The determinants of the relationship between parents with physical disabilities and perinatal services: a scoping review

Les déterminants de la relation entre les parents ayant un handicap physique et les services périnataux : étude de portée

Coralie Mercerat, Ph.D. Candidate, Psychology Department, Université du Québec à Montréal

mercerat [dot] coralie [at] courrier [dot] uqam [dot] ca

Dr. Thomas Saïas, Professor, Psychology Department, Université du Québec à Montréal

thomas [dot] saias [at] uqam [dot] ca

Abstract

Because of recent medical advances and increasing advocacy for the rights of people with disabilities, more and more people with disabilities are becoming parents. Parenthood is considered a fundamental right by the United Nations, and appropriate perinatal services are an important promoting factor for positive parenting experience and practices. Despite this, access to parenthood and access to services is still hindered for parents and future parents with disabilities. This scoping review, based on eighteen (n=18) studies, provides a unique insight into the relationship between parents with physical disabilities and perinatal services. Results suggest that four main determinants influence this relationship: mothers’ needs, professionals’ characteristics, quality of relationship with professionals, and organization of services. Issues related to accessing information and the services themselves were also identified. Finally, a framework for accessibility is presented to better understand how to improve access to appropriate services for parents with physical disabilities.

Résumé

En raison des récents progrès médicaux et de la défense croissante des droits des personnes handicapées, de plus en plus de personnes handicapées deviennent parents. La parentalité est considérée comme un droit fondamental par les Nations Unies, et des services périnataux appropriés sont un important facteur de promotion d’une expérience et de pratiques parentales positives. Malgré cela, l’accès à la parentalité et aux services associés demeure difficile pour les parents et futurs parents handicapés. Cette étude de portée, basée sur dix-huit (n = 18) études, fournit un aperçu unique de la relation entre les parents ayant un handicap physique et les services périnataux. Les résultats suggèrent que quatre principaux déterminants influencent cette relation : les besoins des mères, les caractéristiques des professionnel·les, la qualité des relations avec les professionnel·les et l’organisation des services. Des problèmes liés à l’accès à l’information et aux services eux-mêmes ont également été identifiés. Enfin, un cadre d’accessibilité est présenté pour mieux comprendre comment améliorer l’accès aux services appropriés pour les parents ayant un handicap physique.

Keywords: parents with physical disabilities, positive parenting, perinatal services, accessibility

Introduction

With the development of medical technology and the recognition of the rights of people with disabilities in the last 20 years, an increasing number of men and women with disabilities are becoming parents (Blackford, Richardson, & Grieve, 2000). However, despite the fact that the right to start a family is defended by the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (United Nations, 2006), access to parenthood is still hindered at various levels for people with disabilities (Kirshbaum & Olkin, 2002). Firstly, the literature highlights multiple situations in which parenthood is discouraged for people with disabilities: denial of sexuality (O’Toole, 2002), threat of losing child custody (Preston, 2011) and lack of information from professionals on the possibility of becoming a parent (Lawler, Lalor, & Begley, 2013). Secondly, studies report that physical access is hindered, regarding both physical access to the buildings in which services are provided and access to appropriate equipment for pregnancy monitoring. This last point seems to be an additional burden on the health of women with physical disabilities who are at greater risk of negative complications related to pregnancy and childbirth (Tarasoff, 2015). Finally, people with disabilities continue to experience discrimination, skepticism towards their ability to become parents –from their social circles and from professionals–, and negative attitudes regarding their parenting role (Bergeron, Vincent, & Boucher, 2012; Tarasoff, 2015). In this regard, the National Council on Disability highlighted in 2012 the “persistent, systemic and pervasive” nature of discrimination against parents living with disabilities (National Council on Disability, 2012).

Across the literature, the perinatal period has been considered a keystone period in the transition to parenthood that shapes further parenting experience. In order to enable people with disabilities to fully exercise their right to become parents and to have a positive parenting experience – including parental well-being and positive parenting practices –, adequate perinatal services adapted to their needs are essential. In 1998, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a report setting out ten basic conditions to ensure the quality of perinatal services for women (World Health Organization, 1998). Two of these principles mentioned the importance of holistic perinatal services: taking into account the whole person, including any physical limitations, and family centered perinatal services, taking into account the patient's family environment and partner (Chalmers, Mangiaterra, & Porter, 2001; World Health Organization, 1998). These principles of holistic and family centered services are particularly relevant to the experiences of mothers and future mothers with physical disabilities. Despite the importance of accessible perinatal services, there are still few scientific studies specifically addressing the experiences and needs of parents with physical disabilities.

Based on these observations, the objective of this scoping review is to explore the scientific literature surrounding the relationship between parents with physical disabilities – fathers and mothers –, and perinatal services. The notion of “relationship” in this paper refers to the experience lived by the parents when they have interacted with the services. This study will contribute to a better understanding of this relationship, with the goal of providing accessible and satisfactory perinatal services to parents with disabilities.

Method

The scoping review is a rigorous method of exploring and summarizing literature. This type of literature review is particularly relevant for research questions that have not yet been fully investigated and for areas of research that are still misunderstood. The aim is, through literature exploration, to identify recurring concepts, research gaps and future research directions (Daudt, van Mossel, & Scott, 2013; Pham et al., 2014). The scoping review differs somewhat from the systematic review, for example, in the choice of articles that will be reviewed. Indeed, whereas in a systematic review, the quality of the research is a selection criterion, in this scoping review, we, like Pham et al. (2014), have chosen not to exclude studies based on the quality of the methods. This scoping review was conducted following the five steps recommended by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) in their framework for conducting scoping reviews:

1 – Identifying the research question. The purpose of this scoping review was to answer the following question: what determinants define the relationship between parents with physical disabilities and perinatal services?

2 – Identifying relevant studies. In September 2018, we conducted a literature search in two databases used in the fields of psychology and disability – PsychInfo and Pubmed. Articles published in peer-reviewed journals between 1990 and 2018 were included. In order to identify scientific papers that considered both the fathers’ and mothers’ perspective, and to be as broad as possible regarding the types of physical disabilities and stages of the parenting process (pre-, peri- and postnatal periods), the following search terms were chosen: “*men with physical disab*” OR “physically disabled *men” OR “*men with motor disab*” OR “mother* with physical disab*” OR “physically disabled mother*” OR “mother* with motor disab*" OR "father* with physical disab*" OR “physically disabled father*” OR “father* with motor disab*” OR “parent* with physical disab*” OR “physically disabled parent*” OR “parent* with motor disab*” AND “perinatal” OR “postnatal" OR “pregnancy” OR “childbirth”. By choosing terms as “perinatal”, “postnatal”, “pregnancy” or “childbirth”, we attempted to include perinatal and early childhood services in a broad meaning.

| People | Disabilities | Event |

|---|---|---|

| *men ; mother*, father* ; parent* | with physical disab* ; physically disabled ; with motor disab* | perinatal ; postnatal ; pregnancy ; childbirth |

In this primary research, we worked in collaboration with an occupational therapist researcher and a librarian who helped us identify the appropriate language related to the field.

3 – Study selection. All articles on parents or future parents with physical disabilities (for example pregnant women) were analyzed according to the following inclusion criteria (some of the articles found in the databases were on children with disabilities and were excluded) :

- empirical studies of parents with physical disabilities, i.e parents or future parents (for example pregnant women) had to be the participants. This way, we wanted to have the parents or future parents’ perspective on their experience with perinatal and early childhood services ;

- their children had to be between 0 and 12 years old, as we wanted to have parents of younger children, related to perinatal and early childhood services ;

- parents had to directly mention their experience with perinatal services in the “results” section (experience with perinatal services was not necessarily described as a study objective). The notion of “perinatal care” referred to services named as such in the literature, but was also considered more broadly. Thus, all articles referencing “perinatal care” or “perinatal services” were included, as we wanted to have a maximally inclusive definition of the services surrounding the perinatal period. “Perinatal services” or “perinatal care” could then be separated between care providers (obstetrician and midwife, family doctor and general practitioner, nurse, ultrasound technician, receptionist, anesthesia team, social workers) and the settings in which such services were provided (prenatal class, labor/delivery room, examination table and weight scale, home services).

Studies that interviewed only parents with intellectual or perceptual disabilities were excluded from this scoping review, as well as studies targeting parents of children with disabilities.

4 – Charting the data. Once the articles were selected and analyzed, we extracted the following important information in a table (see table 2): authors, date, country, type of study, methods used, sample (participant characteristics) and the main objectives of the study. This approach gave us an overarching view of the research trends in the field of parents with physical disabilities and perinatal services.

5 – Collating, summarizing and reporting the results. In order to systematically summarize the material from the 18 articles, we analyzed the “results” section of each selected study using a qualitative content analysis inspired by Braun and Clark’s process (2006): searching for themes, reviewing themes, naming and refining those themes. This process allowed us to bring to light four salient themes: parents’ needs, professionals’ characteristics, direct relationship with professionals, and organization of services.

Results

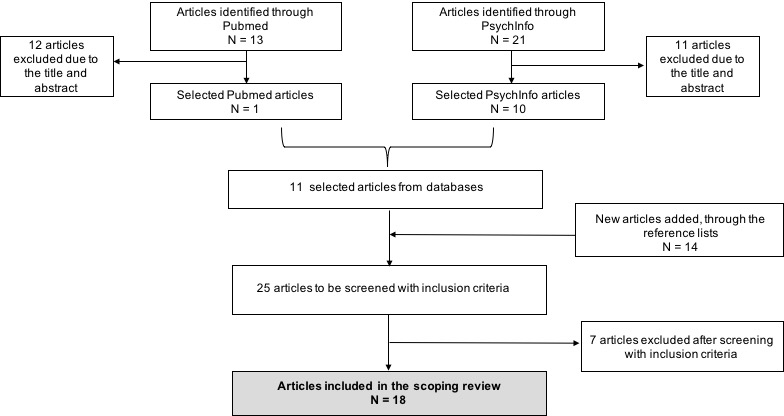

From database searches, we obtained 21 results from Psychinfo and 13 results from Pubmed. After removing articles based on titles and abstracts, 10 articles from Psychinfo and 1 article from Pubmed were selected. We then carefully analyzed the reference list of the remaining 11 articles to find other articles related to our subject. Fourteen other articles were added after reading titles and abstracts. Following the analysis of all articles, 18 articles met the inclusion criteria and are presented in this scoping review.

Figure 1 : flow diagram for selection of articles

We collected articles dated from 1997 to 2017. However, most of the studies took place after 2010 (n=13). One study was conducted in Austria, eight in the United States, four in Canada, four in United Kingdom and one in New Zealand. Of the 18 selected studies, a large majority followed a qualitative design (n=15), mostly using semi-structured interviews and in some cases, focus-groups. The quantitative studies (n=3) used questionnaires or file reviews.

Despite our attempt to include both fathers’ and mothers’ perspectives in this scoping review, only one study (Kaiser, Reid, & Boschen, 2012) concerned both parents. Seventeen of the 18 studies selected for the scoping review considered only mothers or future mothers with physical disabilities.

Studies mainly focused on the experience of women with physical disabilities and their personal perspectives on pregnancy, labor, anesthesia, childbirth and childcare. Some studies were more specific and focused on women’s experience with prenatal care.

Table 2: describes the objectives of each study # Authors (date) Country Type Methods Sample Objectives 1 Thomas & Curtis (1997) United Kingdom Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 17 women with a wide range of impairments at different stages in their reproductive journey To explore some of the social barriers disabled women face when they consider having a child, become pregnant, come into contact with maternity and related services, and become mothers 2 Blackford et al. (2000) Canada Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 8 mothers with various chronic illnesses To obtain a description of maternity experiences of mothers with chronic illnesses 3 Lipson & Rogers (2000) USA Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 12 mothers with mobility-limiting physical disabilities To examine the pregnancy, birth and postpartum experiences of women with mobility-limiting physical disabilities 4 Prilleltensky (2003) Canada Qualitative Focus-groups and interviews 35 women with disabilities To explore the experiences of mothers with physical disabilities 5 Gavin et al. (2006) USA Quantitative Files review 2740 pregnant women with various types of disabilities in 4 U.S. states To investigate differences in health service use and pregnancy outcomes among women enrolled in Medicaid under eligibility categories for blind and disabled and those enrolled under other eligibility categories 6 Kaiser et al. (2012) Canada Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 12 parents (6 mothers and 6 fathers) with spinal cord injury To understand the experiences of parents with spinal cord injury and their use of aids and adaptations in caring for their young children 7 Tebbet & Kennedy (2012) United Kingdom Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 8 mothers with spinal cord injury To examine the lived experiences of pregnancy and childbirth in women with spinal cord injury 8 Walsh-Gallagher et al. (2012) United Kingdom Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 17 pregnant women with different types of disabilities To discover the personal meanings that pregnant women with a disability ascribe to their pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood experiences 9 Redshaw et al. (2013) United Kingdom Quantitative 12 pages questionnaires 1 842 women with various types of disabilities To describe the maternity care provided during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period for women with a disability

To explore disabled and non-disabled women’s perceptions of care received during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period

To describe the maternity care provided during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period for women with a disability To explore disabled and non-disabled women’s perceptions of care received during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period To compare the care and perceptions of care received of women with different types of disabilities with those of women with no disclosed disability

10 Payne et al. (2014) New Zealand Qualitative Individual and focus-group interviews 62 mothers with either a physical or a sensory impairment To identify ways for services to be more responsive for women living with physical or sensory impairments during and after pregnancy 11 Iezzoni et al. (2015) USA Qualitative Semi-structured, open-ended interviews 22 mothers with physical disabilities To gather preliminary information about experiences of women with mobility disabilities in accessing routine prenatal services 12 Mitra et al. (2016) USA Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 25 mothers with physical disabilities To provide an in-depth examination of unmet needs of women with physical disabilities during pregnancy and childbirth 13 Smeltzer et al. (2016) USA Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 25 mothers with physical disabilities To explore the perinatal experiences of women with physical disabilities and their associated recommendations for maternity care clinicians to improve care 14 Long-Bellil et al. (2017) USA Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 25 mothers with physical disabilities To explore the experiences of women with physical disabilities regarding pain relief during labor and delivery, with the goal of informing care 15 Mitra et al. (2017) USA Quantitative Survey on maternity care access and experiences of women with physical disabilities,/td> 126 mothers with physical disabilities To examine the pregnancy and prenatal care experiences and needs of U.S. mothers with physical disabilities and their perceptions of their interactions with their maternity care clinicians 16 Schildberger et al. (2017) Austria Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 10 mothers with motor and sensory impairments To investigate the personal meanings and experiences of women with disabilities in regard to pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium 17 Smeltzer et al. (2017) USA Qualitative Semi-structured interviews 22 mothers with significant mobility disabilities To explore labor, birth, and anesthesia experiences of women with physical disabilities 18 Tarasoff (2017) Canada Qualitative In-depth interviews 13 mothers with physical disabilities To understand the perinatal care experiences and outcomes of women with physical disabilities, with an emphasis on identifying barriers to care

The thematic analysis revealed four main themes related to parent-professional relations in this specific context. Results are presented with an ecological perspective, i.e. from the personal perspective to a more systemic level: mothers’ needs, characteristics of professionals, the direct relationship with professionals, and the organization of services. The emerging themes allowed us to determine the extent to which the needs of mothers are met by the services offered by obtaining information both about mothers’ needs and about available services.

Studies describe mainly negative or unsatisfactory experiences among their participants. In the following section, a conscious effort has been made to include both negative and positive experiences when they have been presented, in order to paint a picture that accurately characterizes the studies’ results.

Mothers' needs

Few studies have specifically focused on mothers’ needs related to the perinatal services. However, results highlighted that the mothers’ needs were related to obtaining more information (Mitra et al., 2017; Mitra, Long-Bellil, Iezzoni, Smeltzer, & Smith, 2016; Prilleltensky, 2003; Thomas & Curtis, 1997), particularly about the impact of disability on pregnancy and delivery, about access to resources, and about labor and delivery. Women also expressed a desire to participate in the decision-making process (Smeltzer, Wint, Ecker, & Iezzoni, 2017) and to be able to plan in advance, in order to be informed throughout the process (Payne et al., 2014). A woman in Prilleltensky’s study (2003) also reported a greater need for practical support rather than emotional support.

Professionals' characteristics

Several characteristics of professionals working with these mothers were noted in the studies. Firstly, a lack of knowledge and experience of the professionals was reported in many studies (Lipson & Rogers, 2000; Long-Bellil, Mitra, Iezzoni, Smeltzer, & Smith, 2017; Mitra et al., 2016; Schildberger, Zenzmaier, & König-Bachmann, 2017; Smeltzer, Mitra, Iezzoni, Long-Bellil, & Smith, 2016; Smeltzer et al., 2017; Tarasoff, 2017; Walsh-Gallagher, Sinclair, & Mc Conkey, 2012). For example, one professional had no knowledge regarding conception and disability (Mitra et al., 2016), and nurses did not know how to offer alternatives to women, particularly regarding the use of equipment for nursing, childcare, and more (Lipson & Rogers, 2000). Some participants also reported inaccurate knowledge on the part of professionals, for example about the feeling of contractions or the feeling of pain for people with physical disabilities (Smeltzer et al., 2017). On some occasions, women reported that professionals had expressed concern that the mother may transmit her disability to her child or that pregnancy and childbirth may affect the mother's health (Mitra et al., 2017; Schildberger et al., 2017).

In addition, some women reported negative and skeptical attitudes or stereotypes (Blackford, Richardson, & Grieve, 2000; Lipson & Rogers, 2000; Mitra et al., 2017; Payne et al., 2014; Tarasoff, 2017), a lack of sensitivity (Lipson & Rogers, 2000; Schildberger et al., 2017), and negative or shocked reactions from professionals (Mitra et al., 2017; Walsh-Gallagher et al., 2012). Mothers reported that some professionals perceived women with physical disabilities as asexual or unable to care for their children (Mitra et al., 2017, 2016; Smeltzer et al., 2017; Tarasoff, 2017).

Direct relationship with professionals

The “direct relationship with professionals” theme refers to the relationship that women developed with healthcare providers (gynecologist, nurses, medical staff, for example) during the perinatal period.

There was a lack of consensus among women about their experiences, with some reporting positive perceptions, and others feeling that their needs were not addressed.

Women reported a variety of factors that contributed to positive maternity experiences. For instance, participants appreciated the time professionals took to explain their specific situation and the different options available to them (Payne et al., 2014; Smeltzer et al., 2017). According to one study, women appreciated having their care (e.g. anesthesia) planned in advance with the doctor (Long-Bellil et al., 2017). Women also reported that they appreciated being part of the decision-making process (Tebbet & Kennedy, 2012), especially regarding the form of anesthesia chosen during childbirth (Smeltzer et al., 2017). Other studies have highlighted different contexts in which professionals have demonstrated a willingness to learn more about the interaction between disability and pregnancy (Mitra et al., 2017) and have shown interest in developing more knowledge about the woman and her experience as a mother with disabilities (Prilleltensky, 2003).

Despite these positive instances, the majority of studies have reported mostly negative experiences. Women reported a lack of information shared with them by the professional (Smeltzer et al., 2017; Walsh-Gallagher et al., 2012). They experienced difficulties communicating with the staff (Lipson & Rogers, 2000; Schildberger et al., 2017) and these interactions were sometimes qualified with “fear, awkwardness and uncertainty” (Schildberger et al., 2017). One study even reported that, for one participant, the only way to communicate with the gynecologist was through medical journal articles (Smeltzer et al., 2017).

In two studies, women reported that professionals had encouraged them to terminate their pregnancy (Prilleltensky, 2003; Walsh-Gallagher et al., 2012). Similarly, women reported that they had been challenged in their desire to become mothers (Payne et al., 2014) and had to convince the professionals that they could be pregnant and take care of the infant (Blackford et al., 2000; Payne et al., 2014). Women also reported that they sometimes felt observed or controlled (Schildberger et al., 2017). Three studies have highlighted feelings of being “threatened” by professionals about the risk of giving birth to a disabled child (Lipson & Rogers, 2000; Mitra et al., 2016; Walsh-Gallagher et al., 2012).

Results highlighted a pattern of inadequate care and unmet needs according to mothers. Mothers found that staff were not sufficiently engaged in their care (Redshaw, Malouf, Gao, & Gray, 2013), and some reported feeling “distance” between them and the maternity staff (Tebbet & Kennedy, 2012). They also reported that professionals had been intrusive with home visits, especially when mothers did not request them. They also reported difficulty building deep relationships with home nurses, as they changed regularly (Prilleltensky, 2003). Finally, one study reported that participants feared visitors, as they were concerned about losing custody of their child (Walsh-Gallagher et al., 2012).

In terms of medical options for childbirth, women feared being pressed to choose C-section, as the gynecologist sometimes strongly recommended this intervention (Smeltzer et al., 2017). Anesthesia was also a problem for some expectant mothers, as they expressed concern that the anesthesia staff underestimated the complexity of their situation (Smeltzer et al., 2017).

Finally, studies have highlighted that professionals sometimes failed to acknowledge the specific needs of their patients living with disabilities (Iezzoni, Wint, Smeltzer, & Ecker, 2015; Lipson & Rogers, 2000), especially after birth (Walsh-Gallagher et al., 2012), and a lack of consideration of women’s expertise on their own experience and body (Smeltzer et al., 2017; Tarasoff, 2017). One study found that professionals did not always recognize the importance of disability, focusing either on the baby or on pregnancy (Lipson & Rogers, 2000), without taking into account the situation of women as a whole.

Organization of services

The “organization of services” is an important theme that emerged throughout the scoping review. It refers to the way services are organized and the level of care, as perceived by participants. It appeared that women with and without disabilities were unevenly served in terms of timeliness of intervention and adequacy of maternity services (Gavin, Benedict, & Adams, 2006).

Women with disabilities reported that they did not receive enough professional support during pregnancy and childbirth (Schildberger et al., 2017), and also with breastfeeding (Lipson & Rogers, 2000) or with helping to care for the baby (Thomas & Curtis, 1997). Women also reported receiving contradictory advice from professionals (Thomas & Curtis, 1997), particularly on breastfeeding (Prilleltensky, 2003).

Two studies reported a lack of communication between professionals (Lipson & Rogers, 2000; Tarasoff, 2017). The participants feared having their information lost in the file transfer from one department to another (Thomas & Curtis, 1997). Women also noted that professionals did make not enough referrals (Lipson & Rogers, 2000), despite their needs as mothers or future mothers with physical disabilities.

With regard to information sharing, some studies revealed barriers to accessing information about certain health care services, pain management (Long-Bellil et al., 2017) or educational resources, as prenatal classes were not accessible to individuals with disabilities (Blackford et al., 2000). The use of the Internet, as well as experience sharing with other mothers with disabilities, were considered valuable sources of information for mothers with physical disabilities (Kaiser et al., 2012; Mitra et al., 2016), as it was otherwise difficult to find resources that met their particular needs.

Participants in three studies reported a lack of financial assistance (Blackford et al., 2000; Kaiser et al., 2012; Prilleltensky, 2003). One study reported that some participants only had access to services covered by insurance (Schildberger et al., 2017). However, another study pointed out that mothers with disabilities were more likely to be covered by insurance, compared to mothers without disabilities (Gavin et al., 2006).

Six studies reported challenges experienced by participants in accessing equipment – either pregnancy monitoring equipment or the equipment to care for their baby – and to the services themselves (e.g. the building, the maternity, the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or the parking lot) that were not accessible (Iezzoni et al., 2015; Lipson & Rogers, 2000; Mitra et al., 2017, 2016; Tarasoff, 2017; Thomas & Curtis, 1997). The babies and mothers were sometimes separated when the baby was in the NICU (Walsh-Gallagher et al., 2012). One study even reported that NICU services were not adapted, for example, for non-sterile wheelchairs (Tarasoff, 2017). In addition, women reported difficulties when they were registered in two wards: disability-oriented wards and maternity wards. For instance, they were concerned about disturbing other patients when their baby was crying in the disability-oriented ward and there were no other babies in that ward (Tebbet & Kennedy, 2012).

Finally, one study reported the uniformity and lack of flexibility in care arrangements (Thomas & Curtis, 1997). Because of their disability, women had limited choices, for instance regarding their position during labor (Redshaw et al., 2013). In addition, one study directly mentioned the birth process as highly medicalized and technologized even though mothers had a desire for a more natural birth (Lipson & Rogers, 2000). Another study mentioned the presence of many professionals in the labor room, as if it was a spectacle, according to the perception of parturient women (Walsh-Gallagher et al., 2012).

Discussion

The purpose of this article was to provide an overview of the determinants influencing the relationship between parents with physical disabilities and perinatal services. Our scoping review reveals that this relationship is influenced by four main determinants, ranging from personal to systemic in nature: mothers’ needs, professionals’ characteristics, direct relationship with professionals and organization of services. This scoping review includes data from several countries with different socio-political contexts and care structures. Despite the differences that exist between countries - particularly in terms of costs and reimbursement of services, which seem to be a particular issue in the Unites States - the findings of this study are rather consistent across the countries.

The results of this scoping review highlight several factors that can contribute to positive experiences pursuing parenthood for individuals living with a disability. When professionals were willing to learn more about their patients’ situation, were eager to listen to their needs and to provide details on the situation, and were willing to plan the medical process in advance, the experience was perceived more positively by parents (Schildberger et al., 2017). A study noted that women had a positive experience when they were able to advocate for themselves to the medical team (Lipson & Rogers, 2000).

On the other hand, negative factors – for instance discriminatory attitudes – can increase stress and complications during childbirth and decrease feelings of self-confidence and self-efficacy (Schildberger et al., 2017). In order to promote optimal child development and positive parenting practices, efforts should be made to improve mothers’ experiences with maternity services, especially when they have additional needs.

Adequate perinatal services are an important support for parents with physical disabilities, can protect against child maltreatment and can enable people with disabilities to fully embrace their parenting role. Hence, an effort should be made to enhance the accessibility of these services. To further our understanding of accessibility and to analyze the relation between identified needs and service provision, the framework developed by Dixon-Woods et al. (2006) on accessibility of the health care by disadvantaged people was employed. This framework has allowed us to describe the accessibility of perinatal services for these parents in a dynamic way, considering the concept of accessibility more broadly than just a lack of access to equipment and physical environment reported in the results. Although this model is the result of a systematic review of the literature on access to health services only, we have used it in a broader context that includes both health services and community services. Since this model describes the process of accessing a service, it seems appropriate to extrapolate it to other types of services. Six dimensions compose this framework by which an individual can determine if a service will meet his/her needs.

Firstly, the concept of “candidacy” is defined as “the ways in which people's eligibility for medical attention and intervention is jointly negotiated between individuals and health services” (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006, p. 7). The identification of candidacy refers to the way people recognize their symptoms and medical care needs. One of the main barriers to quality services that meet parents’ needs revealed by our scoping review is related to a lack of information found in the four determinants of the relationship between parents with physical disabilities and perinatal services. Such observations are consistent with previous articles of similar interest (see for example Tarasoff, 2015). Access to information on various topics – from available resources to the medical impact of disability on pregnancy, labor and childbirth – was an important need identified by parents with physical disabilities throughout the selected articles. The lack of information and inaccuracy of information were pointed out as characteristic of some professionals, and as an issue in the relationship between parents with physical disabilities and professionals. Participants mentioned frequently having difficulty obtaining information or sharing their expertise on their own situation with the medical team.

The second dimension described by Dixon-Woods et al. (2006) is “navigation”. It encompasses two parts. The first is the awareness that the service is actually being offered. In that regard, the result of our scoping review highlighted that a lack of information was common within the organization of services, as it was sometimes difficult for parents to obtain information about the existence of certain services. The second part concerns the more practical aspects of accessing the service, such as transport. This was underlined in our results in the identified lack of physical accessibility not only to equipment, but also to the services themselves (e.g. the NICU or the parking lot) (Iezzoni et al., 2015; Lipson & Rogers, 2000; Mitra et al., 2017, 2016; Schildberger et al., 2017; Tarasoff, 2017; Thomas & Curtis, 1997).

The third dimension is related to the “permeability of services”, which refers to the “ease with which people can use services” (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006, p. 7). This dimension refers to the flexibility of the service and to the parents’ satisfaction with it, which affects the parents’ choice to use it or not. Our scoping review allows us to highlight, for instance, non-homogeneous advice from the professionals, lack of alternatives available for delivery, and a lack of adapted advice or equipment unique to these parents’ needs to allow them to take care of their children (breastfeeding, bathing, for example) (Lipson & Rogers, 2000; Thomas & Curtis, 1997). On the contrary, women reported more satisfying experiences when professionals made accommodating arrangements and took time to explain the situation and the different options available in terms of delivery (Smeltzer et al., 2017).

The fourth dimension is “appearance at health services”. It refers to the individual’s ability to advocate for themselves and to claim the services they need. This is reflected in several studies underlining mothers’ desire to be part of the decision-making process (Redshaw et al., 2013; Smeltzer et al., 2017; Tebbet & Kennedy, 2012), including, for example, having the autonomy to choose the method of delivery, as some women mentioned feeling pressed by the medical team to opt for a C-section (Smeltzer et al., 2017). Another example is brought by Mitra et al. (2017) in their study on maternity care access and experiences of women with physical disabilities. Results of this study show that 46% of their participants met with several healthcare providers before selecting one who would meet their needs.

The fifth dimension – “adjudications ” – concerns the professionals themselves, and the instances of prejudice or negative judgement women perceived from them. Throughout our scoping review, we noted that participants experienced various negative or stereotypical remarks from professionals. This is congruent with previous studies (see for example Bergeron, Vincent, & Boucher, 2012; Killoran, 1994). The main judgments or stereotypes identified in those studies surrounded professionals encouraging mothers to terminate pregnancy. Authors also described negative attitudes or shocked reactions following the pregnancy announcement.

The final dimension, “offers and resistance”, refers to the result of the negotiation between individuals and healthcare system about their eligibility for services. Individuals may choose to refuse a service because it does not meet their needs. Blackford et al.’s (2000) study on prenatal education showed that some pregnant women with disabilities chose to not attend prenatal class, because such classes did not address their concerns and were not oriented towards their situation. Despite this example, this scoping review does not allow for a conclusion to be made regarding this last dimension. Further research, focusing more precisely on accessibility, could bring to light some interesting elements concerning the choice of parents with physical disabilities to use – or not – a certain service.

Limits and strengths of the scoping review

Analyzing the relationship between parents with physical disabilities and perinatal services through the six dimensions presented above has enabled us to highlight opportunities for intervention at the levels of parents, professionals and decision-makers regarding the structure and provision of services.

Although conducted in a systematic and rigorous manner, this scoping review has several limitations. First, our research was limited to empirical studies written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals. As we focused specifically on the state of published scientific research about parents with physical disabilities and perinatal services, our criteria eliminated other relevant texts presenting the experiences of parents with physical disabilities regarding perinatal services, for example, barriers to accessibility (see for example Begley et al., 2009 or Morris & Wates, 2006). Second, the choice of search terms may have had an impact on the selection of studies as this study is more exploratory in its nature. We remained vague in defining the disabilities that would be included in our research. Some specific disabilities could have been rejected from our corpus, such as articles dealing specifically with spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis. For these reasons, results should be considered cautiously, as they represent only a partial amount of what is written about parents with physical disabilities and their experience with perinatal services. Third, we limited our search to people who were already parents or expecting. However, people who were looking to become parents or young parents who lost their child before term or soon after birth may also have been in contact with perinatal services. To our knowledge, no research has examined these parents or prospective parents in particular, unfortunately excluding them from our sample. Research focusing specifically on this population should be conducted to understand the importance of perinatal services in contexts where access to parenting may be difficult, and in experiences of tragedy or loss regarding parenthood.

General observations and future orientations

In summary, various general observations on the state of research in the field can be highlighted and research directions should be taken into account, in the near future. First, the results mainly described negative or unsatisfactory experiences of mothers with various physical disabilities. However, some results also showed that some situations were more supportive of mothers with physical disabilities, particularly contexts where professionals showed a desire to learn and listen to the mothers’ experience and expertise towards their body. There is a need for further research, with a greater emphasis on positive experience, in order to discover best practices in meeting the needs of parents with physical disabilities and to enhance the experience for both parents and professionals. Second, this scoping review appears to be representative of a sample of other publications – scientific or grey literature – on parents with physical disabilities: when it comes to talk about parenting, women are the ones who participated mostly in these studies. Research involving mostly fathers or as many fathers as mothers is still underrepresented in the scientific literature (see for example Bergeron, Vincent, & Boucher, 2012). To promote a more inclusive approach, we need to know more about the situation of fathers with physical disabilities, their parental experience, their parenting role and their needs as parents. Third, most of the articles focused on prenatal and perinatal maternity care. However, once women have given birth, very little information is available regarding their needs and the type of services they received in the postnatal period. In this regard, research should be conducted on the care needs of parents with physical disabilities during the early childhood period. Indeed, several types of services could be important to supporting parents at this stage of their parenting, including home support services (households and groceries), adapted transportation, and accessible daycare centers and schools. Further research should therefore focus on these types of services. Finally, this scoping review brought together studies from the past 20 years and from different countries. Few differences can be highlighted in the results for the various countries and over the last 20 years. A brief overview on the “discussion section” of the 18 studies selected for this paper allows us to state that the recommendations given in the articles, which mainly refer to the training of professionals, have remained mostly static. After 20 years of research and homogeneous recommendations, further research – if we still need further research – should focus on the reasons why such few efforts were made to improve the experiences of parenthood for parents with physical disabilities, in relation to perinatal services.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Samantha Kargakos and Rachel Goldfarb for the English revision, Evelina Pituch for her assistance in identifying appropriate search terms, and Luc Dargis, for his advice on systematic scoping reviews. No conflicts of interests are to be declared. We are also deeply grateful to the advisory board for their support and communication that have made this work more grounded in their realities.

References

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Begley, C., Higgins, A., Lalor, J., Sheerin, F., Alexander, J., Nicholl, H., … Kavanagh, R. (2009). Women with disabilities: Barriers and facilitators to accessing services during pregnancy, childbirth and early motherhood. Dublin: School of Nursing ans Midwifery, Trinity College.

- Bergeron, C., Vincent, C., & Boucher, N. (2012). Experience of parents in wheelchairs with children aged 6 to 12. Technology and Disability, 24(4), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.3233/TAD-120356

- Blackford, K. A., Richardson, H., & Grieve, S. (2000). Prenatal education for mothers with disabilities. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(4), 898–904. https://doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01554.x

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706 qp063oa

- Chalmers, B., Mangiaterra, V., & Porter, R. (2001). WHO principles of perinatal care: The essential antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum care course. Birth, 28(3), 202–207.

- Daudt, H. M., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- Dixon-Woods, M., Cavers, D., Agarwal, S., Annandale, E., Arthur, A., Harvey, J., … Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35

- Gavin, N. I., Benedict, M. B., & Adams, E. K. (2006). Health service use and outcomes among disabled Medicaid pregnant women. Women’s Health Issues, 16(6), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2006.10.003

- Iezzoni, L. I., Wint, A. J., Smeltzer, S. C., & Ecker, J. L. (2015). Physical accessibility of routine prenatal care for women with mobility disability. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(12), 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5385

- Kaiser, A., Reid, D., & Boschen, K. A. (2012). Experiences of parents with spinal cord injury. Sexuality and Disability, 30(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-011-9238-0

- Killoran, C. (1994). Women with disabilities having children: It’s our right too. Sexuality and Disability, 12(2), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02547886

- Kirshbaum, M., & Olkin, R. (2002). Parents with physical, systemic, or visual disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 20(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1023/ A:1015286421368

- Lawler, D., Lalor, J., & Begley, C. (2013). Access to maternity services for women with a physical disability: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Childbirth, 3(4), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1891/2156-5287.3.4.203

- Lipson, J. G., & Rogers, J. G. (2000). Pregnancy, birth, and disability: Women’s health care experiences. Health Care for Women International, 21(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/073993300245375

- Long-Bellil, L., Mitra, M., Iezzoni, L. I., Smeltzer, S. C., & Smith, L. D. (2017). Experiences and unmet needs of women with physical disabilities for pain relief during labor and delivery. Disability and Health Journal, 10(3), 440–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.02.007

- Mitra, M., Akobirshoev, I., Moring, N. S., Long-Bellil, L., Smeltzer, S. C., Smith, L. D., & Iezzoni, L. I. (2017). Access to and satisfaction with prenatal care among pregnant women with physical disabilities: Findings from a national survey. Journal of Women’s Health, 26(12), 1356–1363. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh. 2016.6297

- Mitra, M., Long-Bellil, L. M., Iezzoni, L. I., Smeltzer, S. C., & Smith, L. D. (2016). Pregnancy among women with physical disabilities: Unmet needs and recommendations on navigating pregnancy. Disability and Health Journal, 9(3), 457–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.12.007

- Morris, J., & Wates, M. (2006). Supporting disabled parents and parents with additional support needs. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- National Council on Disability. (2012). Rocking the cradle: Ensuring the rights of parents with disabilities and their children. Washington: Author. Retrieved from https://ncd.gov/publications/2012/Sep272012/

- O’Toole, C. (2002). Sex, disability and motherhood: Access to sexuality for disabled mothers. Disability Studies Quarterly, 22(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq. v22i4.374

- Payne, D. A., Guerin, B., Roy, D., Giddings, L., Farquhar, C., & McPherson, K. (2014). Taking it into account: Caring for disabled mothers during pregnancy and birth. International Journal of Childbirth, 4(4), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1891/2156-5287.4.4.228

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

- Preston, P. (2010). Être parent avec des incapacités. In J. H. Stone & M. Blouin (Eds), International encyclopedia of rehabilitation. Buffalo: Center for International Rehabilitation Research Information and Exchange.

- Prilleltensky, O. (2003). A ramp to motherhood: The experiences of mothers with physical disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 21(1), 21–47. https://doi.org/10. 1023/A:1023558808891

- Redshaw, M., Malouf, R., Gao, H., & Gray, R. (2013). Women with disability: The experience of maternity care during pregnancy, labour and birth and the postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(1), 174. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-174

- Schildberger, B., Zenzmaier, C., & König-Bachmann, M. (2017). Experiences of Austrian mothers with mobility or sensory impairments during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1388-3

- Smeltzer, S. C., Mitra, M., Iezzoni, L. I., Long-Bellil, L., & Smith, L. D. (2016). Perinatal experiences of women with physical disabilities and their recommendations for clinicians. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 45(6), 781–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2016.07.007

- Smeltzer, S. C., Wint, A. J., Ecker, J. L., & Iezzoni, L. I. (2017). Labor, delivery, and anesthesia experiences of women with physical disability. Birth, 44(4), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12296

- Tarasoff, L. A. (2015). Experiences of women with physical disabilities during the perinatal period: A review of the literature and recommendations to improve care. Health Care for Women International, 36(1), 88–107. https://doi.org/10. 1080/07399332.2013.815756

- Tarasoff, L. A. (2017). "We don’t know. We’ve never had anybody like you before": Barriers to perinatal care for women with physical disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 10(3), 426–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.03.017

- Tebbet, M., & Kennedy, P. (2012). The experience of childbirth for women with spinal cord injuries: An interpretative phenomenology analysis study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(9), 762–769. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.619619

- Thomas, C., & Curtis, P. (1997). Having a baby: Some disabled women’s reproductive experiences. Midwifery, 13(4), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-6138 (97)80007-1

- United Nations. (2006). Convention relative aux droits des personnes handicapées et protocole factultatif. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/ convention/convoptprot-f.pdf

- Walsh-Gallagher, D., Sinclair, M., & Mc Conkey, R. (2012). The ambiguity of disabled women’s experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood: A phenomenological understanding. Midwifery, 28(2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.midw.2011.01.003

- World Health Organization. (1998). Workshop on perinatal care. Venice, April 16-18, 1998. Copenhagen: Author. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/ handle/10665/108098/E60220.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y