Healing House I: A Material Phenomenology of Illness

Maison de guérison I : Une phénoménologie matérielle de la maladie

Darian Goldin Stahl, PhD, MFA

Affiliation: Concordia University

Contact Information:

#15 1699 Rue Rachel Est

Montreal, QC H2J 2K6

438-922-5316

dariangoldinstahl [at] gmail [dot] com

Abstract

This paper is a deep investigation into one art installation, Healing House I, which materializes the lived experience of being diagnosed with a chronic illness. This artwork is part of a collaborative project between artist Darian Goldin Stahl and her sister, Devan Stahl, who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Together, they use a phenomenological methodology to express the disconnections between the lived body and the body object that can occur after a diagnosis, as well as the conditions necessary to mend this separation. Joining fleshy material, sound, vibration, and scent in this artwork, Goldin Stahl analyses how a multi-sensory and artistic interpretation of her sister’s illness narratives can tacitly communicate one experience of living with MS. In sharing this artwork with others in a disability arts exhibition, the sisters aim towards fostering a collective, intercorporeal understanding and empathy for the ill body.

Résumé

Cet article est une enquête approfondie sur une installation artistique intitulée Maison de guérison I qui matérialise l’expérience vécue de recevoir un diagnostic de maladie chronique. Cette œuvre d’art fait partie d’un projet de collaboration entre l’artiste Darian Goldin Stahl et sa sœur, Devan Stahl, qui a reçu un diagnostic de sclérose en plaques. Ensemble, elles utilisent une méthodologie phénoménologique pour exprimer les déconnexions entre le corps vécu et le corps objet qui peuvent survenir après un diagnostic ainsi que les conditions nécessaires pour réparer cette séparation. Alliant dans cette œuvre la matière charnue, le son, les vibrations et le parfum, Goldin Stahl analyse la manière dont une interprétation multisensorielle et artistique des récits de maladie de sa sœur peut communiquer tacitement l’expérience de la vie avec la sclérose en plaques. En partageant cette œuvre avec d’autres dans le cadre d’une exposition sur l’art du handicap, les sœurs visent à promouvoir une compréhension et une empathie collectives et intercorporelles du corps malade.

Keywords: Illness, Research-Creation, Fine Art, Senses, Collaboration, Phenomenology, Subjectivity

Introduction

This paper describes the formation of a relational understanding of one’s illness through the collaborative research-creation project, Healing Houses, which was exhibited as part of the “VIBE Symposium” in December 2018. The central question motivating the creation of the artwork asks, “If flesh is the site of subjectivity and intercorporeality, what happens to the ill person’s conception of self when ossifying biomedical imaging technologies become the primary method of visualizing disease?” Drawing from a phenomenological understanding of bodily unease put forth by philosophers like Havi Carel and Elaine Scarry, I aim to materialize my sister’s experience of diagnostic medical scanning as a multi-sensory and participatory installation. This creative re-interpretation becomes a method of bridging subjective experience, objectifying MRI scans, and how others may understand one person’s illness. By merging skin, vibration, sound, scent, and viewer interaction into a subjective piece of art, Healing House I forms a phenomenological interpretation of another’s lived experience to foster relational meanings surrounding the ill body.

Healing Houses

Healing Houses is the latest iteration of my long-term collaborative art practice with my sister, Devan Stahl, who is a hospital chaplain, Professor of Medical Ethics at Baylor University, and was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2008 at the age of 22. After months of medical testing to find an underlying cause of her extreme fatigue and the numbness that ran intermittently up her legs, it took a neurologist only a glance at her MRI scans to declare a diagnosis of MS. Instead of helping my sister understand what he saw in those pixelated black and white images of her brain and spine, he declared, “I’m an expert. I know what I am looking for,” while pushing a box of tissues her way (Stahl 2017, p. 6).

For the first few years after my sister’s diagnosis, I found it impossible to speak directly about her illness. In my attempt to make everything seem “fine,” I chose not to talk about her new identity as a woman with disease. Because the pain of her diagnosis was too difficult to acknowledge directly, I began making artwork about Devan’s symptoms and sharing them with her. In this way, I was able to show her my care in a way that my words had failed. This artistic gesture inspired Devan to write more narratives about her experiences with medicine, and then procure a copy of her MRI scans to share with me. She thought I could use these scans to artistically reimagine what it means to view and experience illness, and by sharing this artwork, demonstrate for others a way of materializing their own subjectivity within artwork as well.

Our interdisciplinary partnership begins with Devan writing her first-person narratives on the patient experience, which I then interpret and materialize as artwork. Next, Devan re-interprets this artwork with new layers of meaning from her background in divinity and medical ethics, which may then act as a springboard for my next artwork. By visualizing Devan’s narratives using her MRI scans, Devan attests, “Rather than using an image to set me apart, to brand me as other or object, her [artwork] brings our bodies together. This [artwork] represents my experience of illness, it is a whole-body experience—sometimes cold and alienating, but sometimes radiant and mysterious” (2019, p. 256). Within this cyclical methodology of writing, making, and interpretation, Devan and I also invite others to layer their own interpretation of this work. It is this layering of meaning that may ultimately form a relational understanding of illness.

The Flesh of the House

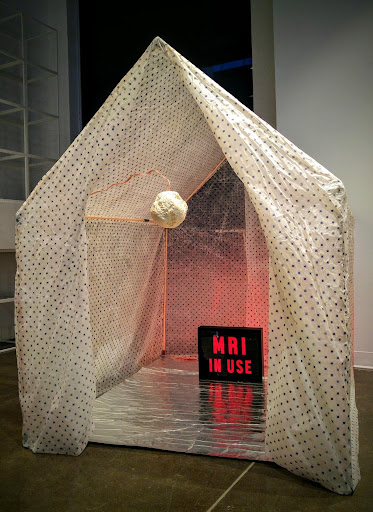

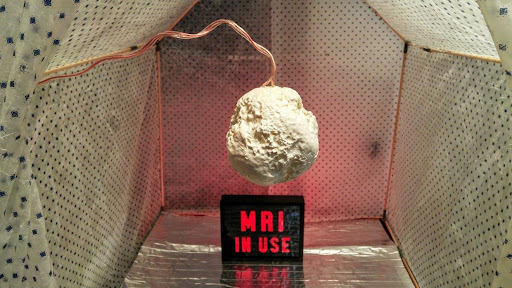

Healing House I is a multi-sensory exploration of what it is like to experience illness through the metaphor of a house. This installation is a person-sized house structure with a triangular pitched roof, reminiscent of a tent. The inner skeleton is made of wooden dowels, and translucent waxed fabric covers the structure to form the walls and roof. The pattern on this fabric consists of small blue florets. The flaps in the back of the house are tied shut, and the front flaps of the house are open to let us see what resides in this interior space. On the floor is a chrome mat that reflects the bright red light emanating from a “MRI IN USE” light box, which might normally be found in a hospital but is now resting towards the back of the house. In the centre of the entryway hangs a white, misshapen orb about the size of a softball. A thick copper wire curls out of the top of the orb like an umbilical cord and falls away behind the left flap of the entryway.

I chose to metaphorically materialize my sister’s narratives as a house for many reasons. First, I wanted to abstract her experience. Because, as Professor of Philosophy Havi Carel explains, “the purpose of abstraction is to understand that world and then return to it with new sensibilities” (2016, p. 6), sculpturally transforming an illness experience allows others to interpret and layer their own significance. The form of a home generally holds deep importance and brings to mind many associations and memories. This multiplicity of meanings layer onto one another and form a collective understanding, or second-order ‘our experience’ of the house.

For many ill people, it can be nearly impossible to identify with a diagnosis without the use of a metaphor such as a home. In her own experience with cancer, feminist film theorist Jackie Stacey describes the necessity of metaphors to “provide the necessary balm for the psychic pain of the unbearable knowledge” (1997, p. 63), since illness can be too profound to comprehend directly. This can be especially true when the signs of a disease are only known through statistical laboratory findings or disembodied medical scans. The abstracted metaphors we construct thus act as an intermediary stepping-stone between avoidance and authentic being-with. The metaphor of this house provides us with an initial entry point to talk about the difficult topic of illness due to its familiarity and universal significance.

Next, I chose the form of a home because of its close associations with the body. Skin studies scholar Claudia Benthien attests that a house is one of the most pervasive metaphors for the body throughout time and culture, because “the notion of living in the body always turns out to be a discourse about hollow space: the imaginary room created by one’s own skin” (2002, 13-14). The doors of a house have parallel metaphors of orifices and membranes of intake or exhalation. Our sensory organs are the windows through which we can see, hear, and smell what lies beyond the skin. The thickness of our skin reveals our security or vulnerability like the walls of a prison or the flaps of a tent. The wide-open door of Healing House I provides associations with the invasiveness of medical scans and searching the interior body for signs of disease.

Next, I chose the form of a home because of its close associations with the body. Skin studies scholar Claudia Benthien attests that a house is one of the most pervasive metaphors for the body throughout time and culture, because “the notion of living in the body always turns out to be a discourse about hollow space: the imaginary room created by one’s own skin” (2002, 13-14). The doors of a house have parallel metaphors of orifices and membranes of intake or exhalation. Our sensory organs are the windows through which we can see, hear, and smell what lies beyond the skin. The thickness of our skin reveals our security or vulnerability like the walls of a prison or the flaps of a tent. The wide-open door of Healing House I provides associations with the invasiveness of medical scans and searching the interior body for signs of disease.

When we speak of the body as a house, we are analogizing how we sense and bring the outside world into our consciousness, the urge to both express and keep hidden our inner truth, and our need for protection and shelter. In times of illness, the security of the body’s facade has been compromised. The safety of skin is undermined when the inner body has turned against itself in the form of an autoimmune disease like multiple sclerosis. What was once familiar and safe, the body “becomes an obstacle and a threat, instead of my home” (Carel 2016, p. 221). The insecurity of health is materialized in this installation as the inbetweenness of shelter and exposure in its tent construction.

The third reason I chose to portray my sister’s experience of MS as a house is this form’s potential to encapsulate the estrangement of the familiar world in times of illness. In her own lived experience of MS, philosopher S. Kay Toombs describes the unmaking of the one’s world after a diagnosis as the “loss of wholeness, loss of certainty, loss of control, loss of freedom to act, and loss of the familiar world” (1987, p. 229). The loss of the familiar is one of the main impetuses for transforming the experience of illness into a surreal home. In this reimagining, the memories of the clinic are joined with the signifiers of home to express how daily life has changed after a diagnosis.

Professor of English and Aesthetics Elaine Scarry describes a house as “an enlargement of the body: it keeps warm and safe the individual it houses in the same way the body encloses and protects the individual within” (1985, p. 38). In times of pain, however, even the most familiar structure of a house can become unmade. The doors, stairs, and narrow hallways of a home cease to be passageways and instead become obstacles to free movement as Devan imagines the spaces she might not be able to navigate with crutches or a wheelchair. For these reasons, the home is an acute site of tension between continuing her routines in the present and imagining her future with chronic illness.

The final reason for the house-as-body metaphor is to give pain an object of attention. Scarry states that pain is essentially objectless; it is invisible and therefore difficult to describe and relate to others. However, if pain can be abstracted by the imagination and labored into material being, “it is through this movement out into the world that the extreme privacy of the occurrence begins to be sharable, that sentience becomes social and thus acquires its distinct human form” (1994, p. 170). Devan and I create artwork to project the pain of a diagnosis into the world so it may become social instead of private, world-building instead of world-diminishing, and ultimately for one person’s illness to be a lens through which we can collectively reflect on our intersubjective embodiment.

Sensory Engagement

I believe fine art to be one of the most effective ways to create subjective metaphors about lived experiences because it can engage many senses to express multiple ways of knowing. Art transforms medical data, ephemera, and signifiers into auratic objects that allow us to tacitly express difficult memories to others and ourselves. I choose to privilege non-verbal expression in Healing House I so that it can be experienced through the sensing body and communicate the unspeakable. This non-linguistic strategy is important because in times of distress, as I have previously stated, words can be hard to find.

Visually, Healing House I is immediately an ominous structure because of its emanating red light. The translucency of its wax walls causes a wash of red to cast through to its fleshy exterior. One can connote the use of red to mean heat, pain, intensity, or warning. Looking through the entryway, viewers can see the origin of the light as the bright red “MRI IN USE” sign in the back of the home. The MRI machine is a pernicious point of vulnerability in my sister’s patient experience. Its cacophonous claustrophobia, loss of privacy, and galling interactions with its technicians in regard to her female body has caused her much distress. In Devan’s pathography narrative, she recounts an interaction with one radiology technician:

He was an older, slightly grizzly looking man who introduced himself by asking where I bought my bra. In my vulnerable position, I did not immediately ask why he wanted to know. I assumed he was a professional with a point…Regardless, he informed me, a metal underwire, like the metal zipper and button on my jeans, would vibrate during the exam, “which some women rather enjoy.” This comment left me in the rather awkward position of having to decide whether I should leave my clothes on and allow this man to think I was “enjoying” the exam, or take them off and feel cold for the next two hours. (Stahl 2018, p. 2)

The pervasiveness of the bright red light emanating from the “MRI IN USE” sign contextualizes our reason for gathering as a tacit dialogue about alarming diagnostic experiences.

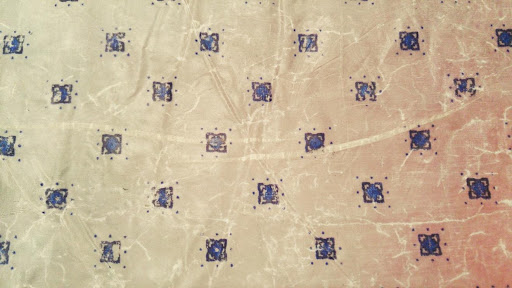

The next sensory engagement of this house is its uncanny, fleshy wallpaper. The walls of the home are constructed from very thin silk that has been dipped in beeswax. My repetitive labour of printing, sewing, folding, storing, and pitching the home has caused wrinkled wear on its points of tension. The weight of the waxed material against its underlying skeleton causes stretching and bunching around its joints like a body’s knees and elbows. The person-sized height and width of the house further the sensation that one is gazing upon an enfleshed body.

The rapid aging of the skin of this home is made more apparent by its wrinkled floret tattoos. This pattern is taken from a standard hospital gown and impressed onto the surface of the material in a transfer printmaking process I developed. Each of the thousands of florets has been printed individually by hand, which gives each one a unique and imperfect character. Because the material is extremely thin and translucent, the pattern can be seen on the exterior and interior views of the walls in equal measure. Merging flesh and hospital gown ensures that the patient cannot hide within her hide, as the tattoos recall the persistent memories of the patient experience, the incurable nature of multiple sclerosis, and the intrusion of symptoms on everyday life.

Approaching the home, viewers will next become aware of the sound of rhythmic, mechanical breathing. The sound is recorded from an idling MRI machine and slowed down to resemble a labored human breath. Upon closer examination, the sound is actually emanating from within the grotesque white orb that hangs in the entryway. Visually, this sculpture appears in a stasis between solid and melting matter. Drips of molten material create crags and valleys in its topography like a biological specimen or celestial body. This milky, melting, and malformed globe is the materialization of the bright white lesions exposed in my sister’s MRI scans.

Viewers are invited to gently touch and hold the orb, only to feel its touch in return. Within the lesion is a vibrational transducer that translates the sound of the breathing MRI machine into a shudder that runs up the arms of every curious examiner. The sense of touch and of being touched has direct implications in the phenomenology of illness. Carel explains that the reversibility of touch is crucial for physicians to view their patients as subjects instead of objects. In an examination, “the oscillation between perceiving myself as a subject that has been objectified (the patient), which is then resubjectified in the act of touching back, continues as long as the intersubjective interaction continues” (Carel 2016, p. 53). It would seem as though touch is the remedy for an objectifying gaze, as the reversibility of touch is a humanity that cannot be denied.

As viewers hold the orb in the doorway and feel its ‘respiration,’ they will also become aware of the pleasant scent of honey. Both the orb and walls of Healing House I are created using raw beeswax, whose scent exhales a perfumed radius around this installation. Cradling the orb close enough to exchange breaths provides a dual sensory caretaking effect of gentle touch and a calming scent of honey.

This aroma can be said to be performing the bygone medicinal practice of healing miasma. Before the general acceptance of germ theory in the late 1800s, the dominant theory for how disease traveled was through miasma, or pathological foul air. To stave off epidemics and disease, air could be cleansed through the introduction of good scents. Although disproved long ago, the attention given to holistic sensory wellbeing is a missing form of healthcare that Healing Houses I provides to those within reach of its honey perfume.

Through the intimate merging of technology and the senses, this installation materializes the call for more holistic healthcare practices. It embodies the need for sensory attention in medicine because to understand this body, one must feel its vibration, hear its rhythm, observe its color, and take in its scent. This is not to say that sensory knowledge is more or less useful than textbook and machine knowledge, but that they are thoroughly entangled. Although my sister’s disease cannot be cured, more attention to her state of well-being could have avoided the distress that her neurologist left during his diagnosis and subsequent abhorrent interactions with radiology technicians.

Towards a Phenomenological Understanding

Phenomenology is useful to describe how Healing House I forms a relational understanding of one person’s illness experience because it focuses on subjective experience. Merleau-Ponty’s description of flesh as “the reversibility of the visible and the tangible” (1968, p. 143) places primary consideration on our qualitative interrelations with the people and things that surround us. Contemporary feminist approaches to phenomenology additionally take into account our memories, identities, environments, and the culture in the formation of flesh. Finally, phenomenology describes how the object body and the lived body can become separated in times of illness, as well as the conditions necessary to mend this separation.

Havi Carel’s The Phenomenology of Illness (2016) examines how the body becomes an object when it no longer cooperates with one’s will—a feeling of disembodiment that is exacerbated when it is objectified by medicine as well. Viewing one’s own medical scans is an alienating experience that leads to one “treating that body as an aberrant object over which one has little control” (Carel 2016, p. 221). Although a patient and her doctor may understand her body as a medical object during an examination, this view is ultimately unsustainable and “ought to be replaced with a more nuanced understanding of intersubjectivity” (Carel 2016, p. 220). I posit that abstracting the singular purpose of MRI scans into artwork is one such strategy for forming intersubjectivity because it opens the possibility for others to layer on their own experiences of inhabiting a body. In this layering of meaning, we can find a common understanding and reflect on the essential aspects of illness and health.

Although I can never truly know how the symptoms of MS feel within Devan’s body, I can form a creative imagining of her experiences by reading her narratives and viewing her scans. After internalizing her voice and the images of her illness, I can then labour to materialize these vestiges as an art form that feels authentic for both of us. We can understand the relational mechanisms at play in this collaboration through phenomenology. Carel theorizes that we can bridge the gap between the first- and third-person perspectives of illness by creating a second-order “‘our life,’ ‘our projects,’ ‘our meaningful activities’” (2016, p. 47), which Devan and I agree that we have effectively accomplished in our collaboration.

Rather than focusing on what has been lost after a diagnosis, Healing House I exemplifies what has been gained, such as the flourishing of our sororal relationship through this artistic collaboration. Scarry attests that creating objects with another person can alleviate their pain by sharing a sense of achievement, “so that the increasingly the pleasure of world-building rather than pain is the occasion of their union” (Scarry 1985, p. 291). Our process allows my sister and me to communicate difficult experiences through the use of a creative stepping-stone, which enables me to show her my deep consideration and care. As Devan reflects, “We live far apart, but I know that nearly every day, my body is on her mind as she lovingly and carefully sits with my image, reads my narratives, and transforms my medical images. By merging her flesh with my flesh, by inhabiting the space of my body, Darian is helping to co-create my image with me, and in so doing we are both transformed” (2019, p. 261).

The potential of this work to form well-being does not end between the two of us. We may spark additional intercorporealities by inviting viewers to engage their bodies in the reading of this work. Materializing illness objects as social artifacts may then also succeed in alleviating the pain of the others who layer their own meanings of illness onto its architecture. By merging our perspectives on illness and sharing them with others in Healing House I, Devan and I call on the viewer to think in line with Carel as she writes, “Although I have no direct access to your pain, I am still able to empathize with it through memory, imagination, or authentic being-with” (2016, 54). Even though this artwork is about one person in particular, its abstraction leaves open the potential for as many interpretations as people who view it. This gathering of subjectivity forms an intercorporeality between subject, maker, and viewer, and allows us to move towards a collective and compassionate understanding of illness.

Intercorporealities

The opportunity to observe how intercorporealities can be formed through artworks like Healing House I came during the VIBE Symposium exhibition. Within the context of disability arts, the gallery attendees were primed to consider these subjective materializations of lived experiences in relation to the symposium’s disability and Deaf activist speakers, as well as in relation to their own sensing bodies. The potential to form these connections with the artwork was also strengthened by the organizers’ mandate to engage the audience through accessible, multi-sensory, and embodied participation.

The first thing I observed was the curiosity around the installation’s materials. The translucency of the fabric seems at odds with the opacity of blue florets. The pattern appears digital or photographic, while the wrinkles evidence distinct corporeal ware. If I were nearby, viewers would ask to touch the mysterious skin-like material of the house. If I was further away or the viewer didn’t know I was the artist, they would touch it anyway. Either way is fine with me, as the alluring flesh of the house calls out to be touched. Additionally, the artwork’s label explicitly invited the audience to touch the luscious satin surface and textured topography of the hanging orb. This suppleness combined with its gentle reverberations creates an engrossing haptic experience. In short, it is a pleasure to touch.

One thing I had not expected when I first installed Healing House I at the VIBE Symposium was that people would enter the structure. In fact, I hung the lesion sculpture in the doorway to block entry and signal that this delicate interior space was off limits. However, I saw many people crouch and crawl under the doorway barrier so they could spend time within this home. Throughout the symposium, even more people approached me to say how much they enjoyed residing in the home. This unexpected level of engagement points to the allure of auratic objects and the desire to feel a sense of homeliness.

As its maker, I understood there to be an enticing tension between this home’s anxious sound and red light and the invitation to explore its otherwise pleasant haptic and olfactory features. For many viewers, on the other hand, the abstraction of the piece opened the possibility to experience the mechanical breath as a comforting, constant rhythm, and the alarming red light to feel like a warming luminescence—proof of the structure’s ultimate ability to evoke multiple interpretations. Once inside, each participant was enveloped by the scent of honey, which constructed an intimate space for the promotion of wellbeing.

When a person accepts the invitation to engage with the installation, an intercorporeality can occur. Intercorporeality here refers to the mutual construction of consciousness between two perceiving bodies: my consciousness is formed not only through my own lived experiences, but also my perception of how others view my body and subjectivity as well (Carel 2016, p. 54). I facilitate intercorporeality between Devan and each viewer when I abstract her body as a house and invite viewers to touch and be touched by this installation. By consciously engaging with the artwork, “those objects in turn become the object of perceptions that are taken back into the interior of human consciousness where they now reside as part of the mind or soul, and this revised conception of oneself… is now actually ‘felt’ to be located inside the boundaries of one’s own skin” (Scarry 1984, p. 256). Once a viewer enters the artwork, the artwork enters a viewer and alters their interior aliveness.

The ultimate goal of this work is not to recreate pain, but to transform and disperse it. With every cycle of translocation in our partnership, from internalized lived experience (subject, Devan), to exterior materialization (artist, Darian) to re-internalized interpretation (Devan & viewers), the original pain of experience is altered and layered with the subjectivity and meaning of others. With the additive process of “each successive recreation, compassion is itself recreated to be more powerful; in the end, it has made real what it at first only passively wanted to be so” (Scarry 1984, p. 291). Phenomenology reveals to us that our subjectivity is never entirely formed by our own perceptions alone, but as a joint venture with the things and people that surround us. As Devan reflects on this work, she states, “In this piece, you are invited to share my burden, which is sometimes physical and often social, and by sharing it, lessen it for me” (2019, p. 265). As we extend our compassion and subjectivities into the objects of creation, we in turn are rebuilt.

Conclusion

While medicine can diagnose and even treat our maladies, it does little to care for psychological impacts of an abrupt life- altering diagnosis, the isolation that often accompanies illness, or the anxiety over an adapted future in an unreliable body. To fill the gap between medicine and wellbeing, embodied art-making practices can provide an opportunity to acknowledge and reflect on the state of our health, which fosters the creative and sensory caretaking that is absent from traditional Western medicine. In the creation and exhibition of artwork on the topics of illness, we can come to understand another’s experience through an embodied engagement. With each new interpretation of this artwork, we are constructing a relational, phenomenological meaning of what it is like to live with illness over a multitude of empathetic identifiers.

Working at the intersection of disability art and biomedical imaging technologies, it becomes clear that both medicine and art seek to make the invisible visible: the truth of the self that can be shared and considered. Instead of only revealing the somatic and diagnosable, Healing House I seeks to show the emotional impacts of illness. This work sensorially communicates both the unease and pleasures of life after a diagnosis. Its uncanniness forces us to reconsider the natural givenness of the world as an invisible construct, only made visible through stepping outside of routine and reflecting on the precariousness of health. Carel explains that a profound diagnosis “challenges the ill person to reflect on her life and search for ways of regaining meaning” (2016, p. 4). Materializing illness as a subjective piece of artwork is one such strategy, with the additional benefits of inviting others to share in an engaging collective reflection on the lacunae between illness and health. The betweenness of protection and vulnerability exemplified in this piece does not provide an answer to illness, but an open contemplation of our ethics and labours of care for one another. By layering our interpretations onto this work, an exchange of lived experiences results in the expansion of humanity and the beginning of healing.

To see more of Darian’s artwork, please visit her website: www.dariangoldinstahl.com

References

- Benthien, C. (2002). Skin. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Carel, H. (2016). Phenomenology of Illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The Visible and the invisible. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Scarry, E. (1985). The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stacey, J. (1997). Teratologies. London: Routledge.

- Stahl, D. (2019). The Prophetic Challenge of Disability Art. Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics, 39, 251-268.

- Stahl, D. (2018). Imaging and Imagining Illness: Becoming Whole in a Broken Body. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- Toombs, S. K. (1987). The Meaning of Illness: Phenomenological Approach to the patient-physician relationship. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 12, 219-240.