District of Columbia: Gallaudet UP.

- Sexton, D. UNC’s Silent Sam statue torn down by protesters. (2018, August 21). The Tab, North Carolina State University. https://thetab.com/us/ncstate/2018/08/21/uncs-silent-sam-statue-torn-down-by-protesters-2376.

- Siebers, T. (2010) Disability aesthetics. Ann Arbor: Michigan University Press.

- Spaghet-Ti (2018). Silent Sam statue in UNC-Chapel Hill [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Silent_Sam_Statue_in_UNC-Chapel_Hill.jpg_01.jpg.

- Tierney, H. (1996). Hannah Wilke: The intra-Venus photographs. Performing Arts Journal, 18(1), 44-49.

- Weise, J. (2011). The body in pain. In J. Bartlett, S. Black, & M. Northern (Eds.), Beauty is a verb (pp. 148-149). Cinco Puntos Press.