Museum as a Mutual Learning Space for Artists with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and University Students

Le musée comme espace d’apprentissage mutuel pour les artistes ayant une déficience intellectuelle et développementale et les étudiant·es universitaires

Yumi Shirai, Ph.D.

Assistant Professors

Sonoran Center for Excellence in Disabilities, Department of Family & Community Medicine

Applied Intercultural Arts Research, Graduate Interdisciplinary Program

University of Arizona

yumish [at] arizona [dot] edu

Carissa Maria DiCindio, Ph.D.

Assistant Professors

Department of Art & Visual Culture Education

Applied Intercultural Arts Research, Graduate Interdisciplinary Program

University of Arizona

cdicindio [at] arizona [dot] edu

Abstract

Using a university museum as a mutual learning space, guided by the core principles of multivocality and inclusive arts practice, six adult artists with intellectual disability and 16 undergraduate students collaborated to plan a public art exhibition. In this article, we describe the facilitation of the 6-week group process with artists with intellectual disability who have varied cognitive and communication abilities, to curate their own stories and prepare for a public art exhibition, and students to gain field experiences as community art educators, working with a community artist group. By using the expressive arts as a core communicative tool, artists with intellectual disability led small group conversations about a shared life topic of grief with university undergraduate students. In return, the students facilitated the curating process for the artists with intellectual disability, being able to transform their personal bereavement stories into a public exhibition. Evaluation of artefacts, observations and survey data demonstrated significant and positive influence on artists to synthesize their detailed stories in their works of art through creative and art-based group dialogues, and students’ skills to facilitate multivocality of practice. The results also confirmed that, with shared values of respecting diverse voices of people, creativity and reflectivity, multivocality and inclusive arts practice are compatible frameworks for setting up an inclusive community project.

Résumé

En utilisant un musée universitaire comme espace d’apprentissage mutuel, guidé par les principes fondamentaux de la multivocalité et de la pratique artistique inclusive, six artistes adultes ayant une déficience intellectuelle et 16 étudiants de premier cycle ont collaboré pour organiser une exposition d’art publique. Dans cet article, nous décrivons la facilitation du processus de six semaines d’un groupe composé d’artistes ayant une déficience intellectuelle dont les capacités cognitives et de communication étaient variées et qui devaient organiser leurs propres histoires et se préparer pour une exposition d’art public, et d’étudiant·es qui devaient acquérir de l’expérience de terrain en éducation artistique travaillant avec un groupe d’artistes de la communauté. En utilisant les arts d’expression comme outil de communication de base, les artistes ayant une déficience intellectuelle ont mené des conversations en petits groupes dont le sujet de vie partagé était le deuil avec des étudiant·es au premier cycle. En retour, les étudiant·es ont facilité le processus de conservation pour les artistes ayant une déficience intellectuelle, visant à transformer leurs histoires personnelles de deuil en une exposition publique. L’évaluation des artéfacts, des observations et des données de sondage a démontré une influence significative et positive sur les artistes pour synthétiser leurs histoires détaillées dans leurs œuvres d’art par le biais de dialogues de groupe créatifs et basés sur l’art, et les compétences des étudiant·es pour faciliter la multivocalité de la pratique. Les résultats ont également confirmé qu’en partageant des valeurs de respect de la diversité des voix, de créativité et de réflexivité, la multivocalité et la pratique artistique inclusive sont des cadres compatibles pour la création d’un projet communautaire inclusif.

Keywords: Intellectual Disability; Museum Education; Inclusive Arts Practice; Multivocality; Grief

Introduction

Using a university museum as a mutual learning space, guided by the core principles of multivocality (Pegno & Farrar, 2017) and inclusive arts practice (Fox & Macpherson, 2015), six adult artists with intellectual disability and 16 undergraduate students collaborated to plan a public art exhibition. By using the expressive arts as a core communicative tool, artists with intellectual disability led small group conversations about a shared life topic of grief with university undergraduate students. In return, the students facilitated the curating process for the artists with intellectual disability, being able to transform their personal bereavement stories into a public exhibition.

Through this collaborative process, the feelings surrounding loss were given a voice through the works of art the artists with intellectual disability created and the stories and ideas they shared with students in the exhibit labels. Imagination also shows us where work should continue to create inclusive art museum spaces by considering whose voices are left out. As Harwood (2010) noted, “imagination not only enables us to appreciate the plurality of the world, it is invaluable in supporting the ongoing task of identifying exclusion: in the world, in our own assumptions and, importantly, in art itself” (p. 366).

In this article, we describe the group facilitation process and provide the evaluation results for 1) artists with intellectual disability who have varied cognitive and communication abilities, to curate their own stories and prepare for a public art exhibition, and 2) students to gain field experiences as community art educators, working with a community artist group.

University Art Museums as Sites for Community Dialogue

University art museums have the potential to serve as bridges between universities and communities as sites where people can come together to share ideas, experiences, and emotions through interactions with each other and works of art. Community exhibitions in museums, in particular, by providing “safe and critical context,” provide opportunities for community groups to share collective ideas and concerns to a broader community which foster “empathy through experiential learning, storytelling, artistic expression, dialogue and contemplation” (Gokcigdem, 2016, p. xxi). This interaction among different groups provides further opportunities to identify common threads and promote understanding.

Multivocality. This type of community engagement through university galleries is supported by actively creating collaborations focused on “Multivocality,” that is, emphasizing multiple perspectives that are “participant-directed” rather than interpreted by museum staff (Pegno & Farrar, 2017, p. 170). By asking community members to speak for themselves as art exhibitors in the galleries, museum practitioners create collaborations “built on relationships” (Pegno & Farrar, 2017, p. 180). These relationships develop through repeated interactions between museum staff and community artists as they plan the exhibition together, a commitment that takes time to build trust and understanding. Community exhibitions in university art museums connect these sometimes siloed institutions with neighbors outside of campus, and the perspectives offered in these galleries give university students opportunities to connect to community members through interactions with each other and works of art.

Collaborative, Inclusive Arts Practice with People with Intellectual Disabilities. To facilitate a successful inclusive creative collaboration with people with intellectual disability, who have varied cognitive and communication skills, it is important to recognize necessary preparations and parameters (Fox & Macpherson, 2015). According to Fox and Macpherson (2015), “Inclusive Arts” is defined as a mutually beneficial, creative collaboration between people with and without intellectual disability where all artists involved in the process can learn and unlearn from each other. In this mutual creative process, the inclusive arts first views people with intellectual disability as unique contributors of collaborative processes and creations, unlike other deficits/needs-based practices, such as art therapy and participatory action research, which are typically originated to address specific issues and challenges.

By using “aesthetic of exchange” as the center of creative collaboration, people with intellectual disability play valuable and skillful contributors for reimagining how arts and society, including the current life topic of grief, “might be” beyond traditional forms and representations (Fox & Macpherson, 2015, p2). To achieve a successful aesthetic exchange practice, Fox and Macpherson (2015) laid out key elements which include providing frameworks and foundations as starting points, taking a group journey with an open mind, securing plenty of time, having choices and freedom, being patient, developing a trusting relationship, being open to all forms of communication/expression, being reflective, and seeking answers in the participants. By providing proper materials and space for in-depth exchange through skilled facilitation, the inclusive arts may also produce high quality arts with unique concepts and frameworks which may contribute to a broader audience.

A Museum Community Art Exhibition on Loss and Grief by Artists with Intellectual Disability. Grief is a universal life challenge for all human beings, but for people with intellectual disability, there are exacerbated challenges. As life expectancy of adults with intellectual disability approaches that of the general population, most individuals with intellectual disability outlive their parent-caregivers, causing them to face multi-layered losses, such as their life-long primary caregiver, residence, familiar daily routine, and social network (e.g., Clute, 2010; Doka, 2010; Young et al., 2017). The extant literature supports that by engaging in learning opportunities with emotional support, most individuals with intellectual disability can navigate functional and adaptive grieving (Lavin, 1989). However, misconceptions about the capacity of people with intellectual disability to understand and process their grief, disenfranchise their grief experiences and support needs (e.g., Clute, 2010; Doka, 2010; Lavin, 1989).

To raise public awareness concerning these issues, six adult artists with intellectual disability and 16 undergraduate students collaborated to plan a public art exhibition at a university museum. The university students came into this collaboration with fundamental knowledge to facilitate multivocality practice, as museum educators from their community art education course, whereas the artists with intellectual disability came into this collaboration with lived experiences of grief and loss, and foundational concepts of grief and death through their prior 10-week, art-based grief workshops guided by a grief counselor. These separate prior trainings/experiences provided a foundation for this collaboration project, which was a necessary first step to setting an inclusive arts project (Fox & Macpherson, 2015).

Current Study

The current study examined how this museum-based, multi-group project with community artists with intellectual disability and university students from an art education course provided mutual learning opportunities for both groups. Our specific research questions included:

- Whether and how the small group structured dialogue sessions with museum support staff (university students) are an effective format to assist artists with intellectual disability to curate their stories for a public exhibition.

- Whether and how the small group structured dialogue sessions with artists with intellectual disability are an effective format for museum support staff (university students) to facilitate the multivocality practice.

Methods

Participants

Artists with Intellectual disability.. Six adults with intellectual disability from a community art studio who have experienced the death of a close family member and completed a 10-week expressive arts-based grief support workshop, were invited to join this exhibition. Through the grief support group, these artists had opportunities to reflect and process upon their loss-related experiences and feelings through varied expressive activities, and voluntarily expressed their wish to take part in the public exhibition. Although these artists became familiar with the concepts of grief and comfortable with sharing their loss-related experiences via support group sessions, they had not yet had opportunities to share stories and memories of loved ones.

At the enrollment of the 10-week expressive-arts based grief support group, artists, ages 35 to 42 years from a community art studio for adults with intellectual disability, were informed of an optional opportunity to participate in a public art exhibit. The participation criteria for the grief support group included adults with intellectual disability who 1) had personal loss experience with a close person (e.g., a family member, a caregiver) more than six months prior, 2) were comfortable with using art media, 3) were willing to participate in a group grief process, and 4) did not require individualized counseling/therapy. At the end of the 10-week session, all six participants were interested in being part of the public art exhibit component.

Undergraduate Students Enrolled in an Art Education Course. The undergraduate students were recruited from an upper-level art education course with an emphasis on art museum education. Additionally, this class is offered as an elective for undergraduates at the university; about half of the students were enrolled in art or art education, and the other half came from a diverse range of programs including business administration, engineering, and agriculture. Students were given the option to participate in this study, but all participated in the class activities that were part of this project.

Prior to this project, the university students in this course focused on ways to open art museums to wider audiences through programming and exhibitions. They learned about the concept of multivocality (Pegno & Farrar, 2017) and roles of community exhibitions in relation to community participants, audiences, and learning. They also learned how language and style could help communicate ideas to visitors reading the labels of the art pieces in the galleries.

In a six-week group process, the students’ roles as community art facilitators were to provide support and guidance to the artists to develop strategies and plans to transfer their voices into synthesized works of art ready for gallery display. This project offered students first-hand, experimental learning opportunities as to how their university art museum works with a community group (artists with intellectual disability) with whom they may not typically be connected through in social interactions (Kolb, 2014).

The study related procedures and documents were approved by the University Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects. We obtained media releases from artists for all images that were used in this manuscript.

6-Week Group Process

Over 6 weeks, the sixteen students and the 6 artists with intellectual disability were assigned into 5 working groups; each group consisted of 3-4 undergraduate students with 1-2 artist(s) who worked together weekly for 45 minutes. Each group was provided weekly instruction with specific goals and activities with flexibility to collaboratively achieve objectives so each group could independently facilitate and carry conversations and activities. The project objectives were to: a) curate specifics of grief-related stories that the participant wanted to share at the public art exhibit, b) select the exhibition format (e.g., painting, comic strip, book), and c) draft labels as supplemental exhibit material that best supported the wishes of the artists. The detailed structured group activities were described in Table 1.

| Week 1: Getting to know you |

|---|

| Objective: Each group member to understand and learn about the other group members and the unique communication styles of the focused artists with intellectual disability an aspect that continued each week as students and artists collaborated together. Activities: Each group was given multiple sheets of paper with activity instructions and basic art supplies, such as crayons and markers, so not only the students, but also the focused artists with intellectual disability could freely share and document their discussion despite their varied literacy skills. After initial introductions, including sharing the members’ backgrounds, names, and hometowns, the groups worked on an ice breaker activity in which they discussed and documented members’ ideal vacations. |

| Week 2: General thoughts on "loss, grief and spirituality" and a selection of exhibit topic |

| Objective: Student members to understand the focused artist’s exhibit topic of “about whom and/or what” they would like to create their works of art Activities: Group discussed the general thoughts and experiences on loss, grief and spirituality by sharing group members’ grief related stories. The students were also encouraged to share their thoughts and experiences related to the topic. |

| Week 3: Personal story sharing |

| Objective: Gather detailed information about the focused individuals’ stories as they related to the exhibit topic. Activities: Students were given several prompt questions as examples to start conversations: 1) What is his/her favorite memory with [the loved one]? 2) What is the place that reminds him/her of [the loved one or God/spirituality]? 3) Does he/she remember places where he/she went with [the loved one]? 4) What is his/her favorite holiday/vacation related to the memories of [the loved one]? 5) What does he/she miss the most about [the loved one]? 6) How/When do you talk to [the loved one or God]? 7) What do you do to remember [the loved one]? 8) What did [the loved one or God/Spirituality] mean to him/her? 9) What do you do to be connected with [the loved one or God/Spirituality]? As the focused artists shared their stories, the students were also encouraged to share their thoughts and experiences. The student group members documented notes from the conversations on the papers. |

| Week 4: Story and exhibit format selection |

| Objective: Develop the focused artists’ visions for their works of art with precise stories and formats. Activities: Group discussed the prompt question “What do you want people who come to the art show to know about [the loved one or God/spirituality]? Select three things.” After the artists selected a few stories, the groups worked together on further discussing, remembering and documenting key detailed elements of the stories. Based on the refined stories, students worked with the artists to explore and decide on the format and materials they wanted to use to depict their stories for the art exhibit. |

| Week 5: Developing label supplemental information |

| Objective: Develop exhibit labels as supplemental exhibit material. Activities: Before students were separated into the groups for the class, we reviewed and discussed the purpose of the label, which is to provide supplemental information for the audience to understand and interpret the exhibited works of art. We also emphasized that the background story should be told from the artists’ perspectives. Each group developed a draft of the label, first clarifying people, objects, context, and/or activities in the picture. Additionally, each group further discussed the reasons why the artist chose their story. |

| Week 6: Group presentation |

| Objective: Reviewing, summarizing, and sharing each group process, outcomes and reflections. Activities: We ended the sessions with group presentations of summaries from each group, including the process, discussions, and decisions regarding the art show. Prior to the presentation day, university students gathered all the materials from the past five weeks and developed PowerPoint presentations without the focused individuals. On the presentation day, students and the artists in each group stood by their slides and took turns describing their group process and outcomes to the entire class. |

Evaluation Procedure

The director of the community art studio and the instructor of the community art course, where the study participants were recruited from, conducted data collection and analyses. We planned and coordinated the overall project, but we participated in the small group activities, as observers, instead of guiding the small group process, to take notes, gather and preserve both qualitative and quantitative data described in below sections.

Artists.To evaluate the impact of the project on artists, we took an ethnographical approach to carefully observe and document the six-week group process by taking notes on key comments and behaviours made by artists, support staff, and students, and preserving artifacts produced, such as instruction for group activities, group notes, products, and presentations. The qualitative data were reviewed to see whether and how the group process achieved the project objectives for the artists to curate grief-related stories for the public exhibition. The ethnographical data collection and analysis approach was selected not only for the appropriateness of describing the group process, but also to gather a broader spectrum of data with the given, potential disadvantage of artists with intellectual disability through written and spoken language. Based on observable and documented data related to the process and visual products, we evaluated how artists actually participated in the dialogues and interactions through visual arts and other modes of expressive communication, how each group documented these exchanges, and how this information was synthesized in their art plans, final works of art, and their supplemental documents.

Students. To evaluate the impact of the group project on students, pre- and post-group project evaluation surveys and project reflection notes were employed. As the purpose of student evaluation was to examine the changes in student skills in facilitating the multivocality practice with a group of people with intellectual disability, we asked student participants questions regarding their perceptions about the project topic of death and dying as well as the capacity of people with intellectual disability in understanding the concept of and dealing with death and dying. To capture the project impact, these questions were asked via surveys prior to and after the project. We also included open-ended survey questions and student reflection notes as supplemental qualitative data to provide additional insights to interpret quantitative survey analysis results as well as to describe group processes and to capture related key themes.

Student Surveys. Pre- and post-project surveys with Likert scales and open-ended questions were implemented. In the survey, the students were asked to report their level of comfort in talking and sharing their thoughts about life and death, and their perception of the capacity of individuals with intellectual disability to understand and process grief. For each item on a 4-point scale, students indicated their level of comfort, ranging from 1 (very uncomfortable) to 4 (very comfortable); and their perceptions, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a lot). In open-ended questions, students were asked to elaborate their thoughts on the survey topics.

Student Reflections. Right after each group activity, in a separate classroom with the course instructor, students had opportunities to share their thoughts about their experiences, working with the artists in their groups. At the end of the project, students were asked to document and submit their reflective thoughts. Please see reflection prompts in Table 2.

|

Student Outcome Analsyses Strategies. To evaluate changes in students’ perceptions, we conducted a series of Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, comparing pre- and post- survey scores by using a statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics—version 26). To gather nuanced information, we conducted a content analysis on open-ended questions and reflection notes (Assarroudi et al., 2018). Two researchers independently read and re-read the qualitative documents to identify key contents that captured meaningful changes and the impact from the group activities on the students’ perceptions.

Results

Artists

The qualitative analysis results of 6 artists’ qualitative data revealed a few key themes that are related to artists’ growth in story-curating, and art-making processes and products. The below listed qualitative results support that the small group, guided by weekly objectives and activities (see Table 1), provided a feasible and effective format for artists to curate their personal grief related stories for a public exhibition.

Facilitation of Self-Curating Process In a typical studio practice for a public exhibition, the artists take about one week to select a topic/theme and develop details of individual stories and art plans in a large group setting. For this grief exhibition, they spent a longer period (six weeks) to curate their stories and decide on their art media and formats in a smaller, structured group setting via in-depth dialogues. See Table 1 for weekly activities and short example questions. As a result, this group process expanded the artists’ capacity to curate eclectic pieces of stories into synthesized plans with much more detailed elements for their arts. We identified several key success factors for the small group facilitation:

Conversational Tips. Sharing experiences, one topic at a time, over several weeks helped articulate important and detailed elements of their stories via

- Facilitating conversations with a few familiar words and casual drawings on paper

- Providing opportunities to identify additional shared topics/experiences through other participants’ related stories, including students’

- Encouraging assistive materials from home, such as photocopies (e.g., a person, camper, cabin) to share more detailed and accurate information

- Encouraging to find and practice words that are related to grief-related events and experiences with support from program staff and family members

These factors also encouraged artists to lead conversations rather than taking on the role of a passive listener. The artists recognized that their ideas/stories were the central focus of their group activities that triggered expanded, serious, and in-depth dialogues even though the initial expressed words or drawings were possibly limited (simplified or partial). We also observed as the week progressed, artists gained confidence in initiating conversations and sharing their ideas without waiting for additional support or prompts from the students.

Key Roles of Group Support. . Having consistent and attentive groups with the same students over several weeks provided artists the necessary tools to develop a synthesized, visualized map with full information for their public art piece. By understanding mutual communication styles of members, each group provided:

- A comfortable environment to share their ideas and stories, often through gestures and drawings

- Appropriate prompts or alternatives when they could not find words

- Support to document details of artists’ stories in weekly group conversation

- Support to remind key elements of stories when artists failed to recall elements in their story curating process

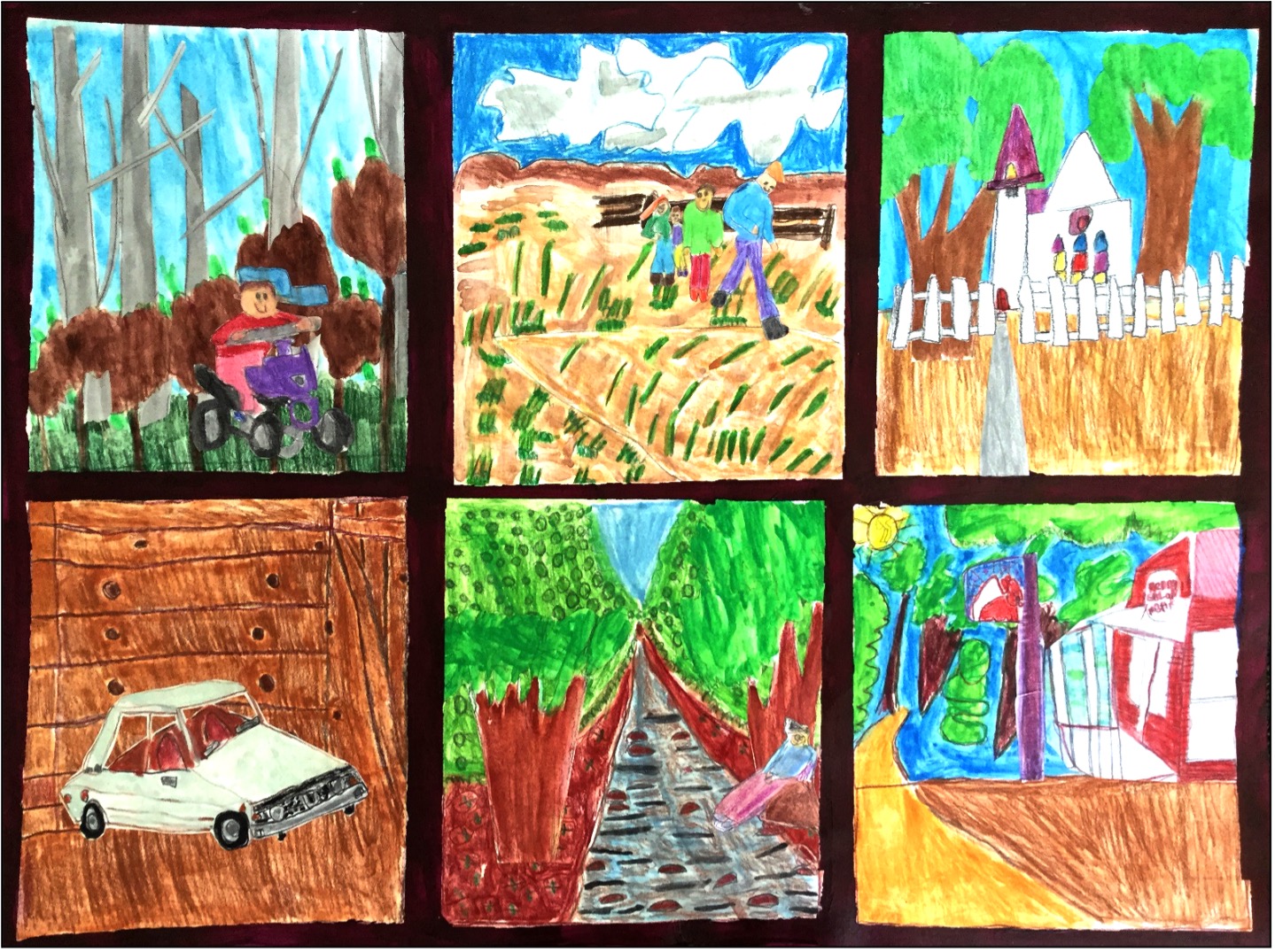

Growth in Art Practice and Final Works of Art. The self-curating grief story process in a small group setting encouraged artists’ growth in their studio practice and was reflected in their final works of art that were comprehensive and captured details of individual stories about them and their relationships with their relatives. Based on their work plans and drafted labels, the artists completed the works of art back in their community art studio. As the art studio facilitators, we observed that, compared to their previous art exhibitions, the artists had greater patience and determination in working on this particular public exhibition.

The artists seemed to put extra effort in practicing their drawing skills with many draft drawings and layering their works one step at a time for a long period. Please see examples of drafted and finalized works of art in Appendix, excerpts from labels:

To make this piece, I used pictures of my family to practice drawing everyone to capture the way they look and to have accurate details. I drew each person’s hands at least 3 times, about 30 hands! (Joey Aschenbrenner for Camping with Dad).

I worked on each box separately and blocked all the other ones so I could focus on each memory and get the details right. I decided to make this piece more realistic so I practiced on separate paper before I worked on the final piece. I am glad I chose this process because I learned new principles of art, like perspective and proportion. (Jack McHugh for Trip to Grandpa’s)

The artists took about three months to complete their final works of art, as compared to a few weeks for their typical work time.

Students

All students (N = 16) were eligible to participate. Of those 16 students, 13 (81%) voluntarily completed pre-project and 14 (88%) completed post-project surveys, and five (31%) provided permission to review their reflection notes. Students’ outcomes were examined via quantitative analyses of survey data, presented in Table 3, and content analyses on open-ended survey questions and project reflection notes. These results together revealed a few key themes.

| Pre-project | Post-project | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | Z | r | |

| Talking about death | ||||

| Range [0-4] | Range [0-4] | |||

| In general | 3.35 (.47) | 3.60 (.52) | -1.63 | -.37 |

| Regarding people they know | 3.35 (.47) | 3.55 (.50) | -1.41 | 1.32 |

| Of own | 3.15 (.58) | 3.50 (.71) | -1.44 | -.32 |

| Perceptions on capacity of individuals with intellectual disability | ||||

| Range [1-3] | Range [1-3] | |||

| Understand the terminality of death | 2.15 (.53) | 2.50 (.71) | -2.07* | -.46 |

| Experience grief | 2.35 (.47) | 2.65 (.47) | -1.73+ | -.39 |

| Articulate experiences and feelings | 1.80 (.59) | 2.35 (.82) | -2.12* | -.48 |

| Processing and coping with grief | 1.83 (.61) | 2.33 (.71) | -2.12* | -.47 |

| Adjust life without deceased | 2.20 (.35) | 2.50 (.71) | -1.30 | -.29 |

Having a Conversation about Death and Loss.In pre-workshop surveys, more than 90 % of students reported that they were somewhat to very comfortable, talking about death, prior to the project activities (see Table 3). However, qualitative content analysis with open-ended questions and reflection notes revealed some insights regarding the challenges of having conversations on the sensitive topic of grief with the artists, indicating that developing trusting relationships for facilitating group dialogue took commitment and effort from all participants. Based on weekly objectives, group members collaboratively explored different ways to share their thoughts and experiences, and by doing so, they became comfortable talking about death and dying, and familiar with the artists’ communication styles over time. The 6-week, structured instructions with simple but clear objectives and creative activities (see Table 1) provided a feasible format for the group to develop a cohesive environment. We identified several themes related to the small group conversation via qualitative analysis:

Being Uncomfortable Talking about a Sensitive Topic with Artists. In the beginning, some students indicated that they were nervous about jumping into this project and working with artists with intellectual disability with whom they had never had close interaction with before, while others were concerned about working with them on the sensitive topic of grief. For example, “I was admittedly a little nervous when we first began working with [the Community Art Studio], mostly because I wasn’t exactly sure what to expect” (Student 15). Some expressed a fear of upsetting them on the topic: “I did not want to say the wrong thing and just have them be sad.” (Student 11).

Taking Time and Making a Conscious Effort to Have Artists be Comfortable with TalkingMany reported that it took some time and effort for their artists to get comfortable and open up to them to talk about the topic: “I was previously concerned with having communication issues, or I was afraid they may not want to participate. But everything took time and effort… actively listening and trying to understand his story-telling” (Student 10); and “He was so shy but now he was showing me pictures and videos of his family and I feel like he wouldn’t do that to just anyone…” (Student 9). They were also challenged by a sensitive balance between encouraging them to talk and not providing leading questions; and “I didn’t want to say too much about any one thing. I wanted her [artist] to share what she wanted. That way she was in full control and felt confident” (Student 7).

Skills to Communicate with ArtsitsThe students reported that through their 6-week group interactions, they got to know the artists well and their unique communication styles and gained skills to better engage them to communicate their thoughts and stories: “I had never worked with artists with intellectual disability in the past and so I feel that my greatest success was getting to know the artist, and having him feel comfortable in communicating with me.” (Student 10). Some reported specific strategies. For instance, instead of asking abstract concepts, they focused on individuals’ specific memories with their families at their level of understanding: “Asking questions that the artist had the skills to answer was important...” (Student 10). Many developed their personal connections through art making: “after getting to know my artists, I found it to be a very positive and successful endeavour, especially in helping both the artists and myself make personal connections through art.” (Student 15).

They provided repeated questions and/or layered opportunities so the artists could fully understand, reflect and process the questions; this provided opportunities for the focused artist to share their thoughts and provide details and significance in their stories: “My favorite part was seeing the artist reveal more memories/details about his mom during the final presentation that he didn’t previously mention in our meeting.” (Student 3). As their artists often provided pieces of information and stories one at a time, the students, as a group, collaborated with the artists to put these pieces together to craft broader and fuller stories: “I enjoyed the label writing process because I’m a wordy person, but he is quiet. It was nice to put into words a paragraph of all the small details he shared over time.” (Student 10)

Capacity of Artists to Understand and Process Grief, and Communicate Their Perspectives.Wilcoxon signed-rank test results, comparing students’ pre- and post-project scores, demonstrated significant increases in mean scores of three items on students’ perceptions about persons with intellectual disabilities: “understanding the terminality of death”, from 2.15 (SD = .53) at pre-project and to 2.50 (SD = .71) at post-project, Z = -2.07, p < .05, with a medium effect size, r = -.46; “ability to articulate loss-related experiences and feelings”, from 1.8 (SD = .59) at pre-project to 2.4 (SD = .82) at post-project, Z = -2.12, p < .05, with a medium effect size, r = -.47; “ability to process and cope with grief”, from 1.8 (SD = .61) at pre-project to 2.3 (SD = .71) at post-project, Z = -2.12, p < .05, with a large effect size, r = -.50. The results indicate that this field experience positively influenced students’ attitudes towards the capacities of artists with intellectual disability regarding their understanding of death, and processing their loss and grief.

Qualitative analysis results provided additional insights to how students realized that the artists with intellectual disability had the capacity to understand the concept of, and emotional response to the death of a loved one. They also recognized that the artists had unique and individualized understandings, processing, and responses: “This experience impacted how I think about people with intellectual disability by showing how large of a spectrum it is and how unique and different these individuals are.” (Student 10).

Drawings and other non-verbal expressions provided significant bridges for the artists to communicate their stories, needs, and wants with confidence: “We would draw together when we couldn’t express our thoughts with words.” (Student 2); and “how they were able to express themselves so well through art.” (Student 12). The unique expressions also allowed them to realize the transformative application of arts as communicative and processing tools: “I hope that the artists got something as positive out of the experience as I did, … it is okay to experience these emotions and talk about them and work through them in the amazing way they are doing with their art” (Student 15).

Impacting Personal Perception of Death and Grief. In the class discussions and reflection notes, the topic of happiness in memories came up repeatedly as students realized they were learning about varied ways to deal with loss while they were working with the artists with intellectual disability: “We remember them in art, their spirit lives in our memories.” (Student 2). Their involvement in the project impacted them at a personal level beyond being museum support staff. For instance, one student reflected,

Even though death is an extremely hard topic to approach, we worked through many memories and happy times that he had with him into his art. My own grieving has progressed through his project as I find myself making art about my aunt who passed away in September. (Student 4).

The artists’ unique and honest ways of understanding and processing their loss experiences seemed to indirectly impact the students’ perception of grief: “He has helped me come to terms with life after the death of a loved one.” (Student 2); “they can share an intimate story and laugh at the same time” (Student 7); and “I had never talked about death to this extent with people.” (Student 8)

Discussion

With a shared life topic of grief, this project demonstrated an inclusive community art practice producing “ripples of learning” where multi-layered participants may gain expanded growth and learning opportunities beyond their assumed roles (e.g., exhibitors, museum educators, students, community: Elliott & Clancy, 2017); university students from a community museum education course facilitated the multivocality of community perspectives, and artists with intellectual disability curated grief related personal stories for a public art exhibition. The uniquely matched interests of two groups created a truly interactive, meaningful, and productive space for all members. Noticeably, the results confirmed the compatibility and accelerated effects of multivocality and inclusive arts practice in which respecting diverse voices of people, creativity, and reflectivity are the central values.

Expressive Arts-Based Conversation as a Vehicle for Multivocality Practice

The current study results confirmed that the creative arts-based group interaction can provide a platform to promote an equal member relationship with different backgrounds and skill levels, so that everyone can be “included” (Carrigan, 1994; Reynolds, 2002). With expressive arts as the communication tool, university students were able to facilitate the multivocality of community perspective by giving artists with intellectual disability the space to lead the group conversation on a difficult life topic of grief.

Having prior experiences/trainings about grief and loss through art-based grief workshops provided a foundation for the artists with intellectual disability to have confidence and take control of the group conversation. This underlines “providing foundation and framework for setting” is an important starting point in the Fox and Macpherson’s (2015) inclusive arts practice. Although the students were not informed about specific strategies to conduct an inclusive project with people with intellectual disability, by working together and facilitating multivocality practice, they spontaneously developed strategies. Interestingly, the key elements that we found in the study were parallel to these with inclusive arts professionals who have worked with people with intellectual disability for a long time. These elements include providing frameworks and foundations as starting points, taking a group journey with an open mind, securing plenty of time, having choices and freedom, being patient, developing a trusting relationship, being open to all forms of communication/expression, being reflective, and seeking answers in the participants (Fox & Macpherson, 2015).

Through arts-based group dialogue, students had experiential learning opportunities not only to get to know the artists with intellectual disability but also to experience their capacity as a human being to deal with a shared life event of death and grief and to share their insights about their life stories. This seemed to have a great impact on their general prejudice on the capacity of people with intellectual disability, and the potential to break barriers to truly work as capable project collaborators.

Time, Space and Dialogue, Giving Voice to a Community Group through Multivocality Practice

The 6 weeks of experiences by the artists with intellectual disability in an intentional curating process was only possible with the dedicated time and presence of students from the community museum education course who learned about the fundamental premise of museum community exhibition space—multivocality of community perspectives (Pegno & Farrar, 2017). As the artists with intellectual disability had varied literacy skills, it was critical to have students’ support who accepted the responsibility of documenting and remembering details in the process. Each group also developed museum wall labels as supplemental materials which together best represented their voices in this public exhibition.

By exploring the concept of grief and emphasizing the multivocality in exhibitions, this field project helped them to consider the active roles museums can play in creating meaningful experiences in these spaces with, instead of for, community members. The students learned that, as educators and curators, they were not taking the lead in designing exhibitions and programming, but they were instead creating space for communities to vocalize their own experiences.

Because of the trusting, quality group relationship with familiarized vocabulary and communication styles (e.g., gestures and drawings) that they built during the weekly sessions, artists seemed to also gain confidence in leading group conversation to share stories about their family members and loss experiences, and bring visual supplements, such as pictures from their homes. This allowed the group to “travel together creatively to an unknown destination” (Fox & Macpherson, 2015, p 81), a key concept of inclusive arts practice. This supportive and intentional group interaction not only produced clear visions and detailed art plans as to what they wanted to accomplish for this public exhibition, but also impacted the artists’ professionalism, dedication and the quality of artistic work.

As documented in the qualitative results, some students initially presented hesitation and identified communication challenges working with artists with intellectual disability who have varied literacy skills and expression styles on the sensitive topic of grief. However, this hesitation might be evidence of students’ conscious efforts to practice multivocality (Pegno & Farrar, 2017), representing the voices of artists with intellectual disability as museum educators. This mirrors reflectivity and seeking answers from participants in the inclusive arts practice (Fox & Macpherson, 2015). Through the six weeks of group interactions, the majority of students adapted non-verbal forms of communication, such as drawing, coloring, and gesturing, and became comfortable with having conversations with the artists. Through repeated interactions and conversations around this shared topic of grief, facilitator-community artist relationships were slowly but surely developed.

They also learned how to best support the capacity of focused artists with intellectual disability to articulate and craft fuller stories—paying attention to their unique communication styles, providing repeated and layered opportunities, and assisting them to remember and gather pieces of information together. Thus, they became stronger museum educators who can facilitate developing participant-directed community exhibitions through “collaborative, participatory, and non-hierarchical” approaches of the contemporary pedagogical museum practice (Reid, 2016).

In summary, this has a broader implication that the multivocality practice can work well if it is implemented with expressive arts or other alternative expressions as a communicative tool for other community groups with literacy challenges (e.g., refugee, patients with brain injury, young children). Conversely, the utilization of alternative communication modality could expand full implementation of the multivocality of practice when a group works on a life topic that may be difficult, described in traditional written and spoken modalities even with a community group with good literacy skills.

Limitations and Implications

This project was built upon a clear structure and time frame within a course activity, and thus, we should cautiously interpret and implicate the current study with given limitations. First, the Grief Project pilot study and student involvement were carefully planned and conducted by a multi-disciplinary team, including a certified grief counselor, a graduate social work student, and a museum education professional, and only targeted volunteered individuals who did not require individual therapy and/or pharmacological treatment. To implement this in a community, planning and screening of appropriate participants by a skilled team should be considered.

Second, this study was conducted with a small convenient sample of artists with intellectual disability from an art studio and a classroom who share a broader university community. Both university students and artists with intellectual disability had prior training and experiences to take their specific roles in this project. University students had knowledge of “multivocality,” “artist-directed,” and “collaborative, participatory, and non-hierarchical” art practices (Pegno & Farrar, 2017; Reid, 2016) from their class, whereas the artists with intellectual disability were comfortable having conversations about their personal experiences with university students because they had regular encounters with university students, and conversations about their personal experiences with varied art media. For obtaining fluency and confidence in navigating expressive art and multi-population interactions, persons with intellectual disability may require a space/community for regular instruction, encouragement, and practices using expressive arts as their means and/or supplements of expressing their ideas and thoughts.

Conclusion

Marstine (2007) wrote that university students who have practice-based curatorial experiences as undergraduates may better imagine themselves as agents of change and future leaders of the field. The experiences the students gained in this project emphasized the role of university art museums as sites for students to make connections not only to works of art, but also to new communities and ideas. Although the planning for the exhibition took place outside of the walls of the museum, students worked with the artists to create an exhibition that would communicate the shared experiences of loss and memories. Students developed experience working as museum educators with the artists with intellectual disability to help them bring their ideas to fruition. The artists communicated through their stories using art and their own words, honoring memories of loved ones through these shared experiences.

Greene (1995) relied on the imagination to create empathy and “cross those empty spaces between ourselves and those we teachers have called ‘other’” (p. 3). She wrote, “We must want our students to achieve friendship as each one stirs to wide-awakeness, to imaginative action, and to renewed consciousness of possibility” (p. 43). By communicating and working together, students and artists with intellectual disability were able to elevate inclusive voices, and the stories the artists told in the art museum so that the work that they created could then be shared with visitors from the community and the university.

Acknowledgement

This project was partially funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, Art Works Program (17-5400-7040), the Arizona Commission on the Arts (7817865), and the Molly Lawson Foundation to the first author to conduct the grief support group and the public art exhibition that provided foundation of the current manuscript. The preliminary results of the manuscript was presented at an annual conference of the American Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities conference as a poster presentation, titled Creating an Art Exhibition Through the Shared Experiences of Grief: Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and University Students. We thank the University of Arizona Museum of Art and the Curator of Community Engagement, Chelsea Farra, the Department of Art & Visual Culture Education, and ArtWorks Studio and Gallery for their partnerships and collaborations.

References

- Assarroudi, A., Heshmati Nabavi, F., Armat, M. R., Ebadi, A., & Vaismoradi, M. (2018). Directed qualitative content analysis: The description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. Journal of Research in Nursing, 23(1), 42-55. doi:10.1177/1744987117741667

- Carrigan, J. (1994). Paint talk: An adaptive art experience promoting communication and understanding among students in an integrated classroom. Preventing School Failure, 38(2), 34-37.

- Clute, M. A. (2010). Bereavement interventions for adults with intellectual disability: What works? Omega, 61(2), 163-177. doi:10.2190/OM.61.2.e

- Doka, K. J. (2010). Struggling with grief and loss. In S. L. Friedman, & D. T. Helm (Eds.), (pp. 261-271). Washington, DC: American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

- Elliott, L., & Clancy, S. (2017). Ripples of Learning: A Culturally Inclusive Community Integrated Art Education Program. Art Education, 70(6), 20–27.

- Fox, A. & Macpherson, H. (2015). Inclusive Arts Practice and Research: A Critical Manifesto. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Gokcigdem, E. (2016). Introduction. In E. Gokcigdem, (Ed.), Fostering empathy through museums (xix-xxxii). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Harwood, V. (2010). The place of imagination in inclusive pedagogy: Thinking with Maxine Greene and Hannah Arendt. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(4), 357-369.

- Kolb, D. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Pearson Education.

- Lavin, C. (1989). Disenfranchised grief and the developmentally disabled. In K. J. Doka (Ed.), Disenfranchised grief: Recognizing hidden sorrow. (pp. 229–237). Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Com.

- Marstine, J. (2007). What a mess! Claiming a space for undergraduate student experimentation in the university museum. Museum Management and Curatorship, 22(3), 303-315.

- Pegno, M. & Farrar, C. (2017). Multivocal, collaborative practices in community-based art museum exhibitions. In P. Villeneuve & A. Rowson-Love (Eds.), Visitor-centered exhibitions and edu-curation in art museums (169-181). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Reid, N. (2016). The university art museum and institutional critique: A platform for contemporary practices. The International Journal of the Inclusive Museum, 9(4), 1-15.

- Reynolds, F. (2002). An exploratory survey of opportunities and barriers to creative leisure activity for people with learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30(2), 63-67. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3156.2002.00151.x

- Young, H., Hogg, J., & Garrard, B. (2017). Making sense of bereavement in people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: Career perspectives. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual disability 30(6), 1035-1044. doi:10.1111/jar.12285

Appendix

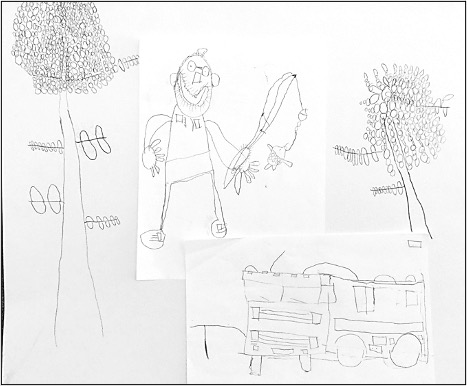

Example 1 By Joey Aschenbrenner:

Drafted stories during the group sessions.

“One of my favorite memories of my dad, who passed away December 9, 2018, is camping in Patagonia. My dad, mom, cousin Kurt and I, would take a camper to a special lot at Patagonia lake, lot 32. In this painting, my dad and I are fishing and enjoying a fire on the special bench he liked. This summer, I am going camping with Kurt and my mom, to sit on the bench and remember my dad. To make this piece, I used pictures of my family to practice drawing everyone to capture the way they look and to have accurate details. I drew each person’s hands at least 3 times, about 30 hands! This ensured each person would be distinctive. In the end, I drew everything on separate pieces of paper until I was happy with the details, then cut each piece out and pasted it to the bigger paper.”

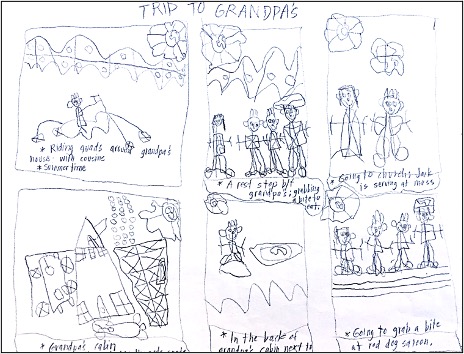

Example 2 By Jack McHugh:

Drafted stories during the group sessions.

“My Grandpa Mac lived in Jarbridge, Nevada where our family would gather and spend time together at his cabin by the lake, enjoying each other’s company and telling funny stories. Grandpa was always prepared and had a place in his cabin called “the soda spot” where cold sodas of all kinds were stored in a special fridge for us to enjoy. We would also spend time together by going to church and then going out to eat afterwards. This piece is about how important my grandpa was to my family, and what an amazing storyteller, pianist, and wonderful man he was. I decided to make this piece in the style of a comic strip because I have several different memories that I wanted to draw, and putting them in separate boxes worked best. I worked on each box separately and blocked all the other ones so I could focus on each memory and get the details right. I decided to make this piece more realistic so I practiced on separate paper before I worked on the final piece. I am glad I chose this process because I learned new principles of art, like perspective and proportion.”