The Myth of Independence as Better: Transforming Curriculum Through Disability Studies and Decoloniality

Maria Karmiris

Ryerson University

mkarmiris [at] ryerson [dot] ca

Abstract

By situating this article within disability studies, decolonial studies and postcolonial studies, my purpose is to explore orientations towards independence within public school practices and show how this serves to reinforce hierarchies of exclusion. As feminist, queer and postcolonial scholar Ahmed (2006, p. 3) contends, “Orientations shape not only how we inhabit, but how we apprehend this world of shared inhabitance as well as ‘who’ or ‘what’ we direct our energy toward” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 3). I wonder how the policies and practices that I am oriented towards as a public school teacher limit the possibilities of encountering teaching and learning as a mode of reckoning and apprehending “this world of shared inhabitance?” I also wonder how remaining oriented towards independence as the goal of learning simultaneously sustains an adherence to colonial western logics under the current neoliberal ethos. Through Ahmed’s provocation I explore how the gaze of both teachers and students in public schools remains oriented towards independent learning in a manner that sustains conditions of exclusion, marginalization and oppression.

Keywords:Inclusive Education, Independence, Interdependence, Disability Studies, Decolonial Studies, Postcolonial Studies

Introduction

By situating this article within disability studies, decolonial studies and postcolonial studies, my purpose is to explore orientations towards independence within public school practices and show how this serves to reinforce hierarchies of exclusion. As feminist, queer and postcolonial scholar Ahmed (2006, p. 3) contends, “Orientations shape not only how we inhabit, but how we apprehend this world of shared inhabitance as well as ‘who’ or ‘what’ we direct our energy toward” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 3). I wonder how the policies and practices that I am oriented towards as a public school teacher limit the possibilities of encountering teaching and learning as a mode of reckoning and apprehending “this world of shared inhabitance?” I also wonder how remaining oriented towards independence as the goal of learning simultaneously sustains an adherence to colonial western logics under the current neoliberal ethos. Through Ahmed’s provocation I explore how the gaze of both teachers and students in public schools remains oriented towards independent learning in a manner that sustains conditions of exclusion, marginalization and oppression.

This article is composed of two parts. In part one, I explore the ways in which Ontario Ministry of Education assessment and evaluation documents such as Growing Success (2010) valorize independence in a manner that continues to generate the conditions for precarious inclusion. There are three elements to my argument in part one. First, I describe the relationship of independence to sustaining the neoliberal ethos of “competitive individualism” (Moore & Slee, 2012, p. 228). Similarly, I focus on how a belief in achieving independence is related to sustaining a binary between independence and dependence that often represents disabled children and youth as always and already failing to measure up. Finally, this analysis of the limits of valorizing independence as the goal of learning addresses the relationship of independence to western colonial logics and the subsequent sustaining of power imbalances that disproportionally impact children and youth based on the persistent presence and experience of racism, classism, ableism, homophobia and transphobia within schooling practices.

After demonstrating the limits of independence as the ultimate goal of learning, part two of this article engages the work of postcolonial, decolonial, disability, queer and feminist scholars to consider the possibilities of a resistance and refusal of the myth of independence. I am guided by Ahmed (2006), Million (2011) and Yergeau (2018) in disrupting the myth of independence while inviting the possibilities of working within disorienting intersubjective encounters. In part two of this article, I use disorienting intersubjective encounters as a way to explore three strategies for reckoning with the harm and injustices experienced in public schools. First, I consider the importance of confronting racist, classist and ableist legacies that are sustained through the myth of independence and its subsequent unbalanced relations of power. Second, I explore disorienting intersubjective encounters as a way to question and resist the binary of independence and dependence. Finally, through a foregrounding of our interdependencies, I question the neoliberal logics of competitive individualism and the social injustices they sustain. Overall, my aim in this article is to engage in a sincere questioning of the implications of remaining oriented towards independence as the goal of learning in public education. I do so in order to demonstrate the role of such orientations in sustaining the conditions of injustice and exclusion in schooling practices.

Growing Success and Measuring Independence

Striving towards independence as an individual remains a taken for granted goal in public education from grades 1-12. This goal is not only ubiquitous and deeply embedded in assessment and evaluation practices, it also continues to be depicted as the only pathway forward in learning. For example, the front cover (Figure 1) of one of Ontario’s assessment and evaluation policy documents Growing Success (2010) shows an image of an outstretched hand, directly above the palm of which a seed is juxtaposed against a ruling measure. Immediately above and to the right of the image of this seed is an image of a single seedling which is also juxtaposed against a ruling measure. Approaching the top right corner of the cover is an image of a tree standing alone alongside yet another ruling measure. The image of the seed, seedling and tree that follow each other in a vertically inclining line on this cover reveal a great deal about the purpose and intention of the policy document that currently guides assessment and evaluation practices in Ontario. Rather than situating the seed, seedling and tree in the midst of a complex interconnected ecological web, the seed, seedling and tree are deployed to represent a singular pathway of development. Progress is represented on the front cover of Growing Success (2010) as a sequential process of linear independent growth that intends to distance itself from needing any helping hand. Before even reading any of the one hundred sixty-eight pages of policy guidelines about assessment and evaluation, the cover depicts teaching and learning as an act of producing independence that seemingly remains untouched and increasingly distanced from the hand of another.

Figure 1 Front Cover of Growing Success: Assessment, Evaluation and Reporting in Ontario Schools (2010)

To consider the implications of this taken for granted orientation toward learning as a path towards independence and its subsequent relationship to the neoliberal ethos of “competitive individualism” (Moore & Slee, 2012, p. 228), I first turn to the work of disability studies scholars Dolmage (2017) and Moore and Slee (2012). In Academic Ableism (2017), Dolmage critiques how post-secondary institutions continue to conditionally include and/or outright exclude students who identify as disabled. He foregrounds the metaphor of steep steps: “The steep steps metaphor describes how the university has been constructed as a place for the very able. The steep steps metaphor puts forward the idea that access to the university is a movement upwards—only the truly ‘fit’ survive this climb” (p. 44). Distinct from yet linked to the architectural and rhetorical presence of steep steps that shape the university setting (Dolmage, 2017), learning in elementary and secondary public school settings is also depicted as a steep climb. If the goal of learning as depicted on the front cover of Growing Success (2010) is to move up and away from needing a helping hand, what might it mean to be spatially and tangibly closer to an outstretched palm of a hand? In other words, we might consider the implicit association of depending on helping hands with lack and an inability to make it to the top of the steep climb. Thus, the steep incline depicted on the front cover of Growing Success (2010) can also be read as a representation of a possibility for some rather than a pathway for all.

Despite the commonplace rhetoric of inclusion in our contemporary moment, public schools remain places and spaces committed to the valorization of independence in a manner that simultaneously reinforces ableism. According to disability studies in education scholars Moore and Slee (2012, p. 228), “Education policy follows the neo-liberal moral compass. Competitive individualism is both ethos and practice…The imposition of a national curriculum that embraces particular cultural class and gender values excludes many of the students destined to experience it.” What Moore and Slee (2012) point to here and what has been echoed by the work of numerous disability scholars like Dolmage (2017), is that there remains a disjuncture between inclusionary rhetoric and policies and the subsequent adherence to assessment and evaluation practices that assume progress and success as the result of individual effort and reward. While Dolmage’s (2017) work focuses on ableism and steep steps within post-secondary institutions and the work of Moore and Slee (2012) offers a critique of inclusive practices in public education, the works share in common an attention to how the valorization of an independent self remains the goal education is oriented towards.

In my practice as an elementary public school teacher in Toronto since 2002, the work of Moore and Slee (2012) and Dolmage (2017) has helped me attend to the broader implications of policies and practices expressed in official documents like Growing Success (2010). While the first part of this article uses an example from Ontario, the implications of my analysis are linked to a broader critique of how the myth of independence is situated within the kinds of colonial western logics that sustain the conditions for injustice. Achieving independence remains a central element of evaluation criteria in a manner that foregrounds a western-centric conception of selfhood. It also sustains a “competitive individualism” that the neoliberal ethos depends on in order to sustain its hegemonic role (Moore & Slee, 2012). I turn here to another example within Growing Success:

This quote shows how measuring and monitoring student progress towards independence is conceptualized as inseparable from what it means to teach and learn in school. While differences of race, gender, class, disabilities, and sexual orientations are never explicitly mentioned, data from school boards like the Toronto District School Board consistently demonstrate how mechanisms to measure and monitor progress impact racialized and low-income communities in a disproportional manner (Brown & Parekh, 2016). Similarly, Black students and/or students from low-income areas are disproportionally identified as disabled (Brown & Parekh, 2016).

The rhetoric of independence that remains commonplace in assessment and evaluation documents like Growing Success (2010) continues to generate and sustain conditions of exclusion within educational spaces. This occurs through the unexamined consequences of sustaining the hegemony of a western-centric conception of selfhood, one that is embedded in a form of colonial western logics and persists in valorizing the value of ascending to the top. This is one of the key foci of Dolmage’s work (2017, p. 45), which also contends that along with disability, steep steps “unite many other discourses of normativity: whiteness, heteronormativity, empire, colonialism and masculinity.” This conclusion that the ascent to the top of steep steps is intended to exclude is also supported by the analysis of Moore and Slee (2012) who point to the persistent gap between stated inclusionary policies and persistent experiences of exclusion of children and youth identified as disabled. It is the very few who survive the linear assent to the top.

According to Ahmed (2006), orientations shape human perceptions: “We say we are oriented toward something… the thing we are oriented toward is what we face, or what is available to us within our field of vision” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 115). In reflecting on this quote from Ahmed, I wonder what happens to the countless students who never reach the top of the steep climb. Despite claims that “every student is unique and each must have opportunities to achieve success” (Growing Success, 2010, p. 1), I wonder how educational orientations towards independence are complicit in sustaining the conditions of exclusion and/or marginalization in schools. In other words, how do orientations towards independence as the measure of learning sustain the hegemony of colonial western logics and the white, able-bodied, heteronormative male as the pinnacle of growing success? Throughout Growing Success (2010), independence is depicted as an object of ongoing monitoring and measurement. There are rulers beside each of the images of the seed, seedling and tree that remind readers of the role of measurement throughout the learning process. Sustaining an adherence to the ascending line of growth requires a commitment to measurement; a commitment to counting how close or far away any given student remains along this line of independence.

Moore and Slee (2012), along with critical pedagogy scholar Au (2016), provocatively suggest that current assessment and evaluation practices orient teachers and students toward an individual failure to measure up in order to avoid addressing structural inequities in education. For example, by critiquing the wide-spread use of standardized tests in public education, Au (2016, p. 46) troubles “the ideology of meritocracy [which] asserts that regardless of social position, economic class, gender, race, or culture… everyone has a chance of becoming ‘successful’ based purely on individual merit and hard work”. Au demonstrates how standardized tests are rooted in racist logics that disproportionally identify Black children, youth and the communities they inhabit as “failures” (pp. 42-3). Relatedly, Moore and Slee (2012, p. 227) describe how children with disabilities “represent a threat to the ranking and rating of schools.” In an effort to avoid poor school ratings and rankings, “schools have looked at ways of jettisoning difficult and hard-to-teach children” (ibid., p. 227). This process of labelling Black, low-income and/or disabled children as always and already failing to ‘measure up’ continues to occur alongside stated educational policy claims of inclusion (Moore & Slee, 2012), multiculturalism and a commitment to civil rights (Au, 2016). Thus, under the guise of achievement and success, sustaining the myth of independence also sustains unjust hierarchies of conditional inclusion if not out-right exclusion.

Disability studies scholars have offered insights and analyses into the ways that current education policies and practices that valorize independence simultaneously pursue practices of conditional inclusion that are also deeply embedded in practices of assessment and evaluation (Annamma et al., 2013; Brown & Parekh, 2013; Collins et al., 2016; Erevelles, 2013; Graham & Slee, 2008; Moore & Slee, 2012). For example, Annamma et al. (2013), as well as Collins et al. (2016) point toward the disproportionate number of students labelled with learning disabilities that are either Black and/or from lower socio-economic income groups (Annamma et al., 2013; Collins et al., 2016). Similarly, in my local context of the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), Brown and Parekh (2013) offer numerous statistical representations of the disproportionate impacts of special education labelling practices based on gender, race and class. The findings of Brown and Parekh (2013) substantiate concerns raised in the work of Annamma et al. (2013) and Collins et al. (2016) which show the role of assessment and evaluation practices in continuing to limit access to social belonging and educational opportunities based on race, gender, class and disability. What becomes evident in these brief examples is that the maintenance of the inclining line of progress towards independence, depends upon a gradient of success that in the words of Moore and Slee (2012, p. 228) “create more barriers to student participation in schooling.” Not everyone is meant to follow the line all the way to the top. Thus, a valorization of the independent self through assessment and evaluation practices ultimately implicate elementary policy documents like Growing Success (2010) in perpetuating and sustaining social injustices and unbalanced relations of power.

To be counted among the independent along the inclining line encompasses both privilege and exclusivity in ways that should prompt teachers, students, parents and administrators to consider how we come to be implicated in sustaining the belief that cultivating independence is a primary goal of teaching and learning. For example, Gaztambide-Fernández and Parekh (2017, p. 4) contend that the commodification of educational programs as products acts as “a key mechanism through which structural inequalities are reproduced.” In their analysis of admission and attendance for Specialty Arts Programs (SAP’s) at the secondary level in the TDSB, Gaztambide-Fernández and Parekh (2017, p. 19), demonstrate that the rhetoric of individual choice conceals “an educational pathway that is shaped by the structural advantages inherent to whiteness and to having access to economic, cultural and social capital.” One example of a key finding in their statistical analysis includes reporting that “over one-half (56.7%) of the students who entered Gr. 9 in SAP’s in 2011 were likely to come from families representing the three highest income deciles in the TDSB” (Gaztambide-Fernández & Parekh, 2017, p. 7). Whiteness and economic privilege in their study are tethered to the rhetoric of ‘choice’ that comes to feed the belief in exceptional abilities and the value of “neoliberal free-market individualism” (Gaztambide-Fernández & Parekh, 2017, p. 4). Similarly, according to the findings of Gaztambide-Fernández and Parekh (2017), the rhetoric of exceptional talent works with choice to conceal the networks of support and opportunity within which affluent youth who attend SAP’s are embedded. What appears to be the exceptional talent and achievement of individuals thus comes to be revealed as a social network of privilege that applies the rhetoric of choice to sustain its socio-cultural advantage while preserving mechanisms of inequality.

Thus far, in the first part of this article, I have focused on the relationship between independence and the colonial western logics that have shaped the neoliberal ethos of the present moment. I have explored the ways assessment and evaluation documents like Growing Success (2010) contribute to sustaining the conditions of exclusion through their focus on a competitive individualism. This orientation towards independence sustains structural inequalities that disproportionately impacts children and youth based on racism, classism, ableism, homophobia and transphobia. Before moving on to the second part of this article, I also want to take some time to explore the relationship between how orientations towards independence sustain a binary between independence and dependence. This binary relationship often depicts dependence as a negative attribute of the human condition. To return to the depiction of the seed, seedling and tree on the cover of Growing Success (2010), progress from one stage to the next is represented as a journey that occurs in isolation from other human and non-human life forms. In reality, seeds/ babies, children/ youth, seedlings, adults and trees are embedded “in a world of shared inhabitance” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 3). If we are indeed embedded “in a world of shared inhabitance”, as Ahmed conveys, how do current orientations towards independence not only limit the possibilities of such an enactment but, contribute to orientations towards dependence that sustain the ableist notions of disability as lack and deficiency? How might we work towards intersubjective encounters with each other that embrace the ways in which we are dependent on one another at different levels of frequency and intensity over our lifetimes? How does remaining oriented towards the image depicted on the cover of Growing Success (2010) not only sustain structural inequalities, but sustain a binary relationship to the notion of dependence that continues to negatively impact our teaching and learning relationships as well as our social relations with each other?

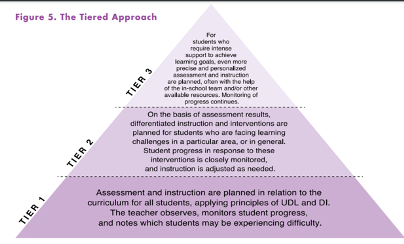

In an Ontario Ministry of Education policy document that works in conjunction with Growing Success (2010), Learning for All (2013) outlines a standard of practice known as tiered intervention (see Figure 2). In addition to foregrounding the significance of ongoing assessment and evaluation of individual students, the very top of the pyramid, labelled as Tier 3, indicates that attaining the highest level of support/ dependence (i.e. human and/or material resources) is a category reserved for the fewest students (Learning for All, 2013). Within the context of children who identify with a disability, every layer of support and any requests for additional support require concrete evidence to substantiate claims for the allocation of funds (Learning for All, 2013). To require and seek the benefits of a social network of support in the realm of special education is to be scrutinized and monitored through a variety of interlocking processes that include but are not limited to the development and implementation of Individual Education Plans (IEP’s). IEP’s describe varying degrees of support and act as a mechanism of revealing rather than concealing the ways different humans depend on others and the world around them to both survive and thrive. Thus, while parents with white privilege and socio-economic affluence conceal networks of support for their children through the rhetoric of exceptional talent and individual ‘choice’ (Gaztambide-Fernández & Parekh, 2017), disabled children are excessively assessed and reassessed by the special education process that places some exceptional students in the third tier of support. When the highest tiers of both ‘independence’ and ‘dependence’ are juxtaposed against one another, it paradoxically reveals the ways social networks of privilege and inequality mutual constitute one another. In other words, the myth of independence survives through the simultaneous process of overly scrutinizing the rationale for gradations of dependence.

Through following the inclining line of progress that is supposed to lead to independence, what comes to be both concealed and revealed is the import of dependence. Dependence on material and human resources (e.g. private lessons, extra practice and training, access to expert coaches and extra-curricular opportunities) bolster some children and youth with labels of giftedness, talent and well ‘earned success’ (Gaztambide-Fernández & Parekh, 2017). In other instances, dependence continues to have children labeled with disabilities at risk of being read as ‘failures’ for requiring support and assistance. This exemplifies how education works to offer a privileged experience to some students, while offering children with disabilities opportunities for conditional inclusion or outright exclusion (Graham & Slee, 2008).

Children with disabilities and their parents repeatedly report frustration with a special education system that conveys through its rhetoric of accountability that human and material resources for disabled children are scarce and require justification for their allocation. Besides my encounters as a teacher with parents and students, research conducted by numerous disability scholars substantiate this claim (Adjei, 2016; Connor & Berman, 2016; Connor & Cavendish, 2017; Hodge, 2016; Lalvani & Hale, 2015). Often parents reluctantly accept the processes of labelling merely to access human and material resources to support their children (Hodge, 2016). The work of Lalvani and Hale (2015) point to the ways parent advocacy has both prompted schools to adjust policies and allocate resources for students with disabilities while also showing its limits as a method of change due to the disproportionate advantage advocacy offers middle class parents with adequate social capital. Gaining access to resource support for disabled children through processes and procedures layered with accountability measures generates this paradoxical relationship to support as both a hard-won prize worth fighting for and a stigma that irreparably impacts the trajectory of disabled children whose varying modes of dependencies places them at greater risk of social exclusion (Adjei, 2016; Connor & Berman, 2016; Connor & Cavendish, 2017; Hodge, 2016; Lalvani & Hale, 2015). Thus, in the pushing and pulling for support, disabled children and their families, inhabit a mode of uncertainty that invariably questions their own humanity and their sense of belonging within educational contexts.

Thus far I have explored some of the limitations of independence as a goal students and teachers should be oriented toward. Through a focus on the exclusions experienced by children and youth because of ableism, racism and classism, I have aimed to demonstrate how the myth of independence also sustains unbalanced relations of power, structural inequalities as well as a binary relationship to dependence. The myth of independence is tethered to the kinds of colonial western logics that persistently pose challenges to creating the kinds of inclusive learning communities that would thrive within a myriad of embodied differences. If making it to the top of the steep climb of Growing Success (2010), is only intended for the few, what happens when the demands of this impossible climb are refused? In the second part of this article, I return to Ahmed’s provocation regarding orientations in this world of “shared inhabitance” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 3) to further consider the disorienting impacts of refusing current curricular orientations toward independence. What happens when in questioning and resisting orientations towards independence we also begin to consider the possibilities of foregrounding our interdependencies while embodying the disorientations that this comes with? Here, I turn to the work of postcolonial and feminist scholar Ahmed (2006), Indigenous scholar Million (2011, 2013) and disability studies and queer studies scholar Yergeau (2018) in order to focus on three aims. One of my aims is to consider the role of disorienting intersubjective encounters in confronting unbalanced relations of power. Secondly, I consider how disorienting intersubjective encounters might offer ways to refuse and resist the binary logics of independence and dependence. Lastly, I consider how disorienting intersubjective encounters can be deployed in order to confront the harmful impacts of the neoliberal logics of competitive individualism. Ultimately, I want to explore the fruitful possibilities for teaching and learning when we move beyond orientations towards independence in order to generate the conditions for children and youth of diverse backgrounds, identities and embodiments to thrive.

Speculations on Teaching and Learning Through Disorienting Intersubjective Encounters Amidst Disability

What follows in this section is a consideration of the fruitful possibilities of conceptualizing teaching and learning as an enmeshed network of disorienting intersubjective encounters that seeks alliances across, through and amidst a myriad of intersecting embodied differences in order to re-imagine our human relations. I foreground disorienting intersubjective encounters here as a way to explore alternatives to sustaining orientations towards achieving independence as the goal of learning. I pay particular attention here to the important critical intervention from Ahmed (2006, p. 159), who states that “disorientation is unevenly distributed: some bodies more than others have their involvement in the world called into crisis.” As a teacher who also remains perpetually a student, I take this provocation from Ahmed as a strong reminder that finding ways to teach and learn differently with each other entails a commitment to confront the harms generated and sustained through the unbalanced relations of power embedded in colonial western logics. The uneven distribution of opportunity and access to learning sustained by current policies and practices evident in documents like Growing Success (2010) have to be confronted and acknowledged as disorienting. These disorientations with processes of conditional inclusion and outright exclusion lead to teaching and learning amidst an atmosphere of suspicion and mistrust of an education system intended to benefit some not all students. If only some are intended to make it up the steep steps of growing success, both disorientation and disenchantment with school policies and practices are mutually constitutive outcomes. How can a disabled child or youth and their parent or caregiver commit to engaging in the teaching and learning process within the context of multiple experiences with racism, ableism, classism, sexism, homophobia or transphobia? How might teaching and learning invite those who frequently remain excluded into the process of reimagining what teaching and learning could be?

The possible paths ahead are uncertain and the answers to questions above are unknown to me. However, I contend that part of the transformation of current teaching and learning practices—a transformation this current article forwards—entails encountering moments of disorientation within the hegemony of colonial western logics as opportunities to confront and refuse the logics of documents like Growing Success (2010). Million (2013, p. 17) succinctly summarizes the aims of the current neoliberal ethos that permeates social institutions like schools and policy documents like Growing Success (2010) as “imbued with a powerful belief in the goodness of the market, in a claim that individual pursuits of self-interest will promote the public good.” Million’s conception offers a distinctly different pathway forward within which our dependencies amidst one another and nonhuman life are integral to human relations. For Million (2011, 2013), human dependencies are inextricably enmeshed within human relations in a manner that disrupts the hegemony of the myth of independence.

Through foregrounding the importance of decoloniality, Million critiques the neoliberal ethos and its attendant orientations to fostering a competitive individualism by contending that Indigenous epistemologies and their refusal of liberal rights-based regimes, offer a distinctly different orientation to what it might mean to teach and learn with each other:

Indigenous women articulate a polity imagined in Indigenous terms, a polity where everyone—genders, sexualities, differently expressed life forms, the animals, the plants, the mountains—are already included as subjects of the polity. They are already empowered, not having to argue for any ‘right’ to recognition; they form that which is the polity, that which is respected and in relation. That kind of polity would do more than ‘reform’ any relations, it would bring us beyond ‘representation’. (2013, p. 132)

Significant in Million’s articulation of life as living in relation with and tethered to “differently expressed life forms” is the way it foregrounds a sense of mutuality amongst varying versions of the human amidst a living planet with all of its myriad human and non-human embodiments of life. It is a clear foregrounding of a conception of intersubjective encounters and what it might mean to engage in our human and non-human relations in distinctly different ways. In decentering the Western, liberal, humanist subject, Million (2013) enacts a refusal to have life and living be confined to an atomized version of the self that simultaneously sustains the conditions of exclusion and oppression. Life defined through relation in a broad constellation of material and immaterial forms, that comprise an interdependent web, also foregrounds a sense of humility amongst one another as living beings (Million, 2013). Within this hopeful possibility, teaching and learning might instead begin to treasure encounters with varying embodiments of life in human and nonhuman forms as indicative of opportunities to learn with and from differences. Similarly, we might begin to consider, more sincerely, the most vexing question facing human forms of life amidst other living beings: How might we work with one another to create systems, structures and institutions that assure that life in all its varying embodiments not only survives but thrives?

Therefore, in the midst of disorientations where “the body in losing support might then be lost, undone, thrown” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 157), it becomes all the more significant to create and sustain alliances across our differences in a manner that foregrounds the importance of intersubjective encounters. Finding ways to foreground the importance of intersubjective encounters within the current context of schooling, one that continues to stigmatize varying modes and intensities of dependency, subsequently entails engaging in what decolonial and indigenous scholar Dian Million (2011, p. 313) refers to as “intense dreaming”. Routed and rooted through unjust impositions of colonial western logics that have sought to and continue to seek to erase Indigenous knowledges, Million (2011, p. 313) contends that “dreaming often allows us to creatively sidestep all the neat little boxes that obscure larger relations and syntheses of imagination.” In following Million (2011) and turning toward the work of Ahmed (2006) and Yergeau (2018), the boxes I seek to sidestep are the ones full of assessment checklists, success criteria and evaluation policy guidelines like those represented in documents like Growing Success (2010). Million (2011) here points to the necessity of evoking the human imaginary in order to not only confront the oppression and marginalization of colonial western logics but to dramatically transform the conditions of our human relations with each other. Inhabiting an unjust educational structure, provides both an urgency and necessity to Million’s provocation towards intense dreaming across, through and in the midst our intersubjective encounters.

The possibilities of reimagining our teaching and learning relations through disorienting intersubjective encounters is not offered with the intent of sustaining the current binary of independence and dependence. Nor are the multiple possible trajectories of disorienting intersubjective encounters offered as the foregrounding of yet another binary between intersubjectivity and the conceptualization of the unitary western subject. Rather, placing intersubjective encounters in the foreground of teaching and learning relationships leaves you and I and us unavoidably facing and confronting the ongoing legacies of unjust relations of power that have been sustained through an adherence to colonial western logics. If as Ahmed contends (2006), unjust power relations have been and are encountered within distinctly different levels of intensity, foregrounding intersubjective encounters within our teaching and learning relationships also entails reaching out toward each other while remaining attendant to the risks of harm inflicted within the current structure as we aim to avoid the reproduction of social and educational inequality. Therefore, even as Million (2011, p. 313) provokes an intense dreaming that “allows us to creatively sidestep little boxes,” it is important to consider that the valorization of independence also depends upon the logic of side stepping and in many respects stepping over other humans in order to preserve the hegemony of able-bodied heteronormative male whiteness. Thus, within a decolonial project that follows Million’s (2011) provocation of intense dreaming and Ahmed’s (2006) representation of disorientation, foregrounding intersubjective encounters must remain wary of overstepping and/or overreaching in the ways colonial western logics continue to do.

Attending to the possibilities of disorienting intersubjective encounters between varying embodiments involves a sustained commitment to remaining aware, as teachers and scholars, of the ethical conundrums involved in troubling the everyday ways that the hegemony of colonial western logics continues to overreach and overstep. An example of overreaching and overstepping can be found in the current orientations of educational policy documents like Growing Success (2010). This document is riddled with examples that take for granted that orientations towards independence are the best and only path forward. For example, when addressing the need for alternative curriculum expectations on Individual Education Plan (IEP), Growing Success (2010, p. 73) states: “Alternative learning expectations should be measurable and should specify the knowledge and/or skills that the student should be able to demonstrate independently, given the provision of appropriate accommodations.” Within this statement, the inexorable march from disability to ability and the subsequent necessity of the teacher’s role in monitoring and measuring this movement towards what is described as progress, is taken for granted as the only path of learning. Critical disability scholar Yergeau (2018) troubles the ways schools continue to discount disabled children and youth by questioning regimes of compliance, measuring and monitoring that continued to be extolled as best practices. Yergeau’s (2018) specific critique of practices such as Applied Behavioural Analysis (ABA), not only question orientation towards independence in schooling, but also expose the trauma inflicted on autistic children and youth through teaching and learning practices that are steeped in ableism.

When Yergeau’s work (2018) encounters the work of Ahmed (2006) and Million (2013), the non-innocence of orientations towards independence are not only placed in the foreground, but also demonstrate the injustices within teaching and learning practices that continue to adhere to colonial western logics. In Yergeau’s (2018, p. 147) critique of school practices that remain oriented towards ableism, Yergeau provocatively asks: “How does one invite discourse when that discourse insists on your eradication?” Yergeau’s question is intended to shake educators out of their complacency in order to reconsider adherences to assessment policies and practices that assure disabled children and youth are always and already read as failures for not measuring up to able-bodied norms. While Yergeau foregrounds the intersections of autistic and queer embodiments in her critique of teaching and learning practices, Ahmed (2006) questions both the orientations of heteronormativity and whiteness within the following of straight lines. Through a distinctly different encounter with the disorienting impacts of colonial western logics, Million (2013) critiques the residential school system which devastated Indigenous communities in Canada throughout the twentieth century. According to Million (2013, p. 44), “While residential schools’ stated goals were to Christianize and civilize children and communities, in practice this meant preventing Indian communities and families from modeling their own domestic relations to their children.” These efforts to erase and eradicate Indigenous cultures was an abuse of power that also marked the bodies of countless children and youth through verbal, physical and sexual abuse (Million, 2013). Even as these encounters with the hegemony of colonial western logics demonstrate how dehumanizing such orientations remain, these distinctly different examples are in many ways incomparable as they are distinct manifestations of injustice that have created distinct experiences of harm. Impossibly disorienting, this orientation towards sustaining independent, able-bodied, heteronormative male whiteness as the measure of success continues to remain the taken for granted trajectory for teaching and learning.

Throughout this article, I have attempted to demonstrate how assessment and evaluation documents like Growing Success (2010) valorize independence in ways that sustain injustice by adhering to and sustaining colonial western logics. Despite being embedded within teaching and learning encounters that continue to demonstrate a hostility towards embodied differences, the work of Million (2013), Ahmed (2006) and Yergeau (2018) confront these injustices while also insisting on the possibility of distinctly different orientations within our human relations. Ahmed (2006, p. 158) states, “The point is not whether we experience disorientation… the point is what we do with such moments… —whether such moments can offer us hope of new directions, and whether new directions are reason enough to hope.” Ahmed’s (2006) distinct ambivalence in the possibility of reorienting our teaching and learning relationships is also present in Yergeau’s (2018, p. 173) question: “How might autism claim rhetoric as it dismantles it?” Yergeau’s (2018) question here is particularly provocative as it challenges the dehumanizing discourses common in educational settings that view autistics as incapable of rhetoric. Yet, Yergeau’s (2018, p. 179) project not only troubles the neoliberal ethos, it also insists that “to be autistic is to negotiate inventional movements, movements that straddle the rhetorical and non-rhetorical, that muddle and murk”. Disorienting intersubjective encounters are undeniably stuck in the murk of western colonial order. Yet, through, across, and in the midst of embodied differences, disorienting intersubjective encounters invite the possibilities of reimagining our teaching and learning encounters by confronting and refusing unjust relations of power.

Concluding Thoughts

The purpose of this article has been to question orientations towards independence as the goal of teaching and learning. The impact of valorizing independence as the goal of learning is the simultaneous maintenance of methods of conditional inclusion for students who find themselves at the intersections of disability, race, gender and/or class differences. Valorizing independence conceals the networks of dependence that both disabled and nondisabled youth are embedded within in a manner that continues to stigmatize dependencies in ways that disproportionally impact the lives of disabled students. This article has also suggested that foregrounding disorienting intersubjective encounters within teaching and learning relationships might offer fruitful possibilities in both confronting the unjust power imbalances that striving towards independence generates, while also offering opportunities to become reoriented differently in our teaching and learning relationships amidst disability. Million’s (2013, p. 76) work serves as a reminder here that “Stories form bridges that other peoples might cross to feel their way into another experience”. Disorienting intersubjective encounters that meet at the intersections of disability, race, gender and/or class may offer such bridges whereby you and I and us can meet in between “the muddle and the murk” (Yergeau, 2018, p. 179); whereby our teaching and learning encounters can refuse to sustain the hegemonic unjust power relations of neoliberal policies while also finding new ways to become human amidst our embodied differences.

References

- Adjei, P. B. (2016). The (em)bodiment of blackness in a visceral anti-black racism and ableism context. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(3), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1248821

- Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer phenomenology: Orientations, objects, others. Duke University Press.

- Annamma, S. A., Connor, D., & Ferri, B. (2013). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. Race Ethnicity and Education, 16(1), 1-31. DOI: 10.1080/13613324.2012.730511

- Au, W. (2016). Meritocracy 2.0: High-stakes, standardized testing as a racial project of neoliberal multiculturalism. Educational Policy, 30(1), 39-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904815614916

- Brown, R.S., Parekh, G., & Marmureanu, C. (2016). Special education in the Toronto District School Board: Trends and comparisons to Ontario. [Research Report No. 16/17-06]. Toronto District School Board. https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/research/docs/reports/SpecialEducation%20in%20TDSB%20-%20TrendsComparisons%20to%20Ontario%202009-15.pdf

- Brown, R. S. & Parekh, G. (2013). The intersection of disability, achievement, and equity: A system review of special education in the TDSB. [Research Report No. 12-13-12]. Toronto District School Board. https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/research/docs/reports/Intersection%20of%20Disability%20Achievement%20and%20Equity.pdf

- Collins, K. M., Connor, D., Ferri, B., Gallagher, D., & Samson, J. F. (2016). Dangerous assumptions and unspoken limitations: A disability studies in education response to Morgan, Farkas, Hillemeier, Mattison, Maczuga, Li, and Cook (2015). Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners, 16(1), 4-16. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311582895_Dangerous_Assumptions_and_Unspoken_Limitations_A_Disability_Studies_in_Education_Response_to_Morgan_Farkas_Hillemeier_Mattison_Maczuga_Li_and_Cook_2015

- Connor, D. J., & Cavendish, W. (2017). Sharing power with parents: Improving educational decision making for students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 41(2), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0731948717698828

- Connor, D. J., & Berman, D. L. (2016). A mother’s knowledge: The value of narrating dis/ability in education. European Scientific Journal, ESJ, 12(10), 85- 104.

- Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of Michigan Press.

- Erevelles, N. (2013) Ch. 8: (Im)material citizens: Cognitive disability, race, and the politics of citizenship. In M. Wappett & K. Arndt (Eds.), Foundations of disability studies (pp. 145-176). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gaztambide-Fernández, R., & Parekh, G. (2017). Market “choices” or structured pathways? How specialized arts education contributes to the reproduction of inequality. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25(41), 1-31.

- Graham, L. J., & Slee, R. (2008). An illusory interiority: Interrogating the discourse/s of inclusion. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40(2), 277-293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00331.x

- Hodge, N. (2016). Chapter 10: Schools Without Labels. In R. Mallett, S. Timimi, & K. Runswick-Cole (Eds.), Re-thinking autism: Diagnosis, identity and equality, (pp. 185-203). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Lalvani, P., & Hale, C. (2015). Squeaky wheels, mothers from hell, and CEOs of the IEP: Parents, privilege, and the “fight” for inclusive education. Understanding and Dismantling Privilege, 5(2), 21-41.

- Million, D. (2011). Intense dreaming: Theories, narratives, and our search for home. The American Indian Quarterly, 35(3), 313-333. muse.jhu.edu/article/447049.

- Million, D. (2013). Therapeutic nations: Healing in an age of indigenous human rights. The University of Arizona Press.

- Moore, M & Slee, R. (2012). Chapter 17: Disability studies, inclusive education and exclusion. In N. Watson, A. Roulstone, & C. Thomas (Eds.) The Routledge handbook of disability studies (pp. 225- 239). Routledge.

- Ontario Ministry of Education. (2010). Growing success: Assessment, evaluation and reporting in Ontario schools. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/policyfunding/GrowSuccess.pdf

- Ontario Ministry of Education (2013). Learning for all: A guide to affective assessment and instruction for all students, kindergarten to grade 12. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/general/elemsec/speced/learningforall2013.pdf

- Yergeau, M. (2018). Authoring autism: On rhetoric and neurological queerness. Duke University Press.