Behind the Paintbrush: Understanding the Impact of Visual Arts-Based Research (ABR) in the Lives of Disabled Children and Youth as well as Methodological Insights in ABR Application

Fiona J. Moola

School of Early Childhood Studies, Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, Toronto, Ontario

Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

Rehabilitation Sciences Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontarios

Ron Buliung

Department of Geography and Planning, University of Toronto, Mississauga, Ontario

Stephanie Posa

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, Toronto, Ontario

Rehabilitation Sciences Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

Nivatha Moothathamby

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, Toronto, Ontario

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

Roberta L. Woodgate

College of Nursing, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Nancy Hansen

Disability Studies, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Tim Ross

Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, Toronto, Ontario

Rehabilitation Sciences Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

Department of Geography and Planning, University of Toronto, Mississauga, Ontario

Introduction and Background

Arts-based research (ABR) makes many promises, including the opportunity to engage with embodied ways of being and knowing, raise social and political concerns, as well as to address novel, participant-led inquiries. In this critical narrative review of the literature, we examine how disabled children and youth employ ABR methods in research contexts by carefully examining studies that use visual ABR. A secondary aim is to glean methodological insights from the application of ABR to the lives of disabled children and youth to help foster this critical dialogue. We decided to undertake this narrative review of the literature to better understand how ABR is used in pediatric disability contexts. Pediatric disability is characterized by an excessive focus on positivist methodologies as well as biomedical regimes (Gibson, 2016). Given that ABR may generate creative, inclusive, and novel ways of engaging in research with disabled children, we thought that such a review was important to undertake. We are interested in ABR scholarship for a number of reasons. Since disabled children and youth are often exposed to biomedical and rehabilitative therapies (Gibson, 2016) and research methodologies, we are interested in the affective, emotional, and embodied possibilities afforded through the ABR approach for this group of young people.

In our review, we found that disabled children and youth used ABR to illuminate the significance of educational and social issues in their lives. They also used ABR to allude to the importance of peers, friends, and other important social relationships. Most of the ABR pediatric scholarship was centered around autistic children and youth. There was also a tendency for researchers to work with older children and youth with little attention to the arts in the context of early childhood disability. The most commonly employed ABR technique was photovoice. Most authors used ABR as an adjunctive method to other more commonly employed techniques and few teams used ABR for knowledge generation. Few teams declared their onto-epistemological positions. Although there are many excellent adult ABR studies, we found few reviews of literature undertaken with disabled children that are grounded in critical frameworks.

In Euro-Western academic traditions, ABR is currently understood as one nascent methodological approach housed within the qualitative research canon. James Hayward Rolling Jr. defines arts-based research as a research paradigm that can communicate with and augment more traditional social sciences and educational methods. ABR is flexible and comprised of both practice-based and theory-building methodologies. ABR can blend the arts and sciences in naturalistic inquiries. ABR is also an innovative method that can lead to new discoveries (Rolling, 2013). ABR encompasses emotion, desire, and intuition. Our ABR definition is also informed by O’Donoghue and Rolling who understand ABR as the production and/or dissemination of knowledge through the use of the arts (O’Donoghue, 2009; Rolling, 2010). During the qualitative “turn” in research, qualitative scholarship was posited as a means of speaking back to the dogma of quantitative research approaches (Jensen, 1991). Similar to the qualitative turn in research that took place a few decades ago, ABR represents a new direction that can speak back to the tyranny, or hegemony, of textually-based methods in the academy. Indeed, ABR poses a counter-hegemonic discourse within the academy (O’Donoghue, 2009). For example, for non-verbal people, ABR might provide novel communication pathways that do not rely on speech for participation (Krøier, Stige, & Ridder, 2021). ABR can lead to the generation of new questions, while also inspiring novel sociopolitical concerns. When used in a critical and emancipatory way, ABR can serve as a tool for addressing systemic inequality (Visse, Hansen, & Leget, 2019). ABR is characterized by numerous artistic genres, including drama, music, and dance. However, in this paper, we only collected studies on visual ABR by purposefully excluding the other genres in the pool of final articles. This enabled us to conduct a more focused review on visual ABR only. Given the increasing specialization of academic disciplines during the mid-20th century, the arts and the liberal arts have been marginalized in favour of a focus on more traditional subjects. Detels (1999) suggests that it is necessary to remove ABR from its long history of marginalization.

A Brief Note on Definitions and Literature Reviewed: Of note, art therapy, ABR, and arts education are very different. Arts education and art therapy are disciplines and arts-based research is a methodology. However, ABR is often used as a methodology by both arts educators and art therapists (Potash, 2019). While ABR refers to the production and/or dissemination of knowledge through the arts, a central hallmark of art therapy is that it is “routinely administered by a qualified practitioner as a means to confront the maladaptive beliefs, experiences, and behaviours of clients” (Kontos, Grigorovich, & Colobong, 2020, p.189). In an attempt to critique the notion that the arts can be used to “purge” hidden internal conflicts, our review engages the ABR literature and not the art therapy literature. Although we cannot capture the breadth and complexity of arts education in a simple paragraph, we feel that it is important to briefly differentiate arts education and ABR. We have adopted a current arts education definition that does not consider it to be a monolith. First, arts education includes domains, consisting of arts curricula, such as visual arts, theatre, dance, or music. This may also include digital media and creative writing. Arts education is also defined by particular characteristics, which include the qualities of each domain. For example, dance is highly interpretive. Arts education is also highly influenced by culture and temporal periods. Finally, intersections may exist between arts education domains and genres. Arts education can also be used to teach about subjects unrelated to the arts as well (Holochwost, Goldstein, & Wolf, 2021). In our paper, we are not considering arts education. Rather, in an effort to seek out embodied, affective, and emotional methodologies that transcend a focus on biomedicine and rehabilitation in the lives of disabled children, we are only considering literature where authors claim to have used ABR in the context of childhood disability research. We recognize that as a nascent methodology, ABR has many interpretations and scholars do not all understand ABR in the same way. ABR can offer many possibilities and promises, like engaging embodiment and addressing social and political concerns.

Of note, we are considering the use of ABR in pediatric disability research contexts. Research contexts are heavily geared toward the production of knowledge. Of course, ABR in education, health care, or community contexts may greatly differ. For instance, they may not be as attentive to knowledge production. For instance, ABR in community-based contexts may be more focused on the role of the arts in community engagement (Giles, Curran, Crossman, & Moola, 2020).

Before undertaking our review on ABR and its use with disabled children, it is important to situate our thinking about disability. Indeed, ABR and disability are connected given the potential for ABR to offer more inclusive participatory options for disabled children and youth. Here, we take disability to be a bodily and social phenomenon that cross-cuts both structural and embodied dimensions. In this regard, we recognize the disabling social structures (Oliver, 2013) that disabled people face every day – such as lack of access to work, school, and play – at the same time as we also acknowledge the pain and reality of disability as deeply embodied ways of being in the world that mark and shape the flesh (Imrie, 2004). Thus, unlike some disability scholars who purport that disability is only environmental, we in no way deny the corporeality of disability. Further, some members of our research team identify as disabled people or people with disabled family members. Within disability studies and the disability constituency, identity-first language is preferred. While we recognize the contentious nature of disability language, we do not regard disability as secondary to personhood as in person-first language. We also acknowledge that the separation of the person from condition perpetuates stigma and the false notion that these embodiments are inherently negative (Botha et al., 2021).

Self-reflexivity: Although self-reflexivity is a somewhat contentious issue, some scholars consider it a necessary part of scholarship, most especially within the qualitative research tradition (Pezalla, Pettigrew, & Miller, 2012). Our research team is comprised of students, University professors, and research scientists. One of our members is an artist and three others have extensively used arts-based research in the context of their research practice. All of us have worked directly with disabled children in the context of hospital environments. Additionally, on our team, we have lived disability experience, both from the perspective of living with disability and parenting a disabled child. Some members of our team also identify as racialized people, which has drawn our attention to the Euro-centricity inherent in the arts. Because of our subjective positions and disciplinary expertise, we recognize that we bring particular assumptions about the arts that are inseparable from the scholarship we have undertaken. For instance, within the context of the biomedicalization discourse that disabled children are so often exposed to in hospital spaces, we do believe in the inherent benefits of the arts in terms of opening up new ways of seeing and being.

Important research already exists at the intersection of disability and ABR. Several arts-based research projects have already been undertaken in the discipline of disability studies. For instance, grounded in a disability culture, disability justice, and intersectionality approach, Jones and Collins (2020) created student-led documentaries that drew attention to important disability themes, such as institutional survivorship and accessible cities, without perpetuating damaging stereotypes. The project also furthered an understanding of “crip” time, that is, a recognition that disabled and chronically ill people may have different temporal experiences than able-bodied people. Similarly, Douglas, Rice, and Siddiqui (2020) employed a multi-media storytelling approach with women and trans people that allowed them to generate a power counter-discourse in response to hegemonic narratives of disability and health care. Sensitized by feminist and post-humanist theories, they argue for an approach that embraces illness, disability, and pain as a component of what it means to be human. Allen (2019) considers digital and narrative methods as a part of ABR. Using these methods in the context of an academic dissertation, Allen (2019) employed ABR to explore issues of disability and identity. The stories that were created with participants helped to speak back to compulsory able-bodiedness. In a truly innovative paper that blends the arts and movement, Eales and Peers (2016) used an ABR approach within the context of adapted physical activity to draw attention to how the arts can be used to enrich the way we understand and unlearn movement.

Important disability and ABR work exist that has drawn attention to the ethical tensions that plague this field. For instance, in the context of ABR, Rice, LaMarre and Mykitiuk (2018) draw attention to inherent ethical tensions between research ethics boards’ insistence on confidentiality and the need for disabled participants to be acknowledged as artists. They also suggest that issues of voice, representation, and aesthetics must be considered as part of the ethical terrain when using ABR with disabled people. For instance, reflecting on their own project, known as Project Re-Vision, Mykitiuk, Chaplick, and Rice (2015) note that disabled people have often been exposed to demeaning and pejorative labels and stereotypes. Reflecting on ethical arts-based engagement through their project that employed digital storytelling and drama, the authors discuss how the arts can be used to resist and speak back to such damaging labels. Their work is imperative to the arts-based disability nexus for drawing attention to the ethical issues inherent in this process.

Previous ABR Reviews of Literature:: In addition to these important ABR and disability scholarly works, reviews of literature reviews focused on the use of ABR in health care have been conducted. For instance, in their systematic review of the literature concerning ABR in health, Fraser and al Sayah (2011) found that ABR is primarily employed in health care as a tool for knowledge generation and knowledge dissemination. They also reported that the vast majority of studies focused on visual ABR. Similarly, Boydell and colleagues (2012) undertook a scoping review of arts-based health research. They found that ABR was characterized by an array of genres and used to explore many different substantive topics. The arts were mainly regarded as a way in which to enrich the communication process with participants and to promote research engagement. Further, the use of arts-based data collection methods among pediatric participants in health research was also examined (Driessnack & Furukawa, 2012). Results indicated that there is a paucity of ABR methods used in health research, as only 19% of included studies examined a health topic with ABR (Driessnack & Furukawa, 2012).

Despite the important contributions of past literature reviews, thus far, no scholarly reviews of literature have specifically explored how disabled children and youth utilize ABR or the methodological insights that may arise from engaging this topic. There is also no child and youth-focused review which speaks to the adultist nature of existing ABR scholarship. In this regard, the literature has tended to maintain a focus on adults rather than children and has not engaged specifically with the concept of disability. A review of literature specifically aimed at understanding such uses and methodological insights in ABR in the lives of disabled young people is urgently needed. First, for disabled young people, the arts may enhance existing communication options (or create new ones) beyond verbal and textual/written communications. Secondly, disabled children are often exposed to bio-medicalized environments and rehabilitative therapies that try to establish or re-establish normative functioning (Barron, 2016). There is a need to examine modalities such as ABR that are not pursued for rehabilitative or therapeutic means. Further, disabled children may have less access to community-based opportunities for artistic participation and leadership (Law et al., 2007; Penketh, 2017; Wexler, 2009). In this regard, they are rarely “Behind the Paintbrush”, as the agents and authors of their own artistic productions. Access to art-making opportunities are extremely limited for young disabled people (Wexler, 2016). As part of the overall aim to increase the engagement of disabled people in the arts, it is important to understand how arts-based methods impact them and, conversely, how the presence of disabled children and youth can enrich arts-based activities and communities. Finally, given that ABR can be used for emancipatory and critical purposes to raise awareness of social injustice (Visse, Hansen, & Leget, 2019), intersecting ABR and childhood disability could help to politicize disability. The purpose of this narrative review of literature is to examine how disabled children and youth utilize visual ABR in research. A secondary aim is to explore methodological issues in ABR studies conducted with disabled children and youth. Our search strategy is described below.

Methods

We selected a review methodology known as a critical narrative review of the literature as described by Gastaldo and colleagues (2018). Narrative reviews of literature are flexible and inclusive of numerous research design types (Culley et al., 2013). They generally allow for a rich and literary style of writing and discussion that is more than merely descriptive. Further, the critical narrative review type allows us to critique, trouble, and problematize deeply entrenched notions in the literature or problematic ideas and assumptions. For example, the underlying association between the arts and Euro-Western ideas and cultures is something that a critical review of literature allowed us to problematize, trouble, and explore.

Theoretical framework:We adopted a critical disability studies conceptual lens to guide this critical narrative review of the literature. Disability studies in the latter 20th century was concerned with drawing attention to the social, structural, institutional, and ideological structures that gave way to the exclusion of disabled bodies in society (Goodley, 2013). These earlier disability theory sentiments were underpinned by Marxist theory, given the historical exclusion of disabled people from conditions of work. Disability was, then, a materialist problem. The emergence of a critical disability studies approach, however, has entailed moving beyond social versus medical model debates and entering into a new sphere that is characterized by embracing previously disregarded disciplines and including queer, feminist, and post-colonial theories as well (Goodley, 2013). It was also borne out of a desire to break with the totalizing and universalizing dominance of the social model and the excessive focus on society (Hughes & Paterson, 1997; Shakespere & Watson, 2001), with some suggesting that disability is so much more than this. Critical disability studies in the post-modern world are marked by an emphasis on the discursive, cultural, and relational production of disability experiences, a recognition of intersectionality within disability experiences, and a great emphasis on deconstructing the ableist norms that give rise to disability in the first place (Goodley, 2013). Critical scholars have also drawn attention to the role of the symbolic and the ways in which disabled bodies often come to harbour ableist anxieties and insecurities about the frailty of the body. While recognizing that the separation of impairment and disability was needed a few decades ago, critical disability studies was also a response to growing dissatisfaction with the disavowal of the body in disability studies (Goodley, 2013). Indeed, sometimes, the disabled body can be tragic, a site of pain and oppression. Critical scholars have troubled this somatophobia and invited the biological body back into contemporary disability conversations (Goodley, 2013; Hughes & Paterson, 1997). Relatedly, phenomenological critical scholars such as Tanya Titchkosky have drawn attention to how disabled bodies are materialized in the first place. Thus, critical disability studies today are marked by disciplinary fragmentation and a concern with the symbolic, discursive, material, and intersectional aspects of disability. We used this theory to help colour and guide our understanding of the literature, with a view to unpacking ableist assumptions about disabled children and the arts (Goodley, 2013).

Search Strategy

Peer-reviewed studies and other literature on the use of ABR among disabled children, as well as arising methodological insights, were identified. To formulate a search strategy, a preliminary consultation was held with the Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital academic librarian in which we drafted a list of subject headings and keywords. Some of the subject headings we drafted were: arts-based research, photovoice, body mapping, drawing, disability, children, followed by accompanying synonyms.

Using a combination of subject headings and keywords, we formulated a search chain comprising 36 terms. Upon receiving feedback from the academic librarian and our research team, we used our search terms to perform our search. To combine our searches, we used “AND” and “OR” Boolean terms, as well as truncation (*) and adjacency (adj or N or NEAR) functions. This allowed us to achieve more breadth when searching keywords. Five electronic databases were searched, each of which was accessed through the Toronto Metropolitan and University of Toronto libraries webpage: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, SCOPUS, and Sociological Abstracts. Interested readers should contact the first author for more detail on the search strategy.

Screening and Selection of Relevant Articles

Our research team compiled a list of inclusion and exclusion criteria to guide our selection of full-text articles. The articles generated by each database were exported to EndNote X9 for Mac, where the duplicates were removed, which resulted in a total of 141 articles. We limited our search to full-text articles published in English, with no date range specified. We included studies with participants aged between one to 18 years old with a mental or physical disability. We adhered to the definition of child and youth provided by The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which states that a child is anyone between one and 18. Included studies had to clearly demonstrate the application of visual ABR techniques and a commitment to ABR principles. Here, we recognize that ABR is an ever-evolving paradigm and that ABR publications, like our own, must, in some way, contribute toward methodological advancements. Following James Rolling Jr, we included visual ABR studies that addressed new questions that could not be answered through traditional scientific paradigms. We also recognize ABR as one grounded in arts practices and deeply concerned with aesthetic questions. We also recognize ABR as a practice-based methodology that is firmly rooted in creativity and knowing (Rolling, 2010). We did not exclude any studies based on geographic region, gender, ethnicity, culture, or race. We excluded studies that centered on performative and textual art forms such as dance, music, theatre, poetry, and creative writing unless these art forms existed alongside the use of visual arts forms. The review of abstracts and full-text articles was undertaken by three team members.

Data Analysis

In order to generate findings, we undertook a thematic analysis in the context of our critical narrative review of the literature (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Culley et al., 2013). This entailed engaging in a process of open free coding where recurring issues across the articles were first coded initially. In phase two, these codes were grouped into larger categories that encapsulated the same semantic meaning. We then refined and adjusted category names into themes. The substantive findings from our critical review of the literature are reported below.

Results

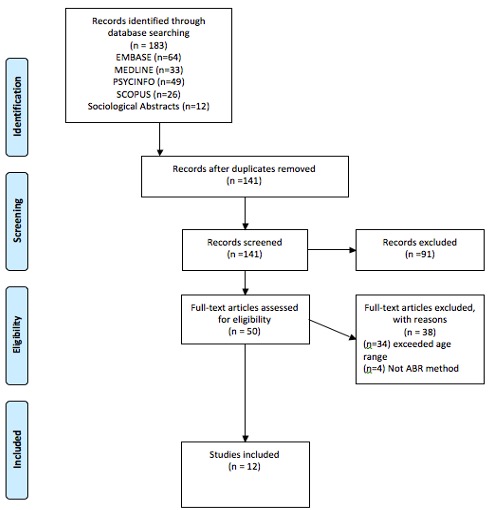

The search generated a total of 183 articles. These articles were exported to EndNote X9 for Mac, and, once duplicates were removed, a total of 141 articles remained from the search. Using these criteria, the initial 141 articles were reduced to 50 articles. Of the 50 full-text articles reviewed, 12 were included in the final analysis. Thirty-four studies were excluded as the participants exceeded the range of 1-18 years old. Four studies were excluded because they did not utilize arts-based research methods, but rather a quantitative form of computational body-mapping. This left a remainder of 12 articles to undergo data analysis.

See (Fig.1) for a PRISMA diagram, which overviews the search and selection process.

Characteristics of the Papers

Included studies were conducted in the United Kingdom, Australia, the United States, and Canada.

| Article | Country | Population | Objective | Research Design | Disorders | ABR Methods & Purpose | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capewell, 2016 | United Kingdom | Three "young people" ages 10-14 | To explore the experiences (in an educational context) of young people living with flue ear, and their mothers | Qualitative | Glue ear | Photovoice: To allow participants to reflect on their situation and issues that they deem as personally relevant/young people and mothers | Participants felt that more adaptations were needed in classrooms to help minimize hearing loss impacts. Educational Professionals lack awareness of the soecial, behavioural and cognitive effects of glue ear on their students. |

| Danker, Strnadova & Cumming, 2017 | Australia | 10 students between 10-15 years old | To explore the conceptualization of student wellbeing from the perspective of teachers, parents, and students with ASD. | Qualitative | ASD | PDPE: to engage students with ASD meaningfully in researchl to support communication, to decrease barriers. | Benefits of using PDPE: 1. Offered a sense of empowerment and contrl 2. Accessibile as no reading or writing is required 3. Access and insight into various settings that researchers would otherwise not be exposed to. 4. Acquisition of new skills: social and photography-based 5. Increased research engagement 6. Enhanced communication Challenges of using PDPE: 1. Still required some verbal skills to communicate interpretations etc. 2. Flexibility on behalf of researchers to deal with unique needs, school policies, etc. 3. Time, effort, and resources 4. Collaboration with teachers was at times, necessary to help participants 5. Teacher influence 6. Ethical considerations |

| Danker, Strnadova & Cumming, 2019 | Australia | 16 participants, ages 13-17 | To explore the merits of employing participant driven photo elicitation through a study examining well-being of students with autism spectrum disorder(ASD) | Qualitative: Photovoice; 2 Interviews | ASD | Ohotovoice-empowerment, (b) accessibility, (c) ability to record various settings, (d) development of various skills, (e) increased engagement in research and (f) enhanced ability to communicate | In the photos, well-being was conceptualized as emotional, social, academic and "well becoming." Photos depicted barriers to wellbing as being sensory, social, and learning-based. Ways to enhance well-being were depicted in the photos. Ex. Having access to technology, extracurricular groups, food, counsellors, peers and staff at school. |

| Feldner, Logan & Galloway, 2018 | United States | two children, ages 4 and 5, and their families. | To explore experiences surrounding powered mobility provision and early use. | Qualitative | Cerebral Palsy | Photovoice: a "tangible" representation of the child and family's perspectives and is accessible especially for children with communicative difficulties. | Photos reflected 4 main themes: (1) Dys/function of Mobility Technology (2) How device mediated participation in play and daily life (3) The emergence of Self-confidence, independence and advocacy (4) Interplay between family and mobility device industry. Ex. ideas of choice, model logistics, decision making power, funding policies etc. |

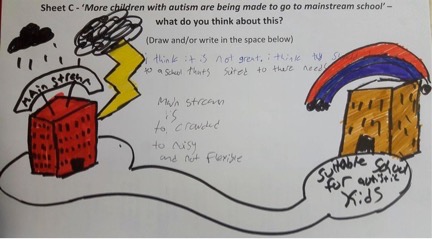

| Goodall, 2020 | United Kingdom | Twelve "young people" ages 11-17. | To explore the notion of inclusion in educational contexts among young people with ASD. | Qualitative | ASD | Draw and Write: to acquire gain 'authentic' knowledge about children's experience, to provide appropriate and engaging opportunities for expression, to increase research accessibilitiy and ensure children's participatory rights could be exercised by offering multiple means of representation. | Participants felt inclusion relied on notions of belonging and being valued. Further, they felt inclusion can take place in any type of school, is not confined to mainstream schools. Many participants verbally and visually expressed that there are barriers to mainstream inclusion for children with ASD, such as teachers not being educated about ASD, and the presence of sensory challenges in classroom environments etc. |

| Ha & Whittaker, 2016 | Australia | 9 "young people" ages 10-17. | To use photovoice to examine the needs and experiences of children with ASD | Qualitative | ASD | Photovoice: used to engage and empower young people with ASD. Photovoice was modified to suit abilities and interests of children with ASD | Content analysis of photographs revealed the presence of: A. Objects (toys, dolls, pens, books etc.) B. People C. The Self Content analysis was found to be insufficient on its own. Ethnographic observations and interviews with participants, parents, and caregivers enhanced the interpretation of photos. |

| Mah, Gladstone, King, Reed & Hartman, 2020 | Canada | 18 "children" | To explore children's conceptualizations of concussion through the drawing and interviews. | Qualitative | Concussion/mild traumatic brain injury | Drawing: used for knowledge generation co-construction suited to an interpretivist framework. - Not used because it is child friendly or only avenue for communication - Used as an adjunct to interviews and used as prompt during interview |

No results reported *Methodological Insights: ABR can be used to elicit children's first-hand accounts of their experience, and to co-construct knowledge with researchers. ABR is not a "catchall solution". AbR must be used critically, based on research context, should be used in conjunction with traditional methods, and should be interpreted with child's input. |

| Mamaniat, 2014 | Unknown | 8 "children" ages 13-14. | To use photo journals to explore the experiences of children with learning difficulties in an English special school. | Qualitative | "Learning difficulties" | Photo Journals: used to enhance communication and active engagement and empowerment to avoid power differentials. | Four themes were elicited through photo journals and Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis: A. Togetherness and Belonging: Friendship and community at school B. Relatedness of Experience: School entwined with personal interests C. Positive Effects of the School Environment: School as valuable, engaging D. Idiographic existential experience: School was tailored to their individual needs |

| Obrusnikova & Cavalier, 2011 | United States | 14 individuals ages 8-14 | To use photovoice to examine barriers and facilitators of after-school physical activity among children with ASD. | Mixed Methods | ASD | Photovoice: To elicit children's perspectives. | Participants reoported 143 (44%) barriers and 181 (56%) facilitators. The most frequently reported barriers and facilitators were as follows: A. Intrapersonal Barriers: playing video games, feeling tired or bored, watching tv etc. B. Intrapersonal Facilitators: feeling rewarded, playing team sports. C. Interpersonal Barriers: lack of peer partners, lack of transport D. Interpersonal Facilitators: doing chores at home, friends and physical activity. E. Community Barriers: Lack of activities available F. Community Facilitators: Parks and playgrounds available |

| Okyere, Aldersey & Lysaght, 2019 | Canada | 16 children ages 9-16 | To understand the experiences of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities, surrounding learning within inclusive scohols. | Qualitative | Intellectual and developmental disabilities | Draw and Write: to engage participants, to facilitate participation | Children’s experiences in inclusive schools were in line with 3 themes: 1. Individual characteristics: Whether participant identified as having disability, how they compared themselves to peers, their specific characteristics and varying abilities (i.e. behavioural challenges) that impacted experience in school. 2. Environmental Characteristics: Accommodations and modifications to school environment, support received at home etc. 3. Interactional patterns: Challenges experienced including corporal punishment for slow performance, victimisation and low family support relating to learning. |

| Weiss et al., 2017 | Canada | 5 participants ages 13-33* *Data segregated according to parameter of age, therefore could decipher results specific only to those under 18. |

To surrounding participation in sport (Special Olympics) from the perspectives of athletes with intellectual disabilities | Qualitative -Photovoice -Interviews |

Mild to moderate intellectual disability | Photovoice: Used to facilitate communication and to foster empowerment | Two themes revealed through photographs: 1. Connectedness: to other athletes and coaches 2. Training in sport: technical aspects of sport, perseverance, competition and awards |

| Zilli, Parsons & Kovshoff, 2020 | United Kingdom | For participants ages 11-15, and 11 staff from specialist school | To explore the practices that facilitate participation of ASD children in educational decision making in school | Qualitative | ASD | Photovoice: used to support contributions of children in research. | Three main themes that facilitate participation. Access: to the classroom and curriculum using notions of flexibility. Achievement: Importance of focusing on what learners can do and how to facilitate achievement Diversity: Mutual recognition and acceptance between pupils and staff |

One research team did not report on where their study was conducted (Mamaniat, 2014). In this way, non Euro-Western countries were not represented in the ABR and childhood disability literature. The types of impairments reported included glue ear, autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, concussion and mild traumatic brain injury, learning difficulties (Mamaniat, 2014), and intellectual and developmental disabilities. Thus, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was overrepresented. The studies were mainly qualitative in nature or of a mixed-method design type. The age of the participants in the studies ranged from 4 to 18 years of age, with the majority of studies focused on later childhood to adolescence. Reported sex included males and females. Alternatively, sex was not reported and to our knowledge, no studies collected information on gender identity. Reported race included white, Asian, and African. Alternatively, race was frequently not reported. Reported ethnicity included British and Filipino. Alternatively, ethnicity was frequently not reported.

| Study | Gender | Race and Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|

| Capewell, 2016 | Two females, one male. | "White, British" |

| Danker et al., 2019 | 15 males, 1 female | Not reported |

| Danker et al., 2017 | 10 males | Not reported |

| Feldner et al., 2018 | 2 males | Caucasian and African American |

| Goodall, 2020 | 10 males, 2 females | Not reported |

| Ha & Whittaker, 2016 | 7 males, 2 females | Not reported |

| Mah et al., 2020 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Mamaniat, 2014 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Obrusnikova & Cavalier, 2011 | 12 males, 2 females | Caucasian, Asian, Filipino |

| Okyere et al., 2019 | 8 males, 8 females | Not reported |

| Weiss et al., 2017 | 4 female, 1 male | Not reported |

| Zilli et al., 2020 | 4 males | Not reported |

Themes

The use of ABR in the lives of disabled children and youth helped to reveal important areas of interest and activities in their lives, such as the educational issues and social relationships. These important areas of interest and issues are described below.

a) Illuminating educational issues:Engaging in ABR helped disabled children and youth to better reflect on their educational experiences, including positive and negative encounters. This was a dominant theme and was reported in 8 of the 12 studies. Photovoice is a participatory action research (PAR) method. Using cameras, a group of community-members takes photographs of a particular theme. Subsequently, photos are used to generate discussion. The issues arising from photovoice are often used to communicate to policymakers and other personnel to raise awareness of social issues in the lives of marginalized communities (Gubrium & Harper, 2016). For instance, through photovoice, participants demonstrated that education professionals often lacked awareness about the social, behavioural, and cognitive effects of disability on their learning (Capewell, 2016). Photovoice also allowed the researchers to better understand how to enhance well-being among children and youth with ASD in the context of education, by having access to technology, extra-curricular groups, food, counsellors, peers, and staff at school. However, many of the participants visually and verbally expressed that they face many barriers to mainstream school inclusion in the context of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Danker et al., 2017; Goodall, 2020). A lack of peer support at school was also reported as a barrier (Obrusnikova & Cavalier, 2011). Such barriers included interacting with teachers who were not educated about ASD, as well as experiencing sensory challenges in the context of school environments. Through photovoice, participants also made it clear that more adaptations to school environments are needed (Capewell, 2016). However, in one study, photovoice was used to reflect upon positive experiences at school, such as deriving a sense of togetherness and belonging, relatedness of experience, the positive effects of the school environment, and the school experience being tailored to meet individual needs (Mamaniat, 2014). Through interviews and the draw-and-write technique, Okyere (2019) found that inclusive experiences at school were influenced by the presence or absence of disability, social comparison to others, as well as the ability level of the child. Zilli (2020) found that participation in school environments was influenced by attentiveness to diversity, achievement, and access to the curriculum. Methodologically, photovoice also exposed researchers to the educational challenges disabled students face at school. This is knowledge that researchers otherwise would not have been able to access (Capewell, 2016; Danker et al., 2017, 2019; Goodall, 2020; Mamaniat, 2014; Obrusnikova & Cavalier, 2011; Okyere et al., 2019; Zilli et al., 2020). Although authors did not report on their level of participant engagement, ABR allowed participants to carefully reflect on their educational experiences.

b) The importance of the social world for children and youth:In 11 papers, ABR was used among disabled children and youth to reflect on their social lives, including relationships with peers, friends, and interactions with family members (Capewell, 2016; Danker et al., 2017, 2019; Feldner et al., 2019; Goodall, 2020; Ha & Whittaker, 2016; Mamaniat, 2014; Obrusnikova & Cavalier, 2011; Okyere et al., 2019; Weiss et al., 2017; Zilli et al., 2020). For instance, in Goodall’s (2020) paper, participants used the draw-and write technique and semi-structured interviews to reflect on the concept of inclusion with their peers. For them, inclusion comprised a sense of belonging as well as feeling valued. Furthermore, Mamaniat’s (2014) study revealed the centrality of the social world for disabled youth. These youth used photographs to reflect on togetherness and belonging at school and in the community. Similarly, in Okyere’s (2019) study, participants used the draw-and-write technique and participated in interviews to reflect on how experiences of inclusion were influenced by social comparisons to peers. ABR revealed the centrality of social experiences with peers, friends, and family to the wellbeing of young disabled people. In some studies, the very process of engaging in ABR emphasized the centrality of the social, as art-creation was at times, a collaborative event that involved the parents of child and youth participants. For example, in Capewell’s (2016) study, a participant’s mother created a photo-montage depicting her child’s experience with glue ear, while the study by Feldner et al. (2018) allowed children with mobility impairments and their family members to take photographs surrounding the experience of powered mobility provision.

Methodological Insights

Our narrative review revealed several methodological issues in the application of ABR with disabled children and youth.

a) Type of ABR and ABR purpose:The primary type of visual ABR was photo-based methods, such as photovoice, photo-elicitation, and photo journaling (Capewell, 2016; Danker et al., 2017, 2019; Feldner et al., 2019; Ha & Whittaker, 2016; Mamaniat, 2014; Obrusnikova & Cavalier, 2011; Weiss et al., 2017; Zilli et al., 2020). Photovoice and photo-elicitation are qualitative methods characterized by taking photographs with a camera and using the photographs to prompt discussion during interviews. Photovoice is generally thought to foster a participatory research climate (Author et al., 2017). This was followed by drawing-based methods, such as the draw-and-write technique (Goodall, 2020; Mah et al., 2020; Okyere et al., 2019). The draw-and-write technique is an arts-based method characterized by drawing an image and a short sentence in relation to a written or verbal prompt. For instance, a researcher might ask a child to please “draw your experience of disability”. Prompts by the researcher seem to be ubiquitous.

Research teams used ABR for a wide range of purposes. The vast majority of researchers undertook ABR studies because of a need to better promote collaborative and constructive engagement with children and young people using a collaborative process (Capewell, 2016; Danker et al., 2017, 2019; Goodall, 2020; Ha & Whittaker, 2016; Mah et al., 2020; Mamaniat, 2014; Obrusnikova & Cavalier, 2011; Okyere et al., 2019; Zilli et al., 2020). Other researchers used ABR in an effort to reduce barriers that young disabled people might have faced if they relied on more traditional methods, such as writing or speaking (Danker et al., 2017, 2019; Feldner et al., 2019; Ha & Whittaker, 2016; Mamaniat, 2014; Weiss et al., 2017). One research team undertook ABR in an effort to generate knowledge (Mah et al., 2020), while another employed these methods to empower participants and to reduce power imbalances between researchers and participants (Mamaniat, 2014).

b) Philosophical Orientation and Rigour:Only three research teams made mention of their philosophical and epistemological orientation (Capewell, 2016; Mah et al., 2020; Mamaniat, 2014). In contrast, nine research teams did not mention underlying philosophical orientation.

Eleven of the studies used ABR in conjunction with more traditional qualitative methods, such as interviews (Capewell, 2016; Danker et al., 2017, 2019; Feldner et al., 2019; Goodall, 2020; Ha & Whittaker, 2016; Mah et al., 2020; Mamaniat, 2014; Okyere et al., 2019; Weiss et al., 2017; Zilli et al., 2020). In this way, ABR was used as an adjunctive “add-on”. One study used ABR alongside quantitative methods (Obrusnikova & Cavalier, 2011).

c) Artistic mentorship:Nine of the studies conducted instructional training sessions on arts-based tasks to provide participants with knowledge on how to undertake ABR. For example, formal sessions on how to take photos were held with participants (Capewell, 2016; Danker et al., 2017, 2019; Feldner et al., 2019; Ha & Whittaker, 2016; Mamaniat, 2014; Obrusnikova & Cavalier, 2011; Weiss et al., 2017; Zilli et al., 2020). One study did not provide any artistic mentorship or training (Goodall, 2020). In contrast, two studies used a more balanced approach by providing participants with supportive affirmations rather than instructional learning (Mah et al., 2020; Okyere et al., 2019). The findings are discussed below in the context of the research.

Discussion and Future Directions

Disabled children and youth used ABR to illuminate the significance of educational and social issues in the context of their own lives. For instance, many children and youth engaged ABR as a way to communicate frustrations and challenges in the school environment, such as poor adaptations to curriculum or negative interactions with other students and staff. School experiences, however, were not entirely negative (Mamaniat, 2014). Although the field of education and disability is very active with a lot of recently published literature on the educational issues and challenges that disabled young people face (Underwood, Valeo, & Wood, 2012), future researchers should consider using photovoice and other ABR methods to deepen and enrich engagement with school and pedagogy as a research foci.

Relatedly, ABR also revealed the centrality of social experiences with peers, friends, and family for disabled young people. For instance, they often used ABR to reflect on feelings of belonging, worth, and inclusion with important social figures in their lives. Peers and family are known to exert a profound impact on child development with family playing a larger role in the early years and friends taking on greater significance in late childhood and adolescence (El Nokali et al., 2010). Those that work with disabled youth should be aware of the centrality of the social world and social interactions for these young people and should aim to reduce barriers to inclusion and social support.

Most of the ABR-disability studies that comprised this review were conducted with autistic children and youth. Given the social and communicative challenges associated with ASD (Müller et al., 2008), this is unsurprising. However, only a few studies explored the role and impact of ABR on young physically disabled people. In their review of the presence/absence of disability in school travel research, Author and Author (2018) noted a focus on children with cerebral palsy. We wonder, then, if perhaps there is a tendency toward matching methods and questions toward bodies that are assumed to move, interact with, and understand the world in specific ways – i.e., in research focused on school transportation and mobility, scholars might be drawn toward children and youth with mobility impairments, for example. In the case of ABR, the focus on ASD could be the result of assumptions about sensory experience and communication – and a desire to seek out approaches to enable different types of communication that are aligned with the abilities of children with ASD. Future researchers should consider widening the populations ABR is delivered to with attention to including children and youth living with physical disabilities.

Although children and youth between the ages of 4 and 18 were included in these studies, most of the articles were heavily focused on late childhood and adolescence. The use of ABR with adolescents is arguably important. That said, there was a lack of engagement with the arts in the early years with disabled children. This is problematic on many fronts. First, it is advisable for artistic exposure to begin early in life so that children and youth can form the basis of artistic participation for life (Meiners, 2005). Second, the notion that very young disabled young children are not capable of arts engagement is underpinned by powerful normative developmental scripts that promote the idea that certain capacities and stages need to be developed before arts-engagement is possible (Gabriel, 2021). The insistence for children to do things “on time” has been somewhat troubled by the new concept of “crip time” that is more attentive to how disabled bodies experience time and its passage (Katzman, Kinsella, & Polzer, 2020). Future researchers should try to employ ABR with a wider age range of children with a view to questioning and breaking down developmentalism in artistic processes.

All of these ABR studies were conducted in North America, Europe, or Australia. Countries using ABR in the Global South were not represented in our review at all, nor other published reviews of literature. Most of the articles did not report on the race or ethnicity of their participants. This is problematic on numerous fronts. There are literal and symbolic associations between the arts and Whiteness (Berger, 2005). Thus, through much of human history, European-American Whiteness has guided the form and the meaning of the visual arts. How we interpret art is also grounded in Whiteness as a lens on which the world is seen (Berger, 2005). Thus, across the arts and ABR, there is an urgent need to begin decolonizing the arts from the way visual arts are conceived of, made and created, and interpreted and displayed. Historical and recent human injustices have occurred among Black and Indigenous communities in North America. For example, more attention is being drawn toward the excessive use of police violence on black lives as well as the ancestral trauma suffered by survivors of residential schools and their families. Thus, the use of ABR to combat and address injustice is urgently needed. Future research activities must engage ABR scholars across different countries and employ approaches that de-center whiteness in the arts.

The most commonly employed visual methods were photovoice and the draw-and-write method. As cameras have become part of cell phone technology, photovoice is an increasing accessible visual method. That said, Gubrium and Harper (2016) warn that the user-friendliness and ease of photovoice can often contribute to the inaccurate usage of this method. Researchers often overlook the long-term ethnographic immersion in culture that should always accompany photovoice investigations. Other issues and problems with photovoice also exist in the literature we reviewed. For instance, the researchers did not discuss whether they were considering only literal representations of reality, rather than non-literal and symbolic meanings. Additionally, the camera experience of the participants was unknown. And, without instruction and resources, marginalized participants may be disadvantaged during photovoice. Future researchers should follow Gubrium and Harper (2016)’s guidelines and ensure that photovoice is employed correctly. Despite the importance of photovoice to fostering a participatory research climate (Author et al., 2017), researchers should consider providing participants with a wider array of meaningful visual methods, such as body-mapping and portraiture, for example.

Most of the studies employed ABR as a method alongside other more traditional methods, such as interviews. It was often unclear whether researchers were using ABR as a means to triangulate their data, or whether they were doing so to increase the trustworthiness of their findings. Indeed, the word “triangulation” was not employed in all studies that used multiple sources of data. Only four studies mentioned the term “triangulation” (Danker et al., 2019; Goodall, 2020; Ha & Whittaker, 2016; Okyere et al., 2019), while two studies explicitly expressed that they used a triangulated approach. While data triangulation is important to deepen methodological engagement, it is notable that only one study employed ABR for knowledge generation (Mah et al., 2020). The marginalization of the visual has been noted by many arts-based researchers (Seifert, 2009) as well as those in the field of arts education (Detels, 1999). Not using ABR as a tool for knowledge generation does maintain the peripheral nature of visual culture and the ascendancy and persistent domination of text-based forms of knowing. Future researchers should undertake training in visual analysis and allocate time and space for analysis of the visual within their study designs. Only three research teams declared their onto-epistemological underpinnings and how these guided their thinking and execution of ABR. This is particularly problematic and reflects a need for far greater reflexivity in the delivery of ABR studies. Situating the research team with respect to the nature of reality and knowledge is important so that readers are aware of some of the foundational assumptions guiding their work. Future researchers should try to engage reflexivity and onto-epistemology to a greater degree.

Many existing ABR studies with adults have a critical orientation (Jones & Collins, 2020). However, few of the childhood disability ABR studies and adult reviews of literature that we engaged were theoretically informed by a critical disability orientation. The lack of theoretical enrichment with a critical disability studies approach may unwittingly reproduce discourses of “art as therapy” while leaving entrenched assumptions about the arts and childhood disability intact. Using a critical disability orientation (Goodley, 2013), it is also important to ask other troubling questions such as: what constitutes an artist? What constitutes art? Do the arts encompass ableism? Do the arts contribute to the persistence of ableism? When considering the arts and disability, are the arts being used for a rehabilitative aim or for the inherent process of art-making? We encourage future researchers to adopt a critical orientation both in child ABR studies and reviews of literature.

Limitations

There are several limitations pertaining to our review as well as the literature we considered. In terms of our review, the more flexible and open-ended inclusive nature of the narrative review of literature might limit the rigour and systematic nature seen in other review types, such as scoping or systematic reviews. Further, there are also limitations in the existing literature base. The literature base on ABR and childhood disability is extremely scant with an over-reliance on photovoice and drawing methods. This limits the scope of review issues generated. Although authors labelled their studies as ABR, for us, many of them appeared to be more in the spirit of arts-informed research because more troubling questions, such as how did the children want to be seen or how did they choose to represent themselves – were not asked by researchers. Although we only searched health databases, education featured as a prominent theme in our narrative review of literature, speaking to the centrality of educational issues to the lives of these children and youth. This may speak to the overlap between health and education and the fact that education and health should not be considered as separate silos. Further, it is perhaps important to consider “health” not only in biomedical terms but also in ways that encompass social, educational, and emotional well-being as well. Indeed, health is powerfully shaped by social determinants (Raphael, 2009) such as education, income, race, and ethnicity.

Conclusion

ABR might provide disabled young people with alternative means of communication beyond the typical (and heavily relied upon) traditional text-and speech-based methods. As well, ABR departs from the long history of exposure to biomedical and rehabilitation environments that these children and youth so often experience. In this critical narrative review of the literature, we explored how disabled children and youth have utilized ABR in the context of their own lives as well as the methodological insights arising from the application of this qualitative tradition to the lives of these young people. Most of the research designs were qualitative in nature, or of mixed methodology. The most heavily employed method was photovoice, followed by drawing-based methods, such as the draw-and-write technique. Most of the studies were undertaken with older children or teenagers, with very little ABR engagement in early childhood. ABR was mostly used to promote collaborative engagement with young people or to reduce barriers to research engagement. Few studies used ABR for knowledge generation. Rather, most studies engaged ABR for data triangulation, which contributes to maintaining the peripheral status of the visual in contemporary culture. There was a lack of theoretical engagement with critical disability approaches, which risks leaving unquestioned, but problematic assumptions about the arts and childhood disability intact.

Disabled children and youth used ABR to reflect upon their educational experiences, as well as the relevance of the social world to their lives as children with disabilities. ABR can be used to reflect upon and communicate social and personal issues in the lives of young people with disabilities as well as to promote deeper engagement in the research process through improved communication. Future researchers should consider engaging a wider age range of children and youth, departing from Euro-centric notions of what art is, widening the repertoire of visual methods to include other approaches, and carefully engaging in visual ABR for knowledge generation rather than data triangulation to avoid contributing to the maintenance of the peripheral status of the visual in research. Lastly, researchers should be encouraged to engage critical disability approaches that critique normative assumptions about the arts and childhood disability. When disabled children and youth are behind the paintbrush as artistic agents in ABR, it is clear that there is much to learn.

Declaration of Confliction Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada - Insight Grant, in 2020 (SSHRC-IG).

References

- Allen, A. (2019). Intersecting Arts Based Research and Disability Studies: Suggestions for art education curriculum centered on disability identity development. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 34(1).

- Barron, B. A. (2016). Gibson, B. E.: Rehabilitation: A post-critical approach. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 26(3), 392–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-016-9649-y

- Berger, M. A. (2005). Sight unseen: whiteness and American visual culture. University of California Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utoronto/detail.action?docID=239227

- Botha, M., Hanlon, J., & Williams, G. L. (2021). Does language matter? Identity-first versus person-first language use in Autism research: A response to Vivanti. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04858-w

- Boydell, K. M., Gladstone, B. M., Volpe, T., Allemang, B., & Stasiulis, E. (2012). The production and dissemination of knowledge: A scoping review of arts-based health research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1711

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Capewell, C. (2016). Glue ear – a common but complicated childhood condition. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 16(2), 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12100

- Culley, L., Law, C., Hudson, N., Denny, E., Mitchell, H., Baumgarten, M., & Raine-Fenning, N. (2013). The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: A critical narrative review. Human Reproduction Update, 19(6), 625–639. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt027

- Danker, J., Strnadová, I., & Cumming, T. M. (2017). Engaging students with Autism Spectrum Disorder in research through participant-driven photo-elicitation research technique*. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 41(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2016.7

- Danker, J., Strnadová, I., & Cumming, T. M. (2019). Picture my well-being: Listening to the voices of students with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 89, 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.04.005

- Detels, C. (1999). Hard boundaries and the marginalization of the arts in American education. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 7(1), 19–30.

- Driessnack, M., & Furukawa, R. (2012). Arts-based data collection techniques used in child research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing: JSPN, 17(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6155.2011.00304.x

- El Nokali, N. E., Bachman, H. J., & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2010). Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school. Child Development, 81(3), 988–1005. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01447.x

- Feldner, H. A., Logan, S. W., & Galloway, J. C. (2019). Mobility in pictures: A participatory photovoice narrative study exploring powered mobility provision for children and families. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology, 14(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2018.1447606

- Fraser, K. D., & al Sayah, F. (2011). Arts-based methods in health research: A systematic review of the literature. Arts & Health, 3(2), 110–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2011.561357

- Gabriel, N. (2021). Beyond ‘developmentalism’: A relational and embodied approach to young children’s development. Children & Society, 35(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12381

- Gastaldo, D., Rivas-Quarneti, N., & Magalhaes, L. (2018). Body-map storytelling as a health research methodology: Blurred lines creating clear pictures. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.2.2858

- Gibson, B. (2016). Rehabilitation: A post critical approach. Taylor and Francis. New York.

- Giles, M., Curran, CJ., Crossman, S., & Moola, F. (2020). Fostering belonging through the arts for children and youth with disabilities: The power of a community-based arts program in Ontario, Canada . The International Journal of Social, Political and Community Agendas in the Arts , 15 (3), 15-26. doi:10.18848/2326-9960/CGP/v15i03/15-26.

- Goodall, C. (2020). Inclusion is a feeling, not a place: A qualitative study exploring autistic young people’s conceptualisations of inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(12), 1285–1310. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1523475

- Dan Goodley (2013) Dis/entangling critical disability studies, Disability & Society, 28:5, 631-644, DOI: 10.1080/09687599.2012.717884 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.717884

- Douglas, P., Rice, C., & Siddiqui, A. (2020). Living dis/artfully with and in illness. Journal of Medical Humanities, 1-16.

- Eales, L., & Peers, D. (2016). Moving adapted physical activity: The possibilities of arts-based research. Quest, 68(1), 55-68.

- Gubrium, A., & Harper, K. (2016). Participatory visual and digital methods. Routledge. London.

- Ha, V. S., & Whittaker, A. (2016). ‘Closer to my world’: Children with autism spectrum disorder tell their stories through photovoice. Global Public Health, 11(5–6), 546–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1165721

- Holochwost SJ., Goldstein TR., & Wolf DP. (2021) Delineating the benefits of arts education for children's socioemotional development. Frontiers of Psychology, 12, 624712. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.624712

- Imrie, R. (2004). Disability, embodiment and the meaning of the home. Housing Studies, 19(5), 745–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267303042000249189

- Jensen, K. B. (1991). Introduction: The qualitative turn. In A Handbook of Qualitative Methodologies for Mass Communication Research. Routledge.

- Jones, C. T., & Collins, K. (2020). Ordinary Extraordinary Activism: Student-led filmmaking in disability studies. International Journal of Education through Art, 16(1), 29-41

- Katzman, E., Kinsella, E., & Polzer, J. (2020). Everything is down to the minute: clock time, crip time and the relational work of self managing attendant services.

- Julie K Krøier, PhD Fellow, Brynjulf Stige, PhD, Hanne Mette Ridder, PhD, Non-Verbal Interactions Between Music Therapists and Persons with Dementia. A Qualitative Phenomenological and Arts-Based Inquiry, Music Therapy Perspectives, Volume 39, Issue 2, Fall 2021, Pages 162–171, https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/miab008

- Law, M., Petrenchik, T., King, G., & Hurley, P. (2007). Perceived environmental barriers to recreational, community, and school participation for children and youth with physical disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(12), 1636–1642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.035

- Mah, K., Gladstone, B., King, G., Reed, N., & Hartman, L. R. (2020). Researching experiences of childhood brain injury: Co-constructing knowledge with children through arts-based research methods. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(20), 2967–2976. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1574916

- Mamaniat, I. (2014). Listening to children in an English special school: Photo journals and the dilemmas of analysis. In Photography in Educational Research. Routledge.

- Meiners, J. (2005). In the beginning: Young children and arts education. International Journal of Early Childhood, 37, 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03165744

- Müller, E., Schuler, A., & Yates, G. B. (2008). Social challenges and supports from the perspective of individuals with Asperger syndrome and other autism spectrum disabilities. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 12(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361307086664

- Mykitiuk, R., Chaplick, A., & Rice, C. (2015). Beyond normative ethics: Ethics of arts-based disability research. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, 1(3), 373-382.

- Obrusnikova, I., & Cavalier, A. (2011). Perceived barriers and facilitators of participation in after-school physical activity by children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 23, 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-010-9215-z

- O’Donoghue, D. (2009). Are We asking the wrong questions in arts-based research? Studies in Art Education, 50(4), 352–368.

- Okyere, C., Aldersey, H. M., & Lysaght, R. (2019). The experiences of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in inclusive schools in Accra, Ghana. African Journal of Disability, 8, 542. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v8i0.542

- Oliver, M. (2013). The social model of disability: Thirty years on. Disability & Society, 28(7), 1024–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.818773

- Penketh, C. (2017). ‘Children see before they speak’: An exploration of ableism in art education. Disability & Society,32(1), 110–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2016.1270819

- Polat, B. Art education: An overview. Lyon, 2021

- Potash, J. (2019). Arts-based research in art therapy. In D. Betts and S. Deaver. Art therapy research: a practical guide. Routledge (p,

- Raphael, D. (2009). Social determinants of health. Canadian perspectives. 2nd Edition. Canadian Scholars Press Inc. Toronto.

- Rice, C., LaMarre, A., & Mykitiuk, R. (2018). Cripping the ethics of disability arts research. In The Palgrave Handbook of Ethics in Critical Research (pp. 257-272). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

- Rolling, J.H. (2010). A paradigm analysis of arts-based resaerxh and implications for education. Studies in Art Education: A Journal of Issues and Research, 51, 2, 102-114.

- Author & Author. (2018). A systematic review of disability’s treatment in the active school travel and children’s independent mobility literatures. Transport Reviews, 38(3), 349–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2017.1340358

- Seifert, L. S. (2009). Mainstreaming arts-based research: ABR’s release from marginalization. 54(1), No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014710

- Visse, M., Hansen, F., & Leget, C. (2019). The Unsayable in Arts-Based Research: On the Praxis of Life Itself. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1609406919851392

- Underwood, K., Valeo, A., & Wood, R. (2012). Understanding Inclusive Early Childhood Education: A Capability Approach. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2304/ciec.2012.13.4.290

- Weiss, J. A., Burnham Riosa, P., Robinson, S., Ryan, S., Tint, A., Viecili, M., MacMullin, J. A., & Shine, R. (2017). Understanding special olympics experiences from the athlete perspectives using photo-elicitation: A qualitative study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 30(5), 936–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12287

- Wexler, A. (2009). Art and Disability—The Social and Political Struggles Facing Education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wexler, A. (2016). Re-imagining inclusion/exclusion: Unpacking assumptions and contradictions in arts and special education from a critical disability studies perspective. Journal of Social Theory in Art Education, 36(1). https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jstae/vol36/iss1/5

- Author., Zurba, M., & Tennent, P. (2017). Worth a thousand words? Advantages, challenges and opportunities in working with photovoice as a qualitative research method with youth and their families. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2659

- Zilli, C., Parsons, S., & Kovshoff, H. (2020). Keys to engagement: A case study exploring the participation of autistic pupils in educational decision-making at school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 770–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12331