Challenges Encountered by Newcomers with Disabilities in Canada: An Illustration of the Ontario Disability Support Program

Défis rencontrés par les nouveaux arrivants handicapés au Canada : Une illustration du Programme ontarien de soutien aux personnes handicapées

Dora M.Y. Tam, Ph.D.

Faculty of Social Work

University of Calgary

dtam [at] ucalgary [dot] ca

Tracy Smith-Carrier, Ph.D.

School of Social Work

King’s University College at Western University

Siu Ming Kwok, Ph.D.

School of Public Policy

University of Calgary

Don Kerr, Ph.D.

Department of Sociology

King’s University College at Western University

Juyan Wang, M.Sc.

Department of Sociology

Western University

Abstract

Through a secondary data analysis of administrative data of the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) between 2003 and 2013, we aim to understand the interlocking challenges encountered by newcomers with disabilities in Canada that contribute to this population’s financial hardship. Our findings show that newcomers with disabilities on ODSP were more likely to have post-secondary education, to be older adults, to be married, common-law, and to be female who were divorced, separated, or widowed as compared to Canadian-born recipients, who were more likely to be less educated, younger, single and male. The ratio of Canadian-born to newcomer recipients on the ODSP was high between 2003 and 2013, indicating that the latter were under-represented on the program. Implications for this under-representation support future research to examine the full integration and participation of newcomers with disabilities in Canada.

Résume

Grâce à une analyse de données secondaires des données administratives du Programme ontarien de soutien aux personnes handicapées (POSPH) entre 2003 et 2013, nous visons à comprendre les défis entrelacés rencontrés par les nouveaux arrivants handicapés au Canada qui contribuent aux difficultés financières de cette population. Nos résultats montrent que les nouveaux arrivants handicapés utilisant le POSPH étaient plus susceptibles d’avoir fait des études postsecondaires, d’être ainés, d’être mariés ou en union de fait et d’être des femmes divorcées, séparées ou veuves en comparaison aux bénéficiaires nés au Canada, qui eux étaient plus susceptibles d’être moins instruits, plus jeunes, célibataires et de sexe masculin. Le ratio de bénéficiaires nés au Canada par rapport aux nouveaux arrivants utilisant le POSPH était élevé entre 2003 et 2013, ce qui indique que ces derniers étaient sous-représentés dans le programme. Les implications de cette sous-représentation appuient le besoin de nouvelles recherches visant à examiner la pleine intégration et la participation des nouveaux arrivants handicapés au Canada.

Keywords: Newcomers; Disabilities; Income Support; Ontario Disability Support Program; Canada; ODSP; Immigration

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article. This study was approved by respective university ethics review boards.Funding

No external funding on this study.Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Lindsay Savard for her dedicated research assistant work. Gratitude also goes to MaryAnn McColl, Assistant Editor of CJDS, for her patience and guidance.Introduction

Newcomers contribute to the vitality of Canadian communities by enriching our socio-cultural and linguistic diversity, contributing to economic growth and civic engagement, and participating in charitable activities and peace missions. However, integrating into a new country is not a simple process. Despite the availability of various support programs to assist with newcomer integration, and social assistance programs to lessen financial hardship, newcomers continue to experience various systemic barriers. These barriers are exacerbated for newcomers with disabilities. The term “newcomer” as used throughout this paper refers to people who were born outside of Canada and immigrated to the country under the immigration classification categories of economic, family, or refugee (Government of Canada, Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, 2018). The purpose of this paper is to understand the interlocking challenges encountered by newcomers with disabilities in Canada that contribute to this population’s financial hardship through a secondary data analysis of the administrative data imparted from the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) covering 2003 to 2013. We also compare our findings with a customized analysis on the Ontario sample from Statistics Canada’s 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability (CSD) to understand service utilization rates of ODSP. We draw upon Critical Disability Studies (Goodley, 2013; Hirschmann, 2016; Lee, 2005) to inform our discussion of the study findings.

Newcomer Policy and Statistics

Among all newcomer categories, economic immigrants are those perceived to be able to contribute to the economic growth of Canada through their education, official language proficiency, and work experience. All applicants in the economic immigrant category are required to undergo a rigorous health examination and language proficiency test in listening, reading, writing, and speaking English or French (Government of Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, n.d.). Under the family sponsorship category, Canadians or permanent residents of Canada may sponsor an eligible relative (a spouse or common-law partner, dependent child, parent, or grandparent) to Canada. The sponsor must have an income that is above the minimum necessary income or annual low-income cutoff. The sponsor must also agree, in writing, to provide the sponsored relative financial support for the length of the sponsorship undertaking agreement. The undertaking has been increased to 20 years (from 10 years) to sponsor a parent or grandparent (if the person arrived after 2014) (Government of Canada, 2013). Such financial support includes meeting their basic needs related to food, accommodation, clothing, transportation, and vision and dental care not provided by provincial health plans. These agreements are intended to ensure that the sponsored individual is inhibited from accessing programs and services reserved for permanent residents and citizens (e.g., social assistance; for more information see Smith-Carrier, 2019). However, this amendment to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulation (Government of Canada, 2013) was based on assumptions that Canada desires (able-bodied) persons who have the wherewithal to contribute to the labour market. As such, parents and grandparents of newcomers have been deemed to pose a burden to Canadian society. Yet for those who originate from collectivist cultures, such as newcomers from Middle Eastern and Asian countries, caring for one’s parents or grandparents is a highly valued and venerable practice. Given the 20-year sponsorship undertaking is such an arduous one, many newcomers are deterred from sponsoring their parents or grandparents; restricting the union of many newcomer families (Picot & Hou, 2014; Picot & Lu, 2017). The refugee category in Canada is mainly divided into two sub-categories (Government of Canada, Immigration, Refugee & Citizenship, n.d.). The first comprises government-assisted refugees, and the second includes privately sponsored refugees. Irrespective of the refugee category under which they enter Canada, individuals are expected to be responsible for their own finances once the sponsorship period ends. Due to the rigorous assessment of requirements imposed by the Canadian immigration system, considering aspects of one’s education, employability, language proficiency, and age, many individuals, specifically seniors and refuges claimants, with health conditions or disabilities are essentially screened out (El-Lahib, 2017).

In 2016, immigrants comprised roughly 22 percent of the Canadian population (Statistics Canada, 2017); a number expected to rise to 30 percent by 2036. Most - over 53 percent - of these newcomers settled in Ontario. Between 2001 and 2011, over three-quarters of Canada’s newcomer population had a mother tongue other than English or French. It is worth noting that in 2011 over 390,000 newcomers in Canada were of Arab descent, and by 2036, this figure is expected to increase to 1.3 million (Morency et al., 2017). Most newcomers from Arab countries immigrated as refugees, many of whom experienced various forms of trauma (and/or disabilities) due to regional conflicts or wars (United Nations Secretary General, 2016). Moreover, of the females who entered in 2013, 34 percent were admitted as a spouse or dependent of an economic category applicant, another 34 percent were admitted under the family category, and approximately nine percent were admitted as refugees. Although 48 percent of female newcomers in 2011 had a post-secondary degree, relative to 32 percent among the Canadian-born, these newcomers have experienced greater systemic barriers to employment in the Canadian labour force (Hudon, 2015). These statistical datapoints suggest that an intersectional lens (McCall, 2005) may be helpful in considering the challenges related to employment, health, language proficiency, financial security, and gender equity experienced by newcomers to Canada, and more specifically, those encountered by newcomers with disabilities.

In this paper, we use Critical Disability Studies (CDS) to help us understand the barriers faced by newcomers in general, and by newcomers with disabilities in particular. From a CDS perspective, an individual is not disabled by one’s respective impairment(s), but by the barriers constructed in society that impede their ability to function in the prescribed and ‘normative’ manner (Goodley, 2013; Lee, 2005). Here, intervention efforts should be aimed at removing the socio-political and/or environmental barriers that persistently marginalize people due to their impairments (Meekosha & Shuttleworth, 2009; Peters et al., 2009).

Challenges Encountered by Newcomers

Our review of the literature on newcomer integration in Canada reveals important themes, specifically: unemployment/underemployment due to unrecognized credentials attained from overseas; deteriorating health; language barriers; low-income and poverty; and negative impacts on women. Notably, these barriers exacerbate the negative impacts to newcomers with disabilities. The following section provides insight into our literature review findings.

Unemployment/Underemployment. There continues to be a significant number of newcomers who are underemployed or unemployed in Canada, despite being professionally trained and licensed in their home country. Some newcomers, entering as refugees, do so without their educational and licensing documentation in hand (i.e., degrees, diplomas, and/or certificates), preventing them from gaining entry to regulated professions in Canada (Banerjee & Phan, 2014; Wilson-Forsberg, 2015; Yssaad & Fields, 2018). Newcomers, regardless of their category of entry to Canada and background training, often find themselves working as taxi drivers, salespersons, or personal care workers — low-skilled occupations that pay minimal wages (Subedi & Rosenberg, 2017). This finding is echoed by Wilkinson et al. (2016) who found that over 50 percent of recent newcomers experience a decline in occupational and job status while living in Canada despite the fact that one in four have a university-level job in their country of origin.

Deteriorating Health. Several researchers point to the social determinants of health when discussing the health outcomes of newcomers (Pitt et al., 2015; Woodgate et al., 2017). The wellness of newcomers is negatively impacted by work instability, disabilities/impairments that hinder employment, inadequate housing, minimum wage work, irregular hours, the lack of access to professional training equivalency and accreditation, and difficulties with language acquisition. Moreover, many newcomers encounter depression, social isolation, and a loss of connection to their loved ones, leading to unhealthy eating and/or heart or blood pressure problems (Premji & Shakya, 2017; Subedi & Rosenberg, 2017). Situations are worse for refugees who originate from war-torn countries; many of whom have experienced multiple traumatic events, including familial separation, forced relocation, loss, death, injury, or even torture and rape. Due to these traumatic events, as well as adverse experiences encountered in their host country, the health of many refugees is further compromised (Betancourt et al., 2015; Woodgates et al., 2017). Despite these overwhelming stressors, newly arrived newcomers tend to use fewer mental health services than native-born Canadians (Kirmayer et al., 2011). Factors associated with the underutilization of services include varying perceptions of health needs; a lack of transportation or knowledge of available services; services without linguistic or culturally-appropriate access; the reticence to take time off work due to concerns of financial loss; and the fear of stigmatization (Chan et al., 2018; Kirmayer et al., 2011).

Language Barriers. Language proficiency plays a significant role in determining whether newcomers can obtain gainful employment and experience positive social integration. However, research has found that language barriers affect women more acutely than men, as Wilson-Forsberg (2015) found that home care responsibilities do not generally allow women to gain the same degree of experience practicing English as they would if they were in paid employment. As such, adequate support programs for newcomers are necessary to remove the language barriers than impede social integration. Despite these challenges, newcomers who come to Canada as refugees are expected to be “self-sufficient” after only a year of government sponsor support or the private sponsor must commit to continuing support. As previously mentioned, refugees migrating to Canada because of war or political confrontation in their home country may acquire post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or other chronic health conditions (United Nations Secretary General, 2016). Newcomers who have experienced war-related traumas and/or political torture may thus require support beyond the one-year sponsorship agreement undertaking.

Income Insecurity. Findings from Picot and Lu (2017) show that in the year 2012, newcomers, relative to Canadian-born individuals, were 3.3 times more likely to live in chronic low-income, defined as “having a family income under a low-income cut-off for five consecutive years or more” (p. 5). In 2012, 30 percent of newcomer older adults (aged 65 or above) experienced chronic low-income compared to only two percent of the Canadian-born older adult population. Moreover, newcomers who were unattached or lone parents were among those reporting higher-than-average chronic low-income. Low income is highly correlated to unemployment/ underemployment status, language barriers, and unrecognized credentials. The complexity of income insecurity for newcomers is clearly understood through a critical lens that considers the implications of policies and institutional barriers on newcomer families, which perpetuate and maintain discriminatory practices that prevent newcomers from moving outside low-income thresholds (Nickel et al., 2018; Pitt et al., 2015).

Negative Impacts on Immigrant Women. Unemployment/underemployment, deteriorating health, language barriers, and income insecurity are generally experienced by many newcomers, although experiences of social integration impact newcomer women differently than men. A study by Hudon (2015) showed that newcomer women reported feelings of incompetence; inferiority or dependence (as many of them were unable to afford childcare); strained to complete unremitting domestic duties; and struggled to juggle low-paid jobs and care responsibilities in the home. Many newcomer women disclosed that they could not afford healthy food and necessary medications, and were unable to qualify for extended health benefits, including access to paid sick days (Premji & Shakya, 2017). Another study conducted by Kaida (2015) found that 60 percent of European-born newcomer women exited poverty after four years in Canada, while only 22 percent of Arab women and 28 percent of West Asian women were able to do so. Race and ethnicity clearly matter when considering the unemployment/ underemployment trajectories of newcomer women.

Limited Understanding about Newcomers with Disabilities. Although there exist general statistics about disability in Canada, research on newcomers with disabilities is relatively thin. In 2017, one in five Canadians (22 percent or about 6.2 million people) aged 15 years and over had one or more disabilities (Morris et al., 2018). Among all individuals with disabilities, older adults were almost twice as likely to have impairment(s) as working-age adults aged 25 to 64 years. Moreover, people with disabilities were less likely to be employed than those without. The employment rate among people with disabilities in 2016 was 59.4 percent compared to 80.1 percent for those without impairment(s). Furthermore, women with mild impairments experienced income levels roughly three-quarters that of men with such impairments. People with disabilities (between the ages of 15 to 64 years) who were lone parents or lived alone had the highest likelihood of living in poverty (Morris et al., 2018). The nexus of intersections related to gender, age, and marital status more adversely affect women with disabilities. Yet little is known about newcomers with disabilities. This study therefore explores the contributing factors leading to the increased vulnerability of this population. Applying a CDS lens (Goodley, 2013), we recognize the (under)privileging of certain identity markers to highlight the intertwined layers of domination and subordination that result in the inequities experienced by newcomers with disabilities.

Purpose and Research Questions

Through a secondary data analysis of administrative data of the ODSP between 2003 and 2013, we aim to understand the interlocking challenges encountered by newcomers with disabilities in Canada that contribute to this population’s financial hardship. Our specific research questions include: i) what were the ratios of ODSP utilization between newcomers and the Canadian-born when compared to the ratio of persons with disabilities on the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability in Ontario; and ii) what are the variables (e. g., gender, education, family structure, marital status, and age) that differentiate financial vulnerability among participants of ODSP when compared to individuals born in Canada and those born outside the country.

Research Methodology

Design and Data We conducted secondary data analyses of administrative data from the ODSP collected by the Ontario Ministry of Community and Social Services.

Sample. We included all primary applicants who received ODSP between January 2003 and December 2013. The ODSP’s mandate is to provide financial assistance and employment support to enable individuals with disabilities and their families to live as independently as possible in their communities. An ODSP applicant must meet the definition of a person with a disability as defined by the ODSP Act, 1998 (ODSP Act) or be a member of a “prescribed class” (Government of Ontario, n.d.). Unless the requirement is deferred or waived, spouses and dependent adults without a disability on ODSP must agree to participate in employment and employment assistance activities as a condition of ongoing eligibility (Government of Ontario, n.d.).

Analysis. Our analysis focused on comparing group differences between primary applicants of ODSP (newcomers [i.e., born abroad] versus Canadian-born) between January 2003 and December 2013. The demographic characteristics of interest for our comparison, which intersect with having an impairment(s), include gender, education, family structure (e.g., living with children or not), marital status, and age. Moreover, we examined the findings from the ODSP administrative data. We also compared ratios of Canadian-born and newcomer in the general population of Ontario in 2001, 2006, 2016, and 2011 as well as comparing the data from a customized analysis on the Ontario sample from the Canadian Survey on Disability (CSD) (Statistics Canada, 2020), in order to better understand how the intersected relationship of disability with immigrant status and the five demographic variables identified.

Findings

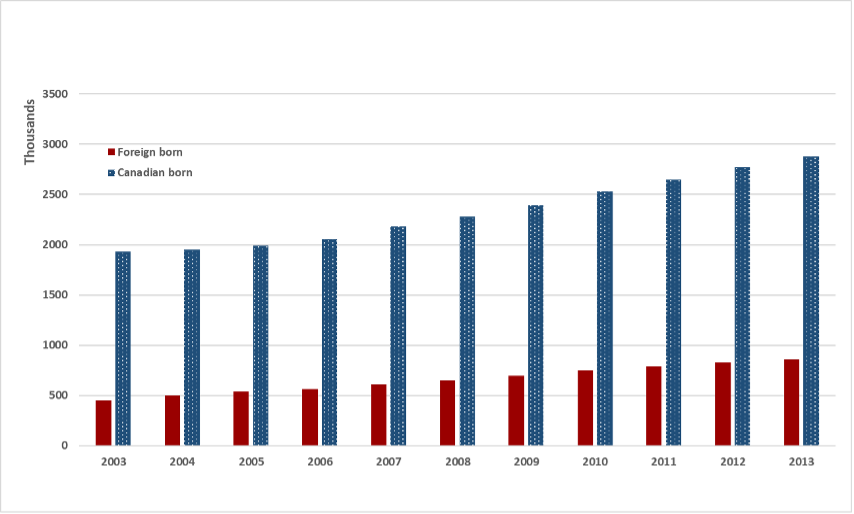

ODSP Utilization. The first question we examined was the ratio of ODSP utilization between newcomers and the Canadian-born. We then compared the utilization rates between the two groups with the percentages of immigrants in the general population in Ontario and provincial statistics from the CSD (Statistics Canada, 2020). Figure 1 provides the annual caseload numbers of all primary applicants on ODSP by place of birth (i.e., newcomers and Canadian-born) between January 2003 and December 2013. As shown on Figure 1, yearly ODSP caseloads increased gradually among both the Canadian-born and newcomer groups from 2003 to 2013.

One question that arises when considering annual ODSP caseloads is what the utilization rate is compared to the general population of Ontarians identified with disabilities in the CDS (Statistics Canada, 2020). To best answer this question, Census data would likely be the preferred resource; however, questions related to immigration status were abandoned when the mandatory long-form was replaced by the 2011 Census. As a result, the closest comparable data source is the National Household Survey. Therefore, using both Census data (Statistics Canada, 2002, 2007, 2017) and data from the National Household Survey (Statistics Canada, 2013), we identified the ratios between Ontarians who identified themselves as Canadian-born and foreign-born.

Figure 1

Annual Caseloads of ODSP Primary Applicants by Birthplace between January 2003 and December 2013

We examine data from the customized analysis on the Ontario sample of CSD (Statistics Canada, 2020), which provide the best portrait of Ontarians with disabilities identified as Canadian-born or foreign born. Table 1 summarizes the respective ratios between the Canadian-born and newcomers on ODSP in the general Ontario population, and in the subset of data for Ontarians on the CSD. As demonstrated in Table 1, the ratio of Canadians to newcomers on ODSP is steadily decreasing over the 11-year period from 4.26 in 2003 to 3.35 in 2013. However, a further comparison on the ratios between Canadian-born and newcomers on ODSP (i.e., ranged between 3.35 and 4.26) are greater than the ratios found in the general population of Ontario (i.e., ranged between 2.39 and 2.70), and for Ontarians on the CSD (i.e., 2.46). In other words, there is a greater proportion of Canadian-born individuals with disabilities who utilize ODSP, whereas the ODSP utilization rate among the newcomers with disabilities is relatively small. The factors hindering newcomers with disabilities’ use of social assistance programs is beyond the scope of this study; however, we did examine the demographic characteristics of this population that could impede their financial independence, potentially impacting their access of social assistance programs such as the ODSP.

Table 2

Ratios between Canadian-born and Newcomer Primary Applicants on ODSP (January 2003 and December 2013), ratios between Canadian-born and Newcomers in the Census (2001, 2006 and 2016) and National Household Survey (NHS, 2011), and ratio between Canadian-born and Newcomer Ontarians in the CSD (Statistics Canada, 2020)| Year | Canadian Born on ODSP | Newcomers on ODSP | Ratio on ODSP | Canadian Born Ontarians on Census/ NHS Data | New-comer Ontarians on Census/ NHS Data | Ratio on Census/ NHS Data | Canadian Born Ontarians on CSD | New-comer Ontarians on CSD | Ratio on CSD |

| 2001 | 8,164.86 | 3,030.08 | 2.70 | ||||||

| 2003 | 1932.84 | 454.08 | 4.26 | ||||||

| 2004 | 1952.66 | 500.57 | 3.90 | ||||||

| 2005 | 1988.57 | 535.03 | 3.72 | ||||||

| 2006 | 2058.23 | 563.87 | 3.65 | 8,512.02 | 3,398.73 | 2.50 | |||

| 2007 | 2177.38 | 613.15 | 3.55 | ||||||

| 2008 | 2279.84 | 652.94 | 3.49 | ||||||

| 2009 | 2393.77 | 698.73 | 3.43 | ||||||

| 2020 | 2527.70 | 746.63 | 3.39 | ||||||

| 2011 | 2648.23 | 785.76 | 3.37 | 8906.00 | 3,611.37 | 2.47 | |||

| 2012 | 2770.74 | 825.17 | 3.36 | ||||||

| 2013 | 2877.73 | 857.95 | 3.35 | ||||||

| 2016 | 9,188.82 | 3,852.15 | 2.39 | ||||||

| 2017 | 1,849.39 | 750.89 | 2.46 |

Group Differences. Our primary research question was to understand if any group differences exist between the number of newcomers on ODSP as compared to Canadian-born. The demographic variables examined in this study included gender, education, family structure, marital status, and age. A difference of 10 percentage points or more was deemed to be substantial (i.e., newcomers vs. Canadian-born, and female vs. male). Table 2 presents demographic statistics on all ODSP primary applicants from January 2003 to December 2013; whereas Table 3 compares newcomers to those born in Canada and any differences by gender. Unique demographic differences between newcomer and Canadian-born ODSP primary applicants are also shown. From these data we observe that Canadian-born primary applicants were 1.24 times more likely to have less than a high school education than newcomers (53.3 percent versus 43.1 percent). In addition, Canadian-born applicants were 1.71 times more likely to be single than their newcomer counterparts (56.5 percent versus 32.9 percent). It is also worth noting that Canadian-born adults were 2.3 times more likely to be young (between the ages of 18 and 29 years old) compared to newcomers on ODSP (16.8 percent versus 7.2 percent).

What are the unique demographic characteristics of newcomer primary applicants on ODSP? Some characteristics include the following: i) newcomers were 1.75 times more likely to have a post-secondary education as compared to the Canadian-born (25.3 percent versus 14.5 percent); ii) newcomers were 1.79 times more likely to be married or in common-law relationships (22.9 percent versus 12.8 percent); iii) newcomers were 1.44 more likely to be divorced, separated, or widowed than their Canadian-born counterparts (44.2 percent versus 30.7 percent); and iv) there were 2.7 times more newcomers aged 60 or above on ODSP as compared to Canadian-born older adults (29.4 percent versus 10.8 percent). We subsequently examined within-group differences between female and male newcomers on ODSP (primary applicants only).

Table 3

Frequency Distributions of All Primary Applicants on ODSP between Jan 2003 to Dec 2013 by Place of Birth| ODSP Primary Applicants (%) | ||||||

| Newcomers | Canadian-Born | |||||

| Total | 22.0 | 78.0 | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 43.1 | 53.3 | ||||

| High School/Apprenticeship/Trades Certificate/ Diploma | 28.0 | 27.1 | ||||

| Post-secondary | 25.3 | 14.5 | ||||

| Living Arrangements | ||||||

| Couples or singles without children | 79.7 | 87.6 | ||||

| Couples or singles with children | 20.4 | 12.4 | ||||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | 32.9 | 56.5 | ||||

| Married or common-law | 22.9 | 12.8 | ||||

| Divorced, separated or widowed | 44.2 | 30.7 | ||||

| Age Group | ||||||

| 18 – 29* | 7.2 | 16.8 | ||||

| 30 - 59 | 63.3 | 72.4 | ||||

| 60+ | 29.4 | 10.8 | ||||

Notes: * May involve parents between the ages of 15 to 17 in receipt of ODSP

In addition to differences found in relation to place of birth, notable differences were identified between males and females on specific demographic variables. First, the Canadian-born male who had less than a high school education were 1.25 times more likely to be male than their female counterparts. Second, Canadian-born males on ODSP were 1.28 times more likely to be couples or single without children than Canadian-born females. However, for couples or singles with children, Canadian-born females on ODSP were 2.16 times more likely than Canadian-born males. With regards to marital status, Canadian-born males were 1.54 times more likely to be single, whereas Canadian-born females on ODSP were 1.70 times more likely to be divorced, separated or widowed. Moreover, Canadian-born males were 1.40 times more likely to be younger (aged 18 to 29 years old) than was true for Canadian-born females. This begs the question, are there gender difference among newcomers on the ODSP?

Table 4

Percent of Canadian-born and Newcomer ODSP applicants by Gender (2003-2013)| ODSP All Primary Applicants (%) | |||||||

| Newcomers | Canadian-Born | ||||||

| F | M | F | M | ||||

| TOTAL | 50.2 | 49.8 | 46.9 | 53.1 | |||

| Education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 54.1 | 45.9 | 44.5 | 55.5 | |||

| High School/Apprenticeship/Trades Certificate/Diploma | 47.3 | 52.7 | 47.6 | 52.5 | |||

| Post-secondary | 48.6 | 51.4 | 45.9 | 54.1 | |||

| Living Arrangements | |||||||

| Couples or singles without children | 48.1 | 51.9 | 43.8 | 56.2 | |||

| Couples or singles with children | 58.4 | 41.6 | 68.4 | 31.7 | |||

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Single | 40.8 | 59.2 | 39.4 | 60.6 | |||

| Married or common-law | 28.6 | 71.4 | 41.2 | 58.8 | |||

| Divorced, separated or widowed | 68.5 | 31.6 | 62.9 | 37.1 | |||

| Age Group | |||||||

| 18 – 29* | 38.6 | 61.4 | 41.7 | 58.3 | |||

| 30 - 59 | 50.3 | 49.7 | 47.6 | 52.4 | |||

| 60+ | 53.0 | 47.0 | 50.3 | 49.7 | |||

Notes: *May involve parents between the ages of 15 to 17 in receipt of ODSP

On the variables of education and age, even though there was 1.75 times more of newcomers with post-secondary education as compared to their Canadian-born counterparts, and 2.70 times more of the newcomers aged 60 and above than the Canadian-born, there was no gendered difference for either of these variables. In other words, the intersection of disability, educational overqualification, and age impacts newcomers more than their Canadian-born counterparts regardless of gender. Differences, however, were found related to gender by living arrangements, marital status, and age among newcomers.

In relation to living arrangements, female newcomer parents, no matter whether they identified as in a couple or single, were 1.4 times more to live on ODSP than was the case for male newcomers. Considering marital status, male newcomers on ODSP were 1.45 times more to be single than female newcomers, whereas male newcomers were 2.50 times more to be married or common-law than was true for female newcomers. However, among those divorced, separated or widowed, female newcomers were 2.17 times more to rely on ODSP than male newcomers. With regards to age group, young male newcomers ages 18 to 29 were 1.59 times more to be on ODSP than was true for female newcomers; however, no differences were found in relation to the other age groups of male and female newcomers. Clearly, immigration status and gender must be taken into account when examining the intersection of disability with other demographic variables such as education, family structure, marital status, and age.

Discussion and Implications

Congruent with an intersectional lens (McCall, 2005), the ability of a person with disabilities to achieve improved health and well-being largely depends on different contributing factors. This study provides valuable findings that attest to how the intersections of disability, gender, education, the presence of children, the absence of a marital or common-law partner, and age intertwine, leading to varying levels of ODSP participation among newcomers and the Canadian-born.

Our findings demonstrate that: i) the ratio of Canadian-born ODSP participants to newcomers was between 3.35 and 4.26 higher between 2003 and 2013, whereas the ratios of Canadian-born Ontarians to newcomer Ontarians in the general population (i.e., ranged between 2.39 and 2.70), and the ratio between Canadian-born and newcomers on 2017 CSD (i.e., 2.46) were both lower. Newcomers were thus under-represented among ODSP recipients during the period of 2003 and 2013. Canadian-born ODSP recipients, relative to newcomer recipients, were less educated, and more likely to be single and younger. Newcomer ODSP recipients were more likely to have post-secondary education, to be older adults, and to be married, common-law, divorced, separated, or widowed as compared to Canadian-born recipients. These findings have important implications for practice and service delivery to newcomers.

The demographic statistics derived from the ODSP administrative dataset provide evidence that challenges the myth that newcomers constitute a burden to our social assistance system. Indeed, fewer newcomers with disabilities in Ontario utilized ODSP even though they represent a greater proportion of those on the CSD (Statistics Canada, 2020).

The fact that there are a greater number of divorced, separated or widowed women on ODSP than men suggests that gender-neutral policy solutions may not be helpful. Specifically, lone parents may face added life stressors arising from divorce, separation and/or widowhood that can exacerbate the challenging effects of their impairments. These adverse effects can have profound health impacts on the psycho-social and intellectual development of children of newcomer parents with disabilities.

Research documents the persistence of chronic low-income among the newcomer population in Canada, specifically among women refugees (e.g., Picot & Lu, 2017; Picot et al., 2019), and the detrimental relationship between food insecurity and poor academic achievement among adolescent newcomers (Roustit et al., 2010). Government efforts are required to ensure that supports keep pace with the rising cost of living, specifically for female newcomer parents with disabilities who also care for dependent children and may not have time or easy access to language or employment skills training, limiting their prospects for any supplementary waged income.

Research has also shown that, relative to children born in Canada, children of newcomers are more vulnerable to mental health-related issues and learning disabilities (Busby & Corak, 2014; Chen et al., 2015). Clear negative impacts have been demonstrated in studies on children and youth mental health in families on social assistance (e.g., Comeau et al., 2020). Questions linger as to what can be done to assist newcomers, who may or may not have impairments, to improve their reception in the Canadian labour market and enhance their health and well-being.

Scholarly research has demonstrated that older adults are almost twice as likely to have a disability than working-age adults ages 25 to 64 years (Morris et al., 2018). In our study, the ratio of disability among newcomer older adults on ODSP was even higher: the percentage of persons aged 60 plus was close to three times greater for newcomers than was true for Canadian-born ODSP recipients. Despite their higher education level, the combination of newcomers’ immigration status, disability and residency requirements attached to Canadian pension programs further push newcomer older adults into greater income insecurity, if not chronic low-income (Picot & Lu, 2017). Under Immigration and Refugee Protection regulations, an individual who wishes to sponsor her/his parents or grandparents must sign for and undertake “provid[ing] food, clothing, shelter, fuel, utilities, household supplies, personal requirement and other groups and services, including dental care, eye care, and other health needs not provided by public health care” (Government of Canada, Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship, n.d.). The duration of such an undertaking for parents and grandparents has increased from 10 years to 20 years after 2014, which is also the end year of our data analysis period. What then will the implications be for newcomer parents and grandparents who arrived after 2014? Will newcomer older adults with disabilities experience further marginalization under this new regulation? More research is needed to better understand the complexity of disability, gender, age, and well-being among this population.

Current literature suggests the compounding effects of being a newcomer and disabled increase the likelihood that this group will experience poorer health and well-being (Lu & Ng, 2019). Newcomers with disabilities (and their families) are more susceptible to poverty, and the poor quality of life associated with it (Frank & Hou, 2017). These families encounter greater difficulties in meeting their basic needs, including shelter, clothing, food, and transportation, not to mention the funds necessary to secure extra-curricular supplies and/or activities for their children.

In coming to Canada, newcomers (regardless of their level of education and marital status) typically leave behind much of their extended family and social networks, resulting in many reporting social isolation, which can also be compounded by language or cultural barriers (Subedi & Rosenberg, 2017; Woodgates et al., 2017). It is imperative then that direct service providers develop culturally sensitive protocols to work effectively with newcomers. Rather than individualistic (and often fragmented) service provision, settlement services for newcomers with disabilities should adopt a holistic, family-focused approach that aims to address the needs of all newcomer family members (Ashbourne & Baobaid, 2019). Further research is needed to better understand the processes of integration and participation of newcomers with disabilities in Canada.

Limitations and Further Considerations

There are two apparent limitations of this study. First, no information was available on where the post-secondary education attained by newcomer ODSP applicants was achieved, either in their country of origin or in Canada. In other words, it is unclear whether the job insecurity experienced by newcomers with disabilities was primarily a result of the lack of recognition of their professional or educational qualifications, their lack of Canadian work experience, the presence of substantial impairments, difficulties with earnings exemptions (income clawbacks on paid work) on ODSP, or some combination of the above. Greater in-depth analysis of these factors and their interactions could prove useful in broadening this discussion. Second, this study presents the findings of a descriptive analysis only. Moving forward, an inferential study that controls for the variables of gender, level of education, family structure, age, and years of stay in Canada might allow for a more thorough comparison of newcomers and Canadian-born with disabilities.

References

- Ashbourne, L. M., & Baobaid, M. (2019). A collectivist perspective for addressing family violence in minority newcomer communities in North America: Culturally integrative family safety responses. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 11, 315-329. doi:10.1111/jftr.12332

- Banerjee, R., & Phan, M. (2014). Licensing requirements and occupational mobility among highly skilled new immigrants in Canada. Industrial Realtions, 69(2), 290-315. doi.org/10.7202/1025030ar

- Betancourt, T. S., Abdi, S., Ito, B. S., Lilienthal, G. M., Agalab, N., & Ellis, H. (2015). We left one war and came to another: Resource loss, acculturative stress, and caregiver-child relationships in Somali refugee families. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(1), 114–125. doi:10.1037/a0037538

- Busby, C., & Corak, M. (2014). Don’t forget the kids: How immigration policy can help immigrants’ children. C.D. Howe Institute.

- Chan, M., Johnston, C., & Bever, A. (2018). Exploring health service underutilization: A process evaluation of the newcomer women’s health clinic. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health, 20, 920 – 925. doi: 10.1007/s10903-017-9616-2

- Chen, K., Osberg, L., & Phipps, S. (2015). Inter-generational effects of disability benefits: Evidence from Canadian social assistance programs. Journal of Population Economics, 28, 873 – 910. doi: 10.1007/s00148-015-0557-9

- Comeau, J., Duncan, L., Georgiades, K., Wang, L., & Boyle, M. H. (2020). Social assistance and trajectories of child mental health problems in Canada: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111, 585-593. doi.org/10.17269/s41997-020-00299-1

- El-Lahib, Y. (2017). The well-being of immigrants with disabilities. In M. C. Yan & A. Uzo (Eds.), Working with immigrants and refugees: Issues, theories, and approaches for social work and human service practice (pp. 288 – 308). Oxford University Press.

- Frank, K., & Hou, F. (2017). Over-education and life satisfaction among immigrant and non-immigrant workers in Canada. Catalogue No.: 11F0019M-393. Statistics Canada.

- Goodley, D. (2013). Dis/entangling critical disability studies. Disability & Society, 28(5), 631-644.

- Government of Canada, Immigration, Refugee, and Citizenship. (n.d.). Family Sponsorship. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/application/application-forms-guides/guide-5772-application-sponsor-parents-grandparents.html

- Government of Canada, Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship. (2018). Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration. Cat. No.: Ci1E-PDF. The Author.

- Government of Canada. (2013). New qualifying criteria for permanent residency sponsorship. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/archives/backgrounders-2013/action-plan-faster-family-reunification-phase.html

- Government of Ontario. (n.d.). Ontario Disability Support Program Directives. Retrieved from https://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/mcss/programs/social/directives/odsp/is/2_5_ODSP_ISDirectives.aspx

- Hirschmann, N. J. (2016). Disabling barriers, enabling freedom. In B. Arneil & N. J. Hirschmann (Eds.), Disability and political theory (pp. 99-122). Cambridge University Press.

- Hudon, T. (2015). Immigrant women. Catalogue No.: 89-503-X. Statistics Canada.

- Kaida, L. (2015). Ethnic variations in immigrant poverty exit and female employment: The missing link. Demography, 52(2), 485-511. doi:10.1007/s13524-015-0371-8

- Kirmayer, L. J., Narasiah, L., Munoz, M., Rashid, M., Tyder, A. G., Guzder, J., Hassan, G., Rousseau, C., & Pottie, K. (2011). Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. CMAJ, 183(12), E959-E967. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090292

- Lee, T. M. L. (2005). Multicultural citizenship: The case of the disabled. In D. Pothier, and R. Devlin (Eds.), Critical disability theory: Essays in philosophy, politics, policy & law (pp.87-105). UBC Press.

- Lu, C., & Ng, E. (2019). Health immigrant effect by immigrant category in Canada. Catalogue No.: 82-003-X. Statistics Canada.

- McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs, 30(3), 1771-1800. doi: https//ww.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/426800

- Meekosha, H., & Shuttleworth. (2009). What’s so ‘critical’ about critical disability studies? Australian Journal of Human Rights, 15(1), 47-76.

- Morency, J. D., Malenfant, É. C. & Maclsaac, S. (2017). Immigration and diversity: Population projections for Canada and its regions, 2011 to 2036. Catalogue No.: 91-551-X. The Author.

- Morris, S., Fawcett, G., Brisebois, L., & Hughes, J. (2018). A demographics, employment and income profiles of Canadians with disabilities aged 15 years and over, 2017. Cat. No.: 89-654-X2018002. Statistics Canada.

- Nickel, N. C., Lee, J. B., Chateau, J., & Paillé, M. (2018). Income inequality, structural racism, and Canada’s low performance in health equity. Healthcare Management Forum, 31(6), 245-251. doi: 10.1177/0840470418791868

- Norcliffe, G., & Bates, J. (2018). Neoliberal governance and resource peripheries: The case of Ontario’s mid-north during the “common sense revolution.” Studies in Political Economy, 99(3), 331-354. https://doi.org/10.1080/07078552.2018.1536372

- Peters, S., Gabel, S., & Symeonidou, S. (2009). Resistance, transformation and the politics of hope: Imagining a way forward for the disabled people’s movement. Disability & Society, 24(5), 543-556.

- Picot, G. & Hou, F. (2014). Immigration, low income and income inequality in Canada: What’s new in the 2000s? Catalogue No.: 11F0019M-No. 364. Statistics Canada.

- Picot, G., & Lu, Y. (2017). Chronic low income among immigrants in Canada and its communities. Catalogue. No.: 11F00119M-No.397. Statistics Canada.

- Picot, G., Zhang, Y., & Hou, F. (2019). Labour market outcomes among refugees to Canada. Catalogue No.: 11F0019M-419. Statistics Canada.

- Pitt, R. S., Sherman, J., & Macdonald, M. E. (2015). Low-income working immigrant families in Quebec: Exploring their challenges to well-being. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 106(8). doi:10.17269/CJPH.106.5028

- Premji, S., & Shakya, Y. (2017). Pathways between under/unemployment and health among racialized immigrant women in Toronto. Ethnicity & Health, 22(1), 17-35. doi:10.1080/13557858.2016.1180347

- Roustit, C., Hamelin, A-M., Grillo, F., Martin, J., & Chauvin, P. (2010). Food insecurity: Could school food supplementation help break cycles of intergenerational transmission of social inequalities? Pediatrics, 126(6), 1174-1181. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3574.

- Smith-Carrier, T. (2019). Universality and immigration: Differential access to social programs and societal inclusion. In D. Béland, P. Marchildon, & M. J. Prince (Eds.), Universality and Social Policy in Canada (pp. 155-178). University of Toronto Press.

- Statistics Canada. (2002). 2001 Community Profiles. Released June 27, 2002. Last modified: 2005-11-30. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 93F0053XIE. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/english/Profil01/CP01/Index.cfm?Lang=E

- Statistics Canada. (2007). 2006 Community Profiles of Ontario. Catalogue no. 92-591-XWE. Ottawa. Released March 13, 2007. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/prof/92-591/index.cfm?Lang=E.

- Statistics Canada. (2013). National Household Survey (NHS) Profile 2011. Catalogue no. 99-004-XWE. Ottawa. Released September 11, 2013. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E.

- Statistics Canada. (2017). Census Profile 2016. Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Released November 29, 2017. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E.

- Statistics Canada. (2020). Customized analysis of the Ontario sample on the Canadian Survey on Disability, 2017. The Author.

- Subedi, R. P., & Rosenberg, M. W. (2017). "I am from nowhere": Identity and self-perceived health status of skilled immigrants employed in low-skilled service sector jobs. International Journal of Migration, Health, and Social Care, 13(2), 253 - 264.

- United Nations Secretary General. (2016) In Safety and Dignity: Addressing Large Movements of Refugees and Migrants. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/70/59&=E%20

- Wilson-Forsberg, S. (2015). "We don't integrate; we adapt:" Latin American immigrants interpret their Canadian employment experiences in southwestern Ontario. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 16(3), 469. doi:10.1007/s12134-014-0349-1

- Wilkinson, L., Bhattacharyya, P., Bucklaschuk, J., Shen, J., Chowdhury, I. A., & Edkins, T. (2016). Understanding job status decline among newcomers to Canada. Canadian Ethnic Studies Journal, 48(3), 5-26.

- Woodgate, R. L., Busolo, D. S., Crockett, M., Dean, R. A., Amaladas, M. R., & Plourde, P. J. (2017). A qualitative study on African immigrant and refugee families’ experiences of accessing primary health care services in Manitoba, Canada: It’s not easy. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(5). doi:10.1186/s12939-016-0510-x

- Yssaad, L., & Fields, A. (2018). The Canadian immigrant labour market: recent trends from 2006 to 2017. Catalogue No.: 71-606-X. Statistics Canada.