From the Standpoint of Employees with Disabilities: An Analysis of Workplace Accommodation Processes in the Non-Profit Sector

Point de vue du personnel handicapé : une analyse des processus d’accommodement en milieu de travail dans le secteur sans but lucratif

Alexis Buettgen, PhD

Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Economics, Assistant Clinical Professor (Adjunct), School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University

a [dot] buettgen [at] gmail [dot] com

Abstract

This article presents an institutional analysis of workplace accommodation processes for employees with disabilities in three Ontario non-profit service organizations that were considered sites for inclusive employment. This article helps to fill a gap in empirical research on alternative approaches to workplace accommodations, and how the use of medical documentation creates a culture of distrust, and barriers to inclusion and a sense of belonging. We offer an articulation of resistance to medical documentation in accommodation processes in which an employee’s representation that they are disabled establishes that they are disabled and allows them to have power and control over their accommodations.

Résumé

Cet article présente une analyse institutionnelle des processus d’accommodement en milieu de travail pour le personnel handicapé de trois organismes de services sans but lucratif ontariens qui étaient considérés comme des environnements de travail inclusifs. Cet article aide à combler une lacune dans la recherche empirique sur les approches différentes en lien avec les accommodements en milieu de travail et sur la façon dont l’utilisation de la documentation médicale crée une culture de méfiance ainsi que des obstacles à l’inclusion et au sentiment d’appartenance. Nous proposons une articulation de la résistance à la documentation médicale dans les processus d’accommodement dans laquelle l’auto-identification d’une personne est suffisante pour établir qu’elle est handicapée et lui permet d’avoir le pouvoir et le contrôle sur ses accommodements.

Keywords: Employees with disabilities; accommodation process; policy; non-profit sector; human rights; institutional analysis

Introduction

Over the last forty years, there has been an evolution in thinking about disability-inclusive employment. Disability inclusion is evolving in terms of how it is conceptualized and operationalized in the workplace. This article responds to the current need for guidance on how to center the lived experience of disability and resist the use of medical documentation in workplace accommodation processes. Empirical research on resistance to medical documentation in workplace accommodations is relatively scarce. Thus, there is little knowledge on how adoption of alternative approaches and, particularly a more genuine human rights approach, plays out in the workplace. The aim of this paper is to help fill a gap in knowledge about how employees with disabilities experience accommodation processes and forms of everyday resistance to the medical model. The focus is on organizations in the non-profit service sector, as it is seen by some as being more responsive to the needs of employees with disabilities.

Historically, disability in the workplace focused on the need to “cure” or “rehabilitate” individuals with disabilities to better fit into the labour market rather than looking to societal norms and practices that could be modified to better accommodate persons with disabilities (e.g., Devlin & Pothier, 2006; Oliver, 1990a). This discourse was steeped in the medical model of disability which locates the ‘problem’ of disability within the individual and focuses on individual functional or psychological limitations which are assumed to arise from anomaly in health and function. Criticisms of the model are based on the failure of medical professionals to meaningfully engage persons with disabilities except as objects of intervention, treatment and rehabilitation (Finkelstein, 1980; Oliver, 1990b).

The medical model has had oppressive consequences for the employment of persons with disabilities because it focuses on an individual's limitation(s) and challenges to fit into society. As a result, persons with disabilities experience significantly lower employment rates than persons without disabilities (e.g., International Labour Organization; Morris, Fawcett, Brisebois, & Hughes, 2018; Shaw, Wickenden, Thompson, & Mader, 2022). This is due, in part, to the out-dated way of seeing disability through the medical gaze.

The social model developed in response to the medicalization and individualization of disability (Oliver, 1990b). Pioneered by disabled activists, this model views disability as the interaction between people living with functional impairments and the physical and social barriers that limit or disable their full participation in society. The social model conceptualizes disability as a social construction and changes the focus of the problem away from the individual and toward societal norms, practices and structures to understand the barriers persons with disabilities experience.

Currently, there is growing recognition of the human rights model of disability to further counter the medical model and promote the right to work. The human rights model conceives persons with disabilities as diverse rights-bearing citizens and addresses the physical, economic, institutional, and social barriers that undermine their rights and dignity (Degener, 2016). In terms of employment, a disability rights perspective focuses on barriers in the world of work, and the legal and policy solutions through which they can be dismantled. This perspective recognizes the right of persons with disabilities to work on an equal basis with others; and is informed by principles of respect for inherent dignity, individual autonomy, freedom to make one’s own choices, respect for difference, and full and effective participation, inclusion and accessibility (UN General Assembly, 2007).

Despite legislative commitments to human rights in Canada and elsewhere[1], many workplaces remain inaccessible, and accommodations are required to support engagement of persons with disabilities. Workplace accommodations are modifications and adjustments to a job or the work environment when barriers have not or cannot be removed (Conference Board of Canada, 2012, p. 24). Accommodations can be temporary or permanent, depending on the needs of individual employees and the design of the workplace; and may include flexible workplace policies and practices, modified work duties, assistive devices and technology, environmental / physical adaptations, as well as training and support. Accommodations, when implemented appropriately, can be effective in supporting and maintaining the employment of persons with disabilities (Nevala, Pehkonen, Koskela, Ruusuvuori, & Anttila, 2015; Padkapayeva et al., 2016). Accommodations to enhance workplace flexibility, employee autonomy and strategies to promote inclusion and integration are especially important (Padkapayeva et al., 2016). However, accommodations can be problematic when employers take a narrow focus on individual employee limitations, rather than overall workplace context and culture (Gates, 2000; Sanford & Milchus, 2006).

The approach taken by many organizations to fulfil their obligations under human rights can exacerbate the situation by continuing to frame disability within the context of the medical model. Specifically, the requirement to provide medical documentation for a disability-related accommodation focuses on the individual, rather than disabling barriers, and situates disability as a body ‘problem’. For example, Saltes (2020) analyzed accommodation policies across Canadian universities and argued, “Requiring medical professionals to validate the presence of disability [in the accommodation process] reinforces the view of disability as pathology and limits disabled people’s capacity to define their own experience and needs” (Saltes, 2020, p. 77). This documentation may include doctors’ notes, or other forms from healthcare professionals.

Likewise, Macfarlane (2021) found that “A system in which doctors, but not disabled individuals themselves, are consulted to determine whether disability exists, and how it should be accommodated, embraces the medical model of disability.” (Macfarlane, 2021, p. 19). Macfarlane argued that the use of medical documentation conflicts with the intentions of the human rights model such that, “The medical documentation requirement is likely influenced by the widespread belief that people who claim disability are faking” (p. 4). They suggest that employers who have never experienced disability may treat most disabilities as unknown, and therefore in need of documentation. The fear that people are faking disability influences the legal rules surrounding disability accommodation and creates a system in which employees must demonstrate that they are worthy of accommodation.

Continued reliance on the medical model can be understood with considerations of how persons with disabilities are categorized in the labour market. For example, Stone (1984) described how clinical judgments rose to prominence to eliminate abuse of social assistance by impostors of disability. She describes the use of medical assessment as arising from political conflict about distributive criteria for social aid. Use of medical documentation in the accommodation process indicates that individuals' subjective experiences of impairment are irrelevant unless validated by healthcare professionals who can measure, categorize and document impairments and their functional impact. Krebs (2019) argues that the use of medical documentation forces persons with disabilities to engage with a system that has been oppressive and violent. It negates a desire to abandon a focus on limitations over abilities and medicalized definitions of disability.

Previous literature argues for the establishment of accommodation policies and procedures that proceed without medical documentation and defer to employees’ experiences to convert the process from one controlled by suspicion into one based in trust (e.g., Macfarlane, 2021; Saltes, 2020). Centering the experiences of employees with disabilities would eliminate time spent on collecting and reviewing medical documentation thereby avoiding the expense created by such documentation requests. Eliminating use of medical documentation requires new guidance and training for employers accustomed to questioning, rather than accepting, disability.

Research Context

The Ontario Non-Profit Service Sector

This paper draws on the experiences of employees with disabilities in the non-profit service sector (NPSS) in Ontario, Canada, the most populous province in the country. The NPSS is composed of organizations defined by their “orientation to serve a public or group good, through private non-profit-making organizational forms” and typically driven by a mission to serve marginalized communities (Baines, Cunningham, Campey, & Shileds, 2014, p. 76). It consists of approximately 14,000 organizations, 150,000 full-time employees, and 100,000 part-time employees (Statistics Canada, 2009; Van Ymerman & Lalande, 2015).

The NPSS was selected because of its social agenda and potential for meaningful employment opportunities for persons with disabilities. Previous literature suggests there may be a greater willingness to accommodate employees with disabilities in the non-profit sector versus the for-profit sector (Buettgen & Klassen, 2020; Prince, 2014; Wilton, 2006; Wilton & Schuer, 2006). For example, Wilton and Schuer (2006) found evidence of this in their study of the experiences of employees with disabilities in various industries in Ontario. They noted the greater frequency of accommodation in non-profit workplaces, which is not surprising given their organizational mandate to provide support to people and communities. Moreover, Van Ymerman and Lalande (2015) suggest that non-profit organizations can act as champions of working conditions and policies that ensure dignified and supportive work environments given their social agenda.

Legislative Context: The Right and Duty to Accommodate

In Ontario, the Human Rights Code (hereafter referred to as the Code) has primacy over all other provincial legislation and is governed by the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC). Prohibition of discrimination based on disability is included in the Code as well as accommodation of the needs of persons with disabilities up to the point of undue hardship, considering cost, sources of available funding, and health and safety requirements. The OHRC’s Policy on Ableism and Discrimination Based on Disability covers the parameters and limitations of the duty to accommodate in Ontario. The policy includes guidance on inclusive design and allows for the use of medical documentation in the accommodation process. The policy states that “the procedure to assess an accommodation (the process) is as important as the substantive content of the accommodation (the accommodation provided)” (Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2016, p. 29).

Section 8.2 of the OHRC policy focuses on ‘inclusive design’ which “requires those who develop or provide policies, programs or services [including employers] to take into account diversity from the outset” (p. 32). When properly implemented, “[Inclusive design] removes from persons with disabilities the burden of navigating onerous accommodation processes and negotiating the accommodations and supports that they need to live [and work] autonomously and independently” (p. 32). This “proactive approach” designs for accessibility and inclusion from the start, thereby minimizing the need to ask for accommodation.

When accommodations are required, Section 8.7 sets out guidance about medical information that may be used to support an accommodation request. This section notes that the employer, “may request confirmation or additional information from a qualified healthcare professional” (p. 48). An employer’s “reasonable request” is determined according to whether “there is a reasonable basis to question the legitimacy of a person’s request for accommodation or the adequacy of the information provided” (Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2016, p. 46). The employer may then request further information and confirmation from a healthcare professional.

In sum, the duty to accommodate requires employers to take requests for accommodation in good faith. Employment must be designed inclusively or adapted to accommodate persons with disabilities in a way that promotes integration and full participation. However, persons with disabilities may also be required to provide information from healthcare professionals about their “functional limitations and needs”. Thus, the Code and subsequent OHRC policy permits the medical model to enter the accommodation process. It gives employers permission to question the legitimacy of disability-related accommodation requests and thereby situates disability accommodation at the individual level rather than the institutional level. Conversely, situating disability accommodation at the institutional level focuses on how the environment, including norms, rules, and values, influences the organizational structure of work for persons with disabilities.

Methods

The present study draws from institutional analysis to explore workplace accommodations in the Ontario NPSS and to extract forms of organization that coordinate employees’ activities at work (Hollingsworth, 2000; Smith, 2005). A criterion-based purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit participants from three Ontario NPSS organizations in 2017, that had received external recognition for exceptional workplace diversity and inclusiveness programs and/or had a documented history of employing persons with disabilities. To protect confidentiality and anonymity, the three organizations are referred to as Organization A, Organization B, and Organization C, and pseudonyms are used for individual participants.

Participants

Organizations A and B were small (less than 50 staff) organizations of persons with disabilities (OPDs) that provided disability services and had a history of employing persons with disabilities. As OPDs, both organizations were led by a board of directors whose members included a majority of persons with disabilities and 30 to 40 percent of staff identified as persons with disabilities.

Organization C was not an OPD and had a broader mandate of services for individuals and families with and without disabilities. Organization C had received awards for diversity and inclusion in the workplace. This large, unionized organization had more than 500 staff members, with approximately six percent identifying as persons with disabilities. Table 1 summarizes key features of these organizations.

| Organization | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total budget | Over $10,000,000 | Less than $1,000,000 | Over $10,000,000 |

| Total number of staff | Less than 50 | Less than 50 | Over 500 |

| Percentage of total staff who identified as persons with a disability | 30% | 40% | 6% |

| Organizations of persons with disabilities (OPD) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Unionized | No | No | Yes |

Interview participants included six senior leaders (e.g., executive directors [ED], directors, human resources [HR] representatives, and union representatives) and nine front-line employees with disabilities, all of whom took part in in-depth interviews that were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Two senior leaders were recruited from each organization. Three employees with disabilities were included from Organization A, two from Organization B, and four from Organization C. All participants were employed in full-time positions, most of which were permanent. Participants are primarily identified by their position in the institutional work process (e.g., employee, ED, HR representative, or union representative). Much personal information about participants is suppressed to keep the focus on the institutional processes they described (DeVault & McCoy, 2006).

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants that lasted approximately one hour. Interview topics included participants’ experiences in their current job and their reflections on the accommodation process. Following Hollingsworth’s components of institutional analysis, the interview process involved listening for texts that stood for the organization’s norms, rules, conventions, habits and values (e.g., laws and legislation, organizational policies and forms) (Hollingsworth, 2000). Specifically, this study attended to institutional texts that were active in workplace accommodation processes for employees with disabilities. As such, data collection also involved an analysis of organizational documents, including HR policies and procedures, accessibility policies, and sample accommodation plans, as well as relevant laws, policies, and legislation informing organizational documents.

The Office of Research Ethics at York University reviewed and approved all study procedures.

Data Analysis

Data analysis started with verbatim transcripts from interviews with employees with disabilities to discern their subjective experiences in workplace accommodation processes. Analysis then proceeded to investigate how the structure of the workplace included or excluded employees’ experiences. Perspectives and explanations of events from interviews with senior leaders at each organization were also included. Questions of validity involved referencing back to employees about what they described during interviews.

Organizational documents and relevant laws and policies offered an additional source of data to verify what participants described. The subsequent analysis examines each organization’s accommodation policies as “active texts” to discover how these texts linked with employees’ experiences and institutionally organized practices (Prodinger & Turner, 2013). These texts were mapped as they occurred (i.e., were “activated”) during the accommodation process. This also included how higher order “governing” texts came into play. The Code, as a governing text, regulated the relevant accommodation policies at Organization A, B and C and projected the organization of employee’s experiences of the accommodation process. The following sections are an analysis of how different readings of the Code and OHRC policy operated in accommodation processes at Organization A, B and C.

Findings

In accordance with the Code, all three organizations followed a similar process of recognizing the need for accommodation; gathering relevant information and assessing needs; writing an accommodation plan; and implementing, monitoring and reviewing accommodations. The process was the same within each organization regardless of accommodations costs. However, there were distinct sequences of action in the accommodation processes at each organization.

Organization A

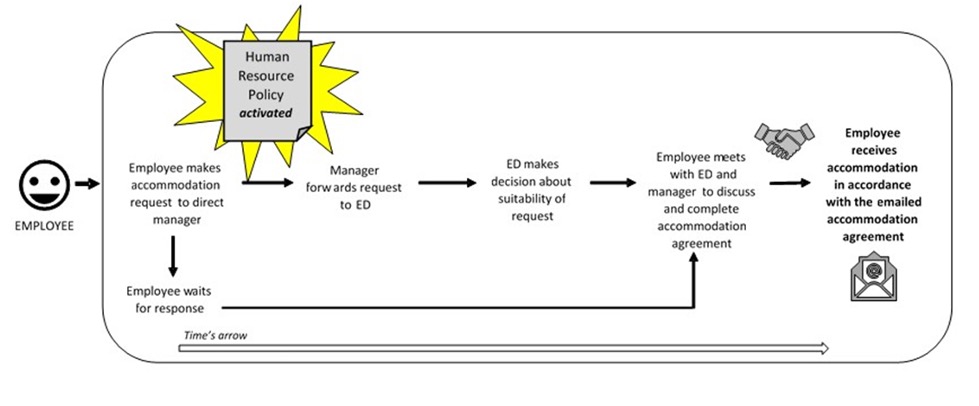

At Organization A, the accommodation process started when employees made an accommodation request to their manager, who forwarded it to the ED. This request activated Organization A’s HR Policy which stated:

[Organization A] fully supports efforts that identify and neutralize any past or present discriminatory practices in all aspects of employment and advancement. For this reason, the policy of [Organization A] is to incorporate into the employment practices the meaning and intent of the Ontario Human Rights Code.

Following this policy, the ED reviewed accommodation requests by considering employee’s needs, costs of potential accommodation(s), organizational budget, the employee’s job requirements, and workplace health and safety. After reviewing the request, the ED, employee and their manager discussed how to implement accommodations to best meet the needs of the employee and the organization. Typically, accommodation requests and approvals were sent via email between the employee, their manager and the ED. This was considered the accommodation agreement. Figure 1 illustrates this process.

Management encouraged employees to request accommodations by asking about their needs upon hiring and through ongoing informal conversation with all staff. As an OPD, Sarah (the ED) said they wanted their workplace to reflect the forms of accessibility and inclusion promoted in their services. Sarah acknowledged that their organization’s budget allowed them to afford accommodations as part of the “cost of doing business”. Sarah said management would rely on employees to tell them what they needed to do their job. She did not want employees to have to “justify” or “explain”, such that, “You don’t have someone second guessing your [needs and] decisions.” Likewise, Quinn (a director) said,

It’s not part of our ethos to ask for a doctor’s note saying why you [need an accommodation]. We’re trusting the individual to assess their own abilities… We pride ourselves on accommodating people with disabilities. Besides it being a human rights and legal obligation, the fact is we’re a disability organization, if we are getting this wrong, we have a serious problem on our hands. For me, it’s part of the furniture, so to speak.

Quinn described their wheelchair accessible office kitchen and bathrooms, tables and desks that lower and raise, railings on the walls and colour contrasted flooring. Employees said the environment and accommodation process at Organization A worked well for them because management had knowledge of disability rights and issues. For instance, Deidre (an employee) described,

One of the perks of [my job] is in terms of accommodation. I feel very accommodated…When [I got this job] one of the questions [management] asked me was ‘What sort of accommodation would you need?’…I was able to negotiate hours where I could leave at a specific time and…there was an understanding, and trust that I will not abuse that.

Deidre described her experience of an assessment for each employee to discover accommodation needs. When Deidre described her flexible scheduling as an accommodation, she described a sense of job satisfaction and trust from management.

Another employee, Monica, said employees work together in job-sharing situations, to “find a way to make it all work”. Indeed, Monica commented that formal procedures in the workplace only “bogged down” the accommodation process such that informal approaches based on trusting relationships between management and employees worked well. Upon reflection of the Code and other employment laws, Sarah said, “The system doesn’t [help]. People in the system do…In fact, the system is designed to put as many barriers in place as possible. [As an employer], you have to be very creative about working around [and within] it.”

Organization B

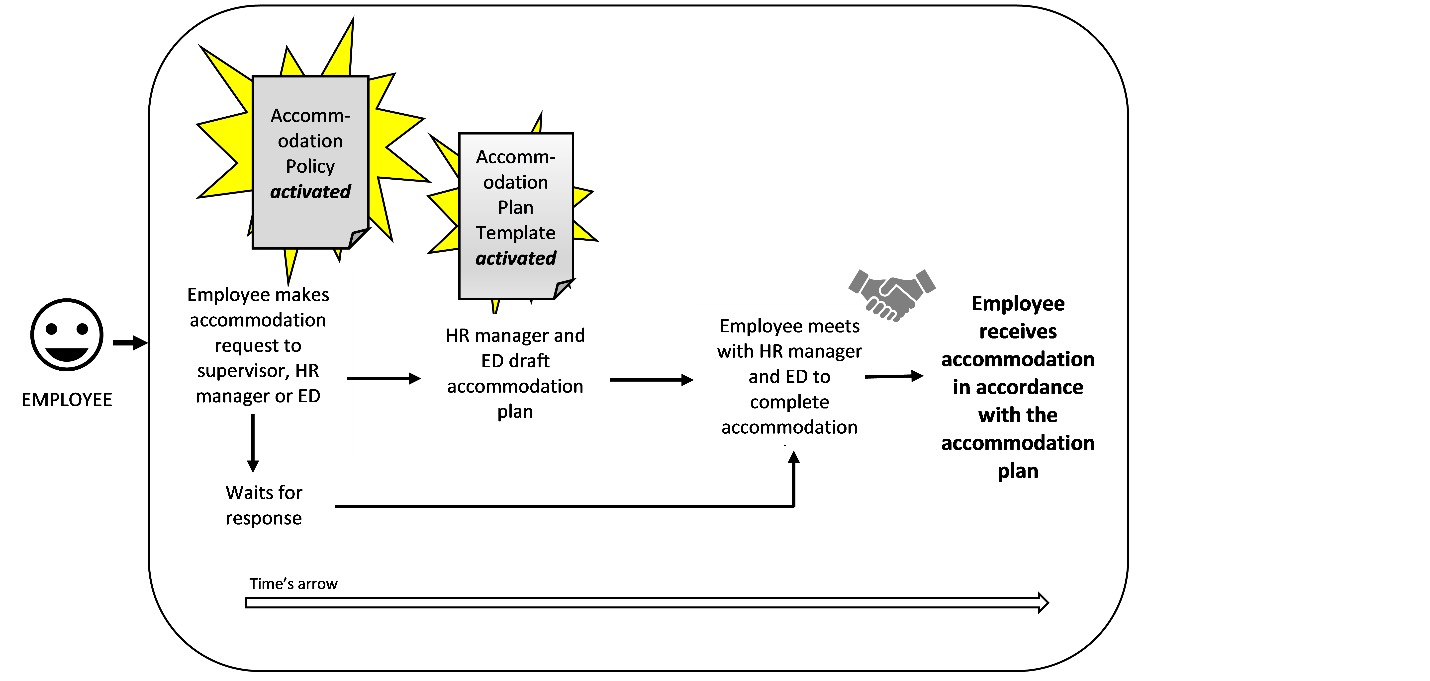

At Organization B, employees seeking accommodation were required to communicate their needs to their supervisor, HR manager or ED. This request activated Organization B’s Accommodation Policy. Accordingly, employees were asked about existing barriers to their performance or participation in the workplace, and potential accommodation options. This information was used by HR and the ED to draft an accommodation plan using Organization B’s Accommodation Plan Template.

Next, the ED and HR manager invited the employee to discuss and negotiate the draft accommodation plan. The plan template was used to document employees’ identified needs, accommodations to be provided and implementation plan. This process is illustrated in Figure 2.

Employees felt their “needs and concerns” were supported during this process. For example, Faith said, “Even though I work in the [disability] field, I still don’t realize how I should ask for accommodation and what I have rights to.” Faith said that during the accommodation process, “I was able to give my opinions about things that should be included or excluded [in the accommodation plan]. The executive director would provide some thoughts from a human rights perspective…It makes me feel like they’re there for me.” Similarly, Susan said, “Frankly…I have absolutely no problem saying that my accommodation needs have changed. Like I’m going to have to work at home more often or going to need a different work schedule or I have more medical appointments coming up.”

At Organization B, employees’ perspectives were taken as priority information in the development of accommodations. Brett (the ED) said:

We try to [develop accommodations] the way it should be developed based on all the regulation and everything we know about the duty to accommodate [under the Code] …We meet and talk about what the issue is, and we talk about possible solutions. In my experience…that’s kind of enough. I haven’t been in a situation so far where I’ve needed medical information to provide the accommodation. So as far as my duty to inquire, I’ve fulfilled my duty just by meeting with the staff.

Brett’s talk presented a reading of the Code as flexible and demonstrated knowledge of the legal duty to accommodate using a proactive approach. Brett said:

We’re really proactive, and there’s always room for improvement but we try to be vigilant…For example, we’re now in a process of investigating how we distribute [workloads], and how we create a team. So, the way that job descriptions have been set up, and the way that division of labour has been set up, may or may not be problematic from a disability accommodation perspective…Like let’s just start from scratch! Let’s just figure out a model that will alleviate some potential barriers and accommodation issues that we’re experiencing and just try to wipe the slate clean and create something… given the needs around the table.

Brett described their efforts to create a model of work that recognized the diversity and uniqueness of each individual employee. In this way, Brett referred to considerations of inclusive design of job descriptions and division of labour.

Organization C

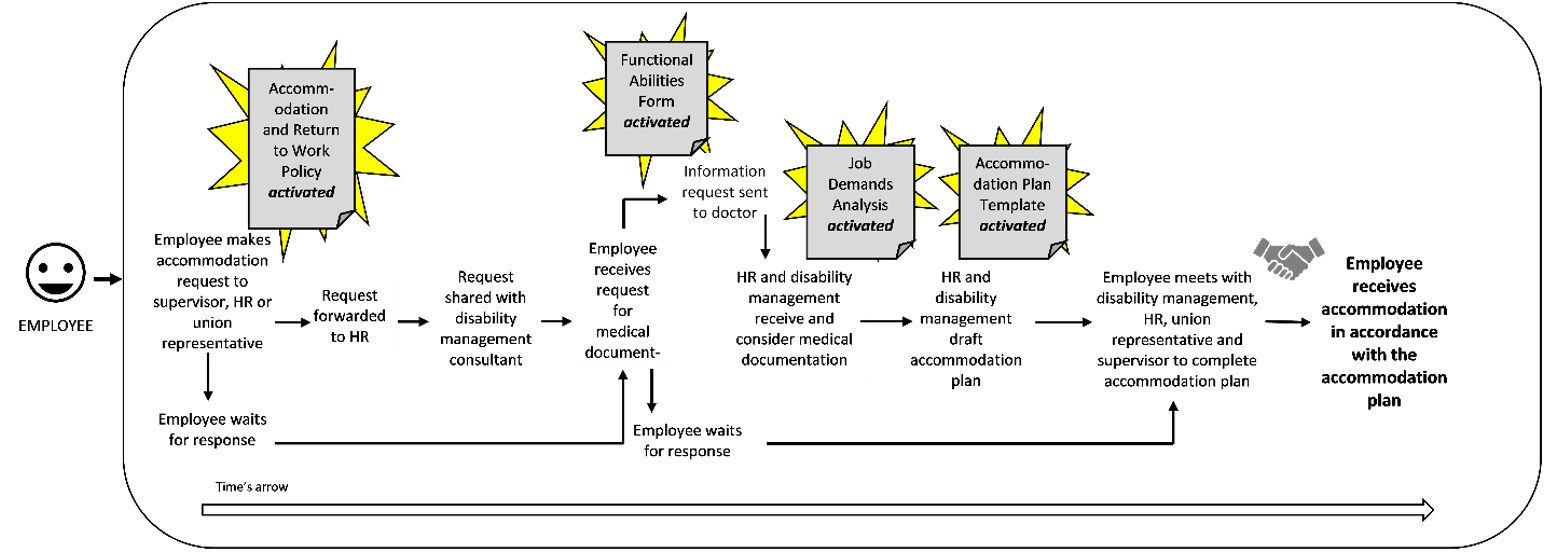

At Organization C, employees seeking accommodation were required to make a request to their supervisor, union representative or HR. This request activated Organization C’s Disability Accommodation and Return to Work Policy which was explicitly informed by the Code. According to this policy, employees were required to “communicate an accommodation need; provide all relevant and pertinent information; Co-operate with the implementation of accommodation measures and advise if any revisions are required.” The policy stipulated that accommodation requests must be received by HR who would share this request with an external disability management specialist. With the employee’s permission, the disability management specialist would contact the employee’s doctor to collect information about their functional limitations using a Functional Abilities Form that included information about the cognitive and physical demands of the employee’s job. This information was received by HR and disability management specialist who determined whether the employee’s functional limitations (as noted by their doctor) were bona fide requirements of their job (as noted in their Job Demands Analysis document) which determined whether they were accommodated in their current position or another vacant position in the organization. This process led to a draft Accommodated Work Plan using Organization C’s Accommodated Work Plan template. The template was used to document accommodation objectives and activities, the position offered to the employee, whom the employee would report to, and contact information for the employee’s doctor. The template was also used to document the employee’s functional restrictions and limitations.

The accommodation plan was presented to the employee in a meeting with their supervisor(s), an HR representative and a union representative (if requested by the employee). The meeting was facilitated by the disability management specialist who reviewed information on the employee’s limitations according to the medical documentation received. Then the specialist and HR representative would present the accommodation plan to the employee to review, ask questions, etc. When the plan was finalized, the employee received their accommodation. Figure 3 illustrates this process.

Upon reflection on this process, several employees were critical of the request for medical documentation and expressed a sense of frustration and intrusion of privacy. For example, Tracy (an employee) described her experience obtaining medical documentation:

I went in to see my doctor…who said: ‘What do they [Organization C] want?’ and I said: ‘They just need a note telling them [about my ailments].’ And [my doctor] said: “It’s none of their business.’ And I was like: ‘I know!’

Likewise, Elizabeth (another employee) said that when she requested an accommodation: “My psychiatrist didn’t like it. He said it was kind of personal stuff… I was worried about it.” Other employees shared this sense of worry and uncertainty about the nature of the information required to support their accommodation requests. Jane described her experience returning to work after a medical leave:

Well I spoke to my doctor, and at first, he wrote this note asking for [my accommodation request] …And I took it to my supervisor and she temporarily accommodated me…and I think she might have spoken to HR and told them about it until we could get in a meeting with the disability specialist…and they had a form for me to have the doctor fill out which is like ‘can you walk up stairs? What weight can you lift?’ All these accommodation questions. My doctor wrote a thing about getting another half hour [break during the day] and then that’s when I went back to the meeting and [the disability management specialist and HR representative] said ‘well we can’t do this’…They said that it’s their [Organization A’s] expertise, they find out how to [accommodate], and it’s the doctor’s role to find out what the limitations are and then it’s their role to fit those limitations into the work schedule...It’s confusing.

In these examples, the perspective of a medical professional, disability management specialist and HR were taken as priority information in the development of workplace accommodations. Employees’ knowledge and experiences of disability were superseded. Alex (union representative) said this process signalled distrust of employees such that:

Everything needs to be based on medical evidence for the employer to move forward…It’s like this: They [the employer] says ‘OK so this is what your doctor said, is there anything you want to add?’ And I say [as an employee] ‘Yeah I can’t drive.’ [Then the employer says], ‘Oh your doctor didn’t write that here. So…we’re going to have to ask your doctor to provide that information.’

Alex said assessments for accommodations were not based on “the word of the employees”. Alex said the process was especially challenging when gathering information to assess needs of employees with invisible disabilities because it is difficult to “see” what an employee can or cannot do. As such, employees with invisible disabilities were required to gather more medical documentation to clarify their decision making, memory and communication abilities.

The process at Organization C centered on information about essential duties of a job and medical documentation as the primary basis for the organization to plan and implement accommodations. As Jamie (HR representative) said:

If we’re [accommodating] someone…we need to have their doctor review things. We’ll send out a cognitive and physical demands analysis and…then we assess whether they are able to…meet the essential duties of the job.

Here, Jamie identified features of the OHRC Policy (i.e., medical documentation; essential duties of the job) that are at the forefront of the organization’s accommodation process. Jamie described how the organization relied on these features as representing what the organization knew about the needs of individual employees. Jamie said that, “One of the things I find challenging is getting employees to think about modifying their expectations around some of the [accommodation] pieces, mostly from our point of view.” Jamie described these challenges in relation to increasing pressure from their funder to demonstrate financial responsibility and efficiency in workplace accommodations.

Discussion

The institutional analysis of data collected for this study shows how particular readings of the Code and OHRC Policy were integral to the implementation of workplace accommodations. Each organization drew from the same governing text of the Code which presents standard guidelines for everyone. However, participants’ translation of those guidelines into organizational policies and practices determined how the accommodation process was experienced by employees with disabilities.

Findings of this study support previous arguments that the medical model of disability influences policies, practices, and workplace accommodation processes (e.g., Krebs, 2019; Macfarlane, 2021; Saltes, 2020). While the discourse of biomedicine was made operative in the development of accommodations at all three organizations, there were distinctive ways in which each organization adopted or resisted medicalized approaches in their accommodation process.

Organization C’s process centered on aspects of the essential duties of a job and the use of medical documentation. As such, when an employee entered the accommodation process, they became an abstraction, through the work of those who reconstructed them as a set of functional limitations. The process detached employees from their experiences, concerns, and autonomy to identify and express their needs. The use of medical documentation invoked a sense of distrust between employer and employees because “everything needs to be based on medical evidence” and not “the word of the employees”. Distrust between employers and employees negatively influences organizational outcomes and employee satisfaction such that without trust, employee skills and knowledge are likely to be curtailed instead of being disseminated through organizational work (e.g., Dirks & Ferrin, 2001; Reychav & Sharkie, 2010). Thus, it is in an organization’s best interests to foster a sense of trust in the workplace.

Despite the presence of a union at Organization C, it did not serve as a critical factor for employees with disabilities. Previous research suggests there may be a negative association between union membership and requesting workplace accommodations. Breward (2016) argued that this negative association may be related to a lack of confidence among employees with disabilities to enforce their rights, and perceived lack of individual voice as opposed to group voice. This research resonates with our findings which suggests that some employees were unsure of their right to accommodations but having a sizeable number of employees with disabilities is a factor in how influential and confident employees with disabilities are in an organization (see also Buettgen & Klassen, 2020).

The importance of employee confidence and power was particularly apparent in Organization A and B, where senior leaders did not request medical documentation from employees, but rather centered the process on employees’ subjective experiences of disability. Taking the word of employees as evidence of their need for accommodation demonstrated trust and resistance to the medicalization of disability regardless of whether or not there was a financial cost associated with it. Senior leaders acknowledged the potential costs of accommodation but were operating with core funding which supported their capacity to provide accommodations as needed and requested. They also acknowledged the possibility of the use of a “doctor’s note” which displayed recognition of the availability of this feature of their duty to accommodate, that they had not taken up in practice. Similarly, their acknowledgement of what was represented in the Code was given, but realization of what happened in the workplace was open to negotiation.

Senior leaders at Organization A and B appeared to take up the social and human rights model of disability through forms of everyday resistance to the medical model of disability (Johansson & Vinthagen, 2020; Scott, 1985). Everyday resistance is about how people act in their everyday lives in ways that might undermine power. This form of resistance is neither individual acts, nor public confrontations, but a complex ongoing process of social construction much like the ongoing social construction of disability. Organization A and B’s resistance to the use of medical documentation in the accommodation process represents a practice or pattern of acts that is countering power but typically hidden and potentially underestimated as a form of confronting ableist norms. This resistance was exemplified when Sarah said that at Organization A, “The system doesn’t [help]. People in the system do…In fact, the system is designed to put as many barriers in place as possible. [As an employer], you have to be very creative about working around [and within] it.” According to Johansson and Vinthagen (2020), resistance can be “mundane kinds of practices of accommodation and non-confrontation, and that resistance can be integrated into our daily life in a way that makes it almost unrecognized” (ibid, p. 2). Thus, in consideration of evolving conceptualizations of disability inclusion in the workplace, it becomes increasingly important to stay alert to such hidden/unrecognized forms of resistance that confront medicalized approaches of disability.

Moreover, senior leaders at Organization A and B talked about disability inclusion as part of their workplace structure and culture. In this way, Organization A and B activated the inclusive design principle of the OHRC policy. At Organization A, senior leaders described their accessible work environment and accommodations as “part of the furniture”. At Organization B, their proactive approach to continually “wipe the slate clean” considering “the needs around the table” represents an ongoing process of inclusive design in how the workplace is structured and functions. Likewise, OHRC Policy states that inclusive design is “preferable to ‘modification of rules’ or ‘barrier removal’, terms that, although popular, assume that the status quo (usually designed by able-bodied persons) simply needs an adjustment to render it accessible” (p. 5). Senior leaders at Organization A and B acknowledged the need for inclusive design from the start and on an ongoing basis.

The above discussion builds on Stone’s suggestions, to examine social policy according to “how particular constructs and measures systematically exclude certain understandings and include others”, and how they work to produce certain types of results (Stone, 1984, p. 117). We have examined OHRC policy measures and relevant actors (i.e., employers and medical professionals) that serve as gatekeepers of assistance and accommodations for persons with disabilities. Previous literature describes the power of the medical profession and systemic failure by governments in law, and by the private and non-profit sectors in policy and practice, to effectively realize the social and human rights models. These are key reasons why the medical model of disability continues to be used to determine eligibility to services and supports for persons with disabilities (e.g., Frazee, Gilmour, & Mykitiuk, 2006; Oliver, 1990b; Withers, 2012). Frazee, Gilmour and Mykitiuk (2006) note that a “perverse result” of the disability determination process is that an individual’s personal experience of ability “must be buried or she runs the risk of being disqualified for benefits despite her obvious need for assistance” (pp. 242-3). The authors conclude with recommendations for further exploration of strategies of active resistance to “the dominant and oppressive meanings assigned” to the status of persons with disabilities.

This study presents an empirical analysis of resistance to medical documentation in the accommodation process and examines how different interpretations and applications of the Code shape how organizational and institutional work gets done. These different applications affect how human rights get operationalized in different ways and hence give rise to different work experiences for persons with disabilities.

We present evidence of the benefits of interpreting and applying the Code from the principles of inclusive design. It is our hope that employers can incorporate accessibility into the design and operations of their organizations and negate the need for individual accommodation. When accommodations are required, we encourage employers to critically reflect on whether requests for accommodation must be supported by medical documentation, and if so what is the underlying rationale for it. Macfarlane (2021) argues that the medical documentation requirement is often influenced by the widespread belief that persons who claim disability are faking. This belief leads to the second-guessing of a person’s need for accommodation.

It is possible to provide accommodations without documentation as it is done for religious accommodations (see also MacFarlane, 2021). Under the OHRC Policy on preventing discrimination based on creed (2015), employers have “a legal duty to accommodate people’s sincerely held creed beliefs and practices…Sincerity of belief should generally be accepted in good faith [and] it is inappropriate to require expert opinions to show that a [creed] practice or belief is mandatory or required or that it is sincerely held.”

It is important to note that many disability support programs that provide income replacement when a worker is off work due to injury or illness require medical documents (Torjman & Makhoul, 2016). This is beyond the control of organizations, but internal processes can still focus on the social and human rights models as the policy and practice approach whenever possible.

Future research could adapt the approach used in this study with consideration of other types of workplace accommodations for employees from various social locations to further examine the challenges and opportunities for everyday resistance in workplaces. Future research could also offer comparative analyses of different workplaces that resist the use of medical documentation to examine the impacts and influences of organizational size, sector and industry on the accommodation process and operational performance. The work performed by employees at nonprofit organizations is often very different from other industries and sectors. Thus, future research could consider how the accommodation process at Organization A and B could be incorporated in other organizations depending on the type of accommodation being requested and work being performed. Moreover, while this study analyzes the application of the human rights model of disability through an implied recognition of the intersectionality of disability, future research might narrow the focus to specific groups of persons, including persons with specific ethno-racial and/or gender identities.

Additionally, further examination of readings of other relevant laws and regulatory frameworks may be explored in future research to illuminate other forms of resistance to the medical model of disability. “As a practical matter, reading practices can be explored as procedures intrinsic to organization and decision making, opening them to intervention and change” (Turner, 2014, p. 221). Future research could also focus on the inclusive design principle of the duty to accommodate to provide more guidance for inclusive employment and eliminate use of medical documentation altogether.

Human rights law and policy can be used both as a tool to advance inclusive employment and to question and exclude the experiences of employees with disabilities. These opposing purposes present employers with a choice about how to accommodate and include employees with disabilities in the workplace. Realization of human rights in practice presents opportunities for the NPSS to disrupt ableism, advance inclusion and pay critical attention to issues of policy, power and inequality. Likewise, an organization’s model of work can either question or reinforce the medical model in which the knowledge of medical experts and health professionals are positioned as superior while disability is questioned and critiqued. Prioritizing subjective experiences of disability in workplace accommodations offers opportunity to re-present the profession’s role in the criticality of this social, political and economic issue.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article is to be meaningful and helpful to organizations and employees who want to operationalize an accommodation process that is consistent with the intent of the social and human rights models of disability. There is a need for more knowledge about practices and experiences of persons seeking disability-related accommodations in the workplace. This article contributes to disability studies literature to share knowledge about strategies of resistance to the medical model embedded in accommodation policy of many organizations.

This article helps to fill a gap in empirical research on alternative approaches to workplace accommodations and how the use of medical documentation creates a culture of distrust, and barriers to inclusion and a sense of belonging. We offer an articulation of accommodation processes in which an employee’s representation that they are disabled establishes that they are disabled and allows them to have power and control over their accommodations. However, with the permitted use of medical documentation in the accommodation process, the medical model remains entrenched in disability legislation and the human rights view is minimized. Lessening or eliminating medical documentation requirements from OHRC policy and increasing focus on inclusive design will center employees’ own expertise and empower persons with disabilities to co-create solutions to inaccessibility in the workplace. This will also provide for more opportunity for persons with disabilities to educate employers about the lived experience of disability and transform work processes.

Endnotes

References

- Baines, D., Cunningham, I., Campey, J., & Shileds, J. (2014). Not profiting from precarity: The work of nonprofit service delivery and the creation of precariousness. Just Labour, 22, 74-93.

- Breward, K. (2016). Predictors of employer-sponsored disability accommodation requesting in the workplace. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 5(1), 1-41. doi:https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v5i1.248

- Buettgen, A., & Klassen, T. (2020). The Role of the Nonprofit Sector as a Site for Inclusive Employment. Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research, 11(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.29173/cjnser.2020v11n2a367

- Conference Board of Canada. (2012). Employers’ toolkit: Making Ontario workplaces accessible to people with disabilities. Retrieved from http://www.conferenceboard.ca/e-library/abstract.aspx?did=5258

- Degener, T. (2016). A human rights model of disability. In P. Blanck & E. Flynn (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Disability Law and Human Rights (pp. 31-49): Routledge.

- DeVault, M. L., & McCoy, L. (2006). Institutional ethnography: Using interviews to investigate ruling relations. In D. E. Smith (Ed.), Institutional ethnography as practice (pp. 15-44). Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Devlin, R., & Pothier, D. (2006). Introduction: Toward a critical theory of dis-citizenship. In D. Pothier & R. Devlin (Eds.), Critical disability theory: Essays in philosophy, politics and law (pp. 1-24). Vancouver, BC UBC Press.

- Dirks, K., & Ferrin, D. (2001). The role of trust in organisational settings. Organisation Science, 12(4), 450-467.

- Finkelstein, V. (1980). Attitudes and disabled people. New York: World Rehabilitation Fund.

- Frazee, C., Gilmour, J., & Mykitiuk, R. (2006). Now you see her now you don’t: How law shapes disabled women’s experiences of exposure, surveillance, and assessment in the clinical encounter. In D. Pothier & R. Devlin (Eds.), Critical disability theory: Essays in philosophy, policy, and law (pp. 223-247). Toronto: UBC Press.

- Gates, L. B. (2000). Workplace accommodation as a social process. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 10, 85-98.

- Hollingsworth, J. R. (2000). Doing institutional analysis: Implications for the study of innovations. Review of International Political Economy, 7(4), 595-644.

- International Labour Organization. Disability and work. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/disability-and-work/lang--en/index.htm

- Johansson, A., & Vinthagen, S. (2020). Conceptualizing 'Everyday Resistance': A Transdisciplinary Approach: Routledge.

- Krebs, E. (2019). Baccalaureates or burdens? Complicating "reasonable accommodations" for American college students with disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly, 39(3). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v39i3

- Macfarlane, K. (2021). Disability without documentation. Fordham Law Review, 60. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3781221

- Morris, S., Fawcett, G., Brisebois, L., & Hughes, J. (2018). A demographic, employment and income profile of Canadians with disabilities aged 15 years and over, 2017. Retrieved from Statistics Canada: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-654-x/89-654-x2018002-eng.pdf?st=VxFYMflT

- Nevala, N., Pehkonen, I., Koskela, I., Ruusuvuori, J., & Anttila, H. (2015). Workplace accommodation among persons with disabilities: A systematic review of its effectiveness and barriers or facilitators. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 25, 432-448.

- Oliver, M. (1990a). The individual and social models of disability. Paper presented at the Joint Workshop of the Living Options Group and the Research Unit of the Royal College of Physicians. http://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/files/library/Oliver-in-soc-dis.pdf

- Oliver, M. (1990b). The politics of disablement. London: MacMillan.

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2015). Policy on preventing discrimination based on creed. Retrieved from https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/policy-preventing-discrimination-based-creed

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2016). Policy on ableism and discrimination based on disability. Retrieved from http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/policy-ableism-and-discrimination-based-disability

- Padkapayeva, K., Posen, A., Yazdani, A., Buettgen, A., Mahood, Q., & Tompa, E. (2016). Workplace accommodations for persons with physical disabilities: evidence synthesis of the peer-reviewed literature. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1-17. doi:10.1080/09638288.2016.1224276

- Prince, M. (2014). Locating a window of opportunity in the social economy: Canadians with disabilities and labour market challenges. Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research, 5(1), 6-20.

- Prodinger, B., & Turner, S. M. (2013). Using institutional ethnography to explore how social policies infiltrate into daily life. Journal of Occupational Science, 20(4), 357-369. doi:10.1080/14427591.2013.808728

- Reychav, I., & Sharkie, R. (2010). Trust: an antecedent to employee extra‐role behaviour. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 11(2), 227-247. doi:10.1108/14691931011039697

- Saltes, N. (2020). Disability barriers in academia: An analysis of disability accommodation policies for faculty at Canadian universities. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 9(1), 53-90. doi:https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v9i1.596

- Sanford, J. A., & Milchus, K. (2006). Evidence-based practice in workplace accommodations. Work, 27, 329-332.

- Scott, J. (1985). Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance: Yale University Press.

- Shaw, J., Wickenden, M., Thompson, S., & Mader, P. (2022). Achieving disability inclusive employment – Are the current approaches deep enough? Journal of International Development, 34(5), 942-963. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3692

- Smith, D. E. (2005). Institutional ethnography: A sociology for people. Toronto: Alta-Mira Press.

- Statistics Canada. (2009). Satellite account of non-profit institutions and volunteering. Retrieved from Ottawa: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/nea/list/npiv

- Stone, D. (1984). The disabled state. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Torjman, S., & Makhoul, A. (2016). Disability supports and employment policy. Retrieved from Caledon Institute of Social Policy: http://www.caledoninst.org/Publications/PDF/1105ENG.pdf

- Turner, S. M. (2014). Reading practices in decision processes. In D. E. Smith & S. M. Turner (Eds.), Incorporating Texts into Institutional Ethnographies (pp. 197-224). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- UN General Assembly. (2007). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/45f973632.html

- Van Ymerman, J., & Lalande, L. (2015). Change work: Valuing decent work in the not-for-profit sector. Retrieved from http://theonn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Report_Changework_ONN-Mowat-TNC_Atkinson_2015-11-25.pdf

- Wilton, R. (2006). Working at the margins: Disabled people and the growth of precarious employment. In D. Pothier & R. Devlin (Eds.), Critical disability theory: Essays in philosophy, policy, and law (pp. 129-150). Toronto: UBC Press.

- Wilton, R., & Schuer, S. (2006). Towards socio-spatial inclusion? Disabled people, neoliberalism and the contemporary labour market. Area, 38(2), 186-195.

- Withers, A. J. (2012). Disability politics and theory. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Pub.