“Cripping Sex Education”: A Panel Discussion for Prospective Educators

Chelsea Temple Jones

Department of Child and Youth Studies

Brock University

cjones [at] brocku [dot] ca

Emily Murphy

Department of Child and Youth Studies

Brock University

emurphy2 [at] brocku [dot] ca

Sage Lovell

Deaf Spectrum

info [at] deafspectrum [dot] com

Nadia Abdel-Halim

Unit for Social and Community Psychiatry, East London NHS Foundation

nadia [dot] halim [at] nhs [dot] net

Ricky Varghese

Faculty of Community Services, Toronto Metropolitan University and Toronto Institute of Psychoanalysis

ricky [dot] r [dot] varghese [at] gmail [dot] com

Fran Odette

Assaulted Women and Children Counsellor/Advocate Program, George Brown College

fran [at] cnwondernorth [dot] com

Andrew Gurza

Disability After Dark

andrew [at] andrewgurza [dot] com

Introduction

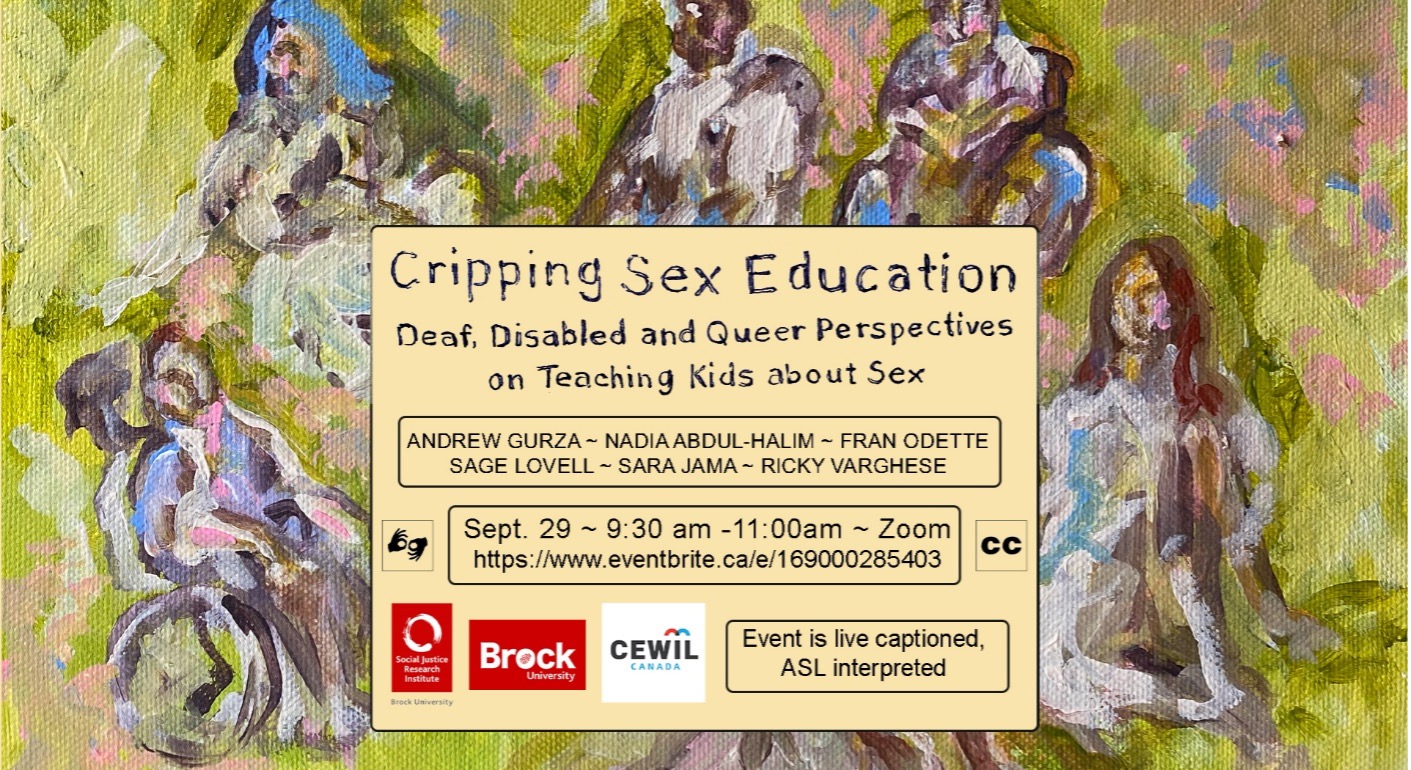

In 2021 a group of 76 third-year undergraduate students, many of whom are prospective educators, designed six distinctly different accessible, open-access digital tools to “crip sex education” in partnership with disabled, Deaf, and queer community-based activists. This experiential education project, called “Cripping Sex Education: Developing Digital Tools for Disabled, Deaf, and Queer Kids,” began with a public panel discussion. This online panel responded to the 2020 call to “crip sex education,” articulated in a special issue of Sex Education, whose editors highlight the erasure of disabled children’s experiences in mainstream curricula and forecast a future where scholars and activists might “work to create more inclusive and holistic sex education curricula as well as more inclusive educational environments for all students” (Campbell, Löfgren-Mårtenson & Martino, 2020, p. 365). Prior to the students forming their community partnerships as part of the larger “Cripping Sex Education” project, the panel gathered five activists—Sage Lovell, Andrew Gurza, Ricky Varghese, Nadia Abdel-Halim and Fran Odette—to discuss their experiences of sex education within their respective communities and to make recommendations for students’ forthcoming digital tool creation. The September 29 panel, held via Zoom, drew a 98-person audience, and marked a launching point for wider classroom conversations about disabled, Deaf and queer activists’ push-back against their communities’ disavowal in mainstream curricula. This conversation later translated into student projects: an American Sign Language Glossary (ASL) glossary for sex-related slang, a website dedicated to consent, and a guide for safely planning dates online, among other initiatives that considered crip sexual citizenship.

Below is an abbreviated transcript of the 90-minute panel, edited and sectioned for length. Preceding this transcript are speakers’ descriptions of themselves in the order which they appeared, extracted from their opening greetings and wider introductions, as well as a land acknowledgement.

Panellists

Chelsea Temple Jones (moderator): My pronouns are she/her. I’m a white, middle-aged assistant professor in Brock University’s Department of Child and Youth Studies and speaking to you as a white settler living in Toronto. I’m also the teacher for a class called “CHYS 3P44: Gender, Sexuality, Childhood and Youth” which is hosting this panel. I have shoulder length brownish-grey hair and I am wearing glasses.

Sage Lovell: My name, Sage, is a sign just off the chin. In Deaf culture we refer to each other with sign names, which function much like a standardized name in English, though here you would pick something that is representational of a feature you have—whether that be a strong physical feature or a personality trait. My pronouns are they/them and I identify as non-binary. I’ve got curly brown hair with some green streaks and right now I’m wearing a black shirt with a baby blue cardigan and behind me you can see a beige wall. I’m from Milton, which is the traditional land of the Mississauga of the Credit First Nations, Huron-Wendat and Haudenosaunee people.

Andrew Gurza: I have short brown hair, I’m a white, cis-male and I am a person who uses a wheelchair and behind me is my Professor X poster. I use the pronouns they and he to describe myself and my disability identifier is disabled.

Ricky Varghese: I would describe myself as a dark-skinned, South Asian, cis-gendered man. I identify as queer, and I go by he/him pronouns. I am a social worker and a psychotherapist, in private practice. I’m also doing my post-doctoral fellowship right now, at X University in the School of Disability Studies.

Nadia Abdel-Halim: My pronouns are she/her. I am currently wearing big white and silver earrings, and I'm sitting against a white background, beside a window, and there is a plant that is hanging in the background. I’m joining this call from London, England. And while this may be one of the few places that the English had any business calling Great Britain during the length of the imperial campaign, it's important to acknowledge that I'm working within systems that were moulded throughout the displacement of peoples and the devastation of rich tapestries of culture.

Fran Odette: I'm someone who has done disability activism and education for about 25 + years and much of my work has focused on education, training, and consulting around programming, as it relates to creating an inclusive and accessible environment for youth and adults living with disabilities. I am someone who lives with a disability. I am also someone who is a white settler. I identify as a feminist and I'm also part of the LGBTQ+ community. And now, I'm also considered an elder – kind of an interesting part of my own lived experience. I am light-skinned. I am sitting in my wheelchair. I have glasses with little triangles on the side that are the colors of orange, blue, and red. I have short hair that is a salt-and-pepper colour. I'm wearing a patterned, black-and-gray top with sort of sparkly things on the collar. I am sitting in my office and behind me I have bookshelves, and there is also a picture of a goddess that I love, and she follows me wherever I get to be.

Land Acknowledgement:

Chelsea Temple Jones: Brock University is located on the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe peoples, and this territory is covered by the Upper Canada Treaties and is within the land protected by the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Agreement. This Agreement explains the ways each Nation who lives here is meant to share this territory peacefully, by using a spoon (rather than a knife) to share in what the earth provides. We recognize that this Agreement is still in effect today but has not been properly upheld by the state. Today our focus is centered on young disabled, deaf, and queer people’s experiences with sexual education—or lack of it. This focus does not preclude the ongoing, state-sanctioned harm toward Indigenous children who might identify two-spirited, or be categorized as, disabled, deaf, queer, or otherwise. We also remember that Indigenous children’s access to something like sex education is complicated by ongoing colonial violence as Indigenous children are routinely taken away from their families and subject to the colonial tools of sexism, transphobia, and homophobia among others. We recognize, as well, the dynamic and vital role of children’s activism as they advance the calls for gender identity reform and for clean driving water in their communities, and as they advocate for their missing mothers, sisters, and other community members who lives have been lost to colonial, and often sexual, violence.

Our relationships to the land are different depending on where we are and our access to Internet; a virtual meeting like this unsettles our positions. For this reason, Fran Odette has offered to share a crip land acknowledgement video. This signed land acknowledgement is hosted on the Making Accessible Media website. Thank you to Fran Odette, Margaret Alexander, Melanie Marston, Marsha Ireland, and Anne Zbitnew for producing that land acknowledgement and offering to share it with us today.

"Cripping Sex Education" Panel Discussion:

Sage Lovell: I started identifying as queer at 11 or 12 years old and it was at this age that I also started to date and express curiosity in sexual experiences. At this time, though, there was little to no discussion of queer sexual experiences in formal sex education. I was also at a mainstream school that consisted primarily of hearing students, with only a small number of Deaf students. Sometimes the hearing students would look as my ASL interpreter and make comments like “wow, look how visual that is” and the sort—but this impacted my learning experience, because when ASL interpretation becomes sensationalized then it becomes uncomfortable. And so, I learned a little bit at a time and very slowly.

It wasn’t until I reached university that I encountered truly accessible sex education. I went to Gallaudet University which is the only Deaf university in the world. While I was there, I was learning about everything from dental damns to the different types of condoms and how to put those on. Here, I got a full understanding of what safe sex meant—not just for heterosexual people, but for queer people.

Once I graduated, I started working with different sex education [organizations] and travelling to do Deaf outreach. I’ve been to many different schools where I’ve hosted workshops explaining different aspects of sex education and advocating to have that information available in sign language, whether that be in person or in the form of a blog with real visual examples to show body parts using sign language. Accessible sex education is something that I’ve been advocating for all this time… . For the Deaf community, it is so important to have sex education available in ASL.

Another concern I have when it comes to sex education is the question of who is teaching it. When it comes to the Deaf community, historically, our interpreters are the ones teaching sex education rather than Deaf people themselves. Now, sometimes interpreters aren’t comfortable with certain words or with certain contexts—so I’ve been hosting sex education interpreter training because if an interpreter is not comfortable with certain materials then it is going to have a huge impact on the children learning from them, because children can see the discomfort and the interpreter may be signing clearly. And as a kid, you’re confused—you’re not sure if you can ask questions when you don’t understand something because it feels so awkward in the room. So, to those who are teaching sex education or who are hiring sex educators for Deaf children: have a Deaf person there. They understand the full lived experience and they can make the language and the program accessible in a way that a hearing person never would be able to.

Andrew Gurza: I remember being in 9th grade health class watching the birthing video and learning how not to make a baby, and thinking… cool, none of this applies to me as a gay disabled person. I felt very out of step, and I had to learn about sex and sexuality on my own. When I officially came out as gay at 16, I remember seeing all of these pamphlets saying, “it’s okay to be gay” but there were no pamphlets saying, “it’s okay to be gay and disabled.” There was nothing for me in that regard, so I felt very isolated from both the gay community and the disability community. At 19 when I started trying to access my sexuality—going to bars, trying to meet guys and have a sexual experience—I was met with a lot of confusion, I didn’t have any resources to help me through that and I felt very alone. So, I decided after 10 years of doing Legal Studies at Carleton University in Ottawa that I wanted to start talking about my experiences of weirdness and sexuality because of the lack of education out there. Similar to what Sage was saying, I started going to different schools and universities and talking to student groups or LGBTQ+ groups, and I started writing for big news outlets, saying I have a story I want to share.

In terms of my education, though, I had to learn on the fly. I had to learn through having the experience, which can be really traumatic because there’s no one giving you any signposts or telling you it’s going to be okay. You are out there in uncharted territory, and no one knows how to help you navigate that. So, I felt very isolated in doing it and even now, when I do talks about sex and sexuality I’m often the only visibly disabled person in the room…

In terms of resources, one of the things that I’m working on through the company I started with my sister is creating sex tech for and by disabled people and we’ve created the first sex toy for people with hand limitations—it’s called the joystick and will be available to purchase in the new year [2022]. We’re really excited because there aren’t a lot of resources for physically disabled people who want to engage in sexual pleasure. Similarly, just as Sage was saying about all the greater sources online, we’ve created a resource with our company called “The Handi Book of Love, Lust and Disability” which offers stories from people who are disabled. I think it’s different from other resources out there because it doesn’t focus on how to have sex but rather tells us how sexuality and disability feels. And I think that’s a really powerful thing.

Ricky Varghese: I do research on sex and sexuality, and how people talk about sex and the language used when we talk about sex. I, much like the other panelists before me, didn’t have access to sex education in school as a young queer person. Sex was not something that was talked about at school, with respect to how we thought about it. In fact, there was a lot of silence surrounding sex… and a lot of discomfort in talking about it. So, much like other people I know, I learned about sex online and I learned about sex through friends. In terms of what I have learned as a social worker, and specifically, a school social worker—which is something I did in a past life—when you oppose sex education in the school system, you have to always assume that kids already have access to a lot of information.

And what I mean by “access” is that, especially in this moment, there’s a lot out there and there’s access to a breadth of information… some of it factual, some of it not-so-factual, but there is certainly discourse about sex within communities of young people. One always has to assume that there is discourse being produced about sex. And as an educator, one has to approach the conversations that young people have about sex, with a sense of humility, a sense of empathy, a sense of comfort… and a sense of wanting to educate, but also to learn from kids about what they already know. A presumption that kids know nothing at all about sex, or conversely, that they don’t have access to information about sex, is perhaps not the best way to approach a pedagogical or educational setting. And I encourage educators to really think about the perspective and knowledge that children have already, about how they think about sex or sexuality. I think that’s difficult to do in systems that are restrictive.

I’m also a psychotherapist in private practice, and so, one of the things that comes up often in exchanges that I have with colleagues is that conversations about sex don’t come easy for people. In fact, in a lot of my clinical practice, I find that adults still carry difficulties and discomfort when it comes to talking about sex, that they have perhaps had since a very young age. So I emphasize that it’s important to really create opportunities for people to talk about sex in a fully uninhibited, non-judgemental manner. One has to question why sex is something we don’t talk about often and wonder why sex is something that is silent in conversations… why sex is imagined as being bad. …There’s a general discomfort in processing our sexualities and we can observe this in both able-bodied and disabled people …

So, it’s important to think about how disabled bodies are viewed within conversations about sex and to think about and expand upon the conversations we have about sex. It’s important to think about what we understand as bodies that are desirable, and bodies that are understood as undesirable… and problematize that.

Nadia Abdel-Halim: [M]y discussion of my experiences with sex education might be a little bit different. I think that how I got into sex education, and specifically, sex education curricula for people with intellectual disabilities, is very much related to my upbringing. My brother is only two years younger than me and because of this, I think, like most siblings with that age gap, we compared our trajectories with each other pretty much throughout our whole lives. And, I remember that when my brother started getting to the age of puberty, there was a lot of fear-mongering that I did not experience as I was growing up. All of a sudden, doctors and therapists and teachers were all warning us about how when autistic men, or men with intellectual disabilities, reach puberty they suddenly have too much testosterone, and problem behaviors start pop up. So they said things like, “watch out for public masturbation, and watch out for sexual offending.” And I remember feeling uncomfortable that everyone was suddenly looking at my brother with this really sexual lens because to me he's my younger brother and he's just a kid, and he hadn't actually shown any of the behaviors they were referencing. And on top of that, none of the conversations we were having a very solution based… when you would ask, “okay, what are we meant to do?” They would just say, “well, let us know when it happens.”

Even as someone who received very little sex education—I think the extent of my sex education was watching Dr. Phil reruns, and just, like, talking with friends when the teacher went on break—I felt like something was wrong. But, these people were supposedly ‘educated in the field’ and they supposedly knew much more than a high schooler like me. And, it would be years until I learned that people with intellectual disabilities are far more likely to be victims of sexual violence than perpetrators… not only in their childhood but in their adolescence and adulthood. It would be even more years, not until I got some training as an assistant psychologist, that I learned that all tell-tale problem behaviors were actually considered tell-tale signs of sexual abuse in neurotypical children, and so the way that these behaviors were being interpreted so differently became really interesting to me. It really kind of sparked a fire in me.

During my master's I wanted to interview Ontario teachers, and I wanted to know why sex education wasn't taught and what their beliefs were about the sexuality of the students. When I had these conversations, one-on-one, overwhelmingly what I learned was that sexual behavior is policed. The teachers also talked about liability and administrative issues that pop up, and things like high turnover rate, and parents not agreeing with sex education. They also spoke to some of the myths…about sexuality and people with disabilities. And all of these seem to underlie the issue and I want us to kind of take this conversation, beyond three-star hotel conferences, to other academics. And so, I started holding panels in public, and I was actually holding panels in Cairo, because that's where I was, and that's how I joined [a project] called “My Body is My Body.” And, that team was concerned with trying to improve sexual autonomy for children, specifically primary school students. And the way that they did that was by using these horribly catchy songs and changing the language to colloquial Arabic, colloquial Egyptian, and the people looked more Egyptian in the video as well.

Now, I have to say one thing I've learned as a researcher and as a special education teacher, is that my outlook can only be validated by person-first experiences. So, I think the thing that made me most proud was when I was able to develop this output and then saw it summarized beautifully by Cal Montgomery (2021) who has lived experience as a nonverbal person with an intellectual disability. And he started talking about all the questions that I didn't know how to answer, like: What does consent look like if you're nonverbal? What does that look like if you're a nonverbal individual with an intellectual disability? And some of the things that came out, and where I notice commonalities, indicate that a sex education tool for people with intellectual disabilities does not only need to teach, but to help unlearn the lessons that people with intellectual disabilities are taught from a very young age, which is that everyone who is neurotypical is an authority on what correct behavior is and on what bodies should do and look like. Because while we teach this implicitly so that they can become involved in the structures and systems that we've put in place, and I say this as someone who is not disabled… while we do this so they can be seen as “compliant,” it’s so dangerous to their understanding of their own bodily rights.

The other thing is that we really do need to develop and co-develop explicit visual and clear sex education tools, which means no complex euphemisms or metaphors about birds and bees but rather using language that's actually going to be used in public. This harkens back to what Ricky said… and the idea that, if they're going to be encountering these topics in the context of slang being used then slang needs to be taught. And one thing that I think is missing from a lot of sex education curricula currently is the fact that knowledge needs to be reinforced, especially in the environments that it’s going to happen in. So, this might entail going into public, and having exercises to do to promote this idea of sexual citizenship is important. … For example, a lot of people with intellectual disabilities don't have access to privacy, in the ways that we often conceptualize private to be. And so that's something that's extremely important, knowing what gatekeepers are doing, and how to allow people with intellectual disabilities to advocate for themselves and become the authorities on their own sexual understandings. And lastly, the idea of sexual desire is equally important… it's humanizing and it should really be at the crux of everything we do.

Fran Odette: I first became really interested in the work around disability and sexuality when I was doing programming for an organization called The Disabled Women’s Network in the early 1990s. At that time, it was the only organization that was led by disabled women, who were actively working on addressing issues of inequality, both within the women's movement as well as in the disability rights movement. So, they were seeing the intersections around disability and gender at that time and noticing how oftentimes disabled women were not included in the disability rights movement, and how gender was not considered important in the disability rights movement… or that considering gender would somehow fracture the larger issues that the movement was fighting for. And the disabled women's movement really was about bringing those experiences together and recognizing that the ways that we think about gender, and the ways that we think about disability are not experiences that we can compartmentalize but are a part of the broader complexities in our lives.

In my own lived experience as someone who grew up in a family, that didn't talk about disability and sexuality… it was never imagined that I would be in a relationship. And when I was going to elementary school, I went to a segregated school …and I don't remember any time that we talked about sexuality and how that would be part of our lives. The only time I ever remember talking about sexuality was when I had a teacher who really recognized our personhood and recognized that against the backdrop of a very paternalistic way of thinking about child development, specifically for children with disabilities. I remember, this one time, where she said, "Okay, let's talk about sex" and proceeded to close the door. And this action kind of alluded to us that this would be a safe space, but that we couldn't talk about sex outside of the classroom. I can imagine that for her and her colleagues talking about disability and sexuality in school was very much a taboo issue, and it was a taboo issue for parents… it was not something that was broached with parents, really.

I later, then, got a chance to do some work with Cory Silverberg. Cory was the co-owner of a sex-positive sex store here in Toronto called "Come As You Are” add it was an amazing space and Cory was so committed to ensuring that that space would be a place that felt safe for anyone to come in and ask questions about sex, about sexuality, about sex toys… you know, if I had limited mobility, how could I use particular kinds of sex toys? All the staff were trained on being disability-inclusive and being prepared for questions and able to respond in a way that would not be shaming or leave people out.

I worked with Cory around issues around sexuality that were arising for disabled folks who were using attendant services. For many folks with whom we worked with on this project, the topic of sexuality was not part of their care plan within the organization. And many times, individuals who were in supportive housing, who were using attendant services, wanted to be sexual, whether that was with themselves, or with a partner or a lover…but they were having to deal with the bureaucracy of a system that was quite fearful of consequences of acknowledging disabled people's personhood around sexuality and providing supports for people to be sexual. When we were doing this project we were hearing from attendants who recognized that their clients were sexual but knew that, if their colleagues or the management found out, that there would be some consequences for them. So, the flip side of that is, attendant users might have to wait for that one attendant who they knew to be ‘okay’ with requests for sexual support, to come on their shift in order to ask for support with respect to sex and sexuality—to ask if they can be set up with a vibrator, or to ask for help getting dressed in a sexy outfit because their lover is coming over.

My own experience has shown me that disabled kids do not get access to sex education in the same ways as their non-disabled peers and traditionally, or historically, many aspects of sexuality weren’t touched on at all—issues around gender identity, sexual orientation, and kink, for example. So, queer kids as well as disabled kids were not seeing themselves represented in the curriculum. I think many of us did not see that we existed and really wondered about our futures. I think many of us remain very much invisible in the textbooks. I think what we are seeing now, with this existing government, is a very repressive approach to sexuality. Our previous [provincial] government had brought in a very progressive curriculum which spoke to gender identity, sexual orientation, sexual violence, and those things are not taken up in the same ways within our current curriculum. I do think that ableism has run rampant through the design of this new repressive curriculum and it does support ableist thinking, which positions disabled people as asexual and without sexual desire. And on the flip side of this is the myth that if we actually give young people, with and without disabilities, information about sex, that they'll be suddenly be having sex all over the place. Well, here is the news folks… we already are! So, why not give us information that allows us to make informed decisions about our experiences about the issue of consent… so that there is a recognition of our sexuality, of our desire to explore sexuality in a sex-positive way, rather than in a way that frames sex and sexuality as something that we must be protected from. And I think that is how sex continues to be framed in mainstream schooling, especially for people with disabilities.

I think that when our lives are not spoken about, or we can't see ourselves in the pages of the learning that we're doing, that those of us who are disabled or part of the Deaf community, and/or queer identified, or thinking about our own gender identity… BIPOC, queer, and trans and disabled activists and communities have a long history of being erased… and have survived in the face of many efforts to ensure that we don't. I appreciate that that might feel quite harsh. But, I think it's important for us to, in this time, in thinking about Black Lives Matter in thinking about trans rights, in thinking about a lot of communities that have historically been pushed to the side, that now our time has come to really be asserting, who we are and pushing for our rights in all aspects, which includes our own sexualities.

References

- Montgomery, C. (2021). Dear Parents who want to keep their nonspeaking children safe as they

go out into the world. Communication First [Guest Blog]. Accessed 25 March 2022:

https://communicationfirst.org/dear-parents-who-want-to-keep-their-nonspeaking-children-safe-as-they-go-out-into-the-world/ - Campbell, M., Löfgren-Mårtenson, C., & Martino, A. S. (2020). Cripping sex education. Sex

- Education, 20(4), 361-365. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2020.1749470

- Campbell, M., Löfgren-Mårtenson, C., & Martino, A. S. (2020). Sexuality, Society and Learning [Cripping Sex Education: A Themed Symposium]. Sex Education, 20(4).